Tyrant! Tipu Sultan and the Reconception of British Imperial Identity, 1780-1800

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Karnataka Tourism Vision Group 2014 Report

Karnataka Tourism Vision group 2014 report KARNATAKA TOURISM VISION GROUP (KTVG) Recommendations to the GoK: Jan 2014 Task force KTVG Karnataka Tourism Vision Group 2014 Report 1 FOREWORD Tourism matters. As highlighted in the UN WTO 2013 report, Tourism can account for 9% of GDP (direct, indirect and induced), 1 in 11 jobs and 6% of world exports. We are all aware of amazing tourist experiences globally and the impact of the sector on the economy of countries. Karnataka needs to think big, think like a Nation-State if it is to forge ahead to realise its immense tourism potential. The State is blessed with natural and historical advantage, which coupled with a strong arts and culture ethos, can be leveraged to great advantage. If Karnataka can get its Tourism strategy (and brand promise) right and focus on promotion and excellence in providing a wholesome tourist experience, we believe that it can be among the best destinations in the world. The impact on job creation (we estimate 4.3 million over the next decade) and economic gain (Rs. 85,000 crores) is reason enough for us to pay serious attention to focus on the Tourism sector. The Government of Karnataka had set up a Tourism Vision group in Oct 2013 consisting of eminent citizens and domain specialists to advise the government on the way ahead for the Tourism sector. In this exercise, we had active cooperation from the Hon. Minister of Tourism, Mr. R.V. Deshpande; Tourism Secretary, Mr. Arvind Jadhav; Tourism Director, Ms. Satyavathi and their team. The Vision group of over 50 individuals met jointly in over 7 sessions during Oct-Dec 2013. -

A St. Helena Who's Who, Or a Directory of the Island During the Captivity of Napoleon

A ST. HELENA WHO'S WHO A ST. HELENA WHO'S WHO ARCHIBALD ARNOTT, M.D. See page si. A ST. HELENA WHO'S WHO OR A DIRECTORY OF THE ISLAND DURING THE CAPTIVITY OF NAPOLEON BY ARNOLD gHAPLIN, M.D. (cantab.) Author of The Illness and Death of Napoleon, Thomas Shortt, etc. NEW YORK E. P. DUTTON AND COMPANY LONDON : ARTHUR L. HUMPHREYS 1919 SECOND EDITION REVISED AND ENLARGED PREFACE The first edition of A St. Helena Whos Wlio was limited to one hundred and fifty copies, for it was felt that the book could appeal only to those who were students of the period of Napoleon's captivity in St. Helena. The author soon found, however, that the edition was insuffi- cient to meet the demand, and he was obliged, with regret, to inform many who desired to possess the book that the issue was exhausted. In the present edition the original form in which the work appeared has been retained, but fresh material has been included, and many corrections have been made which, it is hoped, will render the book more useful. vu CONTENTS PAQI Introduction ....... 1 The Island or St. Helena and its Administration . 7 Military ....... 8 Naval ....... 9 Civil ....... 10 The Population of St. Helena in 1820 . .15 The Expenses of Administration in St. Helena in 1817 15 The Residents at Longwood . .16 Topography— Principal Residences . .19 The Regiments in St. Helena . .22 The 53rd Foot Regiment (2nd Battalion) . 22 The 66th Foot Regiment (2nd Battalion) . 26 The 66th Foot Regiment (1st Battalion) . 29 The 20th Foot Regiment . -

PART 1 of Volume 13:6 June 2013

LANGUAGE IN INDIA Strength for Today and Bright Hope for Tomorrow Volume 13:6 June 2013 ISSN 1930-2940 Managing Editor: M. S. Thirumalai, Ph.D. Editors: B. Mallikarjun, Ph.D. Sam Mohanlal, Ph.D. B. A. Sharada, Ph.D. A. R. Fatihi, Ph.D. Lakhan Gusain, Ph.D. Jennifer Marie Bayer, Ph.D. S. M. Ravichandran, Ph.D. G. Baskaran, Ph.D. L. Ramamoorthy, Ph.D. Assistant Managing Editor: Swarna Thirumalai, M.A. Contents Drama in Indian Writing in English - Tradition and Modernity ... 1-101 Dr. (Mrs.) N. Velmani Reflection of the Struggle for a Just Society in Selected Poems of Niyi Osundare and Mildred Kiconco Barya ... Febisola Olowolayemo Bright, M.A. 102-119 Identity Crisis in Jhumpa Lahiri’s The Namesake ... Anita Sharma, M.Phil., NET, Ph.D. Research Scholar 120-125 A Textual Study of Context of Personal Pronouns and Adverbs in Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner” ... Fadi Butrus K Habash, M.A. 126-146 Crude Oil Price Behavior and Its Impact on Macroeconomic Variable: A Case of Inflation ... M. Anandan, S. Ramaswamy and S. Sridhar 147-161 Using Exact Formant Structure of Persian Vowels as a Cue for Forensic Speaker Recognition ... Mojtaba Namvar Fargi, Shahla Sharifi, Mohammad Reza Pahlavan-Nezhad, Azam Estaji, and Mehi Meshkat Aldini Ferdowsi University of Mashhad 162-181 Language in India www.languageinindia.com ISSN 1930-2940 13:6 June 2013 Contents List i Simplification of CC Sequence of Loan Words in Sylheti Bangla ... Arpita Goswami, Ph.D. Research Scholar 182-191 Impact of Class on Life A Marxist Study of Thomas Hardy’s Novel Tess of the D’Urbervilles .. -

Planning Region: Characteristics, Economic Regionalization and Identification of Indian Planning Regions (V

UG, 4th Semester (H) CC-09-TH- Regional Planning and Development 3. Planning region: Characteristics, economic regionalization and identification of Indian Planning Regions (V. Nath, P. Sengupta & TCPO) Planning region: A planning region is a segment of territory (space) over which economic decisions apply. The term 'planning' in the present context means taking decisions to implement them in order to attain economic development. Planning regions may be administrative or political regions such as state, district or the block because such regions are better in management and collecting statistical data. For proper implementation and realization of plan objectives, a planning region should have fairly homogeneous economic, to zoographical and socio-cultural structure. It should be large enough to contain a range of resources provide it economic viability. It should also internally cohesive. Its resource endowment should be that a satisfactory level of product combination consumption and exchange is feasible. It should have some nodal points to regulate the flows. According to Keeble-“Planning Region is an area that is large enough to enable substantial changes in the distribution of population and employment to take place within this boundaries, yet which is small enough for its planning problem to be viewed as a whole”. According to Klaassen- “A planning region must be large enough to take investment decisions of an economic size, must be able to supply its own industry with the necessary labour, should have a homogeneous economic structure, contain at least one growth point and have a common approach to and awareness of its problems”. As a whole- A planning region is self created living organism having a life line. -

Western Ghats & Sri Lanka Biodiversity Hotspot

Ecosystem Profile WESTERN GHATS & SRI LANKA BIODIVERSITY HOTSPOT WESTERN GHATS REGION FINAL VERSION MAY 2007 Prepared by: Kamal S. Bawa, Arundhati Das and Jagdish Krishnaswamy (Ashoka Trust for Research in Ecology & the Environment - ATREE) K. Ullas Karanth, N. Samba Kumar and Madhu Rao (Wildlife Conservation Society) in collaboration with: Praveen Bhargav, Wildlife First K.N. Ganeshaiah, University of Agricultural Sciences Srinivas V., Foundation for Ecological Research, Advocacy and Learning incorporating contributions from: Narayani Barve, ATREE Sham Davande, ATREE Balanchandra Hegde, Sahyadri Wildlife and Forest Conservation Trust N.M. Ishwar, Wildlife Institute of India Zafar-ul Islam, Indian Bird Conservation Network Niren Jain, Kudremukh Wildlife Foundation Jayant Kulkarni, Envirosearch S. Lele, Centre for Interdisciplinary Studies in Environment & Development M.D. Madhusudan, Nature Conservation Foundation Nandita Mahadev, University of Agricultural Sciences Kiran M.C., ATREE Prachi Mehta, Envirosearch Divya Mudappa, Nature Conservation Foundation Seema Purshothaman, ATREE Roopali Raghavan, ATREE T. R. Shankar Raman, Nature Conservation Foundation Sharmishta Sarkar, ATREE Mohammed Irfan Ullah, ATREE and with the technical support of: Conservation International-Center for Applied Biodiversity Science Assisted by the following experts and contributors: Rauf Ali Gladwin Joseph Uma Shaanker Rene Borges R. Kannan B. Siddharthan Jake Brunner Ajith Kumar C.S. Silori ii Milind Bunyan M.S.R. Murthy Mewa Singh Ravi Chellam Venkat Narayana H. Sudarshan B.A. Daniel T.S. Nayar R. Sukumar Ranjit Daniels Rohan Pethiyagoda R. Vasudeva Soubadra Devy Narendra Prasad K. Vasudevan P. Dharma Rajan M.K. Prasad Muthu Velautham P.S. Easa Asad Rahmani Arun Venkatraman Madhav Gadgil S.N. Rai Siddharth Yadav T. Ganesh Pratim Roy Santosh George P.S. -

Mysore Tourist Attractions Mysore Is the Second Largest City in the State of Karnataka, India

Mysore Tourist attractions Mysore is the second largest city in the state of Karnataka, India. The name Mysore is an anglicised version of Mahishnjru, which means the abode of Mahisha. Mahisha stands for Mahishasura, a demon from the Hindu mythology. The city is spread across an area of 128.42 km² (50 sq mi) and is situated at the base of the Chamundi Hills. Mysore Palace : is a palace situated in the city. It was the official residence of the former royal family of Mysore, and also housed the durbar (royal offices).The term "Palace of Mysore" specifically refers to one of these palaces, Amba Vilas. Brindavan Gardens is a show garden that has a beautiful botanical park, full of exciting fountains, as well as boat rides beneath the dam. Diwans of Mysore planned and built the gardens in connection with the construction of the dam. Display items include a musical fountain. Various biological research departments are housed here. There is a guest house for tourists.It is situated at Krishna Raja Sagara (KRS) dam. Jaganmohan Palace : was built in the year 1861 by Krishnaraja Wodeyar III in a predominantly Hindu style to serve as an alternate palace for the royal family. This palace housed the royal family when the older Mysore Palace was burnt down by a fire. The palace has three floors and has stained glass shutters and ventilators. It has housed the Sri Jayachamarajendra Art Gallery since the year 1915. The collections exhibited here include paintings from the famed Travancore ruler, Raja Ravi Varma, the Russian painter Svetoslav Roerich and many paintings of the Mysore painting style. -

International Journal of South Asian Studies

ISSN 0974 - 2514 International Journal of GUIDELINES FOR SUBMISSION OF MANUSCRIPTS South Asian Studies Original papers that fall within the scope of the Journal shall be submitted by e-mail. An Abstract of the article in about 150 words A Biannual Journal of South Asian Studies must accompany the papers. The length of research papers shall be between 5000 and 7000 words. However, short notes, perspectives and lengthy papers will be published if the contents could justify. Notes should be placed at the end of the text and their Vol. 2 January – June 2009 No. 1 location in the text marked by superscript Arabic Numerals. References should be cited within the text in parenthesis. Example : (Sambandhan 2007:190) Bibliography should be placed at the end of the text and must be complete in all respects. Examples: 1. Hoffmann, Steven (1990): India and the China Crisis, Oxford University Press, Delhi. 2. Bhalla and Hazell (2003): “Rural Employment and Poverty: Strategies to Eliminate Rural Poverty within a Generation”, Economic and Political Weekly, Vol.33, No.33, August 16, pp.3473-84. All articles are, as a rule, referred to experts in the subjects concerned. Those recommended by the referees alone will be published in the Journal after appropriate editing. No article shall be sent for publication in the Journal if it is currently being reviewed by any other Journal or press or if it has already been published or will be published elsewhere. e-mail: [email protected] or [email protected] SOCIETY FOR SOUTH ASIAN STUDIES Department of Politics & International Studies Pondicherry University Puducherry, India International Journal of South Asian Studies IJSAS January - June 2008 International Journal of South Asian Studies IJSAS January - June 2008 Contents New Discourse in Gender and Local Governance: A Comparative Study on Sri Lanka and India D Parimala .. -

Mehendale Book-10418

Tipu as He Really Was Gajanan Bhaskar Mehendale Tipu as He Really Was Copyright © Gajanan Bhaskar Mehendale First Edition : April, 2018 Type Setting and Layout : Mrs. Rohini R. Ambudkar III Preface Tipu is an object of reverence in Pakistan; naturally so, as he lived and died for Islam. A Street in Islamabad (Rawalpindi) is named after him. A missile developed by Pakistan bears his name. Even in India there is no lack of his admirers. Recently the Government of Karnataka decided to celebrate his birth anniversary, a decision which generated considerable opposition. While the official line was that Tipu was a freedom fighter, a liberal, tolerant and enlightened ruler, its opponents accused that he was a bigot, a mass murderer, a rapist. This book is written to show him as he really was. To state it briefly: If Tipu would have been allowed to have his way, most probably, there would have been, besides an East and a West Pakistan, a South Pakistan as well. At the least there would have been a refractory state like the Nizam's. His suppression in 1792, and ultimate destruction in 1799, had therefore a profound impact on the history of India. There is a class of historians who, for a long time, are portraying Tipu as a benevolent ruler. To counter them I can do no better than to follow Dr. R. C. Majumdar: “This … tendency”, he writes, “to make history the vehicle of certain definite political, social and economic ideas, which reign supreme in each country for the time being, is like a cloud, at present no bigger than a man's hand, but which may soon grow in volume, and overcast the sky, covering the light of the world by an impenetrable gloom. -

The Madras Presidency, with Mysore, Coorg and the Associated States

: TheMADRAS PRESIDENG 'ff^^^^I^t p WithMysore, CooRGAND the Associated States byB. THURSTON -...—.— .^ — finr i Tin- PROVINCIAL GEOGRAPHIES Of IN QJofttell HttinerHitg Blibracg CHARLES WILLIAM WASON COLLECTION CHINA AND THE CHINESE THE GIFT OF CHARLES WILLIAM WASON CLASS OF 1876 1918 Digitized by Microsoft® Cornell University Library DS 485.M27T54 The Madras presidencypresidenc; with MysorMysore, Coor iliiiiliiiiiiilii 3 1924 021 471 002 Digitized by Microsoft® This book was digitized by Microsoft Corporation in cooperation witli Cornell University Libraries, 2007. You may use and print this copy in limited quantity for your personal purposes, but may not distribute or provide access to it (or modified or partial versions of it) for revenue-generating or other commercial purposes. Digitized by Microsoft® Provincial Geographies of India General Editor Sir T. H. HOLLAND, K.C.LE., D.Sc, F.R.S. THE MADRAS PRESIDENCY WITH MYSORE, COORG AND THE ASSOCIATED STATES Digitized by Microsoft® CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS HonBnn: FETTER LANE, E.G. C. F. CLAY, Man^gek (EBiniurBi) : loo, PRINCES STREET Berlin: A. ASHER AND CO. Ji-tipjifl: F. A. BROCKHAUS i^cto Sotfe: G. P. PUTNAM'S SONS iBomlaj sriB Calcutta: MACMILLAN AND CO., Ltd. All rights reserved Digitized by Microsoft® THE MADRAS PRESIDENCY WITH MYSORE, COORG AND THE ASSOCIATED STATES BY EDGAR THURSTON, CLE. SOMETIME SUPERINTENDENT OF THE MADRAS GOVERNMENT MUSEUM Cambridge : at the University Press 1913 Digitized by Microsoft® ffiambttige: PRINTED BY JOHN CLAY, M.A. AT THE UNIVERSITY PRESS. Digitized by Microsoft® EDITOR'S PREFACE "HE casual visitor to India, who limits his observations I of the country to the all-too-short cool season, is so impressed by the contrast between Indian life and that with which he has been previously acquainted that he seldom realises the great local diversity of language and ethnology. -

Socio-Economic and Political Status of Panchayats Elected Representatives (A Study of Mysore District-Karnataka)

IOSR Journal Of Humanities And Social Science (IOSR-JHSS) Volume 19, Issue 5, Ver. I (May. 2014), PP 51-55 e-ISSN: 2279-0837, p-ISSN: 2279-0845. www.iosrjournals.org Socio-economic and political status of panchayats Elected representatives (A Study of Mysore District-Karnataka) H. M. Mohan Kumari1 and Dr. Ashok Kumar, H2 Abstract: The paper presents the structure and functions of Panchayati raj Institutions. It also highlights the social composition of elected members and their participation in the decision making process in PRIs. Liberal Democracy is one of the basic features of the Indian Constitution. Mahatma Gandhi advocated Panchayat Raj even before Independence. The further of the Nation felt that as issues at the village levels must be addressed by the people only under self-governance and the State or the Central Governments only facilitate such self-rule through grants and by conferring autonomy on them. Panchayat system had earlier an informal setup to redress the local issues and problems of communities which were mainly social and economic in nature. They were popular institutions at micro levels and the main objective was to keep the local community in harmony and to encourage participation in the process of development. The Mysore Government in 1902 passed the Mysore Local Boards Act with a view to revitaling the rural local Government. In 1918, the Mysore Government enacted the Mysore Local Boards and Village Panchayat Act making provisions for elected representatives at the district and taluk levels. After Independence, District and Taluk Boards were set up by the Mysore Government. The first independent legislation on Panchayat Raj Institutions was enacted by the Ramakrishna Hegde Government in 1983 and was brought into effect from April 1987 with the first elections to these local bodies in rural areas. -

I I J. J. J. J. J. J

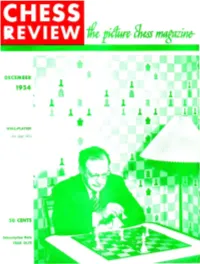

t i i DECEMB ER * 1954 1 J. ~ J. 1 ~ 1 I J. I 1 1 1 1 J. J. J. t i WA LL~PlAY E D ! (.'H'I- IJU!!" .1 5.1/ 50 CENTS Svbsf:ripti on Rate YEA R SUS Dresden, 1892 RUY LOPEZ TaHasch ~ Iarco While Bla ck I P- K4 P- K4 4 P- Q4 B- Q2 2 N- KS3 N- QB3 5 N-B3 B- K 2 3 B_N5 P- Q3 S 0 - 0 N_' 7 R_K l 0 - T he I)oint! T his, the mOSI pl!l nsi ble InOl'e on t he boan !, loses: The l'l ght move is i PxP, giving liP t he cente r. 8 BxN BxB 10 QxQ QRxQ ANNOTATORS may he divided into lwo classes : 9 PxP Px P 11 NxP Bx? In the first class are Alekhine, TalTa,;ch and .\IJarco, Everyhody Or" 11 NxP 12 !\xB. :-"x N 13 S"x Dt. ebc llclongs in the second class, K - IU H PxN :: While wins t ll" O Iliel'e~, 12 NxB NxN 14 P- KB3 B- B4t 13 N-Q3! P_ KB4 15 NxB NxN II LEK H INF~ had a rat'e abllUy us an 12 B_B2 P- QR3 RnalY1lt with whlrh IU0 1l t of 1111 are fa, 13 Q-83 P_N4 16 B_N5 R- Q4 mlllar. We have playetl lIu'ough hIs notes 14 Q-R3 If 16 " , QH- Kl, 17 B- 1\7 wi ns. itl the .19 ~ 2 Hastinll:s TOIIl"namenl book or Whit e t hre!lt"ll~ I ~ NxN. -

Bangalore for the Visitor

Bangalore For the Visitor PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Mon, 12 Dec 2011 08:58:04 UTC Contents Articles The City 11 BBaannggaalloorree 11 HHiissttoorryoofBB aann ggaalloorree 1188 KKaarrnnaattaakkaa 2233 KKaarrnnaattaakkaGGoovv eerrnnmmeenntt 4466 Geography 5151 LLaakkeesiinBB aanngg aalloorree 5511 HHeebbbbaalllaakkee 6611 SSaannkkeeyttaannkk 6644 MMaaddiiwwaallaLLaakkee 6677 Key Landmarks 6868 BBaannggaalloorreCCaann ttoonnmmeenntt 6688 BBaannggaalloorreFFoorrtt 7700 CCuubbbboonPPaarrkk 7711 LLaalBBaagghh 7777 Transportation 8282 BBaannggaalloorreMM eettrrooppoolliittaanTT rraannssppoorrtCC oorrppoorraattiioonn 8822 BBeennggaalluurruIInn tteerrnnaattiioonnaalAA iirrppoorrtt 8866 Culture 9595 Economy 9696 Notable people 9797 LLiisstoof ppee oopplleffrroo mBBaa nnggaalloorree 9977 Bangalore Brands 101 KKiinnggffiisshheerAAiirrll iinneess 110011 References AArrttiicclleSSoo uurrcceesaann dCC oonnttrriibbuuttoorrss 111155 IImmaaggeSS oouurrcceess,LL iicceennsseesaa nndCC oonnttrriibbuuttoorrss 111188 Article Licenses LLiicceennssee 112211 11 The City Bangalore Bengaluru (ಬೆಂಗಳೂರು)) Bangalore — — metropolitan city — — Clockwise from top: UB City, Infosys, Glass house at Lal Bagh, Vidhana Soudha, Shiva statue, Bagmane Tech Park Bengaluru (ಬೆಂಗಳೂರು)) Location of Bengaluru (ಬೆಂಗಳೂರು)) in Karnataka and India Coordinates 12°58′′00″″N 77°34′′00″″EE Country India Region Bayaluseeme Bangalore 22 State Karnataka District(s) Bangalore Urban [1][1] Mayor Sharadamma [2][2] Commissioner Shankarlinge Gowda [3][3] Population 8425970 (3rd) (2011) •• Density •• 11371 /km22 (29451 /sq mi) [4][4] •• Metro •• 8499399 (5th) (2011) Time zone IST (UTC+05:30) [5][5] Area 741.0 square kilometres (286.1 sq mi) •• Elevation •• 920 metres (3020 ft) [6][6] Website Bengaluru ? Bangalore English pronunciation: / / ˈˈbæŋɡəɡəllɔəɔər, bæŋɡəˈllɔəɔər/, also called Bengaluru (Kannada: ಬೆಂಗಳೂರು,, Bengaḷūru [[ˈˈbeŋɡəɭ uuːːru]ru] (( listen)) is the capital of the Indian state of Karnataka.