Grassroots Participatory Budgeting Process in Negros Province

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Negros Occidental Calinog ! Passi City San Passi Y DSWD N U DSWD City Sa Rafael J Bantayan Ue a DSWD La Nriq Barotac Mbunao E DSWD Viejo

MA045_v5_Negros Occidental Calinog ! Passi City San Passi y DSWD n u DSWD City Sa Rafael j Bantayan ue A DSWD La nriq Barotac mbunao E DSWD Viejo a D ue B m n a a n a s r DSWD a r DSWD BUCC, Oxfam, DSWD te CARE, DSWD, e DSWD d Sam's l o N GOAL, a e ° A N TI QU E Ba l la V 1 Jan dia g i Purse 1 i n DSWD n ua ga in SCI, WFP y n A D DSWD DSWD, Cadiz o DSWD i DSWD DSWD DSWD City g n i DSWD GOAL, WVI ! P a a l m o tac S aro p e M B a a t a DSWD o s a i n R n o i t uev N n a DSWD M n DSWD, WVI E Victorias a n M DSWD n riq ! ILO IL O a M u V A u a e t N ga B ic li e . t z m a w lo o i b n o L C r d y u Z a i DSWD d a ce DSWD a t y na it a i i a y s a a C n C g r C a DSWD r S ty a angas DSWD i g Dum C T Le ta a te u o an a DSWD, n b n DSWD S ar la u rb DSWD Silay a n a s DSWD HelpAge c ity g B ane ! s a San eg DSWD E C n L DSWD el ia Si Migu v lay a Ci DSWD P ty DSWD DSWD s o l i y DSWD Talisay a n t r G Oto o i DSWD l ! I a u C Tob b i Tigba os m uan T DSWD o g B a I u lis b Iloilo ! en ay a a Cit l City vi Bacolod y o s ta a ! g DSWD Bac DSWD a o i lo DSWD City d DSWD M C NE GR OS alat DSWD DSWD rava DSWD DSWD DSWD OC CI D EN TA L L o ia S an r c e ord a r n u J n Salvador z M o Benedicto Bago S Pulupandan City DSWD ib DSWD u ! Asturias n DSWD B a ago g DSWD DSWD City DSWD DSWD DSWD V San DSWD a Balamban V N ll arlos a u DSWD ad C le e o v l City n a id c ia La C arlota DSWD City DSWD DSWD Canlaon Toledo CIty City DSWD V ! ! C a a na l o a l a ll C n Pontevedr aste e d C l e La i a h l y t t y e o i DSWD o T DSWD n r C m o s o P in Naga M am -

CSHP) DOLE-Regional Office No

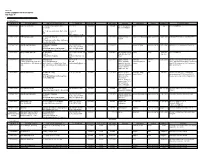

REGIONAL REPORT ON THE APPROVED/CONCURRED CONSTRUCTION SAFETY & HEALTH PROGRAM (CSHP) DOLE-Regional Office No. 6 August 2018 Date No. Project Owner/General Contractor Project Name and Location Remarks Approved 18GF0081 REHABILITATION/WIDENING OF MUNICIPAL ROAD, DPWH Iloilo 1st DEO/EDISON DEV'T. & August 10, 1 POBLACION, TIGBAUAN, ILOILO ALLERA ST. AND TOLOSA Concurred CONSTRUCTION 2018 ST. TIGBAUAN, ILOILO DPWH Iloilo 1st DEO/EDISON DEV'T. & 18GF0083 CONSTRUCTION OF ROAD SLOPE PROTECTION August 10 , 2 Concurred CONSTRUCTION STRUCTURE-ILOILO-ANTIQUE-ROAD (K0069+020-K0069+049) 2018 18GJ0144 CONSTRUCTION OF SCHOOL BUILDINGS IN THE DPWH Iloilo DEO/A.D. PENDON August 8, 3 ELEMENTARY CLASSROOMS M.N HECHANOVA MES, Concurred CONSTRUCTION & SUPPLY, INC. 2018 2STY10CL 18GI0098 REHABILITATION/REPAIR OF SLOE PROTECTION DPWH Iloilo 4th DEO/C'ZARLES OF ILOILO FLOOD CONTROL PROJECT INCLUDING August 1, 4 Concurred CONSTRUCTION AND SUPPLY IMPROVEMENT OF SERVICE ROAD ALONG AGANAN AND 2018 TIGUM RIVERS 18GJ0148- CONSTRUCTION OF SCHOOL BUILDINGS IN THE DPWH Iloilo DEO/VN GRANDE BUILDERS & August 2, 5 ELEMENTARY CLASSROOMS BUNTATALA TAGBAC Concurred SUPPLY 2018 ELEMENTARY SCHOOL, 2STY4CL 18GI0097 REHAABILITATION/REPAIR OF SLOPE DPWH Iloilo 4th DEO/A.D. PENDON August 2, 6 PROTECTION OF ILOILO FLOOD CONTROL PROJECT AT Concurred CONSTRUCTION & SUPPLY, INC. 2018 TIGUM RIVER DPWH Iloilo 1st DEO/PITONG BUILDERS & 18GF0088 REPAIR/MAINTENANCE OF BULUANGAN RIVER August 3, 7 Concurred CONSTRUCTION SUPPLY SSPURDIKE 2 ALONG BULUANGAN RIVER, GUIMBAL,ILOILO 2018 DPWH Iloilo 1st DEO/PITONG BUILDERS & 18GF0101 REPAIR/MAINTENANCE OF JARAO RIVER August 3, 8 Concurred CONSTRUCTION SUPPLY SPURDIKE 9 ALONG JARAO,GUIMBAL,ILOILO 2018 DPWH Iloilo 1st DEO/PITONG BUILDERS & 18GF0087 REPAIR/MAINTENANCE OF BULUANGAN RIVER August 3, 9 Concurred CONSTRUCTION SUPPLY SPURDIKE 1 ALONG BULUANGAN RIVER, GUIMBAl,ILOILO 2018 DPWH Iloilo DEO/G.F. -

Candoni-Gatuslao-Basay Bdry Road, Negros Occidental

Republic of the Philippines DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC WORKS AND HIGWAYS REGIONAL OFFICE VI Fort San Pedro, Iloilo City INVITATION TO BID For Contract ID No.: 21G00048 Contract Name: Candoni-Gatuslao-Basay Bdry Road, Negros Occidental 1. The Department of Public Works and Highways Regional Office VI through the FY 2021 GAA intends to apply the sum of Php 101,325,000.00 being the Approved Budget for the Contract (ABC) to payments under the contract for Contract ID No. 21G00048 – Candoni-Gatuslao-Basay Bdry Road, Negros Occidental. Bids received in the excess of the ABC shall be automatically rejected at bid opening. 2. The Department of Public Works and Highways Regional Office VI through its Bids and Awards Committee now invites bids for the hereunder Works: Name of Contract : Candoni-Gatuslao-Basay Bdry Road, Negros Occidental Contract ID No. : 21G00048 Locations : Candoni, Hinoba-an, Negros Occidental Scope of Works : Construction of Concrete Road Approved Budget Php 101,325,000.00 : for the Contract Contract Duration : 319 calendar days 3. Prospective Bidders should be (1) registered with and classified by the Philippine Contractors Accreditation Board (PCAB) with PCAB LICENSE Category of B for Medium A The description of an eligible Bidder is contained in the Bidding Documents, particularly, in Annex II-1 B Section II and III of Bidding Documents. Contractors/applicants who wish to participate in this bidding are encourage to enroll in the DPWH Civil Works Application (CWA) at the DPWH Procurement Service (PrS), 5th Floor, DPWH Bldg., Bonifacio Drive, Port Area, Manila, while those already enrolled shall keep their records current and updated. -

Socio-Economic Benefits and Constraints for Mussel Farming Industry in Southern Negros Occidental Philippines

p-ISSN 2094-4454 RESEARCH ARTICLE Socio-economic Benefits and Constraints for Mussel Farming Industry in Southern Negros Occidental Philippines Andrew D. Ordonio, Aniceto D. Olmedo, Mac Edmund G. Gimotea, Jovelle B. Vergara, Mark Ian R. Toledo, Carlos Hilado Memorial State College College of Fisheries Enclaro, Binalbagan, Negros Occidental Philippines Abstract: This study aims at understanding the socio-economic benefits accrued to mussel farmers and the constraints that hindrance the development of mussel farming in southern Negros Occidental province Philippines. Using a semi-structured open-ended one-on-one questionnaire, primary data were collected from a sample of 23 randomly selected mussel farming households in three farming areas in southern Negros Occidental province. The farmers considered mussel farming as alternative/supplemental livelihood to fishing. Currently, the investment for mussel farming is categorized as small-scale and family-based. Mussel farming helped augment family’s income. From the income they derive from mussel farming, they can now buy the basic needs of their families and they can even pay promptly their accounts from local credits. They further noted they can afford now to buy electronic gadgets and other appliances as well as spend some of their earnings for house repairs. Although, the benefits derived from mussel farming is positive, somehow, the farmers were impeded by constraints that hindrance the development of mussel farming industry. They had in mind that the lack of knowledge and Extension support probably hindrance the development of the mussel farming. If they are organized as community, they might as well can participate to any Extension activities designed for them. -

GRAVITY 1. Bago RIS La Carlota City 4TH District 0 357.00 0.00 0.00 2

PROVINCE / MUNICIPALITY DISTRICT NO OF SYSTEM SERVICE AREA CONVERTED PERMANENTLY CATEGORY / AREAS NON- DIVERSION / RESTORABLE SYSTEMS NEGROS NATIONALOCCIDENTAL GIRRIGATION - GRAVITY 1. Bago RIS La Carlota City 4TH District 0 357.00 0.00 0.00 2. Bago RIS Murcia 3RD District 0 258.50 0.00 0.00 3. Bago RIS Pulupandan 4TH District 0 178.60 16.78 0.00 4. Bago RIS Valladolid 4TH District 0 2,914.00 295.17 0.00 5. Bago RIS San Enrique 4TH District 0 652.00 139.53 0.00 6. Bago RIS Bago City 4TH District 0 8,315.40 294.52 0.00 7. Bago RIS Bacolod City Lone District 1 25.00 0.00 0.00 8. Hilabangan Kabankalan 6TH District 0 0.00 0.00 0.00 River Irrigation City, Ilog & Project Himamaylan City 9. Pangiplan Himamaylan 5TH District 0 757.00 0.00 255.30 RIS City 10. Pangiplan Binalbagan 5TH District 1 1,083.00 100.00 316.70 G - GRAVITY 2 14,540.50 846.00 572.00 NATIONAL 2 14,540.50 846.00 572.00 IRRIGATION 1,418.00 Bacolod City 25.00 0.00 0.00 Bago 8,315.40 294.52 0.00 Binalbagan 1,083.00 100.00 316.70 Himamaylan City 757.00 0.00 255.30 Kabankalan City, Ilog & Himamaylan City La Carlota City 357.00 0.00 0.00 Murcia 258.50 0.00 0.00 Pulupandan 178.60 16.78 0.00 San Enrique 652.00 139.53 0.00 Valladolid 2,914.00 295.17 0.00 TOTAL 14,540.50 846.00 572.00 PROVINCE / MUNICIPALITY DISTRICT NO OF SERVICE CONVERTED PERMANENTL CATEGORY / SYSTEM AREA AREAS Y NON- DIVERSION / RESTORABLE SYSTEMS COMMUNAL IRRIGATION SYSTEM G - GRAVITY 1. -

List Or Participants

Institute for Global Environmental Strategies (IGES), United Nations Economic Commission for Asia and the Pacific (UNESCAP), the Provincial Government of Negros Occidental, and the City Government of Bago The Kitakyushu Initiative National Conference on Solid Waste Management: Bridging the Gap Between Policy and Local Actions Talisay City, Philippines 28 & 29 May 2009 LIST OF PARTICIPANTS Local Government Units, Philippines Bacolod City Mr.Raymund Sacudit, Jr., Bacolod City, Negros Occidental, Philippines Binalbagan Municipality Ms.Pearle Pagunsan, Medical Officer V, Binalbagan City, Negros Occidental, Philippines Calatrava Municipality Mr. Edwin Aburido OIC‐SWMP, Calatrava Municipal Government, Calatrava Municipality, Negros Occidental, Philippines Mr.Reynith Caballero, MPDO – Staff, , Calatrava Municipal Government, Calatrava Municipality, Negros Occidental, Philippines Mr. Ernesto Ponsica, MPDC, , Calatrava Municipal Government, Calatrava Municipality, Negros Occidental, Philippines Cebu City Mr. Nigel Paul Villarete, City Planning and Development Coordinator, Cebu City, Philippines EB Magalona Municipality Mr. Noel Resuma, EMS II, Municipal Government of EB Magalona, EB Magalona Municipality, Negros Occidental, Philippines Hinigaran Municipality Mr. Ernesto Mohametano, SB Member, Municipal Government of Hinigaran, Hinigaran Municipality, Negros Occidental, Philippines Isabela Municipality Ms.Maria Rama Espinosa, MHO, Municipal Government of Isabela, Isabela Municipality, Negros Occidental, Philippines Ms.Salvacion de la Cruz, Municipal -

Economic Analysis of Milkfish Aquaculture in Southern Negros Occidental, Philippines

p-ISSN 2094-4454 RESEARCH ARTICLE Economic Analysis of Milkfish Aquaculture in Southern Negros Occidental, Philippines Geofrey A. Rivera Faculty, College of Business Administration CHMSC Binalbagan Campus Abstract: Given the economic profitability of Milkfish in the 5th District of Negros Occidental, this study on economic analysis of milkfish aquaculture using financial performance; sensitivity analysis; and coping strategies to ascertain sustainability and production, conducted. Information on the profile of the respondents, problems they met and adaptive coping strategies, and other pertinent financial data needed were elicited from the three areas such as Himamaylan, Binalbagan, and Hinigaran using the researcher–made questionnaire. Financial performance was computed and analyzed and subjected to statistical analysis. Results showed that extensive aquaculture production system gained significantly highest return on investment (ROI) for about .34 and significantly lowest in payback period (PBP) for 2.92 production period; while, intensive production system gained the significantly lowest return on investment of .24 and significantly highest in payback period for 4.30 production period; and semi-intensive aquaculture production system gained a .28 ROI, lower than extensive but higher than intensive systems. In terms of PBP which was 3.58 production period, it was higher than extensive, but lower than intensive. The significant positive relationship on the financial performance signifies the positive effect of the variables on the capitalization of the milkfish growers. On the five stated problems met, most of them was environmental problem which was handled using adapted strategies, while the fluctuating change in the fish farm gate price, variable cost, fixed cost that affects milkfish production and sales was manageable. -

Grassroots Participatory Budgeting Process in Negros Province Fatima Lourdes Del Prado, Gabriel Antonio Florendo and Maureen Ane Rosellon DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES NO

Philippine Institute for Development Studies Surian sa mga Pag-aaral Pangkaunlaran ng Pilipinas Grassroots Participatory Budgeting Process in Negros Province Fatima Lourdes del Prado, Gabriel Antonio Florendo and Maureen Ane Rosellon DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES NO. 2015-28 The PIDS Discussion Paper Series constitutes studies that are preliminary and subject to further revisions. They are be- ing circulated in a limited number of cop- ies only for purposes of soliciting com- ments and suggestions for further refine- ments. The studies under the Series are unedited and unreviewed. The views and opinions expressed are those of the author(s) and do not neces- sarily reflect those of the Institute. Not for quotation without permission from the author(s) and the Institute. April 2015 For comments, suggestions or further inquiries please contact: The Research Information Staff, Philippine Institute for Development Studies 5th Floor, NEDA sa Makati Building, 106 Amorsolo Street, Legaspi Village, Makati City, Philippines Tel Nos: (63-2) 8942584 and 8935705; Fax No: (63-2) 8939589; E-mail: [email protected] Or visit our website at http://www.pids.gov.ph Grassroots Participatory Budgeting Process in Negros Province Fatima Lourdes Del Prado, Gabriel Antonio Florendo and Maureen Ane Rosellon Abstract This paper is a narrative account and assessment of the Grassroots Participatory Budgeting (GPB) process in three municipalities of the Negros Province, namely, Sagay City, Hinigaran and Cauayan. The GPB process was implemented with the objective of -

Negros Occidental Calinog ! Passi Passi an City S E Y City Qu San Ju Bantayan Nri C a Lamb E Rafael Ota Unao Bar

MA047_v1_Negros Occidental Calinog ! Passi Passi an City S e y City qu San ju Bantayan nri c A Lamb E Rafael ota unao Bar a jo Du Vie m en a as B r a r n e a ILO, Oxfam d t l le e a g o V N n i la ° J i DOLE, 1 a D ni Ba n 1 uay dia ngan A ILO A N TI QU E Cadiz o P i City g o ! n i t a DOLE, o a l m t S a p e ILO IL O a M n ILO a i n c a R asi Barota y n n a M g n uevo a a y a N ! S it V M u Victorias C t N E ic A a ew nr to li b M iq C r m a Luc u ia o ena ag e ity s Z B d C a z lo . i ia a n n a d y r t a i a r t a s n nga C C a a g a S r Dum te a a T L rb n u e a la b o B a u n Silay c ty n nes ! s i g San ega Si E C a L lay n Miguel ia C v ity s a a P r a Talisay b o ! l g i I y Oton t DOLE, ILO T o i ob G l os Ti I B T DOLE o gbauan C a u ue lis i ! ay m n C av ity b Iloilo is Bacolod o a ta ! a l City g Bac a o i lo C d M ity Cala trav S L a o n a a ia d r or n J e c r n u z Salvador M o Benedic Bago to S City Asturias ib u ! B n ago a Pulupandan g City V N n Balamban a u V Sa le e a v lla arlos n a d C c o i ity a lid C La C arlota C ity Canlaon Toledo City CIty V ! ! C a a l l e C n o l h d dra i a teve e e Pon t l y a y o t llan r o i ste n m T La Ca C o s NE GR OS o P Mo in H OC CI D EN TA L ise am in Pa s u iga di n ra lla ga n h a y g a t n i a C N Isabela n A a log g u F S n in e a l y s n t a rn u i n a h n i C d u o G B i C ina il a lba r rc gan a ar B H i La m Li am ber C a tad it yl D y an um an jug S ibong Kabankalan Jim a N a R ° la o 0 City lud nd 1 ! a T ay as Alcantara an C EB U Mo alb oal o n a la g Cauayan a r -

Annex "B" Mining Tenements Statistics Report I. Mineral

ANNEX "B" MINING TENEMENTS STATISTICS REPORT MGB-Region VI I. MINERAL PRODUCTION SHARING AGREEMENTS B. Under Process TENEMENT ID TENEMENT HOLDER CONTACT PERSON/ADDRESS TELEPHONE NO. DATE FILED AREA (has.) Barangay Municipality Province COMMODITY STATUS/REMARKS APSA-000022 Regina Lacson-Santos #20 Waling-Waling, Capitolville Subd., (034) 20808 7/14/1994 399.0249 Bito-on, Barangcalan, Carles Iloilo clay Indorsed to MGB-CO Bacolod City Batuanan & Tinigban or 1 No. 11, Greenmeadows Subd., Quezon City, (02) 6330231 M.M. email: [email protected] APSA-000032 BF Mining Corporation Mr. Teodoro G. Bernardo Tel. Nos. 816-7161 to 72 12/1/2094 4,722.5968 Cartagena, Bulata, Cauayan and Sipalay City Negros Occidental copper, gold, pending NCIP/ with adverse claim filed at PA President Inayauan 2 4/F Manila Memorial Park Bldg. 2283 Pasong Tamo Ext., Makati City APSA-000064 Philex Mining Corporation Mr. Manuel V. Pangilinan (632) 631-13-81 to 88 9/29/1995 1,512.6255 Cauayan & Sipalay Negros Occidental gold, copper pending NCIP/ with adverse claim filed at PA Chairman Fax No. (632) 631-94-94 3 Mr. Eulalio B. Austin - Pres. and CEO Email: [email protected] Philex Building, No. 27 Brixton St., Pasig City APSA-000065 Quarry Ventures Phils.,Inc. Ms. Ester Rosca (02) 631-9123 to 27 and 632- 10/2/1995 2,292.6400 Luhod Bayang, Duyong, Pandan Antique marbleized Indorsed to MGB-CO President 7622 Tingib, Mab-aba & Sto. limestone 4 117 Shaw Blvd., Pasig City Fax No. 633-5249 and 634- Rosario 3342 APSA-000067 Suntria Corporation Arnold B. Caoili (632) 661-8171 10/2/1995 7,964.4306 Agpipili, Alcantara, Lemery and Iloilo and gold, copper Indorsed to MGB-CO per memorandum dated (Formerly: Coresources Mining Dev't. -

AB 0243 L Site Suitability Analysis for Aquaculture Features Along

IMPROVING RIVER NAVIGATION SYSTEMS WHILE PRESERVING OYSTER FARMS: A SITE SUITABILITY ANALYSIS FOR AQUACULTURE FEATURES ALONG HINIGARAN RIVER Mark Anthony A. Cabanlit1, Judith R. Silapan2, Brisneve Edullantes2, Ariadne Victoria S. Pada1, Julius Jason S. Garcia1, Roxanne Marie S. Albon1, Rembrandt Cenit1, John Jaasiel S. Juanich1, Wilfredo C. Mangaporo1, Jerard Vincent M. Leyva1, Deo Jan D. Regalado1 1University of the Philippines Cebu Phil-LiDAR 2, Cebu City, Cebu, Philippines, Email: [email protected] 2University of the Philippines Cebu, Cebu City, Cebu, Philippines, Email: [email protected] KEY WORDS: LiDAR, Aquaculture, Fisheries, Coastal Resource ABSTRACT: Rivers may be used for both navigation and aquaculture. With this twin yet conflicting services provided by the river, a science-based management approach is necessary in order to protect and regulate the river’s use. The Hinigaran River of Negros Occidental Western Philippines is home to various aquaculture facilities, ranging from very large fish pens to small structures such as oyster culture-stakes. The main objective of this study was to delineate the suitable area for aquaculture along the river and identify the optimal navigation route without jeopardizing culture operations. Through weighted overlay, the following were used in the suitability analysis: vulnerability to flooding, land suitability, vulnerability to erosion, land cover, slope classification, type of soil, rain induced landslide, strategic agricultural and fisheries development zone, and tsunami vulnerability. The section of the river that has been identified as suitable based on the weighted overlay, was then added with an inward buffer that was classified as candidate sites for oyster culture. These candidate sites were then further classified as to whether it was not suitable or suitable for oyster culture. -

Risk Assessment and Mapping for Canlaon Volcano, Philippines

RISK ASSESSMENT AND MAPPING FOR CANLAON VOLCANO, PHILIPPINES Rowena B. Quiambao Philippine Institute of Volcanology and Seismology (PHIVOLCS), C. P. Garcia Street, University of the Philippines Campus, Diliman, Quezon City, PHILIPPINES 1101 - [email protected] KEY WORDS: Hazards, Risk, Mapping, Volcanoes, Disaster, GIS, Spatial, Method ABSTRACT: Risk assessment and mapping for Canlaon Volcano, Philippines is reported in this paper. Volcanic hazards in Canlaon Volcano affect the lives and properties within the vicinity. Thus, risk is present as a result of the relationship between the hazards and the human and non-human elements. The volcanic hazards considered were pyroclastic flow, lava flow and lahar. The risk of these hazards to two main factors was investigated, namely, to lives and to infrastructure and/or utility. Using the risk equation from the United Nations International Strategy for Disaster Reduction (Risk = Hazard x Vulnerability), actual computation of the risk values was made. The parameters in the equation were given numerical values. Numerical values for each hazard were assigned using the descriptive category of high, medium and low. The vulnerability parameter was given numerical values from the socio-economic data according to the presence, or absence, of population and infrastructure/utility factors. Having numerical values assigned to them, the hazard and vulnerability factors could then be multiplied to obtain the risk values. The ranking of the areas according to the hazard and vulnerability parameters was used to map out the volcanic risks for Canlaon Volcano. A total of 12 risk maps were produced covering up to the municipal and city level of mapping: one map for each of the two factors (lives; infrastructure and/or utility) and a combination of the two with respect to 1) each one of the volcanic hazards considered; and 2) the combination of all the three hazards.