Climate Change, Migration, and Conflict in Northwest Africa Rising Dangers and Policy Options Across the Arc of Tension

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

War and Insurgency in the Western Sahara

Visit our website for other free publication downloads http://www.StrategicStudiesInstitute.army.mil/ To rate this publication click here. STRATEGIC STUDIES INSTITUTE The Strategic Studies Institute (SSI) is part of the U.S. Army War College and is the strategic-level study agent for issues relat- ed to national security and military strategy with emphasis on geostrategic analysis. The mission of SSI is to use independent analysis to conduct strategic studies that develop policy recommendations on: • Strategy, planning, and policy for joint and combined employment of military forces; • Regional strategic appraisals; • The nature of land warfare; • Matters affecting the Army’s future; • The concepts, philosophy, and theory of strategy; and, • Other issues of importance to the leadership of the Army. Studies produced by civilian and military analysts concern topics having strategic implications for the Army, the Department of Defense, and the larger national security community. In addition to its studies, SSI publishes special reports on topics of special or immediate interest. These include edited proceedings of conferences and topically-oriented roundtables, expanded trip reports, and quick-reaction responses to senior Army leaders. The Institute provides a valuable analytical capability within the Army to address strategic and other issues in support of Army participation in national security policy formulation. Strategic Studies Institute and U.S. Army War College Press WAR AND INSURGENCY IN THE WESTERN SAHARA Geoffrey Jensen May 2013 The views expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Army, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. -

Does Cyclical Explanation Provide Insight to Protracted Conflicts in Africa?

Arabian Journal of Business and Management Review (Nigerian Chapter) Vol. 3, No. 11, 2015 DOES CYCLICAL EXPLANATION PROVIDE INSIGHT TO PROTRACTED CONFLICTS IN AFRICA? David Oladimeji Alao, Ph.D Department of Political Science and Public Administration Veronica Adeleke School of Social Sciences, Babcock University, Ilishan-Remo, Ogun State +2348035572279. [email protected] Ngozi Nwogwugwu, PhD Department of Political Science and Public Administration Veronica Adeleke School of Social Sciences, Babcock University, Ilishan-Remo, Ogun State. [email protected] ABSTRACT Africa accounted for greater percentage of violent conflict globally since the end of the cold war. There had been resurgence of violent conflict in many nations after what had been presumed to be peaceful resolution of such conflicts. Among the countries that have had recurring violent conflicts are Mali, Central African Republic, Egypt among others. This had resulted in formulation of many theories, largely revolving around causative and redemptive measures. The resurgence of deep rooted and protracted conflicts informed the paper which examined the cyclical model of conflicts in Africa. The cyclical model points government and practitioners to the defects of the haphazard conflict resolution measures which show lack of political will to combine causative and redemptive measures in ensuring peaceful resolution of conflicts. INTRODUCTION The joy and expectations of nations in Africa becoming independent was short-lived as conflicts and crises of multidimensional nature dotted the whole map turning citizens to refugees within and outside their nations. According to DFID (2001) report, 10 of the twenty four nations of the World engulfed in direct violence or outright war between 1980 and 1994 were located in Africa. -

Arrêt N° 009/2016/CC/ME Du 07 Mars 2016

REPUBLIQUE DU NIGER FRATERNITE-TRAVAIL-PROGRES COUR CONSTITUTIONNELLE Arrêt n° 009/CC/ME du 07 mars 2016 La Cour constitutionnelle statuant en matière électorale, en son audience publique du sept mars deux mil seize tenue au palais de ladite Cour, a rendu l’arrêt dont la teneur suit : LA COUR Vu la Constitution ; Vu la loi organique n° 2012-35 du 19 juin 2012 déterminant l’organisation, le fonctionnement de la Cour constitutionnelle et la procédure suivie devant elle ; Vu la loi n° 2014-01 du 28 mars 2014 portant régime général des élections présidentielles, locales et référendaires ; Vu le décret n° 2015-639/PRN/MISPD/ACR du 15 décembre 2015 portant convocation du corps électoral pour les élections présidentielles ; Vu l’arrêt n° 001/CC/ME du 9 janvier 2016 portant validation des candidatures aux élections présidentielles de 2016 ; Vu la lettre n° 250/P/CENI du 27 février 2016 du président de la Commission électorale nationale indépendante (CENI) transmettant les résultats globaux provisoires du scrutin présidentiel 1er tour, aux fins de validation et proclamation des résultats définitifs ; Vu l’ordonnance n° 013/PCC du 27 février 2016 de Madame le Président portant désignation d’un Conseiller-rapporteur ; Vu les pièces du dossier ; Après audition du Conseiller-rapporteur et en avoir délibéré conformément à la loi ; EN LA FORME 1 Considérant que par lettre n° 250 /P/CENI en date du 27 février 2016, enregistrée au greffe de la Cour le même jour sous le n° 18 bis/greffe/ordre, le président de la Commission électorale nationale indépendante (CENI) a saisi la Cour aux fins de valider et proclamer les résultats définitifs du scrutin présidentiel 1er tour du 21 février 2016 ; Considérant qu’aux termes de l’article 120 alinéa 1 de la Constitution, «La Cour constitutionnelle est la juridiction compétente en matière constitutionnelle et électorale.» ; Que l’article 127 dispose que «La Cour constitutionnelle contrôle la régularité des élections présidentielles et législatives. -

Sitwa Report on Infrastructure Development

SITWA PROJECT: STRENGTHENING THE INSTITUTIONS FOR TRANSBOUNDARY WATER MANAGEMENT IN AFRICA CONSULTANCY SERVICES TO ASSESS THE NEEDS AND PREPARE AN ACTION PLAN FOR SITWA/ANBO SUPPORT SERVICES IN INFRASTRUCTURE DEVELOPMENT IN THE AFRICAN RIVER BASIN ORGANIZATIONS SITWA REPORT ON INFRASTRUCTURE DEVELOPMENT This document has been produced with the financial assistance of the European Union. The views expressed herein can in no way be taken to reflect the official opinion of the European Union RAPPORT SITWA SUR LE DÉVELOPPEMENT DES INFRASTRUCTURES DANS LES OBF AFRICAINS 3 Table des matiÈRES Table des matières ...................................................................................... 3 AbrEviations ............................................................................................... 5 Acknowledgements .................................................................................... 7 Executive summary .................................................................................... 8 List of tables .............................................................................................. 9 List of figures ............................................................................................ 9 1. Background and objectives of the consultancy ........................................ 10 1.1 ANBO’s historical background and objectives ............................................................................. 10 1.2 Background and objectives of SITWA ......................................................................................... -

Hot Age Or Ice Age TABLE of CONTENTS

Imprint: Publisher: TerraFuture AG (i.Gr.) Hauptstr. 193 50169 Kerpen Germany Author: Wolf-Walter Stinnes (M.Sc.Phys.) Internet: www.TerraFuture.ag E-Mail: [email protected] Copyright ©2019 TerraFuture AG (i.Gr.) All rights reserved, in particular the right of duplication, distribution and/or translation. No part of the work may be reproduced in any form (including photocopying, microfilm or any other process) or stored, processed, duplicated or distributed using electronic or mechanical methods without the written consent of TerraFuture AG (i.Gr.). 2 Hot Age or Ice Age TABLE OF CONTENTS A. Author �������������������������������������������������������������������������������5 B. What are the Real Problems of Mankind ������������������������6 C. Why and how does the Earth´s Atmosphere warm up? ���������������������������������������������������������������������������8 1. Visible Solar Radiation �������������������������������������������������9 2. Invisible Solar or Space Radiation, infrared (IR) or ultraviolet (UV) ��������������������������������������������������������10 3. Heat Conduction from the inner Earth to its Surface: . 11 4. Heat Transfer from the Earth´s hot surface into the atmosphere by heat conduction ��������������������������� 11 5. Heat transfer into the atmosphere by convection ������� 11 D. The Role of Greenhouse Gases ....................................12 1. The Greenhouse Gas CO2: ����������������������������������������12 2. CO2 versus Water Vapor: �������������������������������������������12 3. The pretension -

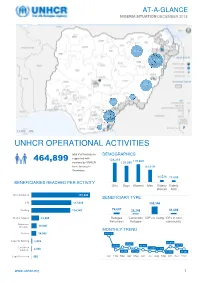

Unhcr Operational Activities 464,899

AT-A-GLANCE NIGERIA SITUATION DECEMBER 2018 28,280 388,208 20,163 1,770 4,985 18.212 177 Bénéficiaires Reached UNHCR OPERATIONAL ACTIVITIES total # of individuals DEMOGRAPHICS supported with 464,899 128,318 119,669 services by UNHCR 109,080 from January to 81,619 December; 34,825 of them from Mar-Apr 14,526 11,688 2018 BENEFICIARIES REACHED PER ACTIVITY Girls Boys Women Men Elderly Elderly Women Men Documentation 172,800 BENEFICIARY TYPE CRI 117,838 308,346 Profiling 114,747 76,607 28,248 51,698 Shelter Support 22,905 Refugee Cameroon IDPs in Camp IDPs in host Returnees Refugee community Awareness Raising 16,000 MONTHLY TREND Referral 14,956 140,116 Capacity Building 2,939 49,819 39,694 24,760 25,441 34,711 Livelihood 11,490 11,158 Support 2,048 46,139 37,118 13,770 30,683 Legal Protection 666 Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec www.unhcr.org 1 NIGERIA SITUATION AT-A-GLANCE / DEC 2018 CORE UNHCR INTERVENTIONS IN NIGERIA UNHCR Nigeria strategy is based on the premise that the government of Nigeria assumes the primary responsibility to provide protection and assistance to persons of concern. By building and reinforcing self-protection mechanisms, UNHCR empowers persons of concern to claim their rights and to participate in decision-making, including with national and local authorities, and with humanitarian actors. The overall aim of UNHCR Nigeria interventions is to prioritize and address the most serious human rights violations, including the right to life and security of persons. -

'Parti Nigérien Pour La Démocratie Et Le Socialisme' (PNDS)

Niger Klaas van Walraven President Mahamadou Issoufou and his ruling ‘Parti Nigérien pour la Démocratie et le Socialisme’ (PNDS) consolidated their grip on power, though not without push- ing to absurd levels the unorthodox measures by which they hoped to strengthen their position. Opposition leader Hama Amadou of the ‘Mouvement Démocratique Nigérien’ (Moden-Lumana), who had been arrested in 2015 for alleged involvement in a baby-trafficking scandal, remained in detention. He was allowed to contest the 2016 presidential elections from his cell. Issoufou emerged victorious, though not without an unexpected run-off. The parliamentary polls allowed the PNDS to boost its position in the National Assembly. Although the elections took place in an atmosphere of calm, they were marred by authoritarian interventions, including the arrest of several members of the opposition. The ‘Mouvement National pour la Société de Développement’ (MNSD) of Seini Oumarou had to cede its leader- ship of the opposition to Amadou’s Moden, which ended ahead of the MNSD in the Assembly. In August, the MNSD joined the presidential majority, which did not bode well for the possibility of political alternation in the future. National security was tested by frequent attacks by Boko Haram fighters in the south-east and raids by insurgents based in Mali. While the humanitarian situation in the south-east © koninklijke brill nv, leiden, 2�17 | doi 1�.1163/9789004355910_016 Niger 129 worsened, the army managed to strike back and engage in counter-insurgency oper- ations together with forces from Chad, Nigeria and Cameroon. Overall, the country held its own, despite being sandwiched between security challenges that caused some serious losses. -

Region: West Africa (14 Countries) (Benin, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Chad, Côte D’Ivoire, Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea Bissau, Mali, Niger, Senegal, Togo)

Region: West Africa (14 Countries) (Benin, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Chad, Côte d’Ivoire, Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea Bissau, Mali, Niger, Senegal, Togo) Project title: Emergency assistance for early detection and prevention of avian influenza in Western Africa Project number: TCP/RAF/3016 (E) Starting date: November 2005 Completion date: April 2007 Government counterpart Ministries of Agriculture responsible for project execution: FAO contribution: US$ 400 000 Signed: ..................................... Signed: ........................................ (on behalf of Government) Jacques Diouf Director-General (on behalf of FAO) Date of signature: ..................... Date of signature: ........................ I. BACKGROUND AND JUSTIFICATION In line with the FAO/World Organization for Animal Health (OIE) Global Strategy for the Progressive Control of Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza (HPAI), this project has been developed to provide support to the regional grouping of West African countries to strengthen emergency preparedness against the eventuality of HPAI being introduced into this currently free area. There is growing evidence that the avian influenza, which has been responsible for serious disease outbreaks in poultry and humans in several Asian countries since 2003, is spread through a number of sources, including poor biosecurity at poultry farms, movement of poultry and poultry products and live market trade, illegal and legal trade in wild birds. Although unproven, it is also suspected that the virus could possibly be carried over long distances along the migratory bird flyways to regions previously unaffected (Table 1) is a cause of serious concern for the region. Avian influenza subtype H5N1 could be transported along these routes to densely populated areas in the South Asian Subcontinent and to the Middle East, Africa and Europe. -

Mapping of Climate Change Threats and Human Development Impacts in the Arab Region

Arab Human Development Report Research Paper Series Mapping of Climate Change Threats and Human Development Impacts in the Arab Region Balgis Osman Elasha United Nations Development Programme Regional Bureau for Arab States United Nations Development Programme Regional Bureau for Arab States Arab Human Development Report Research Paper Series 2010 Mapping of Climate Change Threats and Human Development Impacts in the Arab Region Balgis Osman Elasha The Arab Human Development Report Research Paper Series is a medium for sharing recent research commissioned to inform the Arab Human Development Report, and fur- ther research in the field of human development. The AHDR Research Paper Series is a quick-disseminating, informal publication whose titles could subsequently be revised for publication as articles in professional journals or chapters in books. The authors include leading academics and practitioners from the Arab countries and around the world. The findings, interpretations and conclusions are strictly those of the authors and do not neces- sarily represent the views of UNDP or United Nations Member States. The present paper was authored by Balgis Osman Elasha. * * * Balgis Osman-Elasha is a Climate Change Adaptation Expert at the African Development Bank. She holds a Bachelor’s Degree (with Honours) and a Doctorate in Forestry Science, and a Master’s Degree in Environmental Science. She has extensive experience in climate change research, with a focus on the human dimensions of global environmental change (GEC) and sustainable development. She is a winner of the UNEP Champions of the Earth award, 2008, and a member of the IPCC Lead Authors Nobel Peace Prize winners in 2007. -

List of Previous Grant Projects

Toyota Environmental Activities Grant Program 2019 Recipients Grant Catego Theme Project Description Organization Country ry "Kaeng Krachan Forest Complex: Future Conference of Earth Creation Project Through Local Knowledge Environment from Thailand and Traditional Knowledge" for Sustainable Akita Environmental Innovation Japan International Orangutan Conservation Activity in Forestry Promotion Collaboration with the Government and Indonesia and Cooperation Residents in East Kalimantan, Indonesia Center Environmental Conservation Activity Through the Production Support of Organic Fertilizers from Palm Oil Waste and the Agricultural Kopernik Japan Indonesia Education for Farmers to Receive the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO) Certification in Indonesia Biodiversi Nippon Practical Environmental Education Project in ty International Collaboration with Children, Women, and the Cooperation for India Government in a Rural Village in Bodh Gaya, Community India Development Star Anise Peace Project Project -Widespread Adoption of Agroforestry with a Barefoot Doctors Myanmar Overse Focus on Star Anise in the Ethnic Minority Group as Regions in Myanmar- Sustainable Management of the Mangrove Forest in Uto Village, Myanmar, as well as Ramsar Center Share Their Experiences to Nearby Villages Myanmar Japan and Conduct Environmental Awareness Activities for Young Generations Patagonian Programme: Restoring Habitats Aves Argentinas Argentina for Endemic Wildlife Conservation Beautiful Forest Creation Activity at the Preah Pride of Asia: Preah -

Large Hydro-Electricity and Hydro-Agricultural Schemes in Africa

FAO AQUASTAT Dams Africa – 070524 DAMS AND AGRICULTURE IN AFRICA Prepared by the AQUASTAT Programme May 2007 Water Development and Management Unit (NRLW) Land and Water Division (NRL) Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) Dams According to ICOLD (International Commission on Large Dams), a large dam is a dam with the height of 15 m or more from the foundation. If dams are 5-15 metres high and have a reservoir volume of more than three million m3, they are also classified as large dams. Using this definition, there are more than 45 000 large dams around the world, almost half of them in China. Most of them were built in the 20th century to meet the constantly growing demand for water and electricity. Hydropower supplies 2.2% of the world’s energy and 19% of the world’s electricity needs and in 24 countries, including Brazil, Zambia and Norway, hydropower covers more than 90% of national electricity supply. Half of the world’s large dams were built exclusively or primarily for irrigation, and an estimated 30-40% of the 277 million hectares of irrigated lands worldwide rely on dams. As such, dams are estimated to contribute to 12-16% of world food production. Regional inventories include almost 1 300 large and medium-size dams in Africa, 40% of which are located in South Africa (517) (Figure 1). Most of these were constructed during the past 30 years, coinciding with rising demands for water from growing populations. Information on dam height is only available for about 600 dams and of these 550 dams have a height of more than 15 m. -

Elections in Niger: Casting Ballots Or Casting Doubts?

Elections in Niger: casting ballots or casting doubts? Given its centrality to the Sahel region, the international community needs Niger to remain a bulwark of stability. While recent data collected throughout the country shows an increase in motivation to participate in this month's election, doubts about the electoral process and concerns for longstanding development issues mar the enthusiasm. Birnin Gaouré, Dosso, December 2020 By Johannes Claes and Rida Lyammouri with Navanti staff Published in collaboration with Niger could see its first democratic transition since independence as the country heads to the polls for the presidential election on 27 December.1 Current President Mahamadou Issoufou has indicated he will respect his constitutionally mandated two-term limit of 10 years, passing the flag to his protégé, Mohamed Bazoum. Political instability looms, however, as Issoufou and Bazoum’s Nigerien Party for Democracy and Socialism (PNDS) and a coalition of opposition parties fail to agree on the rules of the game. Political inclusion and enhanced trust in the institutions governing Niger’s electoral process are key if the risk of political crisis is to be avoided. Niger’s central role in Western policymakers’ security and political agendas in the Sahel — coupled with its history of four successful coups in 1976, 1994, 1999, and 2010 — serve to caution Western governments that preserving stability through political inclusion should take top priority over clinging to a political candidate that best represents foreign interests.2 During a turbulent electoral year in the region, Western governments must focus on the long-term goals of stabilizing and legitimizing Niger’s political system as a means of ensuring an ally in security and migration matters — not the other way around.