The French Court and the Principle of Legality I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Case for Structured Proportionality Under the Second Limb of the Lange Test

THE BALANCING ACT: A CASE FOR STRUCTURED PROPORTIONALITY UNDER THE SECOND LIMB OF THE LANGE TEST * BONINA CHALLENOR This article examines the inconsistent application of a proportionality principle under the implied freedom of political communication. It argues that the High Court should adopt Aharon Barak’s statement of structured proportionality, which is made up of four distinct components: (1) proper purpose; (2) rational connection; (3) necessity; and (4) strict proportionality. The author argues that the adoption of these four components would help clarify the law and promote transparency and flexibility in the application of a proportionality principle. INTRODUCTION Proportionality is a term now synonymous with human rights. 1 The proportionality principle is well regarded as the most prominent feature of the constitutional conversation internationally.2 However, in Australia, the use of proportionality in the context of the implied freedom of political communication has been plagued by confusion and controversy. Consequently, the implied freedom of political communication has been identified as ‘a noble and idealistic enterprise which has failed, is failing, and will go on failing.’3 The implied freedom of political communication limits legislative power and the common law in Australia. In Lange v Australian Broadcasting Corporation, 4 the High Court unanimously confirmed that the implied freedom5 is sourced in the various sections of the Constitution which provide * Final year B.Com/LL.B (Hons) student at the University of Western Australia. With thanks to Murray Wesson and my family. 1 Grant Huscroft, Bradley W Miller and Grégoire Webber, Proportionality and the Rule of Law (Cambridge University Press, 2014) 1. -

Autumn 2015 Newsletter

WELCOME Welcome to the CHAPTER III Autumn 2015 Newsletter. This interactive PDF allows you to access information SECTION NEWS easily, search for a specific item or go directly to another page, section or website. If you choose to print this pdf be sure to select ‘Fit to A4’. III PROFILE LINKS IN THIS PDF GUIDE TO BUTTONS HIGH Words and numbers that are underlined are COURT & FEDERAL Go to main contents page dynamic links – clicking on them will take you COURTS NEWS to further information within the document or to a web page (opens in a new window). Go to previous page SIDE TABS AAT NEWS Clicking on one of the tabs at the side of the Go to next page page takes you to the start of that section. NNTT NEWS CONTENTS Welcome from the Chair 2 Feature Article One: No Reliance FEATURE Necessary for Shareholder Class ARTICLE ONE Section News 3 Actions? 12 Section activities and initiatives Feature Article Two: Former employees’ Profile 5 entitlement to incapacity payments under the Safety, Rehabilitation and FEATURE Law Council of Australia / Federal Compensation Act 1988 (Cth) 14 ARTICLE TWO Court of Australia Case Management Handbook Feature Article Three: Contract-based claims under the Fair Work Act post High Court of Australia News 8 Barker 22 Practice Direction No 1 of 2015 FEATURE Case Notes: 28 ARTICLE THREE Judicial appointments and retirements Independent Commission against High Court Public Lecture 2015 Corruption v Margaret Cunneen & Ors [2015] HCA 14 CHAPTER Appointments Australian Communications and Media Selection of Judicial speeches -

Situating Women Judges on the High Court of Australia: Not Just Men in Skirts?

Situating Women Judges on the High Court of Australia: Not Just Men in Skirts? Kcasey McLoughlin BA (Hons) LLB (Hons) A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, the University of Newcastle January 2016 Statement of Originality This thesis contains no material which has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma in any university or other tertiary institution and, to the best of my knowledge and belief, contains no material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference has been made in the text. I give consent to the final version of my thesis being made available worldwide when deposited in the University's Digital Repository, subject to the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. Kcasey McLoughlin ii Acknowledgments I am most grateful to my principal supervisor, Jim Jose, for his unswerving patience, willingness to share his expertise and for the care and respect he has shown for my ideas. His belief in challenging disciplinary boundaries, and seemingly limitless generosity in mentoring others to do so has sustained me and this thesis. I am honoured to have been in receipt of his friendship, and owe him an enormous debt of gratitude for his unstinting support, assistance and encouragement. I am also grateful to my co-supervisor, Katherine Lindsay, for generously sharing her expertise in Constitutional Law and for fostering my interest in the High Court of Australia and the judges who sit on it. Her enthusiasm, very helpful advice and intellectual guidance were instrumental motivators in completing the thesis. The Faculty of Business and Law at the University of Newcastle has provided a supportive, collaborative and intellectual space to share and debate my research. -

THE ADELAIDE LAW REVIEW Law.Adelaide.Edu.Au Adelaide Law Review ADVISORY BOARD

Volume 40, Number 3 THE ADELAIDE LAW REVIEW law.adelaide.edu.au Adelaide Law Review ADVISORY BOARD The Honourable Professor Catherine Branson AC QC Deputy Chancellor, The University of Adelaide; Former President, Australian Human Rights Commission; Former Justice, Federal Court of Australia Emeritus Professor William R Cornish CMG QC Emeritus Herchel Smith Professor of Intellectual Property Law, University of Cambridge His Excellency Judge James R Crawford AC SC International Court of Justice The Honourable Professor John J Doyle AC QC Former Chief Justice, Supreme Court of South Australia Professor John V Orth William Rand Kenan Jr Professor of Law, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Professor Emerita Rosemary J Owens AO Former Dean, Adelaide Law School The Honourable Justice Melissa Perry Federal Court of Australia The Honourable Margaret White AO Former Justice, Supreme Court of Queensland Professor John M Williams Dame Roma Mitchell Chair of Law and Former Dean, Adelaide Law School ADELAIDE LAW REVIEW Editors Associate Professor Matthew Stubbs and Dr Michelle Lim Book Review and Comment Editor Dr Stacey Henderson Associate Editors Kyriaco Nikias and Azaara Perakath Student Editors Joshua Aikens Christian Andreotti Mitchell Brunker Peter Dalrymple Henry Materne-Smith Holly Nicholls Clare Nolan Eleanor Nolan Vincent Rocca India Short Christine Vu Kate Walsh Noel Williams Publications Officer Panita Hirunboot Volume 40 Issue 3 2019 The Adelaide Law Review is a double-blind peer reviewed journal that is published twice a year by the Adelaide Law School, The University of Adelaide. A guide for the submission of manuscripts is set out at the back of this issue. -

The Changing Position and Duties of Company Directors

CRITIQUE AND COMMENT THE CHANGING POSITION AND DUTIES OF COMPANY DIRECTORS T HE HON JUSTICE GEOFFREY NETTLE* In 1974, in the first edition of his Principles of Company Law, Professor Ford was able to say that directors’ duties were ‘not very demanding’. This lecture traces how the duties and standards of care demanded of company directors have increased since then. In doing so, it makes reference to the attenuated business judgment rule, comparing the positions in the United Kingdom and, briefly, South Africa. It then considers similarities and differences between the duties imposed on company directors, union officers and public officials. It suggests that, while the regulatory regimes that apply to company directors and union officers are strikingly different, there is little reason in principle why that should be so. For practical reasons, the same cannot be said of the differences between public officials and company directors or union officers. But it remains somewhat paradoxical that, although the actions of public officials may have far more broad- ranging effects on the nation’s wellbeing than the actions of any company director or union officer, public officials’ duties are much less onerous. CONTENTS I Introduction ............................................................................................................ 1403 II Directors’ Duties .................................................................................................... 1404 A The Development of Directors’ Duties in Equity ................................ -

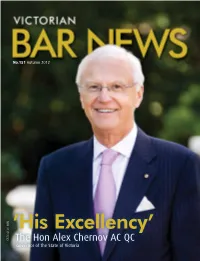

'His Excellency'

AROUND TOWN No.151 Autumn 2012 ISSN 0159 3285 ISSN ’His Excellency’ The Hon Alex Chernov AC QC Governor of the State of Victoria 1 VICTORIAN BAR NEWS No. 151 Autumn 2012 Editorial 2 The Editors - Victorian Bar News Continues 3 Chairman’s Cupboard - At the Coalface: A Busy and Productive 2012 News and Views 4 From Vilnius to Melbourne: The Extraordinary Journey of The Hon Alex Chernov AC QC 8 How We Lead 11 Clerking System Review 12 Bendigo Law Association Address 4 8 16 Opening of the 2012 Legal Year 19 The New Bar Readers’ Course - One Year On 20 The Bar Exam 20 Globe Trotters 21 The Courtroom Dog 22 An Uncomfortable Discovery: Legal Process Outsourcing 25 Supreme Court Library 26 Ethics Committee Bulletins Around Town 28 The 2011 Bar Dinner 35 The Lineage and Strength of Our Traditions 38 Doyle SC Finally Has Her Say! 42 Farewell to Malkanthi Bowatta (DeSilva) 12 43 The Honourable Justice David Byrne Farewell Dinner 47 A Philanthropic Bar 48 AALS-ABCC Lord Judge Breakfast Editors 49 Vicbar Defeats the Solicitors! Paul Hayes, Richard Attiwill and Sharon Moore 51 Bar Hockey VBN Editorial Committee 52 Real Tennis and the Victorian Bar Paul Hayes, Richard Attiwill and Sharon Moore (Editors), Georgina Costello, Anthony 53 Wigs and Gowns Regatta 2011 Strahan (Deputy Editors), Ben Ihle, Justin Tomlinson, Louise Martin, Maree Norton and Benjamin Jellis Back of the Lift 55 Quarterly Counsel Contributors The Hon Chief Justice Warren AC, The Hon Justice David Ashley, The Hon Justice Geoffrey 56 Silence All Stand Nettle, Federal Magistrate Phillip Burchardt, The Hon John Coldrey QC, The Hon Peter 61 Her Honour Judge Barbara Cotterell Heerey QC, The Hon Neil Brown QC, Jack Fajgenbaum QC, John Digby QC, Julian Burnside 63 Going Up QC, Melanie Sloss SC, Fiona McLeod SC, James Mighell SC, Rachel Doyle SC, Paul Hayes, 63 Gonged! Richard Attiwill, Sharon Moore, Georgia King-Siem, Matt Fisher, Lindy Barrett, Georgina 64 Adjourned Sine Die Costello, Maree Norton, Louise Martin and James Butler. -

Alumni News2005v11.Indd

POSTCARDS AND LETTERS HONOURS DEATHS (August 2003 – July 2005) OBITUARIES Alumni News Supplement to Trinity Update August 2005 Trinity College 2004 AUSTRALIA DAY HONOURS Dr Yvonne AITKEN, AM (1930) REGINALD LESLIE STOCK, OBE, COLIN PERCIVAL JUTTNER JOHN GORDON RUSHBROOKE THE UNIVERSITY OF MELBOURNE Dr Nancy AUN (1976) 1909-2004 1910-2003 1936-2003 Hugh Wilson BALLANTYNE (1951) AC Reg Stock entered Trinity in 1929, studying for a Following in his father’s footsteps, Colin Juttner entered John Rushbrooke entered Trinity from Geelong Grammar in What a kaleidoscope of activities is reflected in this collection of news items, gathered since August 2003 from Peter BALMFORD (1946) Leonard Gordon DARLING (TC 1940), AO, CMG, combined Arts/Law degree. He was elected Secretary Trinity from St Peter’s College, Adelaide, in 1929 and 1954 with a General Exhibition. He completed his BSc in Alumni and Friends of Trinity College, the University of Melbourne. We hope this new trial format will help to Dr (William) Ronald BEETHAM, AM (1949) Melbourne, Victoria. For service to the arts through of the Fleur de Lys Club in 1932 and Senior Student enrolled in the Faculty of Medicine. He took a prominent 1956, graduating with prizes in Mathematics and Physics. rekindle memories and prompt some renewed contacts, and apologise if any details have become dated. vision, advice and philanthropy for long-term benefit Dr Garry Edward Wilbur BENNETT (1938) in 1933. As such he chaired the meeting of the Club part in student life, representing the College in cricket His Master’s degree saw him begin his work as a high to the nation. -

2015-16 High Court of Australia Annual Report

HIGH COURT OF AUSTRALIA ANNUAL REPORT 2015–2016 © High Court of Australia 2016 ISSN 0728–4152 (print) ISSN 1838–2274 (on-line) This work is copyright, but the on-line version may be downloaded and reprinted free of charge. Apart from any other use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth), no part may be reproduced by any other process without prior written permission from the High Court of Australia. Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to the Manager, Public Information, High Court of Australia, GPO Box 6309, Kingston ACT 2604 [email protected]. Images © Adam McGrath Designed by Spectrum Graphics sg.com.au High Court of Australia Canberra ACT 2600 25 October 2016 Dear Attorney In accordance with section 47 of the High Court of Australia Act 1979 (Cth), I submit on behalf of the High Court and with its approval a report relating to the administration of the affairs of the Court under section 17 of the Act for the year ended 30 June 2016, together with financial statements in respect of the year in the form approved by the Minister for Finance. Section 47(3) of the Act requires you to cause a copy of this report to be laid before each House of Parliament within 15 sitting days of that House after its receipt by you. Yours sincerely Andrew Phelan Chief Executive and Principal Registrar of the High Court of Australia Senator the Honourable George Brandis QC Attorney-General Parliament House Canberra ACT 2600 TABLE OF CONTENTS PART 1 – PREAMBLE 5 PART 6 – ADMINISTRATION 31 Overview 31 -

The Case for Abolishing the Offence of Scandalising the Judiciary

Daniel O’Neil* THE CASE FOR ABOLISHING THE OFFENCE OF SCANDALISING THE JUDICIARY ABSTRACT This article assesses the philosophical foundations and the practical remit of the common law offence of scandalising the judiciary (also known as ‘scandalising contempt’), and finds that the continued existence of this offence as presently constituted cannot be justified. The elements and scope of this offence, it is suggested, are ill-defined, which is a matter of great concern given its potentially fierce penal consequences. Moreover, given the extent to which it may interfere with free expression of opinion on an arm of government, the offence’s compatibility with the implied freedom of political communication guaranteed by the Australian Constitution is also discussed — though it is noted that in most instances, prosecutions for the offence will not infringe this protection. The article concludes by suggesting that the common law offence must either by abolished by legislative fiat or replaced by a more narrowly confined statutory offence. It is suggested that an expression of genuinely held belief on a matter of such profound public interest as the administration of justice should not be the subject of proceedings for contempt of court. I INTRODUCTION ow far can one go in criticising a Judge?’1 This is the question at the heart of the common law offence known as scandalising the judiciary — an ‘H offence that may sound ‘wonderfully archaic’,2 yet is regrettably anything but. This article attempts to chart the metes and bounds of this offence and to assess its empirical application in Australia and elsewhere. It is concluded that the offence is both vague in definition and savage in its potential punitive consequences. -

Proceedings of the Samuel Griffith Society, Volume 28

Upholding the Australian Constitution Volume Twenty-eight Proceedings of the Twenty-eighth Conference of The Samuel Griffith Society Stamford Plaza, Adelaide SA — 12–14 August 2016 © Copyright 2018 by The Samuel Griffith Society. All rights reserved. Contents Introduction Eddy Gisonda The Eighth Sir Harry Gibbs Memorial Oration The Honourable Robert French Giving and Taking Offence Chapter One Brendan O’Neill Hatred: A Defence Chapter Two John Roskam and Morgan Begg Prior v QUT & Ors [2016] Chapter Three The Honourable Tony Abbott Cultural Self-Confidence: That is What is Missing Chapter Four The Honourable Chris Kourakis In re Revenue Taxation & the Federation: The States v The Commonwealth Chapter Five Jeffrey Goldsworthy Is Legislative Supremacy Under Threat?: Statutory Interpretation, Legislative Intention, and Common Law Principles Chapter Six Lael K. Weis Originalism in Australia Chapter Seven Simon Steward Taxation of Multinationals: OECD Guidelines and the Rule of Law i Chapter Eight James Allan Australian Universities, Law Schools and Teaching Human Rights Chapter Nine Margaret Cunneen Great Harm to Innocent People: An ICAC story Chapter Ten David Smith The Dismissal: Reflections 40 Years On Chapter Eleven Don Morris Reserve Powers of the Crown: Perils of Definition Chapter Twelve Ken Coghill The Speaker Chapter Thirteen Peter Patmore Clerks of Houses of Parliament Contributors ii Introduction Eddy Gisonda The Samuel Griffith Society held its 28th Conference on the weekend of 12 to 14 August 2016, in the city of Adelaide, South -

Extending the Critical Rereading Project

EXTENDING THE CRITICAL REREADING PROJECT Gabrielle Appleby & Rosalind Dixon* We want to start by congratulating Kathryn Stanchi, Linda Berger, and Bridget Crawford for a wonderful collection of feminist judgments that provide a rich and provocative rereading of U.S. Supreme Court gender-justice cases.1 It is an extremely important contribution to the growing international feminist judgments project—in which leading feminist academics, lawyers, and activists imagine alternative feminist judgments to existing legal cases—which commenced with the seminal UK Feminist Judgments Project.2 The original 2010 UK Project was based on the initially online Canadian community known as the Canadian Women’s Court.3 These works bring feminist critiques of legal doctrine from an external, commentary-based perspective to a position where such critiques might breathe reality into the possibility of feminist judgment writing. A feminist rewriting can change the way the story is told, the voices that are heard in the story, and the context in which it unfolds. Today, the feminist judgments project, having expanded across © 2018 Gabrielle Appleby and Rosalind Dixon. Individuals and nonprofit institutions may reproduce and distribute copies of this Symposium in any format, at or below cost, for educational purposes, so long as each copy identifies the authors, provides a citation to the Notre Dame Law Review Online, and includes this provision and copyright notice. * Gabrielle Appleby is an Associate Professor, Co-Director of the Judiciary Project, Gilbert + Tobin Centre of Public Law, University of New South Wales. Rosalind Dixon is a Professor, Director of the Comparative Constitutional Law Project, Gilbert + Tobin Centre of Public Law, and Deputy Director of the Herbert Smith Freehills Initiative on Law and Economics, University of New South Wales. -

1 Implied Freedom of Political Communication

1 Implied freedom of Political Communication – development of the test and tools Chris Bleby 1. The implied freedom of political communication was first announced in Nationwide News v Wills1 and Australian Capital Television Pty Ltd v The Commonwealth.2 As Brennan J described the freedom at this nascent stage:3 “the legislative powers of the Parliament are so limited by implication as to preclude the making of a law trenching upon that freedom of discussion of political and economic matters which is essential to sustain the system of representative government prescribed by the Constitution.” 2. ACTV concerned Part IIID of the Broadcasting Act 1942 (Cth), which was introduced by the Political Broadcasts and Political Disclosures Act 1991 (Cth). It contained various prohibitions, with exemptions, on broadcasting on behalf of the Commonwealth government in an election period, and prohibited a broadcaster from broadcasting a “political advertisement” on behalf of a person other than a government or government authority or on their own behalf. 3. Chief Justice Mason’s judgment remains the starting point of the implied freedom for its analysis based in ss 7 and 24 of the Constitution. His Honour also ventured a test to be applied for when the implied freedom could be said to be infringed. This was a lengthy, descriptive test. Critically, he observed that the freedom was only one element of a society controlled by law:4 Hence, the concept of freedom of communication is not an absolute. The guarantee does not postulate that the freedom must always and necessarily prevail over competing interests of the public.