Master Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tony Barry) Goes Undercover Into a Retirement Village in a Last-Ditch Effort to Catch the One That Got Away, the Old Crook Frank (John

REST FOR THE WICKED ONE- SENTENCE SUMMARY: Old cop Murray (Tony Barry) goes undercover into a retirement village in a last-ditch effort to catch the one that got away, the old crook Frank (John Bach). SHORT SYNOPSIS Murray (Tony Barry) is a retired cop with a new undercover mission. He‟s going into a retirement village to catch Frank (John Bach), the old crook he has never been able to pin a crime on. Murray is convinced Frank murdered fellow crim, Jimmy Booth, years ago but was never able to make the evidence stick. This time, he‟s going to make sure he gets his man. So, when people in the retirement village start dying, Murray is on the case. But as events go increasingly haywire, it becomes apparent that all is not as it seems with Frank. Or Murray. 1 LONG SYNOPSIS Murray (Tony Barry), an old cop in reflective mood, cuts a story from the newspaper about an explosion at a P-house. Another old man on a mobility scooter, Frank (John Bach) arrives at a run-down house, takes the drug dealers inside by surprise, guns them all down and watches gleefully as the house blows up. Murray packs his bag, gets ready to leave, his daughter Susan (Sara Wiseman) fussing over him, helping him with his tie. Susan notices Murray has left the iron turn on. Murray tells his grandson Max (George Beca) he‟s off on a top-secret mission. Max seems worried. Murray describes himself as “an old dog off to dig up some old bones.” At Knightsbridge Gardens Retirement Village, Murray and Susan are greeted by the manager, Miss Pomeroy (Elisabeth Easther). -

Peter Britos

PETER BRITOS A Conversation with Merata Mita This conversation took place on January 15th 2003 at about 8pm in Honolulu. We met at Merata’s home offi ce near the campus where her youngest son Hepi is fi nishing up his high school studies. Hepi met me downstairs and escorted me to his mother’s study, where Merata was working on a book about her life experiences. PB: My mother once told me that the cool thing about talking is that sometimes you don’t know a thing existed until you say it. The mere physicality of the act brings you to a place that you couldn’t have gotten to any other way. MM: I’ve known things. And until I’ve articulated them, they’ve never been con- scious. I like the experience of new places and new things and working out how to survive in different environments that are totally dif- ferent ones than I’m used to. But until you articulate that survival, it’s just living. Geoff [Murphy—her producer/director husband] never sees those challenges as being pleas- ant. But I thrive on that sort of thing. In the end I had to agree with him that we should move from Los Angeles. But I didn’t know where, and didn’t really care. And he always had in his mind that the ideal halfway point between Los Angeles and New Zealand would be Hawai`i. So I said aah Polynesians, hmmm. Okay. So we ended up here and he could make whatever film he was making. -

This Action Thriller Futuristic Historic Romantic Black Comedy Will Redefine Cinema As We Know It

..... this action thriller futuristic historic romantic black comedy will redefine cinema as we know it ..... XX 200-6 KODAK X GOLD 200-6 OO 200-6 KODAK O 1 2 GOLD 200-6 science-fiction (The Quiet Earth) while because he's produced some of the Meet the Feebles, while Philip Ivey composer for both action (Pitch Black, but the leading lady for this film, to Temuera Morrison, Robbie Magasiva, graduated from standing-in for Xena beaches or Wellywood's close DIRECTOR also spending time working on sequels best films to come out of this country, COSTUME (Out of the Blue, No. 2) is just Daredevil) and drama (The Basketball give it a certain edginess, has to be Alan Dale, and Rena Owen, with Lucy to stunt-doubling for Kill Bill's The proximity to green and blue screens, Twenty years ago, this would have (Fortress 2, Under Siege 2) in but because he's so damn brilliant. Trelise Cooper, Karen Walker and beginning to carve out a career as a Diaries, Strange Days). His almost 90 Kerry Fox, who starred in Shallow Grave Lawless, the late great Kevin Smith Bride, even scoring a speaking role in but there really is no doubt that the been an extremely short list. This Hollywood. But his CV pales in The Lovely Bones? Once PJ's finished Denise L'Estrange-Corbet might production designer after working as credits, dating back to 1989 chiller with Ewan McGregor and will next be and Nathaniel Lees as playing- Quentin Tarantino's Death Proof. South Island's mix of mountains, vast comes down to what kind of film you comparison to Donaldson who has with them, they'll be bloody gorgeous! dominate the catwalks, but with an art director on The Lord of the Dead Calm, make him the go-to guy seen in New Zealand thriller The against-type baddies. -

DA Alin Weismann 03:09

Die Darstellung von Māori im Spielfilm. Die Bildung einer indigenen Identität anhand eines Massenmediums. DIPLOMARBEIT zur Erlangung des Magistergrades der Philosophie an der Fakultät für Human- und Sozialwissenschaften der Universität Wien eingereicht von Alin Weismann Wien, März 2009 1 Inhaltsverzeichnis 1. Vorwort............................................................................................................................................7 2. Einleitung........................................................................................................................................9 3. Einführung in die Geschichte Neuseelands................................................................................12 3.1 Neuseeland vor der Kolonisierung.............................................................................12 3.2 Die Entdeckung Neuseelands.....................................................................................13 3.2.1 Die erste europäische Besiedlung...............................................................................14 3.2.2 Treaty of Waitangi.......................................................................................................15 3.3.3 Auswirkungen der europäischen Besiedlung auf die gesellschaftliche Situation.......16 3.4 Wirtschaft und Regierungsform von damals bis heute...............................................17 3.5 Die Modernisierung Neuseelands...............................................................................19 3.6 Neuseelands Population -

New Zealand Movies 2016

New zealand movies 2016 Continue In the early 1990s, the British Film Institute launched the Century of Cinema Series in an attempt to explore various examples of national cinemas around the world. The film, written and directed by Kiwi actor Sam Neill, has been a contributor to the project. Although his attitude to this topic has gradually changed, Sam Neill concluded in his documentary that the New zealand films are predominantly dark and brooding. This particular era of filmmaking began in the mid-1970s with the rise of the New Wave in cinema. Here, the themes that defined the way the New ealand public viewed themselves on screen put enormous creative pressure on local filmmakers. Since then, the national cinema of New york has experienced a number of unstable stages. Over the years, one of the greatest obstacles that the filmmakers of New York have had to overcome has been the high poppy syndrome of Kiwi culture. Local audiences have been impressed by the talents and creativity of their country's artists, so very few Kiwis will sit and watch New york made productions. National pride for the country's film industry has blossomed recently. Below is a list of the top ten examples of national cinema in New York. It is important to note that despite a key role in the creation of the influential film industry in New York, peter Jackson's Lord of the Rings and The Hobbit series were not included in this book. Instead, the films selected for the list are those that demonstrate the key characteristics of the country's culture. -

A Critical Examination of Film Archiving and Curatorial Practices in Aotearoa New Zealand Through the Life and Work of Jonathan Dennis

Emma Jean Kelly A critical examination of film archiving and curatorial practices in Aotearoa New Zealand through the life and work of Jonathan Dennis 2014 Communications School, Faculty of Design and Creative Technology Supervisors: Dr Lorna Piatti‐Farnell (AUT), Dr Sue Abel (University of Auckland) A thesis submitted to Auckland University of Technology in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy November 2014 1 Table of Contents Abstract ......................................................................................................................................................... 5 Acknowledgements:...................................................................................................................................... 6 Glossary of terms: ......................................................................................................................................... 8 Archival sources and key: ............................................................................................................................ 10 Interviews: .............................................................................................................................................. 10 1 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................. 11 2. Literature Review ................................................................................................................................... -

B1011 WDC WMFF Programme Final V3.Indd

WAIROA MAORI FILM FESTIVAL 2006 PRESENTED BY FESTIVAL PARTNERS Te Roopu Whakaata TAKITIMUMARAE Maori i te Wairoa Do you want to share your films with your mokopuna? Since its establishment 25 years ago, tens of thousands of items have been entrusted to the Archive by film makers and members of the public. Whether your work is professional or amateur, 35mm, Super 8 or VHS the Film Archive will preserve it in secure, climate controlled vaults and make it accessible for future generations. All material remains the property of the depositor and all rights remain unchanged. Talk to us now. See www.filmarchive.org.nz under Services: Acquisition and Deposit PATU! 1983 • R EWI’S LAST STAND, 1980 • SQUEEZE, 1980 • MUTTNIK, 2005 • STILL S COLLECTION, NEW ZEA LAND FILM ARCHIVE The Film Archive Te Anakura Whitia¯hua 84 Taranaki Street Wellington Tel: +64 4 384 7647 Fax: +64 4 382 9595 Email: [email protected] BROKEN BARRIER, 1952, STILL S COLLECTION, NZFA TE TAURIMA WHAKAATA MAORI I TE WAIROA Wairoa Maori Film Festival 2006 Koanga ~ Labour Weekend ~ October 20th to 23rd 2006 Gaiety Cinema & Theatre & Takitimu Marae, Wairoa CONTENTS WELCOME TO WAIROA 2 Message From The Chairperson 5 Message From the Festival Director 7 Festival Powhiri 9 Festival Awards Night & Musical Showcase 9 FESTIVAL AT A GLANCE 10 TE AO MAI NGA WHATU MAORI: THE WORLD THROUGH A MAORI LENS 12 SPECIAL SCREENINGS Opening Night Gala: Ngati 14 In Conversation with Barry Barclay 15 Mana Wairoa: From The Archives 16 Festival Centrepiece: Trail of Te Kooti 17 Closing Night: Mark II 18 NGA TERENGA MAHARA: STREAMS OF CONSCIOUSNESS 20 DRAMATIC FEATURES & SHORT FILM SELECTION Feathers of Peace 22 The Flight of the Albatross 27 Indigenous Short Film Showcase 28 Maori Merchant of Venice 29 No. -

Who We Are and What We Do And, Goodbye Andy Reid

SUMMER 2018 | ISSUE 79 The Screen Industry Guild Aotearoa New Zealand quarterly Farewell Geoff Murphy We review John Reid’s history of John O’Shea and Pacific Films Film Otago, Southland: Who we are and what we do And, goodbye Andy Reid www.screenguild.co.nz Cover your cast & crew Looking at a location that requires on site marquees and facilities for the cast and crew? We provide specialist set outs for catering teams, make up, and costume departments. Continental Event Hire (formerly Hirepool Event Hire) have a huge range of marquees to suit any requirement. We also provide flooring underfoot, side panel options such as windows or transparent walls, and even the essentials for cast and crew catering, such as plastic chairs and trestle tables, glassware, crockery, and cutlery. Our pedigree and knowledge of filming requirements is well established with previous work including: Avatar, Petes Dragon, The lion, the witch and the wardrobe, Narnia, and Mission Impossible. Contact our dedicated film industry specialist | Neil Bosman 027 204 6165 Auckland • Feilding • Nelson • Blenheim • Rangiora • Christchurch • Queenstown • Dunedin EDITORIAL CONTENTS GUILD NEWS & VIEWS Nau Mai! 2 Behind the scenes Haere Mai! Karla Rodgers looks back on a tumultuous year. In this issue, we say goodbye and salute one of the founders of the modern New Zealand film industry. Without 4 President’s rave Geoff, his many collaborators, and the sacrifices made by Annie Weston’s first column. And it’s a ripper. his family, there’s a very real chance that either you or I wouldn’t even be working in this business. -

Making Movies Then and Now – Still No I in Team TV Digital Changeover Hitting Our Airwaves Are We Actually Addicted to This Industry?

SUMMER 2012 | ISSUE 55 NZTECHOThe New Zealand Film and Video Technicians’ quarterly Making movies then and now – still no I in team TV digital changeover hitting our airwaves Are we actually addicted to this industry? www.nztecho.com Film experience that puts us in the picture... Elevated Work Platforms & Scaffold South Island Vehicle Rental North Island Vehicle Rental Portable Toilets & Showers a division of Marquee & Event Hire Generators & Pumps www.hirepool.co.nz For more information, contact: Film Specialists Tom Hotere 0272 614 195 or Craig McIntosh 0275 878 063 Rental Vehicles Marianne Dyer 0275 542 506 or Craig Booth 0274 919 027 Film experience that EDITORIAL CONTENTS It never fails to surprise me how much people do for free in this industry. GUILD NEWS & VIEWS I’m not just talking small budget projects and ‘one-offs’ for students or puts us in the picture... mates. It’s bigger than that. Actually, in many ways, ‘freebies’ keep the 2 Behind the scenes Executive officer Karla Rodgers – one year on! Techos’ Guild going. Ironic really when one of our core objectives is advocating for fair pay. 3 President’s rave Pres Alun ‘Albol’ Bollinger’ rounds off the year But it’s inspiring, those who willingly (and happily) put time and effort into pushing our Guild forward. Among those are our president, vice president, INDUSTRY Elevated Work Platforms & Scaffold executive committee and branch committees along with others in the indus- 6 Getting back to basics try, like some of the bigger production companies (you know who you are) Why good communication remains fundamental to filmmaking who give time, money and support. -

Vigil Study Guide

Written by TBA Directed by TBA This New Zealand Film Study Guide was written by Cynthia Thomas, who has 20 years' teaching experience. It has been designed as a starting point for teachers who wish to put together a unit based on Vigil. There are currently five New Zealand Film Study Guides available - An Angel At My Table, Forgotten Silver, Goodbye Pork Pie, Ngati, Sleeping Dogs. More titles are planned for 2003. To purchase a copy of these New Zealand movies, contact the distributor, Stage Door Video. Ph 64 9 378 8336 Fax 64 9 360 0819 Email [email protected] For more information on this and other NZ titles log onto WWW.NZFILM.CO.NZ Vigil was produced in ? A Film by Vincent Ward VIGIL • Featuring PENELOPE STEWART, FRANK WHITTEN, BILL KERR, FIONA KAY • Screenplay VINCENT WARD and study eight guide GRAEME TETLEY • Photography ALUN BOLLINGER • Production Designer KAI HAWKINS • Editor SIMON REECE • Music JACK BODY Executive Producer GARY HANNAM • Producer JOHN MAYNARD • Director VINCENT WARD • A JOHN MAYNARD PRODUCTION in association with The Film Investment Corporation of New Zealand and the New Zealand Film Commission 08 NEW ZEALAND FILM STUDY GUIDE The following are activities based on the achievement objectives presented in the Ministry of Education document, “English in the New Zealand Curriculum”. They may provide a starting point for teachers wishing to design a unit based on the film. NEW ZEALAND FILM STUDY GUIDE Vigil FOCUS PERSONAL reading PRESENTING “Vigil” was described in the Los Angeles Times as ‘a unique work by a major road to maturity, Toss has to cope with, and is confused about, many > Setting: Reading Film - View the sequence near the beginning of the talent’, and it has been variously described as ‘stunning’, ‘distinctive’, things. -

Taku Rakau E P R E S S K I T

TAKU RAKAU E P R E S S K I T A legacy … INTERNATIONAL SALES Chelsea Winstanley - StanStrong Ltd - PO Box 90957 - Auckland - NZ Tel +64 845 2954 - Mob +64 21 459745 - [email protected] PRODUCTION NOTES Writer/Director Kararaina Rangihau Producer Merata Mita Co-Producer Chelsea Winstanley Production Company StanStrong Ltd Country of production New Zealand Date of completion 2010 Shooting Format 35mm Screening Format HDCam/35mm Ratio 1:1.85 Duration 12.5 mins Genre Drama World Sales Chelsea Winstanley StanStrong Tel. 649 845 2954 [email protected] 35mm / Stereo / Colour / 12.5mins / 1:2.35 LOGLINE A child is enlightened when her grandmother explains the meaning of a waiata (song) that some have taken for granted. SHORT SYNOPSIS TAKU RAKAU E is a waiata tawhito composed about 1873 by Mihikitekapua of Tūhoe. Now in 2009, some generations later Mihikitekapua’s descendents continue to sing her waiata. In this short film Mihikitekapua laments the loss of land and her family succinctly phrased in a haunting lament. Erana, a young girl is learning Taku Rakau E at school. The school is set in a small rural village on the fringes of the Urewera. Take Rakau E is brought to life by nan who agrees to tell the story of Mihikitekapua to her great – grand – daugter, Erana. The pair drifts back and forth revisiting the times of the great chief Takahi and his warriors. Erena imagines, (sees), that Mihikitekapua searches in vain for Takahi and his people. She develops a strong sense of belonging as the story unfolds, and a new found pride in her tipuna – kuia. -

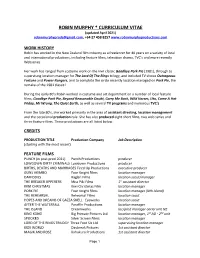

ROBIN MURPHY * CURRICULUM VITAE (Updated April 2021) [email protected], +64 27 458 8257

ROBIN MURPHY * CURRICULUM VITAE (updated April 2021) [email protected], +64 27 458 8257 www.robinmurphyproductions.com WORK HISTORY Robin has worked in the New Zealand film industry as a freelancer for 40 years on a variety of local and international productions, including feature films, television drama, TVC’s and more recently Webseries. Her work has ranged from costume work on the kiwi classic Goodbye Pork Pie (1981), through to supervising location manager for The Lord Of The Rings trilogy, and included TV shows Outrageous Fortune and Power Rangers, and to complete the circle recently location managed on Pork Pie, the remake of the 1981 classic! During the early 80’s Robin worked in costume and art department on a number of local feature films, Goodbye Pork Pie, Beyond Reasonable Doubt, Carry Me Back, Wild Horses, Utu, Came A Hot Friday, Mr Wrong, The Quiet Earth, as well as several TV programs and numerous TVC’s From the late 80’s, she worked primarily in the area of assistant directing, location management and the occasional production role. She has also produced eight short films, two web series and three feature films. These productions are all listed below. CREDITS PRODUCTION TITLE Production Company Job Description (starting with the most recent) FEATURE FILMS PUNCH (in post-prod 2021) Punch Productions producer LOWDOWN DIRTY CRIMINALS Lowdown Productions producer BIRTHS, DEATHS AND MARRIAGES Fired Up Productions executive producer GUNS AKIMBO Four Knight Films location manager DAFFODILS Raglan Films location scout/manager