After the Party (Quark)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

November 2, 2019 Julien's Auctions: Property From

JULIEN’S AUCTIONS: PROPERTY FROM THE COLLECTION OF OLIVIA NEWTON-JOHN PRESS RELEASE For Immediate Release: JULIEN’S AUCTIONS: PROPERTY FROM THE COLLECTION OF OLIVIA NEWTON-JOHN Four-Time Grammy Award-Winning Pop Diva and Hollywood Superstar’s Iconic “Grease” Leather Jacket and Pants, “Physical” and “Xanadu” Wardrobe Pieces, Gowns, Awards and More to Rock the Auction Stage Portion of the Auction Proceeds to Benefit the Olivia Newton-John Cancer Wellness & Research Centre https://www.onjcancercentre.org NOVEMBER 2, 2019 Los Angeles, California – (June 18, 2019) – Julien’s Auctions, the world-record breaking auction house, honors one of the most celebrated and beloved pop culture icons of all time with their PROPERTY FROM THE COLLECTION OF OLIVIA NEWTON-JOHN (OBE, AC, HONORARY DOCTORATE OF LETTERS (LA TROBE UNIVERSITY)) auction event live at The Standard Oil Building in Beverly Hills and online at juliensauctions.com. Over 500 of the most iconic film and television worn costumes, ensembles, gowns, personal items and accessories owned and used by the four-time Grammy award-winning singer/Hollywood film star and one of the best-selling musical artists of all time who has sold 100 million records worldwide, will take the auction stage headlining Julien’s Auctions’ ICONS & IDOLS two-day music extravaganza taking place Friday, November 1st and Saturday, November 2nd, 2019. PAGE 1 Julien’s Auctions | 8630 Hayden Place, Culver City, California 90232 | Phone: 310-836-1818 | Fax: 310-836-1818 © 2003-2019 Julien’s Auctions JULIEN’S AUCTIONS: PROPERTY FROM THE COLLECTION OF OLIVIA NEWTON-JOHN PRESS RELEASE The Cambridge, England born and Melbourne, Australia raised singer and actress began her music career at the age of 14, when she formed an all-girl group, Sol Four, with her friends. -

Let Me Be There a – 1973 Olivia Newton-John

Let Me Be There A – 1973 Olivia Newton-John 4/4 A D A A / D A Where ever you go, where ever you may wander in your life. A / E / Surely you know I always want to be there. A / D A Holding your hand and standing by to catch you when you fall. A E A NC Seeing you thru in ev'rything you do. Chorus: A / D / Let me be there in your morning, let me be there in your night. A / B(7) E Let me change whatever's wrong and make it right. A / D / Let me take you through that wonderland that only two can share. A E A / All I ask you is let me be there. A / D A Watching you grow and going thru the changes in your life. A / E / That's how I know I'll always want to be there. A / D A Whenever you feel you need a friend to lean on, here I am A E A NC Whenever you call, you know I'll be there. Go to next page Let Me Be There (cont.) Chorus: A / D / Let me be there in your morning, let me be there in your night. A / B(7) E Let me change whatever's wrong and make it right. A / D / Let me take you through that wonderland that only two can share. A E A / All I ask you is let me be there. (Repeat chorus) Ending A E A / All I ask you is let me be there. -

Songs by Artist

Sound Master Entertianment Songs by Artist smedenver.com Title Title Title .38 Special 2Pac 4 Him Caught Up In You California Love (Original Version) For Future Generations Hold On Loosely Changes 4 Non Blondes If I'd Been The One Dear Mama What's Up Rockin' Onto The Night Thugz Mansion 4 P.M. Second Chance Until The End Of Time Lay Down Your Love Wild Eyed Southern Boys 2Pac & Eminem Sukiyaki 10 Years One Day At A Time 4 Runner Beautiful 2Pac & Notorious B.I.G. Cain's Blood Through The Iris Runnin' Ripples 100 Proof Aged In Soul 3 Doors Down That Was Him (This Is Now) Somebody's Been Sleeping Away From The Sun 4 Seasons 10000 Maniacs Be Like That Rag Doll Because The Night Citizen Soldier 42nd Street Candy Everybody Wants Duck & Run 42nd Street More Than This Here Without You Lullaby Of Broadway These Are Days It's Not My Time We're In The Money Trouble Me Kryptonite 5 Stairsteps 10CC Landing In London Ooh Child Let Me Be Myself I'm Not In Love 50 Cent We Do For Love Let Me Go 21 Questions 112 Loser Disco Inferno Come See Me Road I'm On When I'm Gone In Da Club Dance With Me P.I.M.P. It's Over Now When You're Young 3 Of Hearts Wanksta Only You What Up Gangsta Arizona Rain Peaches & Cream Window Shopper Love Is Enough Right Here For You 50 Cent & Eminem 112 & Ludacris 30 Seconds To Mars Patiently Waiting Kill Hot & Wet 50 Cent & Nate Dogg 112 & Super Cat 311 21 Questions All Mixed Up Na Na Na 50 Cent & Olivia 12 Gauge Amber Beyond The Grey Sky Best Friend Dunkie Butt 5th Dimension 12 Stones Creatures (For A While) Down Aquarius (Let The Sun Shine In) Far Away First Straw AquariusLet The Sun Shine In 1910 Fruitgum Co. -

Songs by Artist

Songs by Artist Title Title (Hed) Planet Earth 2 Live Crew Bartender We Want Some Pussy Blackout 2 Pistols Other Side She Got It +44 You Know Me When Your Heart Stops Beating 20 Fingers 10 Years Short Dick Man Beautiful 21 Demands Through The Iris Give Me A Minute Wasteland 3 Doors Down 10,000 Maniacs Away From The Sun Because The Night Be Like That Candy Everybody Wants Behind Those Eyes More Than This Better Life, The These Are The Days Citizen Soldier Trouble Me Duck & Run 100 Proof Aged In Soul Every Time You Go Somebody's Been Sleeping Here By Me 10CC Here Without You I'm Not In Love It's Not My Time Things We Do For Love, The Kryptonite 112 Landing In London Come See Me Let Me Be Myself Cupid Let Me Go Dance With Me Live For Today Hot & Wet Loser It's Over Now Road I'm On, The Na Na Na So I Need You Peaches & Cream Train Right Here For You When I'm Gone U Already Know When You're Young 12 Gauge 3 Of Hearts Dunkie Butt Arizona Rain 12 Stones Love Is Enough Far Away 30 Seconds To Mars Way I Fell, The Closer To The Edge We Are One Kill, The 1910 Fruitgum Co. Kings And Queens 1, 2, 3 Red Light This Is War Simon Says Up In The Air (Explicit) 2 Chainz Yesterday Birthday Song (Explicit) 311 I'm Different (Explicit) All Mixed Up Spend It Amber 2 Live Crew Beyond The Grey Sky Doo Wah Diddy Creatures (For A While) Me So Horny Don't Tread On Me Song List Generator® Printed 5/12/2021 Page 1 of 334 Licensed to Chris Avis Songs by Artist Title Title 311 4Him First Straw Sacred Hideaway Hey You Where There Is Faith I'll Be Here Awhile Who You Are Love Song 5 Stairsteps, The You Wouldn't Believe O-O-H Child 38 Special 50 Cent Back Where You Belong 21 Questions Caught Up In You Baby By Me Hold On Loosely Best Friend If I'd Been The One Candy Shop Rockin' Into The Night Disco Inferno Second Chance Hustler's Ambition Teacher, Teacher If I Can't Wild-Eyed Southern Boys In Da Club 3LW Just A Lil' Bit I Do (Wanna Get Close To You) Outlaw No More (Baby I'ma Do Right) Outta Control Playas Gon' Play Outta Control (Remix Version) 3OH!3 P.I.M.P. -

The Winonan - 1970S

Winona State University OpenRiver The inonW an - 1970s The inonW an – Student Newspaper 5-7-1974 The inonW an Winona State University Follow this and additional works at: https://openriver.winona.edu/thewinonan1970s Recommended Citation Winona State University, "The inonW an" (1974). The Winonan - 1970s. 124. https://openriver.winona.edu/thewinonan1970s/124 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the The inonW an – Student Newspaper at OpenRiver. It has been accepted for inclusion in The inonW an - 1970s by an authorized administrator of OpenRiver. For more information, please contact [email protected]. May 7,.1974 Volume 50 Number 24 8 pages WINONA STATE COLLEGE 50th year of publication Concert Next Monday Night Olivia Newton-John Comes To Winona State Olivia Newton-John, internationally be a greater success in Europe and England popular recording artist, will be coming to than in this country. Olivia was a frequent Winona State College next Monday night. guest on all the major television shows in The concert will begin at 7:30 p.m. and will Britain over the past two years, and now be held in Somsen Auditorium. has taken off on a tour of the United States, accompanied by a seven piece back-up Olivia has been in show business for many band. years, performing with British vocalist Cliff Richard on many of his recordings, Her current hit is "Let Me Be There," a and on his television show. However, it was song which has received air play in every not until 1971 that she achieved attention in major market area of the country, and America. -

Aretha Franklin Looking out on the Morning Rain I Used to Feel So

A1: Natural Woman – Aretha Franklin Looking out on the morning rain I used to feel so uninspired And when I knew I had to face another day Lord, it made me feel so tired Before the day I met you, life was so unkind But your the key to my peace of mind 'Cause you make me feel You make me feel You make me feel like A natural woman (woman) When my soul was in the lost and found You came along to claim it I didn't know just what was wrong with me Till your kiss helped me name it Now I'm no longer doubtful, of what I'm living for And if I make you happy I don't need to do more 'Cause you make me feel You make me feel You make me feel like A natural woman (woman) Oh, baby, what you've done to me (what you've done to me) You make me feel so good inside (good inside) And I just want to be, close to you (want to be) You make me feel so alive You make me feel You make me feel You make me feel like A natural woman (woman) (repeat to close) A2: Across the Universe - Beatles Words are flowing out like endless rain into a paper cup, They slither while they pass, they slip away across the universe Pools of sorrow, waves of joy are drifting through my open mind, Possessing and caressing me. Jai guru deva om Nothing's gonna change my world, Nothing's gonna change my world. -

OLIVIA NEWTON-JOHN Biography

OLIVIA NEWTON-JOHN Biography “I am committed and excited about educating and encouraging women to take a positive role in their breast health.” – Olivia Newton-John Born in Cambridge, England in 1948, the youngest child of Professor Brin Newton-John and Irene, daughter of Nobel Prize winning physicist, Max Born, Olivia moved to Melbourne, Australia with her family when she was five. By the age of fifteen, she had formed an all-girl group called Sol Four. Later that year she won a talent contest on the popular TV show, “Sing, Sing, Sing,” which earned her a trip to London. By 1963, Olivia was appearing on local daytime TV shows and weekly pop music programs in Australia. Olivia cut her first single for Decca Records in 1966, a version of Jackie DeShannon’s "Till You Say You’ll Be Mine." In 1971, she recorded a cover of Bob Dylan’s "If Not For You," co-produced by John Farrar, who she continues to collaborate with today. Her 1973 U.S. album debut, "Let Me Be There," produced her first top ten single of the same name, with Olivia being honored by the Academy Of Country Music as Most Promising Female Vocalist and a Grammy Award as Best Country Vocalist. This proved to be only the beginning of a very exciting career. Her countless successes include three more Grammys, numerous Country Music Awards, American Music Awards and Peoples Choice Awards, five #1 hits including “Physical,” which topped the charts for ten consecutive weeks, and 15 top 10 singles. In 1978, her co-starring role with John Travolta in “Grease” catapulted Olivia into super- stardom. -

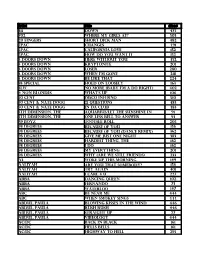

Music List (PDF)

Artist Title disc# 311 Down 475 702 Where My Girls At? 503 20 fingers short dick man 482 2pac changes 491 2Pac California Love 152 2Pac How Do You Want It 152 3 Doors Down Here Without You 452 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 201 3 doors down loser 280 3 Doors Down when I'm gone 218 3 Doors Down Be Like That 224 38 Special Hold On Loosely 163 3lw No more (baby I'm a do right) 402 4 Non Blondes What's Up 106 50 Cent Disco Inferno 510 50 cent & nate dogg 21 questions 483 50 cent & nate dogg in da club 483 5th Dimension, The aquarius/let the sunshine in 91 5th Dimension, The One Less Bell To Answer 93 69 Boyz Tootsee Roll 205 98 Degrees Because Of You 156 98 Degrees Because Of You (Dance Remix) 362 98 degrees Give me just one Night 383 98 Degrees Hardest Thing, the 162 98 Degrees I Do 162 98 Degrees My Everything 201 98 Degrees Why (Are We Still Friends) 233 A3 Woke Up This Morning 149 Aaliyah Are You That Somebody? 156 aaliyah Try again 401 Aaliyah I Care 4 U 227 Abba Dancing Queen 102 ABBA FERNANDO 73 ABBA Waterloo 147 ABC Be Near Me 444 ABC When Smokey Sings 444 ABDUL, PAULA Blowing Kisses In The Wind 446 ABDUL, PAULA Rush Rush 446 ABDUL, PAULA STRAIGHT UP 27 ABDUL, PAULA Vibeology 444 AC/DC Back In Black 161 AC/DC Hells Bells 161 AC/DC Highway To Hell 295 AC/DC Stiff Upper Lip 295 AC/DC Whole Lotta Rosie 295 AC/dc You shook me all night long 108 Ace Of Base Beautiful Life 8 Ace of Base Don't Turn Around 154 Ace Of Base Sign, The 206 AD LIBS BOY FROM NEW YORK CITY, THE 49 adam ant goody two shoes 108 ADAMS, BRYAN (EVERYTHING I DO) I DO IT FOR YOU -

Hopelessly Devoted by Elise Greig with Contributions from Nick Backstrom

Hopelessly Devoted by Elise Greig with contributions from Nick Backstrom A Playlab Indie Publication Contents Publication and Copyright Information 3 Introduction & Acknowledgements — Elise Greig 4 First Production Details 5 Production Photos 6 Hopelessly Devoted 8 Biography — Elise Greig 80 Song Credits 81 Teachers’ Notes 83 Publication and Copyright Information Performance Rights Any performance or public reading of any text in this volume is forbidden unless a licence has been received from the author or the author’s agent. The purchase of this book in no way gives the purchaser the right to perform the play in public, whether by means of a staged production or as a reading. Inquiries concerning performance rights, publication, translation or recording rights should be addressed to: Playlab, PO Box 3701, South Brisbane B.C, Qld 4101. Email: [email protected] Copyright This book is copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of study, research or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part may be reproduced by any process without written permission. For education purposes the Australian Copyright Act 1968 (Act) allows a maximum of one chapter or 10% of this book, whichever is greater to be copied, but only if the institution or educator is covered by a Copyright Agency Limited (CAL) licence. All inquiries should be made to the publisher at the address above. Copy Licences To print copies of this work, purchase a Copy Licence from the reseller from whom you originally bought this work or directly from Playlab at the address above. These Licences grant the right to print up to thirty copies. -

Songs by Artist

Songs by Artist Title DiscID Title DiscID 10 Years 2 Pac & Eric Will Wasteland SC8966-13 Do For Love MM6299-09 10,000 Maniacs 2 Pac & Notorious Big Because The Night SC8113-05 Runnin' SC8858-11 Candy Everybody Wants DK082-04 2 Unlimited Like The Weather MM6066-07 No Limits SF006-05 More Than This SC8390-06 20 Fingers These Are The Days SC8466-14 Short Dick Man SC8746-14 Trouble Me SC8439-03 3 am 100 Proof Aged In Soul Busted MRH10-07 Somebody's Been Sleeping SC8333-09 3 Colours Red 10Cc Beautiful Day SF130-13 Donna SF090-15 3 Days Grace Dreadlock Holiday SF023-12 Home SIN0001-04 I'm Mandy SF079-03 Just Like You SIN0012-08 I'm Not In Love SC8417-13 3 Doors Down Rubber Bullets SF071-01 Away From The Sun SC8865-07 Things We Do For Love SFMW832-11 Be Like That MM6345-09 Wall Street Shuffle SFMW814-01 Behind Those Eyes SC8924-02 We Do For Love SC8456-15 Citizen Soldier CB30069-14 112 Duck & Run SC3244-03 Come See Me SC8357-10 Here By Me SD4510-02 Cupid SC3015-05 Here Without You SC8905-09 Dance With Me SC8726-09 It's Not My Time (I Won't Go) CB30070-01 It's Over Now SC8672-15 Kryptonite SC8765-03 Only You SC8295-04 Landing In London CB30056-13 Peaches & Cream SC3258-02 Let Me Be Myself CB30083-01 Right Here For You PHU0403-04 Let Me Go SC2496-04 U Already Know PHM0505U-07 Live For Today SC3450-06 112 & Ludacris Loser SC8622-03 Hot & Wet PHU0401-02 Road I'm On SC8817-10 12 Gauge Train CB30075-01 Dunkie Butt SC8892-04 When I'm Gone SC8852-11 12 Stones 3 Doors Down & Bob Seger Crash TU200-04 Landing In London CB30056-13 Far Away THR0411-16 3 Of A Kind We Are One PHMP1008-08 Baby Cakes EZH038-01 1910 Fruitgum Co. -

Olivia Newton-John Soul Kiss Mp3, Flac, Wma

Olivia Newton-John Soul Kiss mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Electronic / Pop Album: Soul Kiss Country: Brazil Released: 1985 Style: Synth-pop MP3 version RAR size: 1631 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1629 mb WMA version RAR size: 1277 mb Rating: 4.3 Votes: 983 Other Formats: TTA WAV MIDI FLAC ADX DXD AC3 Tracklist A Soul Kiss (Extended Remix Version) 6:38 B1 Soul Kiss (Dub Mix) 6:15 B2 Electric 3:45 Companies, etc. Manufactured By – Fonobrás, Distribuidora Fonográfica Brasileira Ltda. Distributed By – Fonobrás, Distribuidora Fonográfica Brasileira Ltda. Licensed From – Polygram do Brasil Ltda. Credits Management – Roger Davies Management Inc. Producer – John Farrar Remix – Steve Thompson & Michael Barbiero Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Soul Kiss (7", 884 090-7 Olivia Newton-John Mercury 884 090-7 Netherlands 1985 Single) Mercury, 884090-7 Olivia Newton-John Soul Kiss (7") 884090-7 Portugal 1985 Polygram Soul Kiss (12", X14254 Olivia Newton-John Interfusion X14254 Australia 1985 Maxi, Ltd) Beso Del Alma (7", 1446 Olivia Newton-John Mercury 1446 Mexico 1985 Single, Promo) Soul Kiss (7", MCA-52686 Olivia Newton-John MCA Records MCA-52686 US 1985 Promo) Related Music albums to Soul Kiss by Olivia Newton-John Olivia Newton-John - What Is Life Olivia Newton-John - Olivia's Greatest Hits Vol. 2 Olivia Newton-John - Let Me Be There / Maybe Then I'll Think Of You Olivia - Soul Kiss Videosingles John Travolta & Olivia Newton-John - You're The One That I Want Olivia Newton-John - The Rumour Olivia Newton-John - Don't Stop Believin' Olivia Newton-John - Toughen Up Olivia Newton-John - Banks Of The Ohio Andy Gibb & Olivia Newton-John - Rest Your Love On Me A While. -

Songs by Artist

Songs By Artist Artist Song Title Disc # Artist Song Title Disc # (children's Songs) I've Been Working On The 04786 (christmas) Pointer Santa Claus Is Coming To 08087 Railroad Sisters, The Town London Bridge Is Falling 05793 (christmas) Presley, Blue Christmas 01032 Down Elvis Mary Had A Little Lamb 06220 (christmas) Reggae Man O Christmas Tree (o 11928 Polly Wolly Doodle 07454 Tannenbaum) (christmas) Sia Everyday Is Christmas 11784 She'll Be Comin' Round The 08344 Mountain (christmas) Strait, Christmas Cookies 11754 Skip To My Lou 08545 George (duet) 50 Cent & Nate 21 Questions 00036 This Old Man 09599 Dogg Three Blind Mice 09631 (duet) Adams, Bryan & When You're Gone 10534 Twinkle Twinkle Little Star 09938 Melanie C. (christian) Swing Low, Sweet Chariot 09228 (duet) Adams, Bryan & All For Love 00228 (christmas) Deck The Halls 02052 Sting & Rod Stewart (duet) Alex & Sierra Scarecrow 08155 Greensleeves 03464 (duet) All Star Tribute What's Goin' On 10428 I Saw Mommy Kissing 04438 Santa Claus (duet) Anka, Paul & Pennies From Heaven 07334 Jingle Bells 05154 Michael Buble (duet) Aqua Barbie Girl 00727 Joy To The World 05169 (duet) Atlantic Starr Always 00342 Little Drummer Boy 05711 I'll Remember You 04667 Rudolph The Red-nosed 07990 Reindeer Secret Lovers 08191 Santa Claus Is Coming To 08088 (duet) Balvin, J. & Safari 08057 Town Pharrell Williams & Bia Sleigh Ride 08564 & Sky Twelve Days Of Christmas, 09934 (duet) Barenaked Ladies If I Had $1,000,000 04597 The (duet) Base, Rob & D.j. It Takes Two 05028 We Wish You A Merry 10324 E-z Rock Christmas (duet) Beyonce & Freedom 03007 (christmas) (duets) Year Snow Miser Song 11989 Kendrick Lamar Without A Santa Claus (duet) Beyonce & Luther Closer I Get To You, The 01633 (christmas) (musical) We Need A Little Christmas 10314 Vandross Mame (duet) Black, Clint & Bad Goodbye, A 00674 (christmas) Andrew Christmas Island 11755 Wynonna Sisters, The (duet) Blige, Mary J.