The O&W Model Shop

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Aviation Consumer April 2010

April 2010 Volume XL Number 4 The consumer resource for pilots and aircraft owners Legend Amphib Respectable performance, good build quality and just crazy fun … page 22 Plastic trumps paper … page 4 JPI’s new monitors… page 8 Actually, it’s even worse than it looks… page 18 4 TABLET EFBs 11 KNEEBOARD ROUNDUP 18 AUTOPILOT NIGHTMARE It’s a tough call to pick a true For a place to write and keep a In case you haven’t noticed, winner, but ChartCase is it pen, we like Sporty’s Classic. the AP market is just a mess 8 JPI’S NEW 730/830 14 BARGAIN RETRACTS 24 USED AIRCRAFT GUIDE: Sophisticated new monitors That’s all of them these days. Practicality and durability are are ideal for tight panels The Arrow is a top pick why the Piper Archer endures FIRST WORD EDITOR Paul Bertorelli Blue Screen of Death in the Cockpit Maybe I emit some kind of weird electromagnetic field, but it seems if there’s MANAGING EDITOR a way to get a computer to crash, I’ll find it. Back in my dot.com, tech-writer Jeff Van West days people loved to have me beta test software because I’d break it within five minutes. I’ve even found bugs in MFDs weeks before certification. CONTRIBUTING EDITORS This knack held right into our EFB trials that you’ll see on page four. We Jeb Burnside had started up the engine and I was having trouble getting the device to Jonathan Doolittle respond correctly. Simple solution: reboot. -

Types and Characteristics of Locomotives Dr. Ahmed A. Khalil Steam Locomotives - Operating Principle

Types and Characteristics of Locomotives Dr. Ahmed A. Khalil Steam Locomotives - Operating Principle: The wheel is connected to the rod by a crank. The rod is connected to the piston rod of the steam cylinder., thereby converting the reciprocating motion of the piston rod generated by steam power into wheel rotation. - Main Parts of a steam locomotive: 1. Tender — Container holding both water for the boiler and combustible fuel such as wood, coal or oil for the fire box. 2. Cab — Compartment from which the engineer and fireman can control the engine and tend the firebox. 3. Whistle — Steam powered whistle, located on top of the boiler and used as a signalling and warning device. 4. Reach rod — Rod linking the reversing actuator in the cab (often a 'johnson bar') to the valve gear. 5. Safety valve — Pressure relief valve to stop the boiler exceeding the operating limit. 6. Generator — Steam powered electric generator to power pumps, head lights etc, on later locomotives. 7. Sand box/Sand dome — Holds sand that can be deposited on the rails to improve traction, especially in wet or icy conditions. 8. Throttle Lever — Controls the opening of the regulator/throttle valve thereby controlling the supply of steam to the cylinders. 9. Steam dome — Collects the steam at the top of the boiler so that it can be fed to the engine via the regulator/throttle valve. 10. Air pump — Provides air pressure for operating the brakes (train air brake system). 11. Smoke box — Collects the hot gas that have passed from the firebox and through the boiler tubes. -

O-Steam-Price-List-Mar2017.Pdf

Part # Description Package Price ======== ================================================== ========= ========== O SCALE STEAM CATALOG PARTS LIST 2 Springs, driver leaf........................ Pkg. 2 $6.25 3 Floor, cab and wood grained deck............. Ea. $14.50 4 Beam, end, front pilot w/coupler pocket...... Ea. $8.00 5 Beam, end, rear pilot w/carry iron.......... Ea. $8.00 6 Bearings, valve rocker....................... Pkg.2 $6.50 8 Coupler pockets, 3-level, for link & pin..... Pkg. 2 $5.75 9 Backhead w/fire door base.................... Ea. $9.00 10 Fire door, working........................... Ea. $7.75 11 Journal, 3/32" bore.......................... Pkg. 4. $5.75 12 Coupler pockets, small, S.F. Street Railway.. Pkg.2 $5.25 13 Brakes, engine............................... Pkg.2 $7.00 14 Smokebox, 22"OD, w/working door.............. Ea. $13.00 15 Drawbar, rear link & pin..................... Ea. $5.00 16 Handles, firedoor............................ Pkg.2. $5.00 17 Shelf, oil can, backhead..................... Ea. $5.75 18 Gauge, backhead, steam pressure.............. Ea. $5.50 19 Lubricator, triple-feed, w/bracket, Seibert.. Ea. $7.50 20 Tri-cock drain w/3 valves, backhead.......... Ea. $5.75 21 Tri-cock valves, backhead, (pl. 48461)....... Pkg. 3 $5.50 23 Throttle, nonworking......................... Ea. $6.75 23.1 Throttle, non working, plastic............... Ea. $5.50 24 Pop-off, pressure, spring & arm.............. Ea. $6.00 25 Levers, reverse/brake, working............... Kit. $7.50 26 Tri-cock drain, less valves.................. Ea. $5.75 27 Seat boxes w/backs........................... Pkg.2 $7.50 28 Injector w/piping, Penberthy,................ Pkg.2 $6.75 29 Oiler, small hand, N/S....................... Pkg.2 $6.00 32 Retainers, journal........................... Pkg. -

Spare Parts Catalog in PDF Format

- The Baker Talt,e $ear I K Locomotive Talye $ears foIanufactured by THE PILLIOD COMPANY 3o Church St., New York Railway Exchange, Chicago ORKS: SWANTON, OHIO - - THE BAKER LOCOMOTIVE VALVE GEAR HE LocoMorrvE Valvr GneR, governing as it does the distribution of steam to the cylinders, performs one of the most important functions of the loco- motive machinery. It should be well designed, manufactured with mechanical precision, and, last but not least it nrust be maintain.ed in every day service. Mainte- nance, as we understand it, means first, proper and ample lubrication, inspection and adjustment and lastly, replace- ment of worn parts. Considering that a force of some five thousand pounds is put in operation to move a locomotive valve and that this force momentum changes its direction twice with each reyo- lution of the drivers, it must be evident even to those not experienced in locomotive operation that a wearing process is taking place in the yalve gear parts. When this wear develops into lost motion between parts, the efficiency of the valve gear is impaired and the locomotive loses its tractive power, consumes more coal and water, and eventually fails because of broken parts, resulting in train delays and other expensiye operating difficulties. THr Bercn Ver.vr Gran has been designed through many years of experience, first, to give efficient seryice and second, to provide easy and inexpensive maintenance; it is manufac- tured as nearly perfect as any machinery can be. Our manu- facturing plant located on the New York Central Lines at Swanton, Ohio, just west of Toledo, is engaged exclusively in building locomotive valve gears and parts and is the only plant in this country, perhaps in the world, devoted to this one line. -

Steam Simulator Operating Manual

Highball Sim **** STEAM LOCOMOTIVE SIMULATOR Based on the Santa Fe & Disneyland Railroad 5/8th Narrow Gauge Railroad OPERATING MANUAL **** by Preston Nirattisai Los Angeles, CA based on simulator version 1.0.0.2017-12 **** ckhollidayplans.com Contents Contents iv Foreword vii Acknowledgements xi Introduction xiii 1 Installing, Updates, and Support 1 1.1 Installing and Running . 1 1.2 Updates . 1 1.3 Uninstalling . 2 1.4 Support . 2 1.5 License . 2 2 The Simulator 3 2.1 Quick Start . 4 2.2 Navigating the Simulator . 9 2.3 Controls . 11 2.4 Home Menu . 15 2.5 Main Menu . 17 2.6 Tracks and Scenery Configuration . 35 2.7 Quick Engine Setup . 36 2.8 Pause Menu . 38 2.9 Failure Dialogue . 38 3 The Locomotives 41 3.1 History . 41 3.2 Engine Components . 42 3.3 Cab Controls . 56 4 Firing Up a Cold Engine 63 5 Water Management (Fireman) 69 5.1 Water quantity . 69 5.2 Water Contents . 76 iv 6 Steam and Pressure Management 79 6.1 Steam Loss . 80 6.2 Boiler Pressure Safety . 85 7 Firing and Fire Management 87 7.1 Creating, Building, and Maintaining a Fire . 89 7.2 Fire Indications . 95 7.3 Refilling the Water and Fuel . 96 7.4 Firing on Compressed Air . 97 8 Running a Steam Locomotive (Engineer) 99 8.1 Locomotive Construction . 99 8.2 Physics of a Steam Locomotive . 102 8.3 Stephenson Valve Gear . 104 8.4 Throttle and Johnson Bar . 105 8.5 Engine and Train Lubrication . 112 8.6 Air Compressor . -

New Haven Steam

New Haven Steam I‐4‐e #1385 W‐10‐c tender A detail study for modelers By Chris Adams, Charlie Dunn, Randy Hammill and the NHRHTA Photo Library Overview Scope is classes with HO Scale models available Focus is on prototype and applies to all scales Highlight variations within a class Highlight modifications over time Switchers Freight Passenger o T‐2‐b o K‐1‐b/d o G‐4 J‐1 I‐2 o Y‐3 o o o L‐1 o I‐4 o Y‐4 o R‐1 o I‐5 o R‐3‐a Common Modifications Headlights o <1917 ‐ Oil headlights o 1917‐1920 ‐ Pyle National (?) cylindrical headlights. Not all were replaced. o 1920‐1924 ‐ Pyle National (?) on new locomotives except R‐1‐a class #3310‐#3339. o ESSCo Golden Glow headlights starting in 1926. Brass number boards red for passenger locomotives, and black for freight and switchers. Pilots <1937 – Boiler tube. >1937 –Steel Strap –phased in over time. >1931 – Pilot plows applied to many (most?) locomotives, often removed in spring/summer Footboard pilots on many locomotives in local freight service (often on tender as well). Other c1927+ – Spoked pilot wheels replaced with disc wheels c1940’s – Compressed air clappers applied to many bells Headlights Oil Pyle National (?) ESSCo Golden Glow Pyle National vs. Golden Glow Pyle National Headlight from UP Big Boy ESSCo Golden Glow Headlight Note side mounted hinge Note top mounted hinge Pilots Boiler Tube Boiler Tube with pilot plow Foot board Steel Strap with pilot plow Steel Strap The New Haven Railroad and Tenders o The New Haven frequently swapped tenders o Turntable length limited size of early tenders o Large tenders were purchased for Shoreline service o Tender class changed when a stoker was installed. -

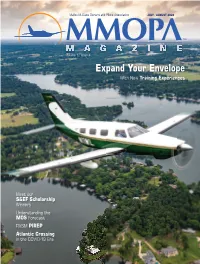

Expand Your Envelope with New Training Experiences

Malibu M-Class Owners and Pilots Association JULY / AUGUST 2020 MAGAZINE Volume 10 Issue 4 Expand Your Envelope With New Training Experiences Meet our S&EF Scholarship Winners Understanding the MOS Forecast RVSM PIREP Atlantic Crossing in the COVID-19 Era Legacy Flight Training Full Page 4/CAd 4/C IFC IFC IFC www.legacyflighttraining.com 2 MMOPA MAGAZINE JULY / AUGUST 2020 EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR’S NOTE MAGAZINE by Dianne White Executive Director and Editor Dianne White 18149 Goddard St. Overland Park, KS 66013 E-mail: [email protected] (316) 213-9626 Publishing Office 2779 Aero Park Drive 2020: Making Traverse City, MI 49686 Phone: (660) 679-5650 Advertising Director Go/No-Go Decisions John Shoemaker MMOPA 2779 Aero Park Drive Traverse City, MI 49686 Phone: 1-800-773-7798 ow’s your summer going? If you’re like most, your plans for travel, Fax: (231) 946-9588 vacation and business trips required some rerouting or outright E-mail: [email protected] cancelation. Making a go/no-go decision on a trip also involved Advertising Administrative looking at virus hotspots and what quarantine mandates exist at Coordinator & Reprint Sales Betsy Beaudoin your home base and at your destination. Presently, my home state of 2779 Aero Park Drive HKansas has a list of states that if you visit you must undergo a 14-day quarantine Traverse City, MI 49686 Legacy Flight Training Phone: 1-800-773-7798 upon returning home. But, I’ve been fortunate to do quite a bit of flying the past Fax: (231) 946-9588 45 days, which helped keep my skills sharp and logbook current. -

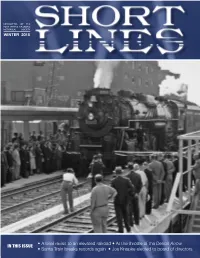

• a Brief Revisit to an Elevated Railroad • at the Throttle of the Detroit Arrow

NEWSLETTER OF THE FORT WAYNE RAILROAD HISTORICAL SOCIETY WINTER 2015 • A brief revisit to an elevated railroad • At the throttle of the Detroit Arrow IN THIS ISSUE • Santa Train breaks records again • Joe Knapke elected to board of directors NEWSLETTER OF THE FORT WAYNE RAILROAD HISTORICAL SOCIETY WINTER 2015 Homeward bound on the 765’s last trip of 2014. Brandon Townsley When the extraordinary becomes commonplace, it is no less remarkable Volunteer Ken Wentland engages passengers within the warm confines of Nickel Plate Caboose no. 141. By Kelly Lynch, Editor The long steel rail and our 400-ton time accomplishment in the steps of the 765 and her Record breaking Santa Train carries on community tradition machine took us on another adventure in crew - the kind that engine crews in their crisp By Kelly Lynch, Editor 2014. The famed Water Level Route made for denim and chore coats must have once felt at Last December, our long-running Santa Train event expected to be able to immediately board the train, most fast, easy running on employee appreciation the end of a day’s shift 60 years ago. received a significant upgrade by way of offering advance were content with a wait no longer than 45 minutes, a tour specials for Norfolk Southern between Elkhart, In August, we had our first planning ticket sales for the first time in history. of the 765, and kids had the option of watching the Polar Indiana and Bryan, Ohio. The 765 muscled meeting for 2015 with Norfolk Southern. Over 3,000 passengers visited us in 2013, at times Express while they waited. -

T H E G E N E R a T

Newsletter of THE PALMERSTON NORTH MODEL ENGINEERING CLUB INC Managers of the “MARRINER RESERVE RAILWAY” Please address all correspondence to :- 22b Haydon St, Palmerston North. PRESIDENT SECRETARY TREASURER EDITOR Richard Lockett Stuart Anderson Murray Bold Doug Chambers (06) 323-0948 (06) 357-7794 (06) 355-7000 (06) 354-9379 September [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] 2009 No 349 PNMEC Home Page www.pnmec.org.nz Email:- [email protected] TRACK RUNNING T This is held on the FIRST and THIRD Sunday of each month, from 1 pm to 4 pm Summer and 1 pm to 3 pm during the Winter. All club members are welcome to attend and help out with loco coaling, watering and passenger marshalling - none of the tasks being at all H Visiting club members are always welcome at the track, at the monthly meeting, or if just visiting and wishing to make contact with members, please phone one of the above office bearers. E Sender:- PNMEC Place 22b Haydon St, stamp Palmerston North here G E N E This Months Featured Model R A T O R - 2 - making them. Long term plan is to use the Sirius to REPORT on the power a generator. John Tweedie has been making the ‗Grasshopper‘ August Meeting. engine described in the Australian Model Engineering Richard Lockett spoke on the manufacture of magazine. The 10‖ diameter disc, 1‖ thick that he piston rod glands from leaded gunmetal. acquired for the flywheel was too big to swing in his He explained that a mandrel held in a collet is lathe so he machined it under the milling machine. -

2001 MODEL RAILROADING ▼ 5 NEW BODY STYI,E! HEAVYWEIGHT DEPRESSED-CENTER FLAT CAR Wjbuckeye TRUCKS

▼ AMHERST CONTEST WINNERS ▼ REVIEWS ▼ INTERMODAL CONTAINERS ▼ DIESEL DETAIL: MILW GP40 ▼ Jan/Feb 2001 $4.50 Higher in Canada JIM POWERS’ On3 ColoradoColorado && SouthernSouthernPAGE 50 ModelingTransamericaTransamerica Modern Intermodal DistributionDistribution ServicesServices Page 35 St. Paul Coal Co. 01 > EMDEMD GP40sGP40s Page 20 Page 24 0 7447 0 91672 7 More than just your average locomotive, the Baldwin 2-6-0 was railroad royalty. Making its debut alongside the 4-4-0 at the Centennial Exhibition celebrating the United States' 100th anniversary, the 2-6-0 carried 4 million of the visitors around the Exhibition site. Its impressive size and strength led the engine to be christened the "Mogul," and the 2-6-0 reigned over the narrow gauge rails of its day. Bachmann's Spectrum@ 2-6-0 Mogul is a 1 :20.3 large scale reproduction of the revered Baldwin locomotive. It features prototypical detailing and parts, including a working Stephenson valve gear with operating piston valves, Johnson bar, and linkage. Also included is a polarity switch that allows you to � choose the direction the 2-6-0 travels (either according to NMRA standards or large scale model railroad practice). A perfect companion to the SpectrumlB! 4-4-0 Centennial, our new 2-6-0 exhibits all the power and style needed to make it your railroad Mogul. January 2001 VOLUME 31 NUMBER 1 FEATURES 20 ▼ GP40: The First 645 Geep Part 6: Denver & Rio Grande Western 60 by George Melvin Photo by Jim Mansfield 24 ▼ St. Paul Coal Mine in Cherry, Illinois — Site of the Cherry Mine Disaster, 50 ▼ Jim Powers’ On3 November 13, 1909 Colorado & Southern Narrow Gauge Part 2: The St. -

November 2018

News of The Riverside Live Steamers November 2018 Jerry Blake at the throttle of Richard Ronne’s 0-6-0 “Even if you're on the right track, you'll get run over if you just sit there. ” - Will Rodgers - 2 President’s Words Of Wisdom - Hi there boys and Girls! This is the last article that your going to be forced to read from me before a new President is elected by the up- coming Board. It then falls on them to write the December Chron Presidents message. It's been a good year for the club and I'm pleased to have been involved at the outside of it all. Bob Roberts and his merry band of gophers has been hard at the underground plumbing with great success. it isn't done yet, and if Bob asks for some week- day help and you can become one of the merry band, please do. The third level in the car barn is moving along, albeit slowly because of the heat. Remarkably, we haven't had to force the storage chair- man to move too much stuff around because of the height re- strictions now placed on engines. The Fall meet, while quiet engine wise still had the same good bunch of folks hanging out and sharing the warm SoCal Fall weather. A big tip o' the hat to the O'Guinn family yet again. The breakfasts were at the sublime level that we have come to expect. If and when you see Pat, tell him thanks, and ask him to pass it on to his brother who had done all the planning and then the cooking. -

Accucraft Fairymead 0-4-2

Accucraft Fairymead 0-4-2 AL87-810 7/8ths Fairymead Green AL87-812 7/8ths Fairymead Black Instruction Manual 0-4-2 Fairymead Note: Please read the entire manual prior to operation Unpacking and Assembly Remove inner box from the shipping carton, lift open and remove locomotive in its cocoon from the box. Set aside the small parts box for later use. Place the board on a hard surface and using a razor knife cut along the board edge. Carefully pull off the tape and plastic from the locomotive. Discard all tape and plastic. You will notice that the headlamp and stack were not shipped installed to avoid damage in transit. In the next steps we will install these on the locomotive. Open the small parts box and remove the tools, lamp and stack as you will now need a M2 and M3 nut driver to install the headlamp. You will also need a small pair of needle nose pliers (not included) to tighten the smokestack. Using the M2 nutdriver remove the 2 bolts on each side retaining the smoke box front, Be careful not to damage the finish. Set the screws aside and gently pull the front off with your fingers through the opened door. Next remove the brass deflector and insulation wrapping the inside smokebox. Instruction Manual 0-4-2 Fairymead The smokestack will be installed next, remove the nut and curved washed from the stack and insert the stack and base through the opening in the smokebox. Support the stack at all times and insert the curved washer then the nut.