Velociraptors at Midnight

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rhiannon Soulsby Song List

Rhiannon Soulsby Song List Played on Guitar A Team - Ed Sheeran Against all odds - Phil Collins All Of Me - John Legend Ave Maria - Beyonce Back to Black - Amy Winehouse Beautiful - Christina Aguilera Cecila - Simon and Garfunkel Don't Wanna Miss a thing - Aerosmith Flashlight - Jessie J Hallelujah - Alexandra Burke Hey Jude - The Beatles Hit me baby one more time - Britney Spears I can't help falling in love with you - Elvis Presley Jolene - Dolly Parton Killing me softly - The Fugees Kiss Me - Ed Sheeran Lego House - Ed Sheeran Little Things - One Direction Love Yourself - Justin Bieber Make you feel my love - Adele Me and My broken heart - Rixton Mr Brightside - The Killers Nina - Ed Sheeran/Nina Simone Mashup No - Meghan Trainor Over the rainbow - Eva Cassidy Please, Please, Please let me get what I want - The Smiths Price Tag/We Can't Stop - Miley Cyrus/ Jessie J mashup Rhiannon - Fleetwood Mac Riptide - Vance Joy She Moves in her own way - The Kooks Skinny Love - Bon Iver Skyfall - Adele Stay with me - Sam Smith The Chain - Ingrid Michaelson The Only Exception - Paramore There's a light that never goes out - The Smiths Thinking out loud - Ed Sheeran Thinking out loud - Ed Sheeran Wonderwall - Oasis Yesterday Today and Probably tomorrow - Courteeners Zombie - The Cranberries Performed with Backing Track At Last - Etta James I Know Where I've Been - Hairspray (Queen Latifah) Make you feel my love - Adele Read all about it - Emeli Sande Skyfall - Adele Titanium - Sia Valerie - Amy Winehouse and Mike Ronson . -

Grammy® Winners Fleetwood Mac to Be Honored As 2018 Musicares® Person of the Year at 28Th Annual Tribute

GRAMMY® WINNERS FLEETWOOD MAC TO BE HONORED AS 2018 MUSICARES® PERSON OF THE YEAR AT 28TH ANNUAL TRIBUTE Annual Gala Benefiting MusiCares® And Its Vital Safety Net Of Health And Human Services Programs For Music People Will Be Held At Radio City Music Hall During GRAMMY® Week On Friday, Jan. 26, 2018 SANTA MONICA, Calif. (July 19, 2017) — Two-time GRAMMY® winners Fleetwood Mac will be honored at the 2018 MusiCares® Person of the Year tribute on Friday, Jan. 26, 2018, it was announced today by Neil Portnow, President/CEO of the MusiCares Foundation® and the Recording Academy™. Proceeds from the 28th annual benefit gala—to be held at Radio City Music Hall in New York City during GRAMMY® Week two nights prior to the 60th Annual GRAMMY Awards®—will provide essential support for MusiCares (www.musicares.org), which ensures music people have a place to turn in times of financial, medical, and personal need. The evening's tribute chairs are Shelli and Irving Azoff, Dorothy and Martin Bandier, Kristin and James Dolan, and Anna Chapman and Ronald Perelman. Fleetwood Mac are being honored as the 2018 MusiCares Person of the Year in recognition of their significant creative accomplishments and their longtime support of a number of charitable causes, including MusiCares, the premier safety net of critical resources for the music industry. "Our 2018 MusiCares Person of the Year tribute is a celebration of firsts—the first time our annual signature gala will be held in New York City in 15 years, and the first time in the benefit's history that we will honor a band," said Portnow. -

THE COLLECTED POEMS of HENRIK IBSEN Translated by John Northam

1 THE COLLECTED POEMS OF HENRIK IBSEN Translated by John Northam 2 PREFACE With the exception of a relatively small number of pieces, Ibsen’s copious output as a poet has been little regarded, even in Norway. The English-reading public has been denied access to the whole corpus. That is regrettable, because in it can be traced interesting developments, in style, material and ideas related to the later prose works, and there are several poems, witty, moving, thought provoking, that are attractive in their own right. The earliest poems, written in Grimstad, where Ibsen worked as an assistant to the local apothecary, are what one would expect of a novice. Resignation, Doubt and Hope, Moonlight Voyage on the Sea are, as their titles suggest, exercises in the conventional, introverted melancholy of the unrecognised young poet. Moonlight Mood, To the Star express a yearning for the typically ethereal, unattainable beloved. In The Giant Oak and To Hungary Ibsen exhorts Norway and Hungary to resist the actual and immediate threat of Prussian aggression, but does so in the entirely conventional imagery of the heroic Viking past. From early on, however, signs begin to appear of a more personal and immediate engagement with real life. There is, for instance, a telling juxtaposition of two poems, each of them inspired by a female visitation. It is Over is undeviatingly an exercise in romantic glamour: the poet, wandering by moonlight mid the ruins of a great palace, is visited by the wraith of the noble lady once its occupant; whereupon the ruins are restored to their old splendour. -

CORE Sit-In Songs

- INDEX Certainly, Lord ••••••••••••••••••••••••••• Which Side Are You On.................... 2 Hallelujah, 11m A Traveling,,,,,,, •••••• •••• 3 Hold On • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 4 I Woke Up This Morning •• ,., ••• , ••• , •• , •• ,. 5 Do You Want Your Freedom , , • , , • , , , •• , , , • , • 6 I Know We 1 11 Meet Again ••• ••••• •••••••• •• • 7 How Did You Fee I ••• , •• , , , •• , • , , , , , , , •• , • • 8 Mi chae I Rowed The Boat Ashore , , , , , , , , , , • , • 9 We Sha II Overcome. , • , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , • • 10 We Sha II Not Be Moved , , , ...... , , , , , .. • • • • 11 Oh, Freedom ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 12 Freedom ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 13 Let My People Go,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,...... 14 Old Freedom Spirit, .. ,,, •• .. , .. , ... ,,...... 15 They Go WI I~, 16 Fight On .. , 17 Men Of The 18 I Wtlw 19 1 .. ·J· FOREWORD In th.is booklet you will find o number of the ·songs recorded in the a Ibum shown on the back cover. The singers on the record were participants in CORE's Freedom Highways project in the summer of 1962. Freedom Highways was designed to open chain restaurdnts along major federal highways to all persons. The other songs are some of those which have been favorites in the civi I rights movement North and South. The we 11-known writer 1 Nat Hentoff 1 said "The music which has emerged from these ex periences has restored the fiery art of American top ical song." fn his book The Folk Songs Of North America, Alan Lomax mentions of Negro slave songs that they "proclaimed that some day justice would triumph and that an end for sorrow and shame would come ••• " This, then, is what these songs are all about. As you and your friends "sing a long with CORE" we hope you wi II not only enjoy singing, but wi II also feel the vibrancy of the great movement for FREE DOM NOW. -

Lleetulood Mac Frumoars Any Drummer Looking for a Clear Example of What Playing for the Song Sounds and Feels Like Need Look No Further Than This Classic Album

lleetulood Mac frumoars Any drummer looking for a clear example of what playing for the song sounds and feels like need look no further than this classic album. I sk most pop fans about Fleetwood Fleetwood and bassist John McVie locking AMu.'t Rumours and you'll get an in and making mid-tempo magic. After earful about heartache, freshly splintered Fleetwood introduces the song with a tasty couples trying to salve raw wounds, snare-to-tom fill, he crashes on beat 2 and and kissing the past goodbye through the elements of a soft-rock classic-Nicks' song. But what ofthe heartbeat pulsing airy lead vocal, Christine McVie's Fender through that heartache, Mick Fleetwood's Rhodes, and Buckingham's sparse electric drumming? For all the praise heaped guitar-are assembled inside the deep upon the time-capsule-worthy songs that bass-and-drums pocket. lt's a seemingly Lindsey Buckingham, Christine McVie, simple concept, that "heartbeat" feel. and Stevie Nicks contributedto Rumours, But the Mac's founding fathers don't just Fleetwood's work doesn't get nearly the deliver it, they own it. lt's difficult to think love it deserves-at least outside the many of another rhythm section that plays it like producers, engineers, and musicians who thev do. have for decades been chasing down the In contrast to the carefully measured album's warm drum sound and impeccable oulse he lends to "Dreams," Fleetwood on tastefully dropped snare beats and a simple feel. Those studio rats and musos refer to "Go Your Own Way" is all primal kick, from but sweet combination of 16th notes during Fleetwood's playing on Rumours because the tom Datterns ofthe verses and solo the snare hits and cymbal crashes at 'l:59. -

The Midnight Library

Also by Matt Haig The Last Family in England The Dead Fathers Club The Possession of Mr Cave The Radleys The Humans Humans: An A-Z Reasons to Stay Alive How to Stop Time Notes on a Nervous Planet For Children The Runaway Troll Shadow Forest To Be A Cat Echo Boy A Boy Called Christmas The Girl Who Saved Christmas Father Christmas and Me The Truth Pixie The Truth Pixie Goes to School First published in Great Britain in 2020 by Canongate Books Ltd, 14 High Street, Edinburgh EH1 1TE canongate.co.uk This digital edition first published in 2020 by Canongate Books Copyright © Matt Haig, 2020 The right of Matt Haig to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 Excerpt from The Unabridged Journals of Sylvia Plath by Sylvia Plath, edited by Karen V. Kukil, copyright © 2000 by the Estate of Sylvia Plath. Used by permission of Anchor Books, an imprint of the Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC and Faber and Faber Ltd. All rights reserved. Excerpt from Marriage and Morals, Bertrand Russell Copyright © 1929. Reproduced by permission of Taylor & Francis Group. Every effort has been made to trace copyright holders and obtain their permission for the use of copyright material. The publisher apologises for any errors or omissions and would be grateful if notified of any corrections that should be incorporated in future reprints or editions of this book. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available on request from the British Library ISBN 978 1 78689 270 6 Export ISBN 978 1 78689 272 0 eISBN: 978 1 78689 271 3 To all the health workers. -

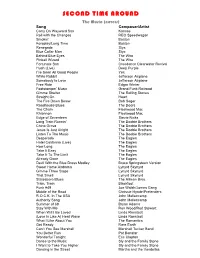

Second Time Around Second Time

SECOND TIME AROUND The Music (covers) Song Composer/Artist Carry On Wayward Son Kansas Roll with the Changes REO Speedwagon Smokin’ Boston Foreplay/Long Time Boston Renegade Styx Blue Collar Man Styx Behind Blue Eyes The Who Pinball Wizard The Who Fortunate Son Creedence Clearwater Revival Hush (Live) Deep Purple I’ve Seen All Good People Yes White Rabbit Jefferson Airplane Somebody to Love Jefferson Airplane Free Ride Edgar Winter Footstompin’ Music Grand Funk Railroad Gimme Shelter The Rolling Stones Straight On Heart The Fire Down Below Bob Seger Roadhouse Blues The Doors The Chain Fleetwood Mac Rhiannon Fleetwood Mac Edge of Seventeen Stevie Nicks Long Train Runnin’ The Doobie Brothers China Grove The Doobie Brothers Jesus Is Just Alright The Doobie Brothers Listen To The Music The Doobie Brothers Desperado The Eagles Hotel California (Live) The Eagles How Long The Eagles Take It Easy The Eagles Take It To The Limit The Eagles Already Gone The Eagles Devil With the Blue Dress Medley Bruce Springsteen Version Sweet Home Alabama Lynyrd Skynyrd Gimme Three Steps Lynyrd Skynyrd That Smell Lynyrd Skynyrd Statesboro Blues The Allman Bros. Train, Train Blackfoot Funk #49 Joe Walsh/James Gang Middle of the Road Chrissie Hynde/Pretenders R.O.C.K. In The USA John Mellencamp Authority Song John Mellencamp Summer of 69 Bryan Adams Stay With Me Ron Wood/Rod Stewart When Will I Be Loved Linda Ronstadt (Love Is Like A) Heat Wave Linda Ronstadt What I Like About You The Romantics Get Ready Rare Earth Can’t You See Marshall Marshall Tucker Band You Better Run Pat Benatar Wonderful Tonight Eric Clapton Dance to the Music Sly and the Family Stone I Want to Take You Higher Sly and the Family Stone Dancing in the Street Martha and the Vandellas .......and more . -

THE MIDNIGHT SUN by Rod Serling "The Secret of a Successful Artist,"

THE MIDNIGHT SUN by Rod Serling "The secret of a successful artist," an old instructor had told her years ago, "is not just to put paint on canvas--it is to transfer emotion, using oils and brush as a kind of nerve conduit." Norma Smith looked out of the window at the giant sun and then back to the canvas on the easel she had set up close to the window. She had tried to paint the sun and she had captured some of it physically--the vast yellow-white orb which seemed to cover half the sky. And already its imperfect edges could be defined. It was rimmed by massive flames in motion. This motion was on her canvas, but the heat--the incredible, broiling heat that came in waves and baked the city outside--could not be painted, nor could it be described. It bore no relation to any known quantity. It simply had no precedent. It was a prolonged, increasing, and deadening fever that traveled the streets like an invisible fire. The girl put the paint brush down and went slowly across the room to a small refrigerator. She got out a milk bottle full of water and carefully measured some into a glass. She took one swallow and felt its coolness move through her. For the past week just the simple act of drinking carried with it very special reactions. She couldn't remember actually feeling water before. Before, it had simply been thirst and then alleviation; but now the mere swallow of anything cool was an experience by itself. -

FLEETWOOD MAC: Die Legendären Klassiker Auf Farbigem Vinyl Fleetwood Mac , Rumours , Tusk , Mirage Und Tango in the Night

im Auftrag: medienAgentur Stefan Michel T 040-5149 1467 F 040-5149 1465 [email protected] FLEETWOOD MAC: Die legendären Klassiker auf farbigem Vinyl Fleetwood Mac , Rumours , Tusk , Mirage und Tango In The Night Ab 29. November über Rhino Limited Editions in individuell nummerierten Slipcases exklusiv über www.Rhino.com FLEETWOOD MAC „Rumours“ 4CD Edition bereits ab 8. November erhältlich! Zwischen 1975 und 1987 setzten FLEETWOOD MAC fünf einzigartige Multi-Platin-Alben in Folge in die Musiklandschaft – ein brillanter Coup, der sie zu einer der weltweit meistverkaufenden Bands in der Rockgeschichte machte! Am 29. November veröffentlicht Rhino diese fünf Klassiker auf Vinyl in jeweils eigener Farbe: Fleetwood Mac auf weißem Vinyl, Rumours auf transparentem Vinyl, Tusk als Doppel-LP auf silberfarbenem Vinyl, Mirage auf violettem Vinyl und Tango In The Night auf grünem Vinyl! Gleichzeitig erscheinen alle fünf Alben gesammelt in einem Slipcase als individuell durchnummerierte, auf 2.000 Exemplare limitierte Edition, die exklusiv über www.Rhino.com zu beziehen sein wird. Diese Sammlung kann ab sofort vorbestellt werden. Zuvor erscheint „Rumours“ am 8. November bereits als 4CD Box. Nach ihren bluesigen Anfängen erschienen FLEETWOOD MAC im Sommer 1975 in einer neuen Inkarnation in neuer Besetzung, die aus Mick Fleetwood, John McVie, Christine McVie und den neuen Mitgliedern Stevie Nicks und Lindsey Buckingham bestand. Ihr erstes gemeinsames Album, Fleetwood Mac (manchmal auch als The White Album bezeichnet), katapultierte sich umgehend auf Platz 1 der Billboard-Charts, hielt sich über ein Jahr in den Top- 40 und verkaufte sich mit Songs wie „Landslide“, „Say You Love Me“ und „Rhiannon“ allein in den USA über fünf Millionen Mal! 1977 warf die Band den Nachfolger Rumours ins Rennen, das vielfach als das beste Album aller Zeiten bewertet wird. -

The Glass Castle: a Memoir

The Glass Castle A Memoir Jeannette Walls SCRIBNER New York London Toronto Sydney Acknowledgments I©d like to thank my brother, Brian, for standing by me when we were growing up and while I wrote this. I©m also grateful to my mother for believing in art and truth and for supporting the idea of the book; to my brilliant and talented older sister, Lori, for coming around to it; and to my younger sister, Maureen, whom I will always love. And to my father, Rex S. Walls, for dreaming all those big dreams. Very special thanks also to my agent, Jennifer Rudolph Walsh, for her compassion, wit, tenacity, and enthusiastic support; to my editor, Nan Graham, for her keen sense of how much is enough and for caring so deeply; and to Alexis Gargagliano for her thoughtful and sensitive readings. My gratitude for their early and constant support goes to Jay and Betsy Taylor, Laurie Peck, Cynthia and David Young, Amy and Jim Scully, Ashley Pearson, Dan Mathews, Susan Watson, and Jessica Taylor and Alex Guerrios. I can never adequately thank my husband, John Taylor, who persuaded me it was time to tell my story and then pulled it out of me. Dark is a way and light is a place, Heaven that never was Nor will be ever is always true ÐDylan Thomas, "Poem on His Birthday" I A WOMAN ON THE STREET I WAS SITTING IN a taxi, wondering if I had overdressed for the evening, when I looked out the window and saw Mom rooting through a Dumpster. -

Rumours Ebook

RUMOURS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Freya North | 496 pages | 21 Jun 2012 | HarperCollins Publishers | 9780007326709 | English | London, United Kingdom Rumours PDF Book Saturday 27 June Monday 21 September December The third track on Rumours , "Never Going Back Again", began as "Brushes", a simple acoustic guitar tune played by Buckingham, with snare rolls by Fleetwood using brushes ; the band added vocals and further instrumental audio tracks to make it more layered. Here is a radio-friendly record about anger, recrimination, and loss. Monday 12 October Do you know the person or title these quotes desc Save Word. Retrieved 28 December Bundesverband Musikindustrie. Saturday 1 August Thursday 28 May Retrieved 23 July — via World Radio History. UK Albums Chart. Saturday 6 June Wednesday 2 September Largely recorded in California during , it was produced by the band with Ken Caillat and Richard Das… read more. Sunday 6 September By , 13 million copies of Rumours had been sold worldwide. Wednesday 23 September Sunday 26 July Tuesday 6 October The record often includes stressed drum sounds and distinctive percussion such as congas and maracas. Saturday 20 June Gold Dust Woman. Side two of Rumours begins with "The Chain", one of the record's most complicated compositions. The record's biggest hit single, " Rhiannon ", gave the band extensive radio exposure. All songs on Rumours concern personal, often troubled relationships. Stevie Nicks. The latter was the only classically trained musician in Fleetwood Mac, but both shared a similar sense of musicality. Wednesday 1 July The record contained each song of the original Rumours covered by a different act influenced by it. -

“Rumours”—Fleetwood Mac (1977) Added to the National Registry: 2017 Essay by Ken Caillat and Daniel Hoffheins (Guest Post)*

“Rumours”—Fleetwood Mac (1977) Added to the National Registry: 2017 Essay by Ken Caillat and Daniel Hoffheins (guest post)* Original album cover Original label Fleetwood Mac If you randomly sift through the music collection of most homes, you’ll more than likely find a copy of Fleetwood Mac’s “Rumours.” Like “Sgt. Pepper” before it, “Rumours” captured the mood of a generation, laid it down, and preserved it forever on vinyl. “Rumours” offered an unflinching look at the emotional fallout of free love, the anger of letting it go, and the optimism that comes from its survival. The message of infighting, pain, spectacle, and the excess of a star- crossed, storm-tossed band was delivered with a haunting and infectious mix of folk, pop, funk, blues, and hard rock. That mix was so potent and genuine that “Rumours” was an immediate hit, selling millions of copies and staying at number one in the album charts for over half a year. “Rumours” became the soundtrack for the charged era that spawned it, a phenomenon of unlikely forces converging to create a unique and addictively confessional work of art. Today, “Rumours” has sold over 40 million copies and continues to attract new listeners with each passing year, representing so completely its time that just its iconic album cover is enough to stand in for the lives, hopes, and heartaches of millions of Baby Boomers. The seventies were a paradoxical decade. The sexual revolution and the spirit of Woodstock were still the guiding lights of the Boomer revolution, but Vietnam and Watergate had sown massive despair and disillusionment in the country.