1 Quantum Mechanics As a Stimulus for American Theoretical Physics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report 2013.Pdf

ATOMIC HERITAGE FOUNDATION Preserving & Interpreting Manhattan Project History & Legacy preserving history ANNUAL REPORT 2013 WHY WE SHOULD PRESERVE THE MANHATTAN PROJECT “The factories and bombs that Manhattan Project scientists, engineers, and workers built were physical objects that depended for their operation on physics, chemistry, metallurgy, and other nat- ural sciences, but their social reality - their meaning, if you will - was human, social, political....We preserve what we value of the physical past because it specifically embodies our social past....When we lose parts of our physical past, we lose parts of our common social past as well.” “The new knowledge of nuclear energy has undoubtedly limited national sovereignty and scaled down the destructiveness of war. If that’s not a good enough reason to work for and contribute to the Manhattan Project’s historic preservation, what would be? It’s certainly good enough for me.” ~Richard Rhodes, “Why We Should Preserve the Manhattan Project,” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, May/June 2006 Photographs clockwise from top: J. Robert Oppenheimer, General Leslie R. Groves pinning an award on Enrico Fermi, Leona Woods Marshall, the Alpha Racetrack at the Y-12 Plant, and the Bethe House on Bathtub Row. Front cover: A Bruggeman Ranch property. Back cover: Bronze statues by Susanne Vertel of J. Robert Oppenheimer and General Leslie Groves at Los Alamos. Table of Contents BOARD MEMBERS & ADVISORY COMMITTEE........3 Cindy Kelly, Dorothy and Clay Per- Letter from the President..........................................4 -

Samuel Goudsmit

NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES SAMUEL ABRAHAM GOUDSMIT 1 9 0 2 — 1 9 7 8 A Biographical Memoir by BENJAMIN BEDERSON Any opinions expressed in this memoir are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Academy of Sciences. Biographical Memoir COPYRIGHT 2008 NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES WASHINGTON, D.C. Photograph courtesy Brookhaven National Laboratory. SAMUEL ABRAHAM GOUDSMIT July 11, 1902–December 4, 1978 BY BENJAMIN BEDERSON AM GOUDSMIT LED A CAREER that touched many aspects of S20th-century physics and its impact on society. He started his professional life in Holland during the earliest days of quantum mechanics as a student of Paul Ehrenfest. In 1925 together with his fellow graduate student George Uhlenbeck he postulated that in addition to mass and charge the electron possessed a further intrinsic property, internal angular mo- mentum, that is, spin. This inspiration furnished the missing link that explained the existence of multiple spectroscopic lines in atomic spectra, resulting in the final triumph of the then struggling birth of quantum mechanics. In 1927 he and Uhlenbeck together moved to the United States where they continued their physics careers until death. In a rough way Goudsmit’s career can be divided into several separate parts: first in Holland, strictly as a theorist, where he achieved very early success, and then at the University of Michigan, where he worked in the thriving field of preci- sion spectroscopy, concerning himself with the influence of nuclear magnetism on atomic spectra. In 1944 he became the scientific leader of the Alsos Mission, whose aim was to determine the progress Germans had made in the development of nuclear weapons during World War II. -

An Original Way of Teaching Geometrical Optics C. Even

Learning through experimenting: an original way of teaching geometrical optics C. Even1, C. Balland2 and V. Guillet3 1 Laboratoire de Physique des Solides, CNRS, Université Paris-Sud, Université Paris-Saclay, F-91405 Orsay, France 2 Sorbonne Universités, UPMC Université Paris 6, Université Paris Diderot, Sorbonne Paris Cite, CNRS-IN2P3, Laboratoire de Physique Nucléaire et des Hautes Energies (LPNHE), 4 place Jussieu, F-75252, Paris Cedex 5, France 3 Institut d’Astrophysique Spatiale, CNRS, Université Paris-Sud, Université Paris-Saclay, F- 91405 Orsay, France E-mail : [email protected] Abstract Over the past 10 years, we have developed at University Paris-Sud a first year course on geometrical optics centered on experimentation. In contrast with the traditional top-down learning structure usually applied at university, in which practical sessions are often a mere verification of the laws taught during preceding lectures, this course promotes “active learning” and focuses on experiments made by the students. Interaction among students and self questioning is strongly encouraged and practicing comes first, before any theoretical knowledge. Through a series of concrete examples, the present paper describes the philosophy underlying the teaching in this course. We demonstrate that not only geometrical optics can be taught through experiments, but also that it can serve as a useful introduction to experimental physics. Feedback over the last ten years shows that our approach succeeds in helping students to learn better and acquire motivation and autonomy. This approach can easily be applied to other fields of physics. Keywords : geometrical optics, experimental physics, active learning 1. Introduction Teaching geometrical optics to first year university students is somewhat challenging, as this field of physics often appears as one of the less appealing to students. -

Trinity Site July 16, 1945

Trinity Site July 16, 1945 "The effects could well be called unprecedented, magnificent, beauti ful, stupendous, and terrifying. No man-made phenomenon of such tremendous power had ever occurred before. The lighting effects beggared description. The whole country was lighted by a searing light with the intensity many times that of the midday sun." Brig. Gen. Thomas Farrell A national historic landmark on White Sands Missile Range -- www.wsmr.army.mil Radiation Basics Radiation comes from the nucJeus of the gamma ray. This is a type of electromag individual atoms. Simple atoms like oxygen netic radiation like visible light, radio waves are very stable. Its nucleus has eight protons and X-rays. They travel at the speed of light. and eight neutrons and holds together well. It takes at least an inch of lead or eight The nucJeus of a complex atom like inches of concrete to stop them. uranium is not as stable. Uranium has 92 Finally, neutrons are also emitted by protons and 146 neutrons in its core. These some radioactive substances. Neutrons are unstable atoms tend to break down into very penetrating but are not as common in more stable, simpler forms. When this nature. Neutrons have the capability of happens the atom emits subatomic particles striking the nucleus of another atom and and gamma rays. This is where the word changing a stable atom into an unstable, and "radiation" comes from -- the atom radiates therefore, radioactive one. Neutrons emitted particles and rays. in nuc!ear reactors are contained in the Health physicists are concerned with reactor vessel or shielding and cause the four emissions from the nucleus of these vessel walls to become radioactive. -

Character List

Character List - Bomb Use this chart to help you keep track of the hundreds of names of physicists, freedom fighters, government officials, and others involved in the making of the atomic bomb. Scientists Political/Military Leaders Spies Robert Oppenheimer - Winston Churchill -- Prime Klaus Fuchs - physicist in designed atomic bomb. He was Minister of England Manhattan Project who gave accused of spying. secrets to Russia Franklin D. Roosevelt -- Albert Einstein - convinced President of the United States Harry Gold - spy and Courier U.S. government that they for Russia KGB. Narrator of the needed to research fission. Harry Truman -- President of story the United States Enrico Fermi - created first Ruth Werner - Russian spy chain reaction Joseph Stalin -- dictator of the Tell Hall -- physicist in Soviet Union Igor Korchatov -- Russian Manhattan Project who gave physicist in charge of designing Adolf Hitler -- dictator of secrets to Russia bomb Germany Haakon Chevalier - friend who Werner Reisenberg -- Leslie Groves -- Military approached Oppenheimer about German physicist in charge of leader of the Manhattan Project spying for Russia. He was designing bomb watched by the FBI, but he was not charged. Otto Hahn -- German physicist who discovered fission Other scientists involved in the Manhattan Project: Aage Niels Bohr George Kistiakowsky Joseph W. Kennedy Richard Feynman Arthur C. Wahl Frank Oppenheimer Joseph Rotblat Robert Bacher Arthur H. Compton Hans Bethe Karl T. Compton Robert Serber Charles Critchfield Harold Agnew Kenneth Bainbridge Robert Wilson Charles Thomas Harold Urey Leo James Rainwater Rudolf Pelerls Crawford Greenewalt Harold DeWolf Smyth Leo Szilard Samuel K. Allison Cyril S. Smith Herbert L. Anderson Luis Alvarez Samuel Goudsmit Edward Norris Isidor I. -

Ginling College, the University of Michigan and the Barbour Scholarship

Ginling College, the University of Michigan and the Barbour Scholarship Rosalinda Xiong United World College of Southeast Asia Singapore, 528704 Abstract Ginling College (“Ginling”) was the first institution of higher learning in China to grant bachelor’s degrees to women. Located in Nanking (now Nanjing) and founded in 1915 by western missionaries, Ginling had already graduated nearly 1,000 women when it merged with the University of Nanking in 1951 to become National Ginling University. The University of Michigan (“Michigan”) has had a long history of exchange with Ginling. During Ginling’s first 36 years of operation, Michigan graduates and faculty taught Chinese women at Ginling, and Ginlingers furthered their studies at Michigan through the Barbour Scholarship. This paper highlights the connection between Ginling and Michigan by profiling some of the significant people and events that shaped this unique relationship. It begins by introducing six Michigan graduates and faculty who taught at Ginling. Next we look at the 21 Ginlingers who studied at Michigan through the Barbour Scholarship (including 8 Barbour Scholars from Ginling who were awarded doctorate degrees), and their status after returning to China. Finally, we consider the lives of prominent Chinese women scholars from Ginling who changed China, such as Dr. Wu Yi-fang, a member of Ginling’s first graduating class and, later, its second president; and Miss Wu Ching-yi, who witnessed the brutality of the Rape of Nanking and later worked with Miss Minnie Vautrin to help refugees in Ginling Refugee Camp. Between 2015 and 2017, Ginling College celebrates the centennial anniversary of its founding; and the University of Michigan marks both its bicentennial and the hundredth anniversary of the Barbour Gift, the source of the Barbour Scholarship. -

J. Robert Oppenheimer

Priscilla J. McMillan The Ruin of J. Robert Oppenheimer and the Birth of the Modern Arms Race VIKING VIKING Published by the Penguin Group Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 100I4, U.S.A. Penguin Group (Canada), 10 Alcorn Avenue, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4V 3B2 (a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.) Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R oRL, England Penguin Ireland, 25 St. Stephen's Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd) Penguin Books Australia Ltd, 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia (a division of Pearson Australia Group Pry Ltd) Penguin Books India Pvt Lrd, II Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi-no 0I7, India Penguin Group (NZ), Cnr Airborne and Rosedale Roads, Albany, Auckland 1310, New Zealand (a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd) Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pry) Ltd, 24 Srurdee Avenue, Rosebank, Johannesburg 2196, South Africa Penguin Books Lrd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R oRL, England First published in 2005 by Viking Penguin, a member of Penguin Group (USA) Inc. 7 9 10 8 6 4 2 Copyright © Priscilla Johnson McMillan, 2005 All rights reserved Photograph credits appear on page 374- LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA McMillan, Priscilla Johnson. The ruin of J. Robert Oppenheimer / Priscilla J. McMillan. p. ern. Includes index. ISBN 0-670-03422-3 I. Oppenheimer, J. Robert, 1904-1967. 2. Physicists-United States-Biography. 3. Manhattan Project (U.S.) 4- Atomic bomb-United States-s-History. 5. Nuclear physics- United States-Histoty-20th century. 6. Teller, Edward, 1908- I. -

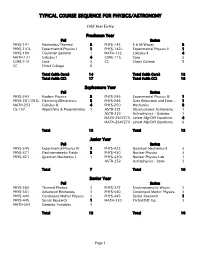

Typical Course Sequence for Physics/Astronomy

TYPICAL COURSE SEQUENCE FOR PHYSICS/ASTRONOMY Odd Year Entry Freshman Year Fall Spring PHYS-141 Mechanics/Thermal 3 PHYS-142 E & M/Waves 3 PHYS-141L Experimental Physics I 1 PHYS-142L Experimental Physics II 1 PHYS-190 Freshman Seminar 1 MATH-132 Calculus II 4 MATH-131 Calculus I 4 CORE-115 Core 5 CORE-110 Core 5 CC Christ College 8 CC Christ College 8 Total (with Core) 14 Total (with Core) 13 Total (with CC) 17 Total (with CC) 16 Sophomore Year Fall Spring PHYS-243 Modern Physics 3 PHYS-245 Experimental Physics III 1 PHYS-281/281L Electricity/Electronics 3 PHYS-246 Data Reduction and Error... 1 MATH-253 Calculus III 4 PHYS-250 Mechanics 3 CS-157 Algorithms & Programming 3 ASTR-221 Observational Astronomy 1 ASTR-253 Astrophysics - Galaxies 3 MATH-260/270 Linear Alg/Diff Equations 4 MATH-264/270 Linear Alg/Diff Equations 6 Total 13 Total 13 Junior Year Fall Spring PHYS-345 Experimental Physics IV 1 PHYS-422 Quantum Mechanics II 3 PHYS-371 Electromagnetic Fields 3 PHYS-430 Nuclear Physics 3 PHYS-421 Quantum Mechanics I 3 PHYS-430L Nuclear Physics Lab 1 ASTR-252 Astrophysics - Stars 3 Total 7 Total 10 Senior Year Fall Spring PHYS-360 Thermal Physics 3 PHYS-372 Electromagnetic Waves 3 PHYS-381 Advanced Mechanics 3 PHYS-440 Condensed Matter Physics 3 PHYS-440 Condensed Matter Physics 3 PHYS-445 Senior Research 1 PHYS-445 Senior Research 1 MATH-330 Partial Diff. Eq. 3 MATH-334 Complex Variables 3 Total 13 Total 10 Page 1 TYPICAL COURSE SEQUENCE FOR PHYSICS/ASTRONOMY Even Year Entry Freshman Year Fall Spring PHYS-141 Mechanics/Thermal 3 PHYS-142 E & M/Waves 3 PHYS-141L Experimental Physics I 1 PHYS-142L Experimental Physics II 1 PHYS-190 Freshman Seminar 1 MATH-132 Calculus II 4 MATH-131 Calculus I 4 CORE-115 Core 5 CORE-110 Core 5 CC Christ College 8 CC Christ College 8 Total (with Core) 14 Total (with Core) 13 Total (with CC) 17 Total (with CC) 16 Sophomore Year Fall Spring PHYS-243 Modern Physics 3 PHYS-245 Experimental Physics III 1 PHYS-281 Electricity/Electronics 3 PHYS-250 Mechanics 3 MATH-253 Calculus III 4 PHYS-246 Data Reduction and Error.. -

Physics, M.S. 1

Physics, M.S. 1 PHYSICS, M.S. DEPARTMENT OVERVIEW The Department of Physics has a strong tradition of graduate study and research in astrophysics; atomic, molecular, and optical physics; condensed matter physics; high energy and particle physics; plasma physics; quantum computing; and string theory. There are many facilities for carrying out world-class research (https://www.physics.wisc.edu/ research/areas/). We have a large professional staff: 45 full-time faculty (https://www.physics.wisc.edu/people/staff/) members, affiliated faculty members holding joint appointments with other departments, scientists, senior scientists, and postdocs. There are over 175 graduate students in the department who come from many countries around the world. More complete information on the graduate program, the faculty, and research groups is available at the department website (http:// www.physics.wisc.edu). Research specialties include: THEORETICAL PHYSICS Astrophysics; atomic, molecular, and optical physics; condensed matter physics; cosmology; elementary particle physics; nuclear physics; phenomenology; plasmas and fusion; quantum computing; statistical and thermal physics; string theory. EXPERIMENTAL PHYSICS Astrophysics; atomic, molecular, and optical physics; biophysics; condensed matter physics; cosmology; elementary particle physics; neutrino physics; experimental studies of superconductors; medical physics; nuclear physics; plasma physics; quantum computing; spectroscopy. M.S. DEGREES The department offers the master science degree in physics, with two named options: Research and Quantum Computing. The M.S. Physics-Research option (http://guide.wisc.edu/graduate/physics/ physics-ms/physics-research-ms/) is non-admitting, meaning it is only available to students pursuing their Ph.D. The M.S. Physics-Quantum Computing option (http://guide.wisc.edu/graduate/physics/physics-ms/ physics-quantum-computing-ms/) (MSPQC Program) is a professional master's program in an accelerated format designed to be completed in one calendar year.. -

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: the PRINCIPAL UNCERTAINTY: U.S

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: THE PRINCIPAL UNCERTAINTY: U.S. ATOMIC INTELLIGENCE, 1942-1949 Vincent Jonathan Houghton, Doctor of Philosophy, 2013 Dissertation directed by: Professor Jon T. Sumida Department of History The subject of this dissertation is the U. S. atomic intelligence effort against both Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union in the period 1942-1949. Both of these intelligence efforts operated within the framework of an entirely new field of intelligence: scientific intelligence. Because of the atomic bomb, for the first time in history a nation’s scientific resources – the abilities of its scientists, the state of its research institutions and laboratories, its scientific educational system – became a key consideration in assessing a potential national security threat. Considering how successfully the United States conducted the atomic intelligence effort against the Germans in the Second World War, why was the United States Government unable to create an effective atomic intelligence apparatus to monitor Soviet scientific and nuclear capabilities? Put another way, why did the effort against the Soviet Union fail so badly, so completely, in all potential metrics – collection, analysis, and dissemination? In addition, did the general assessment of German and Soviet science lead to particular assumptions about their abilities to produce nuclear weapons? How did this assessment affect American presuppositions regarding the German and Soviet strategic threats? Despite extensive historical work on atomic intelligence, the current historiography has not adequately addressed these questions. THE PRINCIPAL UNCERTAINTY: U.S. ATOMIC INTELLIGENCE, 1942-1949 By Vincent Jonathan Houghton Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Maryland, College Park, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2013 Advisory Committee: Professor Jon T. -

Making the Bomb by John Lamperti

November, 2012 Thoughts on Making the Bomb by John Lamperti I recently finished reading Martin Sherwin and Kai Bird’s monumental American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer.1 It's an admirable book, although I think the title might better have been American Faust. (No less than Freeman Dyson said Oppenheimer made a "Faustian bargain."2) There have been many books about Oppenheimer and the atomic bomb project in general; I've read some but not all of them. This one seems to be definitive. Everything we need to know is there – and it's a fascinating read. Two things struck me especially, and neither was directly about Oppenheimer. One was the ideological rigidity, and the blindness, of the crowd of Army and FBI "security" operatives who dogged Oppenheimer and the whole Manhattan Project from the beginning. To a man (no women are mentioned) they were obsessed with the pre-war leftist politics of many of the scientists, which they found highly suspicious and probably indicative of disloyalty. But while these agents were hounding leftists and "premature anti-fascists" (as supporters of the Spanish Republic were called) at Los Alamos and elsewhere and finding little or nothing, real spies were sending real scientific information to the USSR under their noses, apparently unsuspected. If the "security" people, especially Lt. Col. Boris Pash of Army Counter– Intelligence, had been given free rein, Oppenheimer and many others (but not the actual spies!) would have been banished from the Project and the "Trinity" test, as well as the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, might never have happened. -

Experimental Physics I PHYS 3250/3251

Syllabus Experimental Physics I PHYS 3250/3251 Course Description: Introduction to experimental modern physics, measurement of fundamental constants, repetition of crucial experiments of modern physics (Stern Gerlach, Zeeman effect, photoelectric effect, etc.) Course Objectives: The objective of this course is introduce you to the proper methods for conducting controlled physics experiments, including the acquisition, analysis and physical interpretation of data. The course involves experiments which illustrate the principles of modern physics, e.g. the quantum nature of charge and energy, etc. Succinct, journal-style reports will be the primary output for each experiment, with at least one additional presentation (oral and/or poster) required. Text: An Introduction to Error Analysis, 2nd Edition, J.R. Taylor, ISBN 0-935702-75-X. Additional documentation for any assigned experiments will be supplied as needed. Learning Outcomes: At the conclusion of this course, students will be able to: 1) Assemble and document a relevant bibliography for a physics experiment. 2) Prepare a journal-style manuscript using scientific typesetting software. 3) Plan and conduct experimental measurements in physics while employing proper note-taking methods. 4) Calculate uncertainties for physical quantities derived from experimental measurements. Clemson Thinks2: What is Critical Thinking? This course is designed to be part of the Clemson Thinks2 (CT2) program. “Critical thinking is reasoned and reflective judgment applied to solving problems or making decisions about what to believe or what to do. Critical thinking gives reasoned consideration to defining and analyzing problems, identifying and evaluating options, inferring likely outcomes and probable consequences, and explaining the reasons, evidence, methods and standards used in making those analyses, inferences and evaluations.