Download Original Attachment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Dawn in Erewhon"

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons CUREJ - College Undergraduate Research Electronic Journal College of Arts and Sciences December 2007 Dimensions of Erewhon: The Modern Orpheus in Guy Davenport's "The Dawn in Erewhon" Patrick Dillon [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/curej Recommended Citation Dillon, Patrick, "Dimensions of Erewhon: The Modern Orpheus in Guy Davenport's "The Dawn in Erewhon"" 10 December 2007. CUREJ: College Undergraduate Research Electronic Journal, University of Pennsylvania, https://repository.upenn.edu/curej/23. Revised version, posted 10 December 2007. This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/curej/23 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Dimensions of Erewhon: The Modern Orpheus in Guy Davenport's "The Dawn in Erewhon" Abstract In "The Dawn in Erewhon", the concluding novella of Tatlin!, Guy Davenport explores the myth of Orpheus in the context of two storylines: Adriaan van Hovendaal, a thinly veiled version of Ludwig Wittgenstein, and an updated retelling of Samuel Butler's utopian novel Erewhon. Davenport tells the story in a disjunctive style and uses the Orpheus myth as a symbol to refer to a creative sensibility that has been lost in modern technological civilization but is recoverable through art. Keywords Charles Bernstein, Bernstein, Charles, English, Guy Davenport, Davenport, Orpheus, Tatlin, Dawn in Erewhon, Erewhon, ludite, luditism Comments Revised version, posted 10 December 2007. This article is available at ScholarlyCommons: https://repository.upenn.edu/curej/23 Dimensions of Erewhon The Modern Orpheus in Guy Davenport’s “The Dawn in Erewhon” Patrick Dillon Introduction: The Assemblage Style Although Tatlin! is Guy Davenport’s first collection of fiction, it is the work of a fully mature artist. -

Witnessing the Exterior| Blanchot and the Impossibility of Writing

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1991 Witnessing the exterior| Blanchot and the impossibility of writing Philip John Maloney The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Maloney, Philip John, "Witnessing the exterior| Blanchot and the impossibility of writing" (1991). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 4106. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/4106 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Maureen and Mike MANSFIELD LIBRARY Copying allowed as provided under provisions of the Fair Use Section of the U.S. COPYRIGHT LAW, 1976. Any copying for commercial purposes or financial gain may be undertaken only with the author's written consent. MontanaUniversity of Witnessing The Exterior Blanchot and the Impossibility of Writing By Philip John Maloney B.A., University of Montana, 1989 Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts University of Montana 1991 Approved by hair, Board of Examiners iean. Graduate ScHoi /??/ UMI Number: EP35377 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. -

Présentation Creative Professional Codevelopment CPCD 29.11.16

THE ORPHEUS EXPERIENCE - PILOT Orpheus, the Seal of the Eternal Couple Pitch Materials Alain Amouyal – Creator, Writer, Composer Live and Filmed Multi-Media & Virtual Reality Stand-alone PILOT for 15 Episode Series LOGLINE – An enduring, classical love story offers entertainment, insight, healing, wisdom, and transformation through music, dance, filmed imagery, live performance, and virtual reality. PITCH 1. The ancient Greek story of Orpheus and Eurydice is one of the most transformative of all Myths, from the very intimate and personal level to the societal and species level. 2. In this reinterpretation of the Orpheus Myth, adapted to the 21st century, its message of love, pride, jealousy, temptation, the fall into darkness, the difficult road to redemption, and the ultimate reunion of separated parts of the self, in the guise of the tragic and then transformed lovers, holds important truths for us all.The beauty of the music and visuals captures the emotions and the imagination and resonates with the audience long after the initial immersive multi-media experience. When the gaze of Orpheus Borrows the eyes of an ordinary man… And Life invites him to go back To the origins of his break with Eurydice, To see his mistakes in the mirror of his past, And to understand that he can make them good… Then the Man-Orpheus, on the edge of the known world, Explores the deep layers of his cerebral earth, And discovers Eurydice hidden in his own depth. SYNOPSIS These days when both conquering and surrendering are disputably prime aspects of romantic and social relationships, we need to take a good long look at the energetic dynamics and how they can best serve us all, from the very practical to the very spiritual. -

The Story of Orpheus and Eurydice in Coetzee and Rilke

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Debrecen Electronic Archive ACTA UNIVERSITATIS SAPIENTIAE, PHILOLOGICA, 8, 1 (2016) 41–48 DOI: 10.1515/ausp-2016-0003 The Story of Orpheus and Eurydice in Coetzee and Rilke Ottilia VERES Partium Christian University (Oradea, Romania) Department of English Language and Literature [email protected] Abstract. J. M. Coetzee’s The Master of Petersburg (1994) is a text about a father (Dostoevsky) mourning the death of his son. I am interested in the presence and meaning of the myth of Orpheus and Eurydice in the novel, compared to the meaning of the myth in R. M. Rilke’s poem “Orpheus. Eurydice. Hermes.” (1904). I read the unaccomplished encounter between Orpheus and Eurydice as a story that portrays the failed intersubjectity plot of Coetzee’s novel(s). Following Blanchot’s reading of the myth, I examine the contrasting Orphean and Eurydicean conducts – Orpheus desiring but, at the same time, destroying the other and Eurydice declining the other’s approach. I argue that Orpheus’s and Eurydice’s contrasting behaviours can be looked at as manifestations of a failure of love, one for its violence, the other for its neglect, and thus the presence of the myth in The Master of Petersburg is meaningful in what it says about the theme of intersubjectivity in Coetzee’s oeuvre. Keywords: Orpheus, Eurydice, encounter, intersubjectivity. J. M. Coetzee’s seventh novel, The Master of Petersburg (1994), is a novel about the trauma of losing a son; it is a mourning text both in the sense that in it the protagonist Dostoevsky tries to work through the trauma of loss (and through him Coetzee tries to work through the trauma of the loss of his own son1) and in the sense that the novel textually performs the work of mourning by trying – and failing – to understand this loss. -

The Anti-Orpheus: Queering Myth in Ducastel Et Martineau's Théo Et

Studies in 20th & 21st Century Literature Volume 42 Issue 2 Article 4 February 2018 The Anti-Orpheus: Queering Myth in Ducastel et Martineau’s Théo et Hugo dans le même bateau (Paris 05:59) Todd W. Reeser University of Pittsburgh, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://newprairiepress.org/sttcl Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons, and the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Studies Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Reeser, Todd W. (2018) "The Anti-Orpheus: Queering Myth in Ducastel et Martineau’s Théo et Hugo dans le même bateau (Paris 05:59)," Studies in 20th & 21st Century Literature: Vol. 42: Iss. 2, Article 4. https://doi.org/10.4148/2334-4415.1989 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by New Prairie Press. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studies in 20th & 21st Century Literature by an authorized administrator of New Prairie Press. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Anti-Orpheus: Queering Myth in Ducastel et Martineau’s Théo et Hugo dans le même bateau (Paris 05:59) Abstract Olivier Ducastel and Jacques Martineau’s 2016 film Théo et Hugo dans le même bateau (Paris 05:59: Théo & Hugo) concludes on an Orphic note, inviting a consideration of the entire film as based on the myth of Orpheus and Eurydice. The film appropriates but also radically transforms elements of the foundational myth—including especially Orpheus’s turn to pederasty in Ovid’s Latin version—crafting a queer love story based on potentiality out of the tragedy of the heterosexual love story. -

The Visual Craft of Old English Verse: Mise-En-Page in Anglo-Saxon Manuscripts

The visual craft of Old English verse: mise-en-page in Anglo-Saxon manuscripts Rachel Ann Burns UCL PhD in English Language and Literature 1 I, Rachel Ann Burns confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. Rachel Ann Burns 2 Table of Contents Abstract 8 Acknowledgements 10 Abbreviations 12 List of images and figures 13 List of tables 17 CHAPTER ONE: Introduction 18 Organisation of the page 26 Traditional approaches to Old English verse mise-en-page 31 Questions and hypotheses 42 Literature review and critical approaches 43 Terminology and methodologies 61 Full chapter plan 68 CHAPTER TWO: Demarcation of the metrical period in the Latin verse texts of Anglo-Saxon England 74 Latin verse on the page: classical and late antiquity 80 Latin verse in early Anglo-Saxon England: identifying sample sets 89 New approach 92 Identifying a sample set 95 Basic results from the sample set 96 Manuscript origins and lineation 109 Order and lineation: acrostic verse 110 3 Order and lineation: computistical verse and calendars 115 Conclusions from the sample set 118 Divergence from Old English 119 Learning Latin in Anglo-Saxon England: the ‘shape’ of verse 124 Contrasting ‘shapes’: Latin and Old English composition 128 Hybrid layouts, and the failure of lineated Old English verse 137 Correspondences with Latin rhythmic verse 145 Conclusions 150 CHAPTER THREE: Inter-word Spacing in Beowulf and the neurophysiology of scribal engagement with Old English verse 151 Thesis and hypothesis 152 Introduction of word-spacing in the Latin West 156 Previous scholarship on the significance of inter-word spacing 161 Robert D. -

Download Original Attachment

FACULTY OF ENGLISH LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE M.St./M.Phil. English Course Details 2015-16 Further programnme information is available in the M.St./M.Phil. Handbook CONTENTS INTRODUCTION TO THE… M.St. in English Literature (by period, English and American and World Literatures) 4 M.St. in English Language 6 M.Phil. in English (Medieval Studies) 8 STRAND SPECIFIC COURSE DESCRIPTIONS (A- and Hilary Term B- Courses) M.St. 650-1550/first year M.Phil. (including Michaelmas Term B-Course) 9 M.St. 1550-1700 18 M.St. 1700-1830 28 M.St. 1830-1914 35 M.St. 1900-present 38 M.St. English and American Studies 42 M. St. World Literatures in English 46 M.St. English Language (including Michaelmas Term B-Course) 51 B-COURSE, POST-1550 - MICHAELMAS TERM 62 Material Texts, 1550-1830 63 Material Texts, 1830-1914 65 Material Texts, Post-1900 66 Transcription Classes 71 C-COURSES - MICHAELMAS TERM You can select any C-Course The Age of Alfred 72 The Language of Middle English Literature 73 Older Scots Literature 74 Tragicomedy from the Greeks to Shakespeare 77 Documents of Theatre History 80 Romantic to Victorian: Wordsworth’s Writings 1787-1845 85 Literature in Brief 86 Women’s Poetry 1700-1830 89 Aestheticism, Decadence and the Fin de Siècle 91 Late Modernist Poetry in America and Britain 93 High Modernism at play: Modernists and Children’s Literature 94 Reading Emerson 95 Theories of World Literature 96 Legal Fictions: Law in Postcolonial and World Literature 99 Lexicography 101 2 C-COURSES - HILARY TERM You can select any C-Course The Anglo-Saxon Riddle -

Zion Assessment List 2019 (PDF)

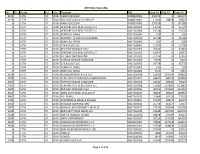

2019 Zion Township No. Dir. Street Suf. City Taxpayer PIN Land AV Bldg AV Total AV 3101 12TH ST ZION NANCY DE LEON 0408325001 242572 0 242572 3113 12TH ST ZION WALLACE A & LOIS I STREICH 0408324002 11024 28618 39642 0 13TH ST ZION NANCY DE LEON 0408324003 197188 0 197188 0 16TH ST ZION VENTURE ONE REAL ESTATE LLC 0417101014 11722 0 11722 0 16TH ST ZION VENTURE ONE REAL ESTATE LLC 0417101006 15224 0 15224 0 16TH ST ZION DONALD J CRAIG 0417101004 156 0 156 0 16TH ST ZION DOMINIC & SALONA SCARDINA 0417102016 26708 0 26708 0 16TH ST ZION DONALD J CRAIG 0417101003 530 0 530 0 16TH ST ZION 173 & LEWIS LLC 0417103001 11550 0 11550 0 16TH ST ZION RED DOT STORAGE II LLC 0417102005 32447 0 32447 0 16TH ST ZION VENTURE ONE REAL ESTATE LLC 0417101015 16957 0 16957 0 16TH ST ZION STEDAR CORPORATION 0417102013 27314 0 27314 0 16TH ST ZION PATRICK HAGGIE, MANAGER 0417101009 5975 0 5975 0 16TH ST ZION 173 & LEWIS LLC 0417103002 36778 0 36778 0 16TH ST ZION DONALD J CRAIG 0417101005 330 0 330 0 16TH ST ZION DONALD J CRAIG 0417101002 1512 0 1512 3140 16TH ST ZION SHERIDAN PROPERTIES, LLC 0417100008 61466 267344 328810 3200 16TH ST ZION 3200-16TH ST BUILDING CORPORATION 0417101011 64831 84973 149804 3204 16TH ST ZION PATRICK HAGGIE, MANAGER 0417101010 18701 60326 79027 3300 16TH ST ZION VENTURE ONE REAL ESTATE LLC 0417101008 51282 561605 612887 3303 16TH ST ZION RED DOT STORAGE II LLC 0417102004 40991 570262 611253 3311 16TH ST ZION ABRA AUTO BODY & GLASS LP 0417102017 40862 89125 129987 3401 16TH ST ZION YLLI PLAKU 0417102015 22006 50213 72219 3403 16TH -

Oath-Taking and Oath-Breaking in Medieval Lceland and Anglo-Saxon England

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Dissertations Graduate College 12-2014 Bound by Words: Oath-taking and Oath-breaking in Medieval lceland and Anglo-Saxon England Gregory L. Laing Western Michigan University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/dissertations Part of the English Language and Literature Commons, Medieval History Commons, and the Medieval Studies Commons Recommended Citation Laing, Gregory L., "Bound by Words: Oath-taking and Oath-breaking in Medieval lceland and Anglo-Saxon England" (2014). Dissertations. 382. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/dissertations/382 This Dissertation-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BOUND BY WORDS: THE MOTIF OF OATH-TAKING AND OATH-BREAKING IN MEDIEVAL ICELAND AND ANGLO-SAXON ENGLAND by Gregory L. Laing A Dissertation submitted to the Graduate College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy English Western Michigan University December 2014 Doctoral Committee: Jana K. Schulman, Ph.D., Chair Eve Salisbury, Ph.D. Larry Hunt, Ph.D. Paul E. Szarmach, Ph.D. BOUND BY WORDS: THE MOTIF OF OATH-TAKING AND OATH-BREAKING IN MEDIEVAL ICELAND AND ANGLO-SAXON ENGLAND Gregory L. Laing, Ph.D. Western Michigan University, 2014 The legal and literary texts of early medieval England and Iceland share a common emphasis on truth and demonstrate its importance through the sheer volume of textual references. -

ACCS/ACAS/IICJ 2016 Art Center Kobe, Japan Official Conference Proceedings Iafor ISSN: 2187 - 4751

The International Academic Forum ACCS/ACAS/IICJ 2016 Art Center Kobe, Japan Official Conference Proceedings iafor ISSN: 2187 - 4751 “To Open Minds, To Educate Intelligence, To Inform Decisions” The International Academic Forum provides new perspectives to the thought-leaders and decision-makers of today and tomorrow by offering constructive environments for dialogue and interchange at the intersections of nation, culture, and discipline. Headquartered in Nagoya, Japan, and registered as a Non-Profit Organization 一般社( 団法人) , IAFOR is an independent think tank committed to the deeper understanding of contemporary geo-political transformation, particularly in the Asia Pacific Region. INTERNATIONAL INTERCULTURAL INTERDISCIPLINARY iafor The Executive Council of the International Advisory Board IAB Chair: Professor Stuart D.B. Picken Mr Mitsumasa Aoyama Professor June Henton Professor Baden Offord Director, The Yufuku Gallery, Tokyo, Japan Dean, College of Human Sciences, Auburn University, Professor of Cultural Studies and Human Rights & Co- USA Director of the Centre for Peace and Social Justice Professor Tien-Hui Chiang Southern Cross University, Australia Professor and Chair, Department of Education Professor Michael Hudson National University of Tainan, Taiwan/Chinese Taipei President of The Institute for the Study of Long-Term Professor Frank S. Ravitch Economic Trends (ISLET) Professor of Law & Walter H. Stowers Chair in Law Professor Don Brash Distinguished Research Professor of Economics, The and Religion, Michigan State University College of Law Former Governor of the Reserve Bank, New Zealand University of Missouri, Kansas City Former Leader of the New National Party, New Professor Richard Roth Zealand Professor Koichi Iwabuchi Senior Associate Dean, Medill School of Journalism, Adjunct Professor, AUT, New Zealand & La Trobe Professor of Media and Cultural Studies & Director of Northwestern University, Qatar University, Australia the Monash Asia Institute, Monash University, Australia Professor Monty P. -

2019 Unclaimed Property Report

NOTICE TO OWNERS OF ABANDONED PROPERTY: 2019 UNCLAIMED PROPERTY REPORT State Treasurer John Murante 402-471-8497 | 877-572-9688 treasurer.nebraska.gov Unclaimed Property Division 809 P Street Lincoln, NE 68508 Dear Nebraskans, KUHLMANN ORTHODONTICS STEINSLAND VICKI A WITT TOM W KRAMER TODD WINTERS CORY J HART KENNETH R MOORE DEBRA S SWANSON MATHEW CLAIM TO STATE OF NEBRASKA FOR UNCLAIMED PROPERTY Reminder: Information concerning the GAYLE Y PERSHING STEMMERMAN WOLFE BRIAN LOWE JACK YOUNG PATRICK R HENDRICKSON MOORE KEVIN SZENASI CYLVIA KUNSELMAN ADA E PAINE DONNA CATHERNE COLIN E F MR. Thank you for your interest in the 2019 Property ID Number(s) (if known): How did you become aware of this property? WOODWARD MCCASLAND TAYLORHERDT LIZ “Claimant” means person claiming property. amount or description of the property and LARA JOSE JR PALACIOS AUCIN STORMS DAKOTA R DANNY VIRGILENE HENDRICKSON MULHERN LINDA J THOMAS BURDETTE Unclaimed Property Newspaper Publication BOX BUTTE Unclaimed Property Report. Unclaimed “Owner” means name as listed with the State Treasurer. LE VU A WILMER DAVID STORY LINDA WURDEMAN SARAH N MUNGER TIMOTHY TOMS AUTO & CYCLE Nebraska State Fair the name and address of the holder may PARR MADELINE TIFFANY ADAMS MICHAEL HENZLER DEBRA J property can come in many different Husker Harvest Days LEFFLER ROBERT STRATEGIC PIONEER BANNER MUNRO ALLEN W REPAIR Claimant’s Name and Present Address: Claimant is: LEMIRAND PATTNO TOM J STREFF BRIAN WYMORE ERMA M BAKKEHAUG HENZLER RONALD L MURPHY SHIRLEY M TOOLEY MICHAEL J Other Outreach -

Old English Newsletter

OLD ENGLISH NEWSLETTER Published for !e Old English Division of the Modern Language Association of America by !e Medieval Institute, Western Michigan University and its Richard Rawlinson Center for Anglo-Saxon Studies Editor: R.M. Liuzza Associate Editors: Daniel Donoghue !omas Hall VOLUME NUMBER FALL ISSN - O!" E#$!%&' N()&!(**(+ Volume "# Number $ Fall %&&' Editor Publisher R. M. Liuzza Paul E. Szarmach Department of English Medieval Institute The University of Tennessee Western Michigan University "&$ McClung Tower $#&" W. Michigan Ave. Knoxville, TN "(##)-&*"& Kalamazoo, MI *#&&+-'*"% Associate Editors Year’s Work in Old English Studies OEN Bibliography Daniel Donoghue Thomas Hall Department of English Department of English (M/C $)%) Harvard University University of Illinois at Chicago Barker Center / $% Quincy St. )&$ S. Morgan Street Cambridge MA &%$"+ Chicago, IL )&)&(-($%& Assistant to the Editor: Tara Lynn Assistant to the Publisher: David Clark Subscriptions: The rate for institutions is ,%& -. per volume, current and past volumes, except for volumes $ and %, which are sold as one. The rate for individuals is ,$' -. per volume, but in order to reduce administrative costs the editors ask individuals to pay for two volumes (currently "+ & "#) at one time at the discounted rate of ,%'. Correspondence: General correspondence regarding OEN should be addressed to the Editor; correspondence regard- ing the Year’s Work and the annual Bibliography should be sent to the respective Associate Editors. Correspondence regarding business matters and subscriptions should be sent to the Publisher. Submissions: The Old English Newsletter is a referreed periodical. Solicited and unsolicited manuscripts (except for independent reports and news items) are reviewed by specialists in anonymous reports. Scholars can assist the work of OEN by sending offprints of articles, and notices of books or monographs, to the Edi- tor.