MUSIC for the SILENT ONE: an Interview with Composer Jenny Mcleod

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ascent03opt.Pdf

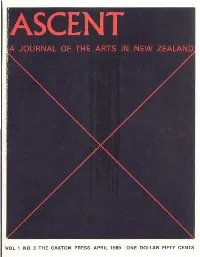

1.1.. :1... l...\0..!ll1¢. TJJILI. VOL 1 NO 3 THE CAXTON PRESS APRIL 1909 ONE DOLLAR FIFTY CENTS Ascent A JOURNAL OF THE ARTS IN NEW ZEALAND The Caxton Press CHRISTCHURCH NEW ZEALAND EDITED BY LEO BENSEM.AN.N AND BARBARA BROOKE 3 w-r‘ 1 Published and printed by the Caxton Press 113 Victoria Street Christchurch New Zealand : April 1969 Ascent. G O N T E N TS PAUL BEADLE: SCULPTOR Gil Docking LOVE PLUS ZEROINO LIMIT Mark Young 15 AFTER THE GALLERY Mark Young 21- THE GROUP SHOW, 1968 THE PERFORMING ARTS IN NEW ZEALAND: AN EXPLOSIVE KIND OF FASHION Mervyn Cull GOVERNMENT AND THE ARTS: THE NEXT TEN YEARS AND BEYOND Fred Turnovsky 34 MUSIC AND THE FUTURE P. Plat: 42 OLIVIA SPENCER BOWER 47 JOHN PANTING 56 MULTIPLE PRINTS RITA ANGUS 61 REVIEWS THE AUCKLAND SCENE Gordon H. Brown THE WELLINGTON SCENE Robyn Ormerod THE CHRISTCHURCH SCENE Peter Young G. T. Mofi'itt THE DUNEDIN SCENE M. G. Hire-hinge NEW ZEALAND ART Charles Breech AUGUSTUS EARLE IN NEW ZEALAND Don and Judith Binney REESE-“£32 REPRODUCTIONS Paul Beadle, 5-14: Ralph Hotere, 15-21: Ian Hutson, 22, 29: W. A. Sutton, 23: G. T. Mofiifi. 23, 29: John Coley, 24: Patrick Hanly, 25, 60: R. Gopas, 26: Richard Killeen, 26: Tom Taylor, 27: Ria Bancroft, 27: Quentin MacFarlane, 28: Olivia Spencer Bower, 29, 46-55: John Panting, 56: Robert Ellis, 57: Don Binney, 58: Gordon Walters, 59: Rita Angus, 61-63: Leo Narby, 65: Graham Brett, 66: John Ritchie, 68: David Armitage. 69: Michael Smither, 70: Robert Ellis, 71: Colin MoCahon, 72: Bronwyn Taylor, 77.: Derek Mitchell, 78: Rodney Newton-Broad, ‘78: Colin Loose, ‘79: Juliet Peter, 81: Ann Verdoourt, 81: James Greig, 82: Martin Beck, 82. -

Tony Barry) Goes Undercover Into a Retirement Village in a Last-Ditch Effort to Catch the One That Got Away, the Old Crook Frank (John

REST FOR THE WICKED ONE- SENTENCE SUMMARY: Old cop Murray (Tony Barry) goes undercover into a retirement village in a last-ditch effort to catch the one that got away, the old crook Frank (John Bach). SHORT SYNOPSIS Murray (Tony Barry) is a retired cop with a new undercover mission. He‟s going into a retirement village to catch Frank (John Bach), the old crook he has never been able to pin a crime on. Murray is convinced Frank murdered fellow crim, Jimmy Booth, years ago but was never able to make the evidence stick. This time, he‟s going to make sure he gets his man. So, when people in the retirement village start dying, Murray is on the case. But as events go increasingly haywire, it becomes apparent that all is not as it seems with Frank. Or Murray. 1 LONG SYNOPSIS Murray (Tony Barry), an old cop in reflective mood, cuts a story from the newspaper about an explosion at a P-house. Another old man on a mobility scooter, Frank (John Bach) arrives at a run-down house, takes the drug dealers inside by surprise, guns them all down and watches gleefully as the house blows up. Murray packs his bag, gets ready to leave, his daughter Susan (Sara Wiseman) fussing over him, helping him with his tie. Susan notices Murray has left the iron turn on. Murray tells his grandson Max (George Beca) he‟s off on a top-secret mission. Max seems worried. Murray describes himself as “an old dog off to dig up some old bones.” At Knightsbridge Gardens Retirement Village, Murray and Susan are greeted by the manager, Miss Pomeroy (Elisabeth Easther). -

Peter Britos

PETER BRITOS A Conversation with Merata Mita This conversation took place on January 15th 2003 at about 8pm in Honolulu. We met at Merata’s home offi ce near the campus where her youngest son Hepi is fi nishing up his high school studies. Hepi met me downstairs and escorted me to his mother’s study, where Merata was working on a book about her life experiences. PB: My mother once told me that the cool thing about talking is that sometimes you don’t know a thing existed until you say it. The mere physicality of the act brings you to a place that you couldn’t have gotten to any other way. MM: I’ve known things. And until I’ve articulated them, they’ve never been con- scious. I like the experience of new places and new things and working out how to survive in different environments that are totally dif- ferent ones than I’m used to. But until you articulate that survival, it’s just living. Geoff [Murphy—her producer/director husband] never sees those challenges as being pleas- ant. But I thrive on that sort of thing. In the end I had to agree with him that we should move from Los Angeles. But I didn’t know where, and didn’t really care. And he always had in his mind that the ideal halfway point between Los Angeles and New Zealand would be Hawai`i. So I said aah Polynesians, hmmm. Okay. So we ended up here and he could make whatever film he was making. -

This Action Thriller Futuristic Historic Romantic Black Comedy Will Redefine Cinema As We Know It

..... this action thriller futuristic historic romantic black comedy will redefine cinema as we know it ..... XX 200-6 KODAK X GOLD 200-6 OO 200-6 KODAK O 1 2 GOLD 200-6 science-fiction (The Quiet Earth) while because he's produced some of the Meet the Feebles, while Philip Ivey composer for both action (Pitch Black, but the leading lady for this film, to Temuera Morrison, Robbie Magasiva, graduated from standing-in for Xena beaches or Wellywood's close DIRECTOR also spending time working on sequels best films to come out of this country, COSTUME (Out of the Blue, No. 2) is just Daredevil) and drama (The Basketball give it a certain edginess, has to be Alan Dale, and Rena Owen, with Lucy to stunt-doubling for Kill Bill's The proximity to green and blue screens, Twenty years ago, this would have (Fortress 2, Under Siege 2) in but because he's so damn brilliant. Trelise Cooper, Karen Walker and beginning to carve out a career as a Diaries, Strange Days). His almost 90 Kerry Fox, who starred in Shallow Grave Lawless, the late great Kevin Smith Bride, even scoring a speaking role in but there really is no doubt that the been an extremely short list. This Hollywood. But his CV pales in The Lovely Bones? Once PJ's finished Denise L'Estrange-Corbet might production designer after working as credits, dating back to 1989 chiller with Ewan McGregor and will next be and Nathaniel Lees as playing- Quentin Tarantino's Death Proof. South Island's mix of mountains, vast comes down to what kind of film you comparison to Donaldson who has with them, they'll be bloody gorgeous! dominate the catwalks, but with an art director on The Lord of the Dead Calm, make him the go-to guy seen in New Zealand thriller The against-type baddies. -

DA Alin Weismann 03:09

Die Darstellung von Māori im Spielfilm. Die Bildung einer indigenen Identität anhand eines Massenmediums. DIPLOMARBEIT zur Erlangung des Magistergrades der Philosophie an der Fakultät für Human- und Sozialwissenschaften der Universität Wien eingereicht von Alin Weismann Wien, März 2009 1 Inhaltsverzeichnis 1. Vorwort............................................................................................................................................7 2. Einleitung........................................................................................................................................9 3. Einführung in die Geschichte Neuseelands................................................................................12 3.1 Neuseeland vor der Kolonisierung.............................................................................12 3.2 Die Entdeckung Neuseelands.....................................................................................13 3.2.1 Die erste europäische Besiedlung...............................................................................14 3.2.2 Treaty of Waitangi.......................................................................................................15 3.3.3 Auswirkungen der europäischen Besiedlung auf die gesellschaftliche Situation.......16 3.4 Wirtschaft und Regierungsform von damals bis heute...............................................17 3.5 Die Modernisierung Neuseelands...............................................................................19 3.6 Neuseelands Population -

Short Film Marketing Guide

SHORT FILM FESTIVAL MARKETING GUIDE 2021 Kia ora, welcome to Te Tumu Whakaata Taonga New Zealand Film Commission (NZFC) Short Film Festival Marketing Guide, designed to help with your most frequently asked festival related questions and to support you in planning a targeted release strategy for your short film. Wishing you the best of luck on your festival journey. Film Still: Ani (2019) – Written and directed by Josephine Stewart-Te Whiu (Ngāpuhi, Te Rarawa), produced by Sarah Cook Official Selection: Berlin International Film Festival ‘In Competition Generation Kplus’, Toronto International Film Festival, imagineNATIVE Film + Media Arts Festival, New Zealand International Film Festival, Rotorua Indigenous Film Festival, Vladivostok Pacific Meridian International Film Festival, Hamptons International Film Festival, Show Me Shorts Film Festival - Winner Best New Zealand Film Award, Best Cinematographer Award DISCLAIMER: This document is written as a guide only, intended for use by short film directors, writers and producers when referring to ‘you’, ‘your’ and ‘filmmakers’. Festival dates included in this guide are correct at publishing and subject to change. 1 © New Zealand Film Commission 2021 INDEX The First Steps – Preparing for Festival Success……………………………………………………………… 3 In Pre-Production………………………………………………………………………………………………. 3 In Production…………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 3 In Post-Production…………………………………………………………………………………………….. 4 At the Finish Line……………………………………………………………………………………………….. 4 Press Kit…………………………………………………………………………………………………. -

Craft New Zealand 45 Spring 1993

CONTENTS A MESSAGE TO READERS 2 LETTERS Graphics / Illustration In the fifteen months since Craft Photography 2 EDITORIAL NeWZea/andwas purchased from the Crafts Council of New Zealand, sales Jewellery 3 SPEAKING IN STONE have doubled and advertising is up. Unfortunately, the magazine still does Ceramics Wendy Laurenson spoke to Paul Ma— son about his development as an artist, not make a profit and the sharehold— Film / \fideo designer and maker. ers capital is exhausted. The immedi— CRAFTNew Zealand 6 SELF CONTAINED ate response of the directors of Craft Textiles Print Limited is to produce this ab- Issue 45, Spring I993 An emerging talent in the Hawkes Bay Print Joumalism breviated version. We hope to com- ISSN II70-9995 is jeweller/silversmith Tanya Zoe Robin- pensate subscribers for this by pro— Public Relations son. Roxanne Fea discusses her work. ducing a larger Yearbook issue in Publisher: December. This issue will focus on Advertising Craft Print Ltd, P O Box 1110 Nelson. Ph 03 548 3018, fax 03 548 8602. venues where fine craft and visual arts Television Broadcast Editor: may be seen or purchased. Peter Gibbs. Radio Broadcast The directors and shareholders are Editorial assistant committed to maintaining a magazine Media Management Julie Warren for craft. It may take a different form; Advertising sales: it must pay its way With your patience Performing Arts Peter Gibbs, ph 03 548 3018, fax 03 548 and support we'll continue the im— 8602. provements made so far. Rock Music Judy Wilson, ph 09 5766 340, fax 09 5347 526. Peter Gibbs, Editor Layout and art direction: Peter Gibbs. -

Nz Film Productions, 1990-2016

NZ FILM PRODUCTIONS, 1990-2016 PRODUCTION TITLE PRODUCERS SCRIPT DIRECTOR DOP PROD. DESIGNER COSTUME DESIGNER EDITOR SOUND DESIGNER 43,000 FEET * Feature 2012 Amber Easby Matt Harris Campbell Hooper Andrew Stroud Campbell Hooper Bruce Langley Heather Lee 800 WORDS * Teleseries 2015-2016 Chris Bailey James Griffin Mike Smith Fred Renata Gary Mackay Sarah Aldridge Eric De Beus John Holmes Maxine Fleming Pino Amenta Dave Garbett Greg Allison Paul Sutorius Kelly Martin Timothy Balme Michael Hurst Gary Hunt Julie McGauran Kate McDermott Murray Keane Chris Hampson Natalie Medlock Sarah-Kate Lynch 50 WAYS OF SAYING FABULOUS * Michele Fantl Stewart Main Stewart Main Simon Raby Ken Turner Kirsty Cameron Peter Roberts Peter Scholes Feature 2005 6 DAYS * Feauture 2016 Matthew Metcalfe Glenn Standring Toa Fraser Aaron Morton Liz McGregor Dan Kircher 7 DAYS * Teleseries 2009 Jon Bridges Josh Samuels Nigel Carpenter Luke Thompson Jason Pengelly A SONG OF GOOD * Feature 2008 Mark Foster Gregory King Gregory King Virginia Loane Ashley Turner Natalija Kucija Jonathan Venz ABANDONED * Telemovie 2014 Liz DiFiore Stephanie Johnson John Laing Grant McKinnon Roger Guise Jaindra Watson Margot Francis Mark Messenger ABERRATION * Feature 1997 Chris Brown Darrin Oura Tim Boxell Allen Guilford Grant Major Chris Elliott John Gilbert David Donaldson ABIOGENESIS * Feature 2012 Richard Mans Michelle Child AFTER THE WATERFALL * Feature Trevor Haysom Simone Horrocks Simone Horrocks Jac Fitzgerald Andy McLaren Kirsty Cameron Cushia Dillon Dick Reade 2010 ALEX * Feature -

Festivales DIAMANTES NEGROS

PARTICIPACION EN FESTIVALES DE DIAMANTES NEGROS (Dir: Miguel Alcantud) FECHA FESTIVAL PAIS 20-27 Abr 2013 Festival de Malaga de Cine Español España http://www.festivaldemalaga.com/ (Sección Oficial Largometrajes) 13-19 May 2013 Semana de Cine de Melilla España http://www.melilla.es/ (Muestra) 19-28 Jun 2013 Giffoni Film Festival Italia http://www.giffonifilmfestival.it/ (Generator +13) 22 Ago-2 Sep 2013 Festival des Films du Monde Montreal Canada http://www.ffm-montreal.org/ (Focus on World Cinema) 13-22 Sep 2013 Saint Petersburg International Film Festival Rusia http://festival-spb.ru/ (22 Frames) 25 Sep-6 Oct 2013 Raindance Film Festival Reino Unido http://www.raindance.org/ (International Feature) 25 Sep-10 Oct 2013 Festival Internacional de Cine Fine Arts Republica Dominca http://festivaldecinefinearts.com/ (Muestra) 27 Sep-6 Oct 2013 Cinespaña: Festival du Cinema Espagnol de Toulouse Francia http://www.cinespagnol.com/ (Panorama) 14-20 Oct 2013 Schlingel International Film Festival for Children and Young Audience Alemania http://www.ff-schlingel.de/ 18-22 Oct 2013 Giffoni Macedonia Macedonia http://www.giffonifilmfestival.it/ (Muestra) 23-26 Oct 2013 Giffoni Albania Albania http://www.giffonifilmfestival.it/ (Muestra) 8-16 Nov 2013 Festival de Cine Europeo de Sevilla España http://festivalcinesevilla.eu/ (Europa Junior) 8-16 Nov 2013 CineHorizontes Festival du Film Espagnol de Marseille Francia http://cinehorizontes.com/ 10-17 Nov 2013 Kolkata International Film Festival India http://kff.in/ (International Cinema) 13-19 Nov 2013 Muestra -

Tabla 1:Festivales Y Premios Cinematográficos

Tabla 1:Festivales y premios American Choreography Arts and Entertainment Critics cinematográficos Awards, USA Awards, Chile http://www.imdb.com/Sections/ American Cinema Editors, USA Artur Brauner Award Awards/Events American Cinema Foundation, Ashland Independent Film USA Festival American Cinematheque Gala Asia-Pacific Film Festival 2300 Plan 9 Tribute Asian American Arts 30th Parallel Film Festival American Comedy Awards, Foundation 7 d'Or Night USA Asian American International American Film Institute, USA Film Festival - A – American Independent Film Asianet Film Awards Festival Aspen Filmfest A.K.A. Shriekfest American Indian Film Festival Aspen Shortsfest ABC Cinematography Award American Movie Awards Association for Library Service ACTRA Awards American Screenwriters to Children AFI Awards, USA Association, USA Athens Film Festival, Georgia, AFI Fest American Society of USA AGON International Meeting of Cinematographers, USA Athens International Film Archaeological Film Amiens International Film Festival ALMA Awards Festival Athens International Film and AMPIA Awards Amnesty International Film Video Festival, Ohio, USA ARIA Music Awards Festival Athens Panorama of European ARPA International Film Amsterdam Fantastic Film Cinema Festival Festival Atlanta Film Festival ASCAP Film and Television Amsterdam International Atlantic City Film Festival Music Awards Documentary Film Festival Atlantic Film Festival ASIFA/East Animation Festival Anchorage International Film Atv Awards, Spain ATAS Foundation College Festival Aubagne International -

Iran, Pakistan Discuss Expansion of Media, Cultural Ties Italian Giffoni

Dec. 14, 2020 Seán O’Casey (Irish dramatist) All the world’s a stage and most of us are desperately unrehearsed. 12Arts & Culture License Holder: Islamic Republic News Agency (IRNA) Editor-in-Chief: Kambakhsh Khalaji Webinar to review coronavirus Editorial Dept. Tel: +98 21 88755761-2 Editorial Dept. Fax: +98 21 88761869 Subscription Dept. Tel: +98 21 88748800 consequences on Persian language ICPI Publisher: +98 21 88548892, 5 Advertising Dept. Tel & Email: +98 21 88500617 - [email protected] Website: www.irandailyonline.ir Arts & Culture Desk newspaper.irandaily.ir Email: [email protected] A two-day international webinar will be held from December Printing House: Iran Cultural & Press Institute 25-26 in Iran focusing on the consequences of the coronavirus outbreak on Persian language education and development. Address: Iran Cultural & Press Institute, #208 Khorramshahr Avenue Tehran-Iran Organized by the Sa’di Foundation and Allameh Tabataba’i Iran Daily has no responsibility whatsoever for the advertisements and promotional material printed in the newspaper. University, the webinar will host 30 Persian language instruc- tors to non-Persian speakers around the world, according to ISNA. Sistan and Baluchestan provinc- Head of Allameh Tabataba’i University, Hossein Salimi, es has long been the priority of the head of Sa’di Foundation, Gholam-Ali Haddad-Adel, Iran, Pakistan discuss expansion of Iran-Pakistan trade and cultural and a number of literary figures will attend the virtual pro- ties. gram. Apart from focusing on en- The -

GARY BASEMAN Education

GARY BASEMAN www.garybaseman.com Education: B.A. in Communications, University of California, Los Angeles, 1982 Phi Beta Kappa, Magna Cum Laude SELECTED SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2019 Imaginary Friends, Tauranga Art Gallery, New Zealand The Purr Room, The Other Art Fair, London, UK 2018 The Purr Room, The Other Art Fair Los Angeles, Santa Monica, CA 2015 My Eyes are Bigger than My Stomach, Drake One Fifty, Toronto, Canada HAPPY TOBY TO YOU! Hong Kong Times Square, Hong Kong, China Secret Society, Colette, Paris, France 2014 The Door is Always Open, Shanghai chi K11 Art Museum, Shanghai, China Mythical Homeland, Summerhall, Edinburgh, Scotland Play With Me, Or Else, Groove@CentralWorld, Bangkok, Thailand The Door is Always Open, Museum of Contemporary Art, Taipei, Taiwan 2013 Mythical Homeland, Aqua Art Fair, Miami, FL, December Mythical Homeland, Shulamit Gallery, Venice, CA The Door is Always Open, Skirball Cultural Center, Los Angeles, CA 2012 Nightmares of Halloween Past, KK Gallery, Los Angeles, CA Vicious, Antonio Colombo Arte Contemporanea, Milan, Italy The Omnipresent Toby, Innocean, Huntington Beach, CA 2011 Walking through Walls, Jonathan LeVine Gallery, New York, NY 2010 Dream Reality, Choque Cultural Gallery, Sao Paolo, Brazil Dream Reality, Southern Arkansas University, Magnolia, AR 2009 La Noche de la Fusión, Corey Helford Gallery, Culver City, CA Sacrificing of the Cake, Urbanix, Tel Aviv, Israel 2008 Knowledge Comes From Gas Release, Iguapop Gallery, Barcelona, Spain 2007 Hide and Seek in the Forest of ChouChou, Billy Shire Fine