Lifting the Museum's Burden from the Backs of the University: Should The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Review Essay: Grappling with “Big Painting”: Akela Reason‟S Thomas Eakins and the Uses of History

Review Essay: Grappling with “Big Painting”: Akela Reason‟s Thomas Eakins and the Uses of History Adrienne Baxter Bell Marymount Manhattan College Thomas Eakins made news in the summer of 2010 when The New York Times ran an article on the restoration of his most famous painting, The Gross Clinic (1875), a work that formed the centerpiece of an exhibition aptly named “An Eakins Masterpiece Restored: Seeing „The Gross Clinic‟ Anew,” at the Philadelphia Museum of Art.1 The exhibition reminded viewers of the complexity and sheer gutsiness of Eakins‟s vision. On an oversized canvas, Eakins constructed a complex scene in an operating theater—the dramatic implications of that location fully intact—at Jefferson Medical College in Philadelphia. We witness the demanding work of the five-member surgical team of Dr. Samuel Gross, all of whom are deeply engaged in the process of removing dead tissue from the thigh bone of an etherized young man on an operating table. Rising above the hunched figures of his assistants, Dr. Gross pauses momentarily to describe an aspect of his work while his students dutifully observe him from their seats in the surrounding bleachers. Spotlights on Gross‟s bloodied, scalpel-wielding right hand and his unnaturally large head, crowned by a halo of wiry grey hair, clarify his mastery of both the vita activa and vita contemplativa. Gross‟s foil is the woman in black at the left, probably the patient‟s sclerotic mother, who recoils in horror from the operation and flings her left arm, with its talon-like fingers, over her violated gaze. -

The Gross Clinic, the Agnew Clinic, and the Listerian Revolution

Thomas Jefferson University Jefferson Digital Commons Department of Surgery Gibbon Society Historical Profiles Department of Surgery 11-1-2011 The Gross clinic, the Agnew clinic, and the Listerian revolution. Caitlyn M. Johnson, B.S. Thomas Jefferson University Charles J. Yeo, MD Thomas Jefferson University Pinckney J. Maxwell, IV, MD Thomas Jefferson University Follow this and additional works at: https://jdc.jefferson.edu/gibbonsocietyprofiles Part of the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine Commons, and the Surgery Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy Recommended Citation Johnson, B.S., Caitlyn M.; Yeo, MD, Charles J.; and Maxwell, IV, MD, Pinckney J., "The Gross clinic, the Agnew clinic, and the Listerian revolution." (2011). Department of Surgery Gibbon Society Historical Profiles. Paper 33. https://jdc.jefferson.edu/gibbonsocietyprofiles/33 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Jefferson Digital Commons. The Jefferson Digital Commons is a service of Thomas Jefferson University's Center for Teaching and Learning (CTL). The Commons is a showcase for Jefferson books and journals, peer-reviewed scholarly publications, unique historical collections from the University archives, and teaching tools. The Jefferson Digital Commons allows researchers and interested readers anywhere in the world to learn about and keep up to date with Jefferson scholarship. This article has been accepted for inclusion in Department of Surgery Gibbon Society Historical Profiles yb an authorized administrator of the Jefferson Digital Commons. For more information, please contact: [email protected]. Brief Reports Brief Reports should be submitted online to www.editorialmanager.com/ amsurg.(Seedetailsonlineunder‘‘Instructions for Authors’’.) They should be no more than 4 double-spaced pages with no Abstract or sub-headings, with a maximum of four (4) references. -

The Agnew Clinic, an 1889 Oil Painting by American Artist Thomas Eakins

Antisepsis and women in surgery 12 The Gross ClinicThe, byPharos Thomas/Winter Eakins, 2019 1875. Photo by Geoffrey Clements/Corbis/VCG via Getty Images The Agnew Clinic, an 1889 oil painting by American artist Thomas Eakins. Universal History Archive/UIG via Getty images Don K. Nakayama, MD, MBA Dr. Nakayama (AΩA, University of California, San Francisco, Los Angeles, 1986, Alumnus), emeritus professor of history 1977) is Professor, Department of Surgery, University of of medicine at Johns Hopkins, referring to Joseph Lister North Carolina School of Medicine, Chapel Hill, NC. (1827–1912), pioneer in the use of antiseptics in surgery. The interpretation fits so well that each surgeon risks he Gross Clinic (1875) and The Agnew Clinic (1889) being consigned to a period of surgery to which neither by Thomas Eakins (1844–1916) face each other in belongs; Samuel D. Gross (1805–1884), to the dark age of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, in a hall large surgery, patients screaming during operations performed TenoughT to accommodate the immense canvases. The sub- without anesthesia, and suffering slow, agonizing deaths dued lighting in the room emphasizes Eakins’s dramatic use from hospital gangrene, and D. Hayes Agnew (1818–1892), of light. The dark background and black frock coats worn by to the modern era of aseptic surgery. In truth, Gross the doctors in The Gross Clinic emphasize the illuminated was an innovator on the vanguard of surgical practice. head and blood-covered fingers of the surgeon, and a bleed- Agnew, as lead consultant in the care of President James ing gash in pale flesh, barely recognizable as a human thigh. -

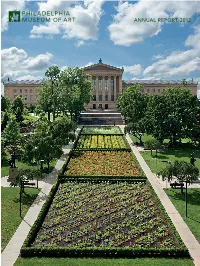

Annual Report 2012

BOARD OF TRUSTEES 4 LETTER FROM THE CHAIR 6 A YEAR AT THE MUSEUM 8 Collecting 10 Exhibiting 20 Teaching and Learning 30 Connecting and Collaborating 38 Building 44 Conserving 50 Supporting 54 Staffing and Volunteering 62 CALENDAR OF EXHIBITIONS AND EVENTS 68 FINANCIAL StATEMENTS 72 COMMIttEES OF THE BOARD OF TRUSTEES 78 SUPPORT GROUPS 80 VOLUNTEERS 83 MUSEUM StAFF 86 A REPORT LIKE THIS IS, IN ESSENCE, A SNAPSHOT. Like a snapshot it captures a moment in time, one that tells a compelling story that is rich in detail and resonates with meaning about the subject it represents. With this analogy in mind, we hope that as you read this account of our operations during fiscal year 2012 you will not only appreciate all that has been accomplished at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, but also see how this work has served to fulfill the mission of this institution through the continued development and care of our collection, the presentation of a broad range of exhibitions and programs, and the strengthening of our relationship to the com- munity through education and outreach. In this regard, continuity is vitally important. In other words, what the Museum was founded to do in 1876 is as essential today as it was then. Fostering the understanding and appreciation of the work of great artists and nurturing the spirit of creativity in all of us are enduring values without which we, individually and collectively, would be greatly diminished. If continuity—the responsibility for sustaining the things that we value most—is impor- tant, then so, too, is a commitment to change. -

0556 JN June Color

JUNE 1, 2002 Jeffwww.Jefferson.edu NEWS www.JeffersonHospital.org Jefferson Students Teach Underserved Children to Read University Honoring James Bagian, MD, dozen for 2001- Few would disagree that studying Class of 1977, at 178th Commencement 2002. The program and training to be a doctor or other complies with health professional is one very Jefferson’s 178th Annual Federal guidelines tough job. Let’s face it: many of us Commencement will be at 10:30 James P.Bagian, MD, JMC ’77 for work-study couldn’t do it. a.m., Friday, June 7, at the Kimmel funding. Dr. Bagian is well known to the That’s what makes so remarkable Center for the Performing Arts. Every Monday University President Paul C. Jefferson community and beyond the feat of an extraordinarily for his service as evening, several Brucker, MD, will deliver the committed dozen students from a NASA astro- students traveled to Jefferson Medical College (JMC) Convocation and confer all degrees. naut from 1980 Acts of the Apostles and the Jefferson College of Health Thomas J. Nasca, MD, FACP, to 1995. Church at 28th and Senior Vice President for Academic Professions (JCHP). He helped plan Master streets to Every Monday evening for the Affairs and Dean, Jefferson Medical and provide teach children from past academic year, members of the College (JMC), will present Doctor emergency med- 2 to 15 in the group broke from their studies to of Medicine degrees to 221 JMC ical and rescue church basement, spend time teaching young students. support for the site of a homeless underprivileged children at a North James S. -

View the 1967 Memory Book

MEMORIES MEMORIES MEMORIES MEMORIES NECROLOGY G. Thomas Balsbaugh Michael Z. Boris Stephen Byrne Vincent G. Caruso William M. Dellevigne Stephen M. Druckman Sheldon A. Friedman Daniel C. Harrer George H. Hughes Kenneth L. Kershbaum Charles H. Klieman William H. Labunetz Noreen March John H. Meloy Lloyd W. Moseley, Jr. Carl P. Mulveny Paul B. Silverman Anne Salmon Thompson Richard G. Traiman Jonathan Warren Matthew White Herbert S. Woldoff Alan H. Wolson Donald Leslie Adams 1967 IN REVIEW Top Pop Hits of 1967 I’m a Believer by The Monkees King of a Drag by The Buckinghams Ruby Tuesday by The Rolling Stones Love is Here And Now You’re Gone by The Supremes Penny Lane and The Beatles Happy Together by The Turtles Somethin’ Stupid by Nancy Sinatra and Frank Sinatra The Happening by The Supremes Groovin’ by The Young Rascals Respect by Aretha Franklin Windy by The Association Popular Films of 1967 Light My Fire by The Doors The Graduate All You Need is Love by The Beatles Bonnie and Clyde Ode to Billie Joe by Bobbie Gentry In the Heat of the Night The Letter by The Box Tops Cool Hand Luke To Sir With Love by Lulu The Dirty Dozen Incense And Peppermints by Strawberry Alarm Clock Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner Daydream Believer by The Monkees Barefoot in the Park Hello Goodbye by The Beatles Casino Royale Point Blank Camelot 1967 IN REVIEW In the News… The Vietnam War and protests continue The 25th Amendment to the constitution is ratified which deals with succession to the Presidency Interracial Marriage is declared constitutional by The Supreme Court in the "Loving v. -

THOMAS EAKINS: SCENES from MODERN LIFE Background

THOMAS EAKINS: SCENES FROM MODERN LIFE Background Information Background Information on Thomas Eakins During Eakins’ lifetime, the world experienced remarkable advances in science, industry, and technology. America was a place of new discoveries and new frontiers. Eakins embodied many of the ideals of the period, yet he collided with the moral boundaries of the Victorian era. In the end, Eakins was a brilliant, complicate painter whose ambitious drive towards his art and his visions of perfection left him scorned, disillusioned and alienated. Eakins was not a hero in his time, but his legacy and his impact on both the American art world and society far outlived those who condemned his art. He was an artist who strove to capture scenes from modern life at a time when modern life was evolving at a breathtaking pace. He established a tradition of portraiture that was both distinctly American and distinctly personal. He was an astute observer of the world around him, chronicling his family, friends, and his environment. He pioneered the use of photography in art-making and realized the merits and power the photograph as an art form in itself. His influence has grown dramatically since his death, and his works hand in galleries throughout the world. A Philadelphia native, Eakins graduated from Central High School for Boys, enrolled in drawing classes at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts and also took classes in anatomy at Jefferson Medical College (now Thomas Jefferson University). In 1866, Eakins became one of the first of four generations of American artists to travel to Europe for art training in the period between the end of the U.S. -

Let Them Sell Art: Why a Broader Deaccession Policy Today May

NOTES LET THEM SELL ART: WHY A BROADER DEACCESSION POLICY TODAY COULD SAVE MUSEUMS TOMORROW JORJA ACKERS CIRIGLIANA* I. INTRODUCTION In 1972, a New York Times critic unceremoniously introduced the public to deaccessioning when he outed the Metropolitan Museum of Art for selling art ―now that cash is hard for them to find.‖1 Since then, deaccessioning has become a widely implemented process that museums use to (1) remove a qualified object from the museum‘s collection record and (2) dispose of the object through sale, auction, gift, trade, or destruction.2 Despite wide implementation, there is currently a deaccessioning ―crisis‖3 that has instigated public outcry and even legislative reform.4 The crisis stems from the recent financial crisis, which has deeply affected museums. Museums are being forced to choose between making huge cut backs—even permanent closure—and deaccessioning portions of collections at the risk of lawsuits and condemnation. Museums should not have to choose. Instead, museums * Class of 2011, University of Southern California Gould School of Law; B.A. Art History and Theatre 2006, Knox College. The author wishes to thank Professor Scott Altman for his guidance and advice during the Note writing process, Professor Gregory Gilbert for an enthused introduction to the world of art, and the S. CAL. INTERDISC. L. J. staff and board members. 1 Prior to 1972, deaccessioning had gone largely unnoticed by the public. In that year, the Metropolitan Museum attempted to sell art from its collections as it had been doing quietly for the past twenty years. Stephen K. Urice, Deaccessioning: A Few Observations, ALI-ABA COURSE OF STUDY: LEGAL ISSUES IN MUSEUM ADMIN. -

The Salvation Project

DUKE UNIVERSITY English Department THE SALVATION PROJEC T T H E S ECULARIZATION OF C H R I S T I A N N ARRATIVES I N A M E R I C A N C A N C E R C ARE Jocelyn Streid Undergraduate Critical Honors Thesis Advisor: Dr. Priscilla Wald March 29, 2013 Acknowledgements After four years of college, I have realized that my education is best defined not by the classes I took or the papers I wrote or even the books I read, but by the people who have entered into my life. There are many for me to thank, and I’m going to be honest – I’m not really thanking them for the help they provided on this particular project, though for their tirelessness I am eternally grateful. Rather, I thank them for the ways in which their mentorship has turned me into the sort of student who can write a thesis in the first place. I only ask that for once they please lay aside their humility and grant me the privilege of singing their praises. Neither this thesis, nor the theology that lies behind it, would have come into being without Dr. Raymond Barfield of both the Divinity School and the Medical School. He entertained me when I showed up in his office three years ago with the vague idea that I was interested in medicine and narrative and God, and has continued to entertain ever since. Ray has left his fingerprints on many who pass through this university, and I am no exception. -

Thomas Eakins: Scenes from Modern Life

THOMAS EAKINS: SCENES FROM MODERN LIFE Lesson 3: On Being Different Estimated Time: 3 sessions (Within 45 minutes) Introduction “He was defiant. He was inflexible. He was self-righteous. He was undiplomatic and inconsiderate. He was never boring.” Opening narration from Thomas Eakins: Scenes From Modern Life This lesson plan explores the life of Thomas Eakins who was considered “an original in a conventional society.” By observing and reflecting on the life and art of Thomas Eakins, students will draw correlations between their own ideas of being different, their school environment, the determination to pursue goals and Thomas Eakins’ life. The lesson utilizes the entire documentary film Thomas Eakins: Scenes From Modern Life, and is shown in three separate sessions. Grade Level 9-12 Please Note: The video program contains several scenes featuring black and white archival photographs of nude male and female models, including some photographs of Eakins himself. These scenes are noted in the lesson plan. Subject Area(s) American History Art History Social Studies Language Arts Objectives • Students will synthesize ideas about societal norms in the 1880s and current day • Students will demonstrate understanding of Thomas Eakins art and life events through verbal discussion • Students will compile and present ideas in written form • Students will engage in a writing process of note taking, 1st drafts and final editing Estimated Time 3 sessions (Within 45 minutes) Materials • VHS or DVD-Thomas Eakins: Scenes From Modern Life • VHS or DVD Player and TV monitor • Student file folders for writing assignments Procedure Session 1-Introducing Thomas Eakins (45 minutes) In this session you will introduce the project and Thomas Eakins as an artist. -

The Issue of Realism in Raphael Soyer's Artist Portraits, My Friends and the Homage to Thomas Eakins

The issue of realism in Raphael Soyer's artist portraits, My friends and the Homage to Thomas Eakins Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Hughes, Betsy Ann O'Brien, 1952- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 28/09/2021 17:05:27 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/558138 THE ISSUE OF REALISM IN RAPHAEL SOYER'S ARTIST PORTRAITS, MY FRIENDS AND THE HOMAGE TO THOMAS EAKINS by- Betsy Ann O'Brien Hughes Copyright ® Betsy Ann O 1Brien Hughes A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF ART In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS with a Major in Art History In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 1990 2 STATEMENT BY THE AUTHOR This thesis has been submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for an advanced degree at The University of Arizona and is deposited in the University Library to be made available to borrowers under rules of the Library. Brief quotations from this thesis are allowable without special permission,^ provided that accurate acknowledgment of source is made. Requests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this manuscript in whole or in part may be granted by the copyright holder. SIGNED; f APPROVAL BY THESIS DIRECTOR This thesis has been approved on the date shown below; Sheldon Reich Professor of Art History 3 ' ' ■: " ' . -

In This Painting by Thomas Eakins, Dr. Samuel D. Gross Appears I

PORTRAIT OF DR. SAMUEL D. GROSS (THE GROSS CLINIC) In this painting by Thomas Eakins, Dr. Samuel D. Gross appears in the surgical amphitheater at Philadelphia’s Jefferson Medical College (now part of Thomas Jefferson University), illuminated by the skylight overhead. Five doctors (one of whom is obscured by Dr. Gross) attend to the young patient, whose left thigh, bony buttocks, and 1875 Oil on canvas sock-clad feet are all that is visible to the viewer. Chief of Clinic Dr. 8 feet x 6 feet 6 inches (243.8 x 198.1 cm) James M. Barton bends over the patient, probing the incision, while THOMAS EAKINS junior assistant Dr. Charles S. Briggs grips the patient’s legs and American Dr. Daniel M. Appel keeps the incision open with a retractor. The Gift of the Alumni Association to Jefferson Medical College in 1878 and purchased by anesthetist (Dr. W. Joseph Hearn) holds a folded napkin soaked with the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts and the Philadelphia Museum of Art in 2007 with the generous support of more than chloroform over the patient’s face, while the clinic clerk (Dr. Franklin 3,600 donors, 2007, 2007-1-1 West) records the proceedings. A woman at the left, traditionally identified as the patient’s mother, cringes and shields her eyes, LET’S LOOK unable to look. Confident of the outcome of the operation, Dr. Gross What is happening in this picture? What is everyone doing? calmly and majestically turns to address his students, including the intent figure of Thomas Eakins, who is seated at the right edge of What areas catch your eye? What made you look there? the canvas.