The Salvation Project

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CW23 Complete-Issue.Pdf

C a n c e r W o r l d 2 3 Education & knowledge through people & facts M A R Number 23, March-April 2008 C H - A P R I L 2 0 0 8 Giovanni Paganelli § Giovanni Paganelli: nuclear medicine’s enthusiastic ambassador § Personalised therapies: who will champion the needs of patients? § Scientific integrity must come first: the unique Baum brand of passion and perversity § Helping survivors get thei r lives back Best Reporter Make prevention easy Czech journalist and colon cancer survivor pens a message to her country’s health professionals Had Iva Skochová been in her native Prague rather than New York when she went to the doctor complaining of stomach pains, her colon cancer may never have been discovered in time. A staff writer on the Prague Post , Skochová won a Best Cancer Reporter Award for a piece she wrote about the lessons to be learned from her experience, which is republished below. t is no secret that the polyps before they turn Czech Republic has the cancerous or at least in the Iworld’s highest colon can - early stages of cancer, before cer rates per capita: every year they metastasise, it sharply 7,500 new patients are diag - decreases the premature mor - nosed, and every day 16 peo - tality of patients. ple die from it. Colonoscopies in the Anyone who has sampled Czech Republic, however, traditional Czech food will be are usually performed only tempted to jump to conclu - when patients already show sions and say “no wonder”. On symptoms of colon cancer average, Czechs consume (indigestion, abdominal pain, excessive amounts of animal anaemia, etc), not as a form of fats and cured meats and pre - prevention. -

Presidential Address “Barber Poles

Barber Poles, Battlefields, and Wounds That Will Not Heal Robert M. Byers, MD, Houston, Texas aving grown up playing baseball in a small town in became a despised and neglected practice. Much of this has Maryland, I was always reminded of the four base- been blamed on the church, which prohibited the practice H ball Hall of Famers who lived there: Babe Ruth, “Ecclesia abhorret a sanguine,” which means the church whom you might have heard of; Jlmmy Fox; Lefty Grove; abhors the “shedding of blood.” As civilization regained its Al Kaline; and, a future Hall of Famer, Cal Ripkin Jr., who hold upon the people, surgery revived. The most notable just broke the record for consecutive games played. I, too, and significant exception during this era was in the arena dreamed of some day playing in the Major Leagues. I didn’t of the battlefield. Surgery prospered with the bloody strife make it in baseball, but I certainly have played in the big of men, medicine did not.’ The barber’s identification with leagues of academic surgery w-ith the likes of Jay Ballantyne war produced the characteristic colors wrapped around a and Dick Jesse. For this, I am extremely privileged and pole: red for blood and white for bandages. Battlefield sur- grateful. gery was brutal, but so were the radical procedures per- I have chosen “Barber Poles, Battlefields, and Wounds formed by surgeons in the early 1900s to treat cancer. that Won’t Heal” as the title of my Presidential Address. Hippocrates said “war is the only proper school of the This reflects a personal flavor and, perhaps, requires a brief surgeon. -

Review Essay: Grappling with “Big Painting”: Akela Reason‟S Thomas Eakins and the Uses of History

Review Essay: Grappling with “Big Painting”: Akela Reason‟s Thomas Eakins and the Uses of History Adrienne Baxter Bell Marymount Manhattan College Thomas Eakins made news in the summer of 2010 when The New York Times ran an article on the restoration of his most famous painting, The Gross Clinic (1875), a work that formed the centerpiece of an exhibition aptly named “An Eakins Masterpiece Restored: Seeing „The Gross Clinic‟ Anew,” at the Philadelphia Museum of Art.1 The exhibition reminded viewers of the complexity and sheer gutsiness of Eakins‟s vision. On an oversized canvas, Eakins constructed a complex scene in an operating theater—the dramatic implications of that location fully intact—at Jefferson Medical College in Philadelphia. We witness the demanding work of the five-member surgical team of Dr. Samuel Gross, all of whom are deeply engaged in the process of removing dead tissue from the thigh bone of an etherized young man on an operating table. Rising above the hunched figures of his assistants, Dr. Gross pauses momentarily to describe an aspect of his work while his students dutifully observe him from their seats in the surrounding bleachers. Spotlights on Gross‟s bloodied, scalpel-wielding right hand and his unnaturally large head, crowned by a halo of wiry grey hair, clarify his mastery of both the vita activa and vita contemplativa. Gross‟s foil is the woman in black at the left, probably the patient‟s sclerotic mother, who recoils in horror from the operation and flings her left arm, with its talon-like fingers, over her violated gaze. -

The Gross Clinic, the Agnew Clinic, and the Listerian Revolution

Thomas Jefferson University Jefferson Digital Commons Department of Surgery Gibbon Society Historical Profiles Department of Surgery 11-1-2011 The Gross clinic, the Agnew clinic, and the Listerian revolution. Caitlyn M. Johnson, B.S. Thomas Jefferson University Charles J. Yeo, MD Thomas Jefferson University Pinckney J. Maxwell, IV, MD Thomas Jefferson University Follow this and additional works at: https://jdc.jefferson.edu/gibbonsocietyprofiles Part of the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine Commons, and the Surgery Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy Recommended Citation Johnson, B.S., Caitlyn M.; Yeo, MD, Charles J.; and Maxwell, IV, MD, Pinckney J., "The Gross clinic, the Agnew clinic, and the Listerian revolution." (2011). Department of Surgery Gibbon Society Historical Profiles. Paper 33. https://jdc.jefferson.edu/gibbonsocietyprofiles/33 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Jefferson Digital Commons. The Jefferson Digital Commons is a service of Thomas Jefferson University's Center for Teaching and Learning (CTL). The Commons is a showcase for Jefferson books and journals, peer-reviewed scholarly publications, unique historical collections from the University archives, and teaching tools. The Jefferson Digital Commons allows researchers and interested readers anywhere in the world to learn about and keep up to date with Jefferson scholarship. This article has been accepted for inclusion in Department of Surgery Gibbon Society Historical Profiles yb an authorized administrator of the Jefferson Digital Commons. For more information, please contact: [email protected]. Brief Reports Brief Reports should be submitted online to www.editorialmanager.com/ amsurg.(Seedetailsonlineunder‘‘Instructions for Authors’’.) They should be no more than 4 double-spaced pages with no Abstract or sub-headings, with a maximum of four (4) references. -

The Secret History of the War on Cancer

Book review The secret history of the war on cancer Devra Davis Basic Books. New York, New York, USA. 2007. 528 pp. $27.95. ISBN: 978-0465015665 (hardcover). Reviewed by Raymond N. DuBois The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, Texas, USA. E-mail: [email protected] In 2007, the American Cancer Society were never fully appreciated by the public. exposed to complex mixtures of these agents, reported 12 million new cancer cases world- Still, they weren’t necessarily kept secret. The yet testing is done on one chemical at a time. wide and 7.6 million cancer deaths. Given issues become confused as she bounces from These combinations, at low levels, may be far these staggering numbers, it’s no wonder that one to another, in no perceivable order, vent- more dangerous than exposure to a higher people are beginning to question why the ing outrage. For example, she describes the concentration of one agent alone. War on Cancer, declared by President Nixon human experimentation performed in Nazi One of the greatest unpreventable risk fac- in 1971, has not led to the elimination of this Germany that indicated a clear connection tors for cancer is age. With the tidal wave of disease. Epidemiologist Devra Davis, director between tobacco exposure and cancer. How- baby boomers fast approaching retirement of the Center for Environmental Oncology at ever, she deadens her point by expounding age, we will definitely see many more cases of the University of Pittsburgh Cancer Institute on the numerous other atrocities carried out cancer over the next few decades. -

The Agnew Clinic, an 1889 Oil Painting by American Artist Thomas Eakins

Antisepsis and women in surgery 12 The Gross ClinicThe, byPharos Thomas/Winter Eakins, 2019 1875. Photo by Geoffrey Clements/Corbis/VCG via Getty Images The Agnew Clinic, an 1889 oil painting by American artist Thomas Eakins. Universal History Archive/UIG via Getty images Don K. Nakayama, MD, MBA Dr. Nakayama (AΩA, University of California, San Francisco, Los Angeles, 1986, Alumnus), emeritus professor of history 1977) is Professor, Department of Surgery, University of of medicine at Johns Hopkins, referring to Joseph Lister North Carolina School of Medicine, Chapel Hill, NC. (1827–1912), pioneer in the use of antiseptics in surgery. The interpretation fits so well that each surgeon risks he Gross Clinic (1875) and The Agnew Clinic (1889) being consigned to a period of surgery to which neither by Thomas Eakins (1844–1916) face each other in belongs; Samuel D. Gross (1805–1884), to the dark age of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, in a hall large surgery, patients screaming during operations performed TenoughT to accommodate the immense canvases. The sub- without anesthesia, and suffering slow, agonizing deaths dued lighting in the room emphasizes Eakins’s dramatic use from hospital gangrene, and D. Hayes Agnew (1818–1892), of light. The dark background and black frock coats worn by to the modern era of aseptic surgery. In truth, Gross the doctors in The Gross Clinic emphasize the illuminated was an innovator on the vanguard of surgical practice. head and blood-covered fingers of the surgeon, and a bleed- Agnew, as lead consultant in the care of President James ing gash in pale flesh, barely recognizable as a human thigh. -

The War on Cancer—Shifting from Disappointment to New Hope

Ann Surg Oncol (2010) 17:1971–1978 DOI 10.1245/s10434-010-0987-2 ORIGINAL ARTICLE – TRANSLATIONAL RESEARCH AND BIOMARKERS Society of Surgical Oncology Presidential Address: The War on Cancer—Shifting from Disappointment to New Hope William G. Cance, MD Department of Surgical Oncology, Roswell Park Cancer Institute, Buffalo, NY First of all, it has been a singular honor to be your President for the past year. It has been a wonderful journey with the SSO since I first began working on the Program Committee in 1993. I have learned from outstanding mentors during this time and have watched our Society grow not only in membership, but also redefining itself as we seek to broaden our outreach across all surgeons across the world. We keep getting better and I am confident that our organization will continue on the paths set by my predecessors. From a personal standpoint, I am grateful to all of the people who have helped me get here. The list is too large to show, and of course I would forget some, but I do want to thank a number of people who have guided me along the way. Dr. Warren Cole was my earliest mentor—meeting him in high school and benefiting from his wise counsel until his death in 1990 (Fig. 1). He was not only a con- summate surgical oncologist who happened to retire to my hometown, but was a visionary, frank mentor. Early in my career, Dr. Hilliard Seigler helped nurture a lifelong love of FIG. 1 Dr. Warren Cole the laboratory and was my first real-life demonstration of a surgical scientist. -

Springer International Publishing AG, Part of Springer Nature 2018 1 M

Biomedicine and Its Historiography: A Systematic Review Nicolas Rasmussen Contents Introduction ....................................................................................... 1 What Is Biomedicine? ............................................................................ 2 Biomedicine’s Postwar Development ............................................................ 7 The Distribution of Activity in Biomedicine and in Its Historiography . ...................... 14 Conclusion ........................................................................................ 19 References ........................................................................................ 20 Abstract In this essay I conduct a quantitative systematic review of the scholarly literature in history of life sciences, assessing how well the distribution of the activity of historians aligns with the distribution of activities of scientists across fields of biomedical research as defined by expenditures by the cognate institutes of the United States NIH. I also ask how well the distribution of resources to the various research fields of biomedicine in the second half of the 20th Century has aligned with morbidity and mortality in the United States associated with the cognate disease categories. The two exercises point to underexplored areas for historical work, and open new historical questions about research policy in the US. Introduction I have taken an unusual approach in this essay to ask a question that, to my knowledge, has not been addressed before: how -

The Secret History of the War on Cancer

The secret history of the war on cancer Raymond N. DuBois J Clin Invest. 2008;118(6):1978-1978. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI36051. Book Review In 2007, the American Cancer Society reported 12 million new cancer cases worldwide and 7.6 million cancer deaths. Given these staggering numbers, it’s no wonder that people are beginning to question why the War on Cancer, declared by President Nixon in 1971, has not led to the elimination of this disease. Epidemiologist Devra Davis, director of the Center for Environmental Oncology at the University of Pittsburgh Cancer Institute and an environmental advisor to Newsweek, argues in her new book, The secret history of the war on cancer, that this effort has not focused on the “right” battles. She insists that progress has been lost as governments placate and cover up for industries that pollute and contaminate the environment with carcinogens and that more attention should be focused on environmental risks for this disease, such as tobacco use, alcohol consumption, and workplace carcinogen exposure. This is familiar territory for Davis. Her previous book, When smoke ran like water (1), a 2002 finalist for the National Book Award for Nonfiction, documented the relationship between air pollution and a host of human diseases. In this new release, she concentrates on cancer as a by-product of industry greed and governmental negligence. As a cancer researcher myself, I found the book to be informative and interesting, but the title is a misnomer. Most of the […] Find the latest version: https://jci.me/36051/pdf Book review The secret history of the war on cancer Devra Davis Basic Books. -

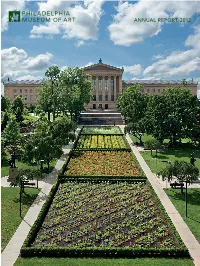

Annual Report 2012

BOARD OF TRUSTEES 4 LETTER FROM THE CHAIR 6 A YEAR AT THE MUSEUM 8 Collecting 10 Exhibiting 20 Teaching and Learning 30 Connecting and Collaborating 38 Building 44 Conserving 50 Supporting 54 Staffing and Volunteering 62 CALENDAR OF EXHIBITIONS AND EVENTS 68 FINANCIAL StATEMENTS 72 COMMIttEES OF THE BOARD OF TRUSTEES 78 SUPPORT GROUPS 80 VOLUNTEERS 83 MUSEUM StAFF 86 A REPORT LIKE THIS IS, IN ESSENCE, A SNAPSHOT. Like a snapshot it captures a moment in time, one that tells a compelling story that is rich in detail and resonates with meaning about the subject it represents. With this analogy in mind, we hope that as you read this account of our operations during fiscal year 2012 you will not only appreciate all that has been accomplished at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, but also see how this work has served to fulfill the mission of this institution through the continued development and care of our collection, the presentation of a broad range of exhibitions and programs, and the strengthening of our relationship to the com- munity through education and outreach. In this regard, continuity is vitally important. In other words, what the Museum was founded to do in 1876 is as essential today as it was then. Fostering the understanding and appreciation of the work of great artists and nurturing the spirit of creativity in all of us are enduring values without which we, individually and collectively, would be greatly diminished. If continuity—the responsibility for sustaining the things that we value most—is impor- tant, then so, too, is a commitment to change. -

Bounds in Competing Risks Models and the War on Cancer∗

Bounds in Competing Risks Models and the War on Cancer∗ Bo E. Honor´e† Adriana Lleras-Muney‡ This Version: October 2005 Abstract In 1971 President Nixon declared war on cancer. Thirty years later, many have declared the war a failure: the age-adjusted mortality rate from cancer in 2000 was essentially the same as in the early 1970s. Meanwhile the age-adjusted mortality rate from cardiovascular disease fell dramatically. Since the causes underlying cancer and cardiovascular disease are likely to be correlated, the decline in mortality rates from cardiovascular disease may in part explain the lack of progress in cancer mortality. Because competing risks models (used to model mortality from multiple causes) are fundamentally unidentified, it is difficult to get a clear picture of the trends in cancer. This paper derives bounds for aspects of the underlying distributions under a number of different assumptions. Most importantly, we do not assume that the underlying risks are independent, and impose weak parametric assumptions in order to obtain identification. We provide a framework to estimate competing risk models with interval outcome data and discrete explanatory variables, both of which are common in empirical applications. We use our method to estimate changes in cancer and cardiovascular mortality since 1970. The estimated bounds for the effect of time on the duration until death for either cause are fairly tight and suggest much larger improvements in cancer than previously estimated. Keywords: Bounds, Competing Risks, Cancer, Cardiovascular. JEL Classification: I10, C40. ∗We would like to thank Jaap Abbring, Josh Angrist, Eric J. Feuer, Marco Manacorda, researchers at the National Cancer Institute, and seminar participants at CAM at the University of Copenhagen, London School of Economics, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, NBER Summer Institute, Princeton University, University College London, and the Harvard–MIT–Boston University Health seminar for their suggestions. -

0556 JN June Color

JUNE 1, 2002 Jeffwww.Jefferson.edu NEWS www.JeffersonHospital.org Jefferson Students Teach Underserved Children to Read University Honoring James Bagian, MD, dozen for 2001- Few would disagree that studying Class of 1977, at 178th Commencement 2002. The program and training to be a doctor or other complies with health professional is one very Jefferson’s 178th Annual Federal guidelines tough job. Let’s face it: many of us Commencement will be at 10:30 James P.Bagian, MD, JMC ’77 for work-study couldn’t do it. a.m., Friday, June 7, at the Kimmel funding. Dr. Bagian is well known to the That’s what makes so remarkable Center for the Performing Arts. Every Monday University President Paul C. Jefferson community and beyond the feat of an extraordinarily for his service as evening, several Brucker, MD, will deliver the committed dozen students from a NASA astro- students traveled to Jefferson Medical College (JMC) Convocation and confer all degrees. naut from 1980 Acts of the Apostles and the Jefferson College of Health Thomas J. Nasca, MD, FACP, to 1995. Church at 28th and Senior Vice President for Academic Professions (JCHP). He helped plan Master streets to Every Monday evening for the Affairs and Dean, Jefferson Medical and provide teach children from past academic year, members of the College (JMC), will present Doctor emergency med- 2 to 15 in the group broke from their studies to of Medicine degrees to 221 JMC ical and rescue church basement, spend time teaching young students. support for the site of a homeless underprivileged children at a North James S.