The Quilt Index: from Preservation and Access to Co-Creation of Knowledge

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Godey Quilt: One Woman’S Dream Becomes a Reality Sandra L

Western Kentucky University TopSCHOLAR® DLSC Faculty Publications Library Special Collections 2016 The Godey Quilt: One Woman’s Dream Becomes a Reality Sandra L. Staebell Western Kentucky University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wku.edu/dlsc_fac_pub Part of the Fiber, Textile, and Weaving Arts Commons Recommended Citation Sandy Staebell, “The Godey Quilt: One Woman’s Dream Becomes a Reality,” Uncoverings 2016, Volume 37, American Quilt Study Group, edited by Lynne Zacek Bassett, copyright 2016, pp. 100-134, Color Plates 8-11 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by TopSCHOLAR®. It has been accepted for inclusion in DLSC Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of TopSCHOLAR®. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Godey Quilt: One Woman’s Dream Becomes a Reality Sandra Staebell The Godey Quilt is a 1930s appliqué quilt composed of fifteen fabric portraits of men and women clothed in fashionable mid-nineteenth century attire. The dream of Mildred Potter Lissauer (1897−1998) of Louisville, Kentucky, this textile is a largely original design that is not representative of the majority of American quilts made during the early 1930s. Notable for the beauty and quality of its workmanship, the quilt’s crafting was, in part, a response to the competitive spirit that reigned in quiltmaking at the time. Significantly, the survival of the materials that document its conception, design, and construction enhances its significance and can be used to create a timeline of its creation. Reflecting Colonial Revival concepts and imagery, the Godey Quilt is a remarkable physical expression of that era. -

The Jane Gordon Quilt by WILLIAM and CHARLENE STEPHENS

Issue 147 Winter 2020-2021 News Publication of the American Quilt Study Group v IN THIS ISSUE The Value of Revisiting Research: The Jane Gordon Quilt BY WILLIAM AND CHARLENE STEPHENS 6 TWO STORIES IN REDWORK 10 AQSG SEMINAR 2021 12 MIDWEST FABRIC STUDY GROUP Figure 1: The Jane Gordon quilt, (Fig.1) features an elaborately inked center panel surrounded by an appliquéd wreath. (Photo used with permission of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, #1941-109-1) he 1841 Jane Gordon quilt has been The on-point chintz squares combine with 19 Tat the Philadelphia Museum of Art checkerboard pieced blocks of vibrant VIRgiNia QUILT (PMOA) since it was donated in 1941. Turkey red print to make a very large MUSEUM EXHIBIT A bequest of Philadelphia native Natalie 118 inch by 126 inch quilt. The identical Rowland, the quilt is an illustrative chintz blocks surrounding the intricate example of available fabrics and style inked center contain a very familiar dahlia of mid-nineteenth century design floral noted by quilt historian Barbara in Philadelphia. Brackman in her blog as appearing in at CALENDAR least thirty other mid-century quilts.1 (see ON PAGE 19 Although simple in design, the quilt Fig. 1) nonetheless makes a dramatic statement with its elaborate central block inking. Continued on page 3 Call for Papers The American Quilt Study Group (AQSG) seeks original, previously unpublished research pertaining to the history of quilts, quiltmakers, quiltmaking, associated textiles, and related subjects for inclusion in the annual volume of Uncoverings, a peer-reviewed interdisciplinary journal. Submissions are welcomed on an annual basis, with a firm deadline of June 1 each year. -

162 Hawaiian Quilts: Tradition and Transition. Reiko Mochinaga

Museum Anthropology Review 1(2) Fall 2007 Hawaiian Quilts: Tradition and Transition. Reiko Mochinaga Brandon and Loretta G. H. Woodard. Honolulu: Honolulu Academy of Arts, 2004. 140 pp.∗ Reviewed by Marsha MacDowell In 1989 the Honolulu Academy of Arts partnered with Toshiyuki Higuchi of Kokusai Art to create an exhibition accompanied by a publication edited by Reiko Mochinaga Brandon (The Hawaiian Quilt, Kokusai Art, 1989). The exhibition and publication featured quilts from four Hawaiian museums and profiled the quilts of eleven contemporary quilters. With the addition of Loretta G. H. Woodard, the same team has produced Hawaiian Quilts: Tradition and Transition in tandem with an exhibition of the same name that featured 52 quilts from contemporary artists and 22 historical quilts drawn from three Hawaiian museum collections. Both the latter and the former publications provide a summary of the history of quiltmaking in Hawaii. What is different between the two exhibition catalogues? This time the team is able to draw upon the extensive research that has been undertaken by numerous individuals on different aspects of Hawaiian quiltmaking and, in particular, the work of the Hawaiian Quilt Research Project, a non- profit organization that, since 1990 has registered more than 1500 quilt patterns from thirty- seven public and private collections and more than 1,200 Hawaiian quilts.[1] The introduction to the history of quiltmaking is now enriched and expanded, including important newly-collected information that explores the influence of quilt shows, pattern makers, teachers (especially county extension agents and those affiliated with museums and hotels), collectors (especially Laurence S. Rockefeller), marketing of patterns, tourism, and the inclusion of articles about Hawaiian quiltmaking in nationally-distributed women’s magazines. -

Letter W-Biographical and Necrological Index Cross Co., Ark

Letter W-Biographical and Necrological Index Cross Co., Ark. by Paul V.Isbell, Mar.2,2013 Index:Partial Adams, Caden Lane, 226 Boden, Colin IV, 23 Adams, Emma Grace, 226 Boeckmann, Renee m.Williams, Mrs., 177 Adams, Harland, 102 Boone, Amos, 102 Adams, Herman, 102 Boone, Nevil, 102 Adams, John Q., 216 Boone, Teal, 102 Adams, Kaith Wood, 226 Boyland, Bessie Mae, 168 Adams, Mary Ann m.Wolf, Mrs., 216 Bradley, Bob, 248 Adams, Nellie Jones, Mrs., 102 Bradley, Norris, 248 Adams, Thomas, 102 Brawner, 41 Adams, Wythe (CSA) Vet, 216 Brawner, Ada Elizabeth m.McElroy, Mrs., Allen, Dena m.Webster, mrs., 82 41 Anderson, Lillian Imogene, 248 Brawner, Claude Edgar, Sr., 41 Andrews, H. J., 20 Brawner, Claude, Jr., 41 Andrews, Jackie m.Walker, Mrs., 25, 30 Brawner, Harrell, 41 Armstrong, Naomi m.Waldrep, Mrs., 23 Brawner, Onalee, 41 Bailey, Bobby, 248 Brawner, Rex, 41 Bailey, Jim, 248 Brown, Martha M. m.Wisemore, Mrs. Bailey, Tommie m.Lucas, Mrs., 240 d.1929, 211 Bailey, Vernon Lavelle, 248 Brumback, Diann, Mrs., 144 Ball, Leah, 226 Buck, Sherry Lea m.Williams, Mrs., 169 Ballard, Tolise m.Witcher, Mrs., 214 Burnett, Buford, 169 Banton, Dale, 94 Burnett, David, 169 Banton, Donald, 94 Burroughs, Robert, 20 Banton, Gordon, 94 Burroughs, Sharon, Mrs., 20 Banton, Norman R., 94 Busby, Hubert, 95 Barnes, David, Jr., 126, 127 Busby, Sylvia, Mrs., 95 Baugh, Linda, 214 Campbell, Ida Gay McKinney, Mrs. Baugh, Penny m.Martin, Mrs., 126 d.1906, 68 Bellinger, Jacob d.1902, 212 Campbell, James Thomas d.1926, 68 Bellinger, Rebecca Anna (m.Irwin Irving), Cantwell, Shirley m.Wilday, Mrs., 137 Mrs. -

November Final Draft.PSP

THE QUILTING BEE Quilters’ Guild of Arlington, Inc. PO Box 13232, Arlington, TX 76094 www.qgoa.org Volume XXVII Issue 11 [email protected] November 2011 November Feature December Feature Presentation Presentation Sam Lamoreaux “Confessions of an ADQ Potluck Dinner and (Attention Deficit Quilter)” Brown Bag Auction November 8, 2011 December 13, 2011 She is the owner, teacher and designer Members please bring a salad of The Quilter’s Workshop in or potluck food item to share. Carrollton. Her trunk show will fea- ture some of her quilts starting with The board members will pro- the first one she made in 1987. vide desserts. Renew Your Membership!! Donation Tickets NOW!! Due Back Before the Membership Committe will be doing a new directory and we can all help by December Meeting!! renewing our membership by Jan 10th! Thanks! In case of inclement weather: In general, will do what the Guild Calendar Don't Forget to Bring: University of Texas of Arlington does. Name Tag If they cancel evening classes we will Nov 1 - Board Meeting - 6:30pm Show & Tell Items cancel guild and board meetings. Nov 8 - Guild Meeting - 7 pm Block Party, Linus, Patriotic Sam Lamoreaux Blocks Meeting Location Dec 6 - Board Meeting - 6:30pm Refreshments - T, U, W, X, Y Bob Duncan Community Center Dec 13 - Guild Meeting - 7 pm Pizza Box Challenge Vangergriff Park Safe Haven - Arlington, Texas Children's Toys Doors open at 6:30 ~ Meeting at 7:00 Page 2 THE QUILTING BEE www.qgoa.org November 2011 A Word from our President ~ Hi Quilters, November Birthdays I would like to thank you for electing me as president of the QGOA for another year. -

The Quilt Index: Collaborative Planning for Internationalization Michigan State University Museum

The Quilt Index: Collaborative Planning for Internationalization Michigan State University Museum "The Quilt Index: Collaborative Planning for Internationalization" IMLS National Leadership Grant - Museums Library-Museum Collaboration, Collaborative Planning Level II Summary The Quilt Index is a model online research and reference resource featuring more than 50,000 quilt objects and serving a strong U.S. and expanding international audience. The Quilt Index brings together images of quilts, journals, ephemera, and detailed documentation data from museum, library, private and nonprofit contributors. Michigan State University Museum (MSUM), with the digital library at MATRIX: Center for Humane Arts, Letters and Social Sciences Online, proposes to work with two U.S. partners, the Alliance for American Quilts (AAQ) and the International Quilt Study Center & Museum (IQSC), to lead a collaborative planning process regarding international institutions with quilt collections. Our goal is to identify and examine in detail the most challenging tasks for building a collaborative virtual museum across dozens of countries and cultures and design a blueprint for moving forward. This process will consist of detailed planning instruments and surveys, virtual workshops, and one-on-one consultation activities, all conducted through online and teleconferencing media. These actions will result in: 1) an extensive, online list of international institutions with quilt collections; 2) a published Quilt Index planning and application process specific to international contributors; 3) an overall five-year plan, plus a set of detailed plans and proposals that international institutions holding quilt collections can use to develop projects to contribute their quilt objects to the Index; and 4) a white paper detailing the lessons learned and outlining a planning process that will be useful to any U.S. -

PDF of the AQSG 2019 Seminar Brochure

American Quilt Study Group Fortieth Annual Seminar in partnership with the International Quilt Museum Uncovering Together Lincoln, Nebraska October 9-13, 2019 Tentative Seminar Schedule* *Times are subject to change. You will receive more details when you register. All study centers at hotel unless otherwise noted. Wednesday Friday 2:00 p.m. - 4:00 p.m. 6:00 p.m. October 9 October 11 Study Center Dinner 6:00 p.m. - 8:00 p.m. Breakfast Antique Quilting & Live Auction Needlework Tools Auctions Cash Out Registration 8:00 a.m. - 5:00 p.m. Endowment Table Dawn Cook-Ronningen Sunday Registration Omaha World-Herald Thursday October 13 Endowment Table Contests & Exhibits October 10 Breakfast 8:30 a.m. - 4:30 p.m Donna DiNatale Breakfast Tour Wandering Feet 8:00 a.m. 8:00 a.m. - 5:00 p.m. Stuhr Museum & Broken Needles Registration Registration 8:30 a.m. - 11:30 a.m. Lisa Erlandson Endowment Table Endowment Table Study Centers: IQM 4:30 p.m. - 5:30 p.m. 8:00 a.m. - 9:30 a.m. 9:00 a.m. - 12:00 p.m. Photographing Your Quilts Area Rep Meeting Shipping Service Tour Larry Gawell 4:30 p.m. - 5:30 p.m. 9:00 a.m. New Views Indigo Research Workshop Research Presentation IQM Jay Rich Moving Forward with Invited Speaker 9:00 a.m. - 11:00 a.m. 9:00 a.m. - 12:00 p.m. Your Quilt Research Claire Nicholas Study Centers Tour Publications Committee Annual Meeting Documenting Indigenous Old World Quilts Invitation to Seminar 2020 6:00 p.m. -

Happy New Year!

ABSOLUTELY FREE Vol. 19, No. 1 January 2015 You Can’t Buy It Happy New Year! Calabash #2 is by Ginny Lassiter and is part of the exhibit, An Artist’s Journey, on view January 6 - 31, 2015, at Sunset River Marketplace in Calabash, North Carolina. There will be a reception on Saturday, January 10 from 2 - 5pm. ARTICLE INDEX Advertising Directory This index has active links, just click on the Page number and it will take you to that page. Listed in order in which they appear in the paper. Page 1 - Cover - Ginny Lassiter Page 3 - Morris Whiteside Galleries Morris & Whiteside Auctions, LLC Page 2 - Article Index, Advertising Directory, Contact Info, Links to blogs and Carolina Arts site Page 4 - The Artist Index & Jones-Carter Gallery Page 4 - Editorial Commentary Page 5 - Hampton III Gallery Page 5 - USC-Upstate Page 6 - USC-Upstate & Upstate Heritage Quilt Trail Saturday • February 28, 2015 • 1:00 PM Page 6 - USC-Upstate cont. & Converse College Page 7 - Blue Ridge Arts Center Page 8 - Page 7 - Converse College cont., Furman University and Upstate Heritage Quilt Trail Triangle Artworks & Hillsborough Gallery of Arts Page 9 - Mouse House/Susan Lenz Page 8 - Upstate Heritage Quilt Trail cont., UNC-Chapel Hill & Hillsborough Gallery of Arts Page 10 - South Carolina Governor’s School for the Arts and Humanities, Vista Studios/ Page 9 - Hillsborough Gallery of Arts cont. and University of South Carolina Gallery 80808, Michael Story & The Gallery at Nonnah’s Page 10 - University of South Carolina & City Art Gallery Page 11 - 701 Center for Contemporary Art & City Art Gallery Page 11 - City Art Gallery cont., Fine Arts Center of Kershaw County & Page 12 - One Eared Cow Glass & Gallery 80808 Rental The Johnson Collection and USC Press Page 13 - Fine Art at Baxters Gallery, Wilmington Art Association & Carolina Creations Page 12 - The Johnson Collection and USC Press cont. -

Patricia Cox Crews

1 PATRICIA COX CREWS The University of Nebraska-Lincoln Department of Textiles, Merchandising & Fashion Design Lincoln, Nebraska 68583-0802 Office: (402) 472-6342 Home: (402) 488-8371 EDUCATION Degree Programs 1971 B.S., Virginia Tech, Fashion Design and Merchandising. 1973 M.S., Florida State University, Textile Science. 1984 Ph.D., Kansas State University, Textile Science and Conservation. Other Education 1982 Organic Chemistry for Conservation, Smithsonian Institute Certificate of Training (40 hours). 1985 Historic Dyes Identification Workshop, Smithsonian Conservation Analytical Lab, Washington, D.C. 1990 Colorimetry Seminar, Hunter Associates, Kansas City, MO. 1994 Applied Polarized Light Microscopy, McCrone Research Institute, Chicago, IL. 2007 Museum Leadership Institute, Getty Foundation, Los Angeles, CA. PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE 1984- University of Nebraska-Lincoln, Willa Cather Professor of Textiles, 2003-present; Founding Director Emeritus, International Quilt Study Center & Museum, 1997- 2013; Professor, 1996-present; Acting Chair, Dept. of Textiles, Clothing & Design, 2000; Chair, Interdisciplinary Museum Studies Program, 1995-1997; Associate Professor, 1989-1996; Assistant Professor, 1984-89. Courses taught: Textile History, Care and Conservation of Textile Collections, Artifact Analysis, Textile Dyeing, and Advanced Textiles. 1982 Summer Internship. Smithsonian Institution, National Museum of American History-Division of Textiles. 1977-84 Kansas State University, Manhattan, Kansas, Instructor of Textiles. 1976-77 Bluefield State College, Bluefield, West Virginia, Instructor of Textiles and Weaving. 1975 Virginia Western Community College, Roanoke, Virginia, Instructor of Textiles and Weaving. 1973-74 Oregon State University, Corvallis, Oregon, Instructor of Textiles. HONORS AND AWARDS 2013 Reappointed to Willa Cather Professorship in recognition of distinguished scholarship. 2009 University of Nebraska, College of Education & Human Sciences Faculty Mentoring Award. -

RNQG Programs 2016-17

RNQG Programs 2016-17 September 21, 2016 7:30 – 9 PM Norfolk County Agricultural HS Topic: Welcome Back and 2016-17 RNQG Program Showcase A new quilting year begins… Reunite with quilting friends and enjoy the display of summer challenge quilts! The evening will also feature a slide presentation by 2016-17 RNQG Program Chair Lisa Steinka. Come learn about the lecturers and teachers that will intrigue, teach and inspire us to greater creativity during the 2016-17 quilting season! RNQG Programs 2016-17 October 19, 2016 7:30 – 9PM Norfolk County Agricultural HS Cynthia England Website: englanddesign.com Topic: ”Getting the Most Out of Your Stash” This lecture explores ways to increase the potential of what we already have in our fabric collections. Cynthia will offer new insights on what to look for in fabrics to get the most out of them, a topic that is near and dear to all quilters! Organizing and storage of fabrics will also be addressed. A graduate of the Art Institute of Houston, Cynthia and has been creating quilts for more than forty years. Experimentation with quilting techniques led her to develop the unique style that she calls "Picture Piecing". Cynthia's quilts have been honored with many awards, including two “Best of Show” at the prestigious International Quilt Festival in Houston and “Viewers’ Choice” at the American Quilter’s Society show in Paducah. Her quilt “Piece and Quiet” was distinguished as one of the Hundred Best Quilts of the 20th Century. Cynthia teaches and lectures nationally and internationally. She is the designer/owner of England Design Studios which is a publishing/pattern company specializing in the "Picture Piecing" technique. -

Finding Aid for Cuesta Benberry African and African American Quilt and Quilt History Collection, Michigan State University Museum

1 Cuesta Benberry Quilt Research Collection Finding Aid for Cuesta Benberry African and African American Quilt and Quilt History Collection, Michigan State University Museum Contents Collection Summary ...................................................................................................................................... 3 Collection numbers (DACS 2.1; MARC 099): ............................................................................................. 3 Collection title (DACS 2.3; MARC 245): ..................................................................................................... 3 Dates (DACS 2.4; MARC 245): ................................................................................................................... 3 Size (DACS 2.5; MARC 300): ...................................................................................................................... 3 Creator/Collector (DACS 2.6 & Chapter 9; MARC100, 10, 245, 600): ....................................................... 3 Acquisition info. (DACS 5.2; MARC 584): .................................................................................................. 3 Accruals (DACS 5.4; MARC 584): ............................................................................................................... 4 Custodial history (DACS 5.1; MARC 561): ................................................................................................. 4 Language (DACS 4.5; MARC 546): ............................................................................................................ -

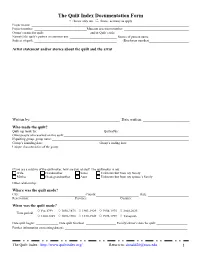

The Quilt Index Documentation Form

The Quilt Index Documentation Form ○ choose only one choose as many as apply Project name: Project number: Museum accession number: Owner’s name for quilt: and/or Quilt’s title: Name(s) for quilt’s pattern in common use: Source of pattern name: Subject of quilt: (Brackman number) Artist statement and/or stories about the quilt and the artist Written by: Date written: Who made the quilt? Quilt top made by: Quilted by: Other people who worked on this quilt: If quilting group, group name: Group’s founding date: Group’s ending date: Unique characteristics of the group: If you are a relative of the quiltmaker, how are you related? The quiltmaker is my: Wife Grandmother Sister Unknown but from my family Mother Great-grandmother Aunt Unknown but from my spouse’s family Other relationship: Where was the quilt made? City: County: State: Reservation: Province: Country: When was the quilt made? ○ Pre-1799 ○ 1850-1875 ○ 1901-1929 ○ 1950-1975 ○ 2000-2025 Time period: ○ 1800-1849 ○ 1876-1900 ○ 1930-1949 ○ 1976-1999 ○ Timepsan Date quilt begun: Date quilt finished: Family/owner’s date for quilt: Further information concerning date(s): The Quilt Index: http://www.quiltindex.org/ Return to: [email protected] 1 The Quilt Index Documentation Form ○ choose only one choose as many as apply Why was the quilt made? Art or personal expression Commemorative Mourning Therapy Anniversary Fundraising Personal enjoyment Wedding Autograph or friendship Gift or presentation Personal income Unknown Baby or crib Home decoration Reunion Not described