Cameroon Malaria Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dictionnaire Des Villages Du Département Bamoun 42 P

OFFICE DE LA RECHERCHE REfIlUBLIQUE FEDERALE SCIENTIFIQUE ET 'rECHNIQUE DU OUTRE-MER CAMEROUN CENTRE OR5TOM DE YAOUNDE 1 DICTIONNAIRE DES VILLAGES . DU DEPARTEMENT BAMOUN ~prèS la documentation réunie ~ ~ction de Géographiy de l'ORS~ REPERTOIRE GEOGRAPHIQUE DU CAMEROUN FASCICULE n° 16 SH. n° 44 YAOUNDE Janvier 1968 REPERTOIRE GEOGRAPHIQUE DU CAMEROUN Fesc. Tabl.eau de là population du Cameroun, 68 p. Fév. 1965 SH. N° 17 Fasc. 2 Dictionnaire des villages du Dia et Lobo, 89 p. Juin 1965 SH. N° 22 Fasc. 3 Dictionnaire des ~illages de la Haute-Sanaga, 53 p. Août 1965 SH. N° 23 Fasc. 4 Dictionnaire des villages du Nyong et Mfoumou, ~~ p. Octobre 1965 SH. N° ?4 Fasc. 5 Dictionnaire des villages du Nyong et Soo 45 p. Novembre 1965 SH. N° 25 Fasc. 6 Dictionnaire des villages du l'-Jtem 126 p. Décembre 1965 SH. N° 26 Fasc. 7 Dictionnaire des villages de la Mefou 108 p. Janvier 1966 SH. N" 27 Fasc. 8 Dictionnaire des villages du Nyong et Kellé 51 p. Février 1966 5H. N° 28 Fasc. 9 Dictionnaire des villages de la Lékié 71 p. Mars 1966 SH. N° 29 Fasc. 10 Dictionnaire des villages de Kribi P. Mars 1966 SH. N° 30 Fasc. 11 Dictionnaire des villages du Mbam 60 P. Mai 1966 SH. N° 31 Fasc. 12 Dictionnaire des villages de Boumba Ngoko 34 p. Juin 1966 SH 39 Fasc. 13 Dictionnaire des villages de Lom-et-Djérem 35 p. Juillet 1967 SH. 40 Fasc. 14 Dictionnaire des villages de la Kadei 52 p. Août 1967 SH. 41 Fasc. -

Cholera Outbreak

Emergency appeal final report Cameroon: Cholera outbreak Emergency appeal n° MDRCM011 GLIDE n° EP-2011-000034-CMR 31 October 2012 Period covered by this Final Report: 04 April 2011 to 30 June 2012 Appeal target (current): CHF 1,361,331. Appeal coverage: 21%; <click here to go directly to the final financial report, or here to view the contact details> Appeal history: This Emergency Appeal was initially launched on 04 April 2011 for CHF 1,249,847 for 12 months to assist 87,500 beneficiaries. CHF 150,000 was initially allocated from the Federation’s Disaster Relief Emergency Fund (DREF) to support the national society in responding by delivering assistance. Operations update No 1 was issued on 30 May 2011 to revise the objectives and budget of the operation. Operations update No 2 was issued on 31st May 2011 to provide financial statement against revised budget. Operations update No 3 was issued on 12 October 2011 to summarize the achievements 6 months into the operation. Operations update No 4 was issued on 29 February 2012 to extend the timeframe of the operation from 31st March to 30 June 2012 to cover the funding agreement with the American Embassy in Cameroon. PBR No M1111087 was submitted as final report of this operation to the American Embassy in Cameroon on 03 August 2012. Throughout the operation, Cameroon Red Cross volunteers sensitized the populations on PBR No M1111127 was submitted as final report of this how to avoid cholera. Photo/IFRC operation to the British Red Cross on 14 August 2012. Summary: A serious cholera epidemic affected Cameroon since 2010. -

NW SW Presence Map Complete Copy

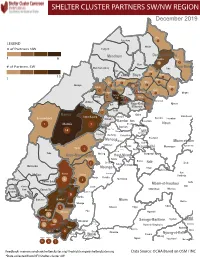

SHELTER CLUSTER PARTNERS SW/NWMap creation da tREGIONe: 06/12/2018 December 2019 Ako Furu-Awa 1 LEGEND Misaje # of Partners NW Fungom Menchum Donga-Mantung 1 6 Nkambe Nwa 3 1 Bum # of Partners SW Menchum-Valley Ndu Mayo-Banyo Wum Noni 1 Fundong Nkum 15 Boyo 1 1 Njinikom Kumbo Oku 1 Bafut 1 Belo Akwaya 1 3 1 Njikwa Bui Mbven 1 2 Mezam 2 Jakiri Mbengwi Babessi 1 Magba Bamenda Tubah 2 2 Bamenda Ndop Momo 6b 3 4 2 3 Bangourain Widikum Ngie Bamenda Bali 1 Ngo-Ketunjia Njimom Balikumbat Batibo Santa 2 Manyu Galim Upper Bayang Babadjou Malentouen Eyumodjock Wabane Koutaba Foumban Bambo7 tos Kouoptamo 1 Mamfe 7 Lebialem M ouda Noun Batcham Bafoussam Alou Fongo-Tongo 2e 14 Nkong-Ni BafouMssamif 1eir Fontem Dschang Penka-Michel Bamendjou Poumougne Foumbot MenouaFokoué Mbam-et-Kim Baham Djebem Santchou Bandja Batié Massangam Ngambé-Tikar Nguti Koung-Khi 1 Banka Bangou Kekem Toko Kupe-Manenguba Melong Haut-Nkam Bangangté Bafang Bana Bangem Banwa Bazou Baré-Bakem Ndé 1 Bakou Deuk Mundemba Nord-Makombé Moungo Tonga Makénéné Konye Nkongsamba 1er Kon Ndian Tombel Yambetta Manjo Nlonako Isangele 5 1 Nkondjock Dikome Balue Bafia Kumba Mbam-et-Inoubou Kombo Loum Kiiki Kombo Itindi Ekondo Titi Ndikiniméki Nitoukou Abedimo Meme Njombé-Penja 9 Mombo Idabato Bamusso Kumba 1 Nkam Bokito Kumba Mbanga 1 Yabassi Yingui Ndom Mbonge Muyuka Fiko Ngambé 6 Nyanon Lekié West-Coast Sanaga-Maritime Monatélé 5 Fako Dibombari Douala 55 Buea 5e Massock-Songloulou Evodoula Tiko Nguibassal Limbe1 Douala 4e Edéa 2e Okola Limbe 2 6 Douala Dibamba Limbe 3 Douala 6e Wou3rei Pouma Nyong-et-Kellé Douala 6e Dibang Limbe 1 Limbe 2 Limbe 3 Dizangué Ngwei Ngog-Mapubi Matomb Lobo 13 54 1 Feedback: [email protected]/ [email protected] Data Source: OCHA Based on OSM / INC *Data collected from NFI/Shelter cluster 4W. -

The Bamendjin Dam and Its Implications in the Upper Noun Valley, Northwest Cameroon

Journal of Sustainable Development; Vol. 7, No. 6; 2014 ISSN 1913-9063 E-ISSN 1913-9071 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education The Bamendjin Dam and Its Implications in the Upper Noun Valley, Northwest Cameroon Richard Achia Mbih1, Stephen Koghan Ndzeidze2, Steven L. Driever1 & Gilbert Fondze Bamboye3 1 Department of Geosciences, University of Missouri-Kansas City, Kansas City, USA 2 Department of Rangeland Ecology and Management, and Integrated Plant Protection Center, Oregon State University, Corvallis, USA 3 Department of Geography, University of Yaoundé I, Cameroon Correspondence: Richard Achia Mbih, Department of Geosciences, University of Missouri-Kansas City, 5100 Rockhill Road, Kansas City, MO 64110, USA. E-mail: [email protected] Received: October 8, 2014 Accepted: October 23, 2014 Online Published: November 23, 2014 doi:10.5539/jsd.v7n6p123 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/jsd.v7n6p123 Abstract Understanding the environmental consequences and socio-economic importance of dams is vital in assessing the effects of the Bamendjin dam in the development of agrarian communities in the Upper Noun Valley (UNV) in Northwest Cameroon. The Bamendjin dam drainage basin and its floodplain are endowed with abundant water resources and rich biodiversity, however, poverty is still a dominant factor that accounts for unsustainable management of natural resources by the majority of rural inhabitants in the area. The dam was created in 1975 and has since then exacerbated the environmental conditions and human problems of the region due to lack of flood control during rainy seasons, lost hope of improved navigation system, unclean drinking water sources, population growth, rising unemployment, deteriorating environmental health issues, resettlement problems and land use conflicts, especially farmer-herder conflicts. -

Commodification of Care and Its Effects on Maternal Health in the Noun Division (West Region – Cameroon) Ibrahim Bienvenu Mouliom Moungbakou

Moungbakou BMC Medical Ethics 2018, 19(Suppl 1):43 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12910-018-0286-1 RESEARCH Open Access Commodification of care and its effects on maternal health in the Noun division (West Region – Cameroon) Ibrahim Bienvenu Mouliom Moungbakou Abstract Background: Since the mid-1980s, there has been a gradual ethical drift in the provision of maternal care in African health facilities in general, and in Cameroon in particular, despite government efforts. In fact, in Cameroon, an increasing number of caregivers are reportedly not providing compassionate care in maternity services. Consequently, many women, particularly the financially vulnerable, experience numerous difficulties in accessing these health services. In this article, we highlight the unequal access to care in public maternity services in Cameroon in general and the Noun Division in particular. Methods: For this study, in addition to documentary review, two qualitative data collection techniques were used: direct observation and individual interviews. Following the field work, the observation data were categorized and analyzed to assess their relevance and significance in relation to the topics listed in the observation checklist. Interviews were recorded using a dictaphone; they were subsequently transcribed and the data categorized and coded. After this stage, an analysis grid was constructed for content analysis of the transcripts, to study the frequency of topics addressed during the interviews, as well as divergences and convergences among the respondents. Results: The results of this data analysis showed that money has become the driving force in service provision. As such, it is the patient’s economic capital that counts. Considered “clients”, pregnant women without sufficient financial resources wait long hours in corridors; some die in pain under the indifferent gaze of the professionals who are supposed to take care of them. -

Cameroon's Logging Industry: Structure, Economic Importance and Effects of Devaluation

OCCASIONAL PAPER NO. 14 ISSN 0854-9818 Aug. 1998 CameroonÕs Logging Industry: Structure, Economic Importance and Effects of Devaluation Richard EbaÕa Atyi, Tropenbos Cameroon Programme CIFOR in collaboration with the Tropenbos Foundation and The Tropenbos Cameroon Programme CIFOR CENTER FOR INTERNATIONAL FORESTRY RESEARCH CENTER FOR INTERNATIONAL FORESTRY RESEARCH office address: Jalan CIFOR, Situ Gede, Sindangbarang, Bogor 16680, Indonesia mailing address: P.O. Box 6596 JKPWB, Jakarta 10065, Indonesia tel.: +62 (251) 622622 fax: +62 (251) 622100 email: [email protected] WWW: http://www.cgiar.org/cifor The CGIAR System The Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR) is an informal association of 41 public and private sector donors that supports a network of sixteen interna- tional agricultural research institutes, CIFOR being the newest of these. The Group was established in 1971. The CGIAR Centers are part of a global agricultural research system which endeavour to apply international scientific capacity to solution of the problems of the worldÕs disadvantaged people. CIFOR CIFOR was established under the CGIAR system in response to global concerns about the social, environmental and economic consequences of loss and degradation of forests. It operates through a series of highly decentralised partnerships with key institutions and/or individuals throughout the developing and industrialised worlds. The nature and duration of these partnerships are determined by the specific research problems being addressed. This research -

Research Article Safety Measures and Health Issues Among Pesticide

International Journal of Medical Science and Clinical Invention 5(08): 4013-4019, 2018 DOI:10.18535/ijmsci/v5i8.08 ICV 2016: 77.2 e-ISSN:2348-991X, p-ISSN: 2454-9576 © 2018,IJMSCI Research Article Safety Measures and Health Issues among Pesticide Applicators in Foumbot Agricultural Area, West Region, Cameroon 1Sonchieu Jean*, 1Fotsing Stephano Franklin, 2Akono Edouard Nantia, 3Ngassoum Martin Benoit 1Department of Social Economy and Family Management, Higher Technical Teacher Training College, University of Bamenda, PO. Box 39 Bamenda, Cameroon 2Department of Biochemistry, Faculty of Science, University of Bamenda, Bambili, Cameroon 3Department of Applied Chemistry, ENSAI, University of Ngaoundere, PO Box: 455, Ngaoundéré, Cameroon Abstract: Several reports have raised the misuse of pesticides in the protection of crops in the Foumbot agricultural area. This study aims at evaluating the health status of pesticide operators in the said area. 127 farmers were interviewed out of which 30 were selected for medical check-up. A diagnostic was done on the liver status and a physical checkup on the eyes, the respiratory system and the skin of 30 selected pesticide applicators following the medical laboratory routine examination. The skin of users was diagnosed for itching, prickling, irritation and burns; the eyes for sight troubles, stinging, wateriness; the respiratory system for catarrh, cough , difficulties in breathing and chest constriction; the liver status was estimated using two enzymes: Aspartate Amino-Transferase (ASAT) and Alanine Amino-Transferase (ALT). As results: pesticides used are from three main classes and belong to classes II and III toxicity: insecticides (cypermethrin, most used), fungicides (ethylenebisdithiocarbamates) and herbicides (paraquat and glyphosate). -

Journal of Agricultural, Life and Environmental Sciences

Vol.32, Special Issue, pp.205-215, 2020 Journal of Agricultural, Life and Environmental Sciences pISSN 2233-8322, eISSN 2508-870X RESEARCH ARTICLE https://doi.org/10.22698/jales.20200018 Factors Influencing the Technical Efficiency of Small-scale Maize Farmers in the Foumbot and Foumban Subdivisions in Cameroon Achu, E.1* and D. S. Lee2* 1Former Master’s Student and Agricultural Economist, Obang Valley Cooperative Society, Cameroon 2Associate Professor, Department of International Development Cooperation, Kangwon National University, Chuncheon 24341, Korea *Corresponding author: Emmanuel, A. (E-mail: [email protected]), Lee, D. S. (E-mail: [email protected]) A B S T R A C T Received: 28 September 2020 This study determined the technical efficiency of the maize production by small-scale farmers in Revised: 14 October 2020 the Foumbot and Foumban subdivisions in Cameroon. Multistage sampling technique was used to Accepted: 20 October 2020 sample a total of 148 maize-farming households, i.e., 77 in Foumbot and 71 in Foumban. A semi-structured questionnaire was administered to collect data on farm inputs and outputs and on farm and farmer characteristics. Data envelopment analysis was conducted to estimate efficiency scores, while a Tobit regression analysis model was used to determine the influence of farm and farmer characteristics on technical efficiency. The results indicated that the average technical efficiency was of 35%. This implies that the technical efficiency of the maize production in the Foumbot and Foumban subdivisions is low and could be enhanced by 65% through the improved use of available resources, given the prevailing state of technology. -

Pdf | 300.72 Kb

Report Multi-Sector Rapid Assessment in the West and Littoral Regions Format Cameroon, 25-29 September 2018 1. GENERAL OVERVIEW a) Background What? The humanitarian crisis affecting the North-West and the South-West Regions has a growing impact in the bordering regions of West and Littoral. Since April 2018, there has been a proliferation of non-state armed groups (NSAG) and intensification of confrontations between NSAG and the state armed forces. As of 1st October, an estimated 350,000 people are displaced 246,000 in the South-West and 104,000 in the North-West; with a potential increment due to escalation in hostilities. Why? An increasing number of families are leaving these regions to take refuge in Littoral and the West Regions following disruption of livelihoods and agricultural activities. Children are particularly affected due to destruction or closure of schools and the “No School” policy ordered by NSAG since 2016. The situation has considerably evolved in the past three months because of: i) the anticipated security flashpoints (the start of the school year, the “October 1st anniversary” and the elections); ii) the increasing restriction of movement (curfew extended in the North-West, “No Movement Policy” issued by non-state actors; and iii) increase in both official and informal checkpoints. Consequently, there has been a major increase in the number of people leaving the two regions to seek safety and/or to access economic and educational opportunities. Preliminary findings indicate that IDPs are facing similar difficulties and humanitarian needs than the one reported in the North-West and the South-West regions following the multisectoral needs assessment done in March 2018. -

CAMEROON, FIRST QUARTER 2020: Update on Incidents According to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) Compiled by ACCORD, 23 June 2020

CAMEROON, FIRST QUARTER 2020: Update on incidents according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) compiled by ACCORD, 23 June 2020 Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality Number of reported fatalities National borders: GADM, November 2015b; administrative divisions: GADM, November 2015a; in- cident data: ACLED, 20 June 2020; coastlines and inland waters: Smith and Wessel, 1 May 2015 CAMEROON, FIRST QUARTER 2020: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 23 JUNE 2020 Contents Conflict incidents by category Number of Number of reported fatalities 1 Number of Number of Category incidents with at incidents fatalities Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality 1 least one fatality Violence against civilians 162 92 263 Conflict incidents by category 2 Battles 111 50 316 Development of conflict incidents from March 2018 to March 2020 2 Strategic developments 39 0 0 Protests 23 1 1 Methodology 3 Riots 14 4 5 Conflict incidents per province 4 Explosions / Remote 10 7 22 violence Localization of conflict incidents 4 Total 359 154 607 Disclaimer 5 This table is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 20 June 2020). Development of conflict incidents from March 2018 to March 2020 This graph is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 20 June 2020). 2 CAMEROON, FIRST QUARTER 2020: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 23 JUNE 2020 Methodology on what level of detail is reported. Thus, towns may represent the wider region in which an incident occured, or the provincial capital may be used if only the province The data used in this report was collected by the Armed Conflict Location & Event is known. -

Anschaire Aveved Doctoral Dissertation

Uncanny Autochthons: The Bamileke Facing Ethnic Territorialization in Cameroon Anschaire Aveved Submitted in partial fulfillment of the Requirement for the degree Of Doctor of Philosophy In the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2015 © 2015 Anschaire Aveved All rights reserved ABSTRACT Uncanny Autochthons: The Bamileke Facing Ethnic Territorialization in Cameroon Anschaire Aveved The Bamileke in contemporary Cameroon are known by the services of the General Delegation for National Security as one of the approximately 200 ethnic groups that have been assigned a registration number, and they must like all citizens formally identify their ethnic group at the time of national identification. Unlike most Cameroonians who identify with a primary language, the Bamileke usually identify with a chieftaincy or a village of origin, which may not always correspond with a distinctive language. This situation has led the police to hold a map of chieftaincies during registration in order to assist the self-identification of those whose declared place of origin is located in the former Bamileke Region. While this operation reveals the extent to which the Bamileke ethnonym corresponds to a linguistic umbrella term and sets apart the Bamileke as an ethnic group in state records, it also highlights the general assumption that one can match every registered ethnic group with a discrete region of the country’s territory. The structure that grounds this assumption is referred to as ethnic territorialization in this dissertation and is critically examined from the vantage point of ethnographic exhibition, identification with homelands, political competition, and colonial history. The legibility and traceability of both ethnic identity and putative home villages that come with national identification in Cameroon contrast distinctly with the generally repressed character of ethnicity in national politics and state institutions that have the representation of the nation as one of their main objectives. -

1. General Overview

Report Multi-Sector Rapid Assessment in the West and Littoral Regions Format Cameroon, 25-29 September 2018 1. GENERAL OVERVIEW a) Background What? The humanitarian crisis affecting the North-West and the South-West Regions has a growing impact in the bordering regions of West and Littoral. Since April 2018, there has been a proliferation of non-state armed groups (NSAG) and intensification of confrontations between NSAG and the state armed forces. As of 1st October, an estimated 350,000 people are displaced 246,000 in the South-West and 104,000 in the North-West; with a potential increment due to escalation in hostilities. Why? An increasing number of families are leaving these regions to take refuge in Littoral and the West Regions following disruption of livelihoods and agricultural activities. Children are particularly affected due to destruction or closure of schools and the “No School” policy ordered by NSAG since 2016. The situation has considerably evolved in the past three months because of: i) the anticipated security flashpoints (the start of the school year, the “October 1st anniversary” and the elections); ii) the increasing restriction of movement (curfew extended in the North-West, “No Movement Policy” issued by non-state actors; and iii) increase in both official and informal checkpoints. Consequently, there has been a major increase in the number of people leaving the two regions to seek safety and/or to access economic and educational opportunities. Preliminary findings indicate that IDPs are facing similar difficulties and humanitarian needs than the one reported in the North-West and the South-West regions following the multisectoral needs assessment done in March 2018.