Pinball Wizard at Full Tilt

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NJSO Welcomes Michael Cavanaugh for Classic Rock Program Featuring Greatest Hits of Elton John and More

New Jersey Symphony Orchestra Press Contact: Victoria McCabe, NJSO Senior Manager of Public Relations & Communications 973.735.1715 | [email protected] State Theatre Press Contact: Kelly Blithe, State Theatre Director of Communications 732.247.7200, ext. 542 | [email protected] www.njsymphony.org/pressroom FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE NJSO welcomes Michael Cavanaugh for classic rock program featuring greatest hits of Elton John and more Cavanaugh, original star of Broadway’s Movin’ Out, takes center stage Program features ‘Tiny Dancer,’ ‘Bennie and the Jets,’ ‘Rocket Man,’ ‘Live and Let Die,’ ‘Pinball Wizard’ and more classic rock favorites NJSO Accents include pre-concert sing-alongs State Theatre co-presents New Brunswick performance Sat, Nov 12, at NJPAC in Newark Sun, Nov 13, at State Theatre in New Brunswick NEWARK, NJ (October 6, 2016)—Broadway star Michal Cavanaugh, of Movin’ Out fame, joins the New Jersey Symphony Orchestra for a program of hits from Elton John and other classic rock legends, November 12–13 in Newark and New Brunswick. Cavanaugh performs Elton John hits like “Tiny Dancer,” “Bennie and the Jets” and “Rocket Man,” as well as classics like “Live and Let Die” and “Pinball Wizard,” in a high-energy show led by frequent NJSO guest conductor and audience favorite Thomas Wilkins. “Michael Cavanaugh with the NJSO: Greatest Hits of Elton John and More” is the first of five 2016–17 NJSO Pops programs. Performances take place on Saturday, November 12, at 8 pm at the New Jersey Performing Arts Center (NJPAC) in Newark and Sunday, November 13, at 3 pm at the State Theatre in New Brunswick. -

Pin Golf Score Sheet Name: # Pinball Novice Average Pro Score 1

Pin Golf Score Sheet Pin Golf Score Sheet Name: Name: # Pinball Novice Average Pro Score # Pinball Novice Average Pro Score Lite ABCD A-D + Bonus A-D + Bonus + Lite ABCD A-D + Bonus A-D + Bonus + Paddock 1: 1: Finish Race Paddock 1: 1: Finish Race 1 2: 2:: 1: 1 2: 2:: 1: (W ’69) 3: 2: (W ’69) 3: 2: 3: 3: 3: 3: Lite ABCD A-D + Bonus A-D + Bonus + Lite ABCD A-D + Bonus A-D + Bonus + Centigrade 37 1: 1: Adv Therm Centigrade 37 1: 1: Adv Therm 2 2: 2:: 1: 2 2: 2:: 1: (G ’77) 3: 3: 2: (G ’77) 3: 3: 2: 3: 3: Lite ABC A-C + Bonus A-C + Bonus + Lite ABC A-C + Bonus A-C + Bonus + Joker Poker 1: 1: Cards Joker Poker 1: 1: Cards 3 2: 2:: 1: 3 2: 2:: 1: (G ’78) 3: 3: 2: (G ’78) 3: 3: 2: 3: 3: 50,000 1 million 2 million 50,000 1 million 2 million Cyclone 1: 1: 1: Cyclone 1: 1: 1: 4 4 (W ’88) 2: 2: 2: (W ’88) 2: 2: 2: 3: 3: 3: 3: 3: 3: 1.25 million 2.5 million 5 million 1.25 million 2.5 million 5 million Bad Cats 1: 1: 1: Bad Cats 1: 1: 1: 5 5 (W ’89) 2: 2: 2: (W ’89) 2: 2: 2: 3: 3: 3: 3: 3: 3: 625,000 1.25 million 2.5 million 625,000 1.25 million 2.5 million Black Knight 2K 1: 1: 1: Black Knight 2K 1: 1: 1: 6 6 (W ’89) 2: 2: 2: (W ’89) 2: 2: 2: 3: 3: 3: 3: 3: 3: 750,000 1.5 million 3 million 750,000 1.5 million 3 million Elvira ATPM 1: 1: 1: Elvira ATPM 1: 1: 1: 7 7 (B ’89) 2: 2: 2: (B ’89) 2: 2: 2: 3: 3: 3: 3: 3: 3: 1.5 million 3 million 6 million 1.5 million 3 million 6 million 1: 1: 1: 1: 1: 1: 8 Diner (W ’90) 2: 2: 2: 8 Diner (W ’90) 2: 2: 2: 3: 3: 3: 3: 3: 3: 1.25 million 2.5 million 5 million 1.25 million 2.5 million 5 million Addams Family -

Pinball Game List

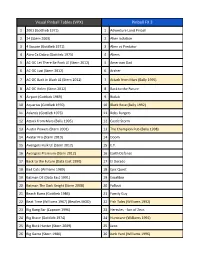

Visual Pinball Tables (VPX) Pinball FX 3 1 2001 (Gottlieb 1971) 1 Adventure Land Pinball 2 24 (Stern 2009) 2 Alien Isolation 3 4 Square (Gottlieb 1971) 3 Alien vs Predator 4 Abra Ca Dabra (Gottlieb 1975) 4 Aliens 5 AC-DC Let There Be Rock LE (Stern 2012) 5 American Dad 6 AC-DC Luci (Stern 2012) 6 Archer 7 AC-DC Back in Black LE (Stern 2012) 7 Attack from Mars (Bally 1995) 8 AC-DC Helen (Stern 2012) 8 Back to the Future 9 Airport (Gottlieb 1969) 9 Biolab 10 Aquarius (Gottlieb 1970) 10 Black Rose (Bally 1992) 11 Atlantis (Gottlieb 1975) 11 Bobs Burgers 12 Attack from Mars (Bally 1995) 12 Castle Storm 13 Austin Powers (Stern 2001) 13 The Champion Pub (Bally 1998) 14 Avatar Pro (Stern 2010) 14 Doom 15 Avengers Hulk LE (Stern 2012) 15 E.T. 16 Avengers Premium (Stern 2012) 16 Earth Defense 17 Back to the Future (Data East 1990) 17 El Dorado 18 Bad Cats (Williams 1989) 18 Epic Quest 19 Batman DE (Data East 1991) 19 Excalibur 20 Batman The Dark Knight (Stern 2008) 20 Fallout 21 Beach Bums (Gottlieb 1986) 21 Family Guy 22 Beat Time (Williams 1967) (Beatles MOD) 22 Fish Tales (Williams 1992) 23 Big Bang Bar (Capcom 1996) 23 Hercules - Son of Zeus 24 Big Brave (Gottlieb 1974) 24 Hurricane (Williams 1991) 25 Big Buck Hunter (Stern 2009) 25 Jaws 26 Big Game (Stern 1980) 26 Junk Yard (Williams 1996) Visual Pinball Tables (VPX) Pinball FX 3 27 Big Guns (Williams 1987) 27 Jurassic Park 28 Black Knight (Williams 1980) 28 Jurassic Park Pinball Mayhem 29 Black Knight 2000 (Williams 1989) 29 Jurassic World 30 Black Rose (Bally 1992) 30 Mars 31 Blue Note (Gottlieb 1979) 31 Marvel - Age of Ultron 32 Bram Stoker's Dracula (Williams 1993) 32 Marvel - Ant-Man 33 Bronco (Gottlieb 1977) 33 Marvel - Blade 34 Bubba the Redneck Werewolf (2018) 34 Marvel - Captain America 35 Buccaneer (Gottlieb 1976) 35 Marvel - Civil War 36 Buckaroo (Gottlieb 1965) 36 Marvel - Deadpool 37 Bugs Bunny B. -

1080-Pinballgamelist.Pdf

No. Table Name Table Type 1 12 Days Christmas VPX Table 2 2001 (Gottlieb 1971) VP 9 Table 3 24 (Stern 2009) VP 9 Table 4 250cc (Inder 1992) VP 9 Table 5 4 Roses (Williams 1962) VP 9 Table 6 4 Square (Gottlieb 1971) VP 9 Table 7 Aaron Spelling (Data East 1992) VP 9 Table 8 Abra Ca Dabra (Gottlieb 1975) VP 9 Table 9 ACDC (Stern 2012) VP 9 Table 10 ACDC Pro - PM5 (Stern 2012) PM5 Table 11 ACDC Pro (Stern 2012) VP 9 Table 12 Addams Family Golden (Williams 1994) VP 9 Table 13 Adventures of Rocky and Bullwinkle and Friends (Data East 1993) VP 9 Table 14 Aerosmith Future Table 15 Agents 777 (GamePlan 1984) VP 9 Table 16 Air Aces (Bally 1975) VP 9 Table 17 Airborne (Capcom 1996) VP 9 Table 18 Airborne Avenger (Atari 1977) VP 9 Table 19 Airport (Gottlieb 1969) VP 9 Table 20 Aladdin's Castle (Bally 1976) VP 9 Table 21 Alaska (Interflip 1978) VP 9 Table 22 Algar (Williams 1980) VP 9 Table 23 Ali (Stern 1980) VP 9 Table 24 Ali Baba (Gottlieb 1948) VP 9 Table 25 Alice Cooper Future Table 26 Alien Poker (Williams 1980) VP 9 Table 27 Alien Star (Gottlieb 1984) VP 9 Table 28 Alive! (Brunswick 1978) VPX Table 29 Alle Neune (NSM 1976) VP 9 Table 30 Alley Cats (Williams 1985) VP 9 Table 31 Alpine Club (Williams 1965) VP 9 Table 32 Al's Garage Band Goes On World Tour (Alivin G. 1992) VP 9 Table 33 Amazing Spiderman (Gottlieb 1980) VP 9 Table 34 Amazon Hunt (Gottlieb 1983) VP 9 Table 35 America 1492 (Juegos Populares 1986) VP 9 Table 36 Amigo (Bally 1973) VP 9 Table 37 Andromeda (GamePlan 1985) VP 9 Table 38 Animaniacs SE Future Table 39 Antar (Playmatic 1979) -

Dancing in My Underwear

Dancing in My Underwear The Soundtrack of My Life By Mike Morsch Copyright© 2012 Mike Morsch i Dancing in My Underwear With love for Judy, Kiley, Lexi, Kaitie and Kevin. And for Mom and Dad. Thanks for introducing me to some great music. Published by The Educational Publisher www.EduPublisher.com ISBN: 978-1-62249-005-9 ii Contents Foreword By Frank D. Quattrone 1 Chapters: The Association Larry Ramos Dancing in my underwear 3 The Monkees Micky Dolenz The freakiest cool “Purple Haze” 9 The Lawrence Welk Show Ken Delo The secret family chip dip 17 Olivia Newton-John Girls are for more than pelting with apples 25 Cheech and Chong Tommy Chong The Eighth-Grade Stupid Shit Hall of Fame 33 iii Dancing in My Underwear The Doobie Brothers Tom Johnston Rush the stage and risk breaking a hip? 41 America Dewey Bunnell Wardrobe malfunction: Right guy, right spot, right time 45 Three Dog Night Chuck Negron Elvis sideburns and a puka shell necklace 51 The Beach Boys Mike Love Washing one’s hair in a toilet with Comet in the middle of Nowhere, Minnesota 55 Hawaii Five-0 Al Harrington Learning the proper way to stretch a single into a double 61 KISS Paul Stanley Pinball wizard in a Mark Twain town 71 The Beach Boys Bruce Johnston Face down in the fields of dreams 79 iv Dancing in My Underwear Roy Clark Grinnin’ with the ole picker and grinner 85 The Boston Pops Keith Lockhart They sound just like the movie 93 The Beach Boys Brian Wilson Little one who made my heart come all undone 101 The Bellamy Brothers Howard Bellamy I could be perquaded 127 The Beach Boys Al Jardine The right shirt at the wrong time 135 Law & Order Jill Hennessy I didn’t know she could sing 143 Barry Manilow I right the wrongs, I right the wrongs 151 v Dancing in My Underwear A Bronx Tale Chazz Palminteri How lucky can one guy be? 159 Hall & Oates Daryl Hall The smile that lives forever 167 Wynonna Judd I’m smelling good for you and not her 173 The Beach Boys Jeffrey Foskett McGuinn and McGuire couldn’t get no higher . -

“Quiet Please, It's a Bloody Opera”!

UNIVERSITETET I OSLO “Quiet Please, it’s a bloody opera”! How is Tommy a part of the Opera History? Martin Nordahl Andersen [27.10.11] A theatre/performance/popular musicology master thesis on the rock opera Tommy by The Who ”Quiet please, it’s a bloody opera!” Martin Nordahl Andersen 2011 “Quiet please, it’s a bloody opera!” How is Tommy part of the Opera History? Print: Reprosentralen, University of Oslo All photos by Ross Halfin © All photos used with written permission. 1 ”Quiet please, it’s a bloody opera!” Aknowledgements I would like to thank my supervisors Ståle Wikshåland and Stan Hawkins for superb support and patience during the three years it took me to get my head around to finally finish this thesis. Thank you both for not giving up on me even when things were moving very slow. I am especially thankful for your support in my work in the combination of popular music/performance studies. A big thank you goes to Siren Leirvåg for guidance in the literature of theatre studies. Everybody at the Institute of Music at UiO for helping me when I came back after my student hiatus in 2007. I cannot over-exaggerate my gratitude towards Rob Lee, webmaster at www.thewho.com for helping me with finding important information on that site and his attempts at getting me an interview with one of the boys. The work being done on that site is fantastic. Also, a big thank you to my fellow Who fans. Discussing Who with you makes liking the band more fun. -

Elton John Page.Cdr

Elton John Music Titles Available from The Music Box, 30/31 The Lanes, Meadowhall Centre Sheffield S9 1EP Write with cheque made out to TMB Retail Music Ltd. or your card details or phone us on 0114 256 9089 Monday to Friday 10am- 8.45pm, Saturday 9am to 6.45pm or Sunday 11am to 4.30pm Elton John - Greatest Hits 1970-2002 IMP9807A £14.99 UK Postage £2.25 Your Song - Tiny Dancer - Honky Cat - Rocket Man (I Think It's Going To Be A Long, Long Time) - Crocodile Rock - Daniel - Saturday Night's Alright (For Fighting) - Goodbye Yellow Brick Road - Candle In The Wind - Bennie And The Jets - Don't Let The Sun Go Down On Me - The Bitch Is Back - Philadelphia Freedom - Someone Saved My Life Tonight - Island Girl - Don't Go Breaking My Heart - Sorry Seems To Be The Hardest Word - Blue Eyes - I'm Still Standing - I Guess That's Why They Call It The Blues - Sad Songs (Say So Much) - Nikita - Sacrifice - The One - Kiss The Bride - Can You Feel The Love Tonight - Circle Of Life - Believe - Made In England - Something About The Way You Look Tonight - Written In The Stars - I Want Love - This Train Don't Stop There Anymore - Song For Guy The Very Best Of Elton John BGP83627 £12.99 UK Postage £2.25 All the tracks from the definitive Elton John album of the same name for voice, piano and guitar chord boxes with full lyrics. Bennie And The Jets - Blue Eyes - Candle In The Wind - Crocodile Rock - Daniel - Don't Let The Sun Go Down On Me - Dont Go Breaking My Heart - Easier To Walk Away - Goodbye Yellow Brick Road - Honky Cat - I'm Still Standing - I Don't -

Mancave Games Virtual Pinball Game List

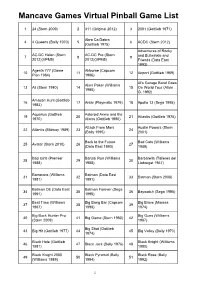

Mancave Games Virtual Pinball Game List 1 24 (Stern 2009) 2 311(Original 2012) 3 2001 (Gottlieb 1971) AbraCa Dabra 4 4Queens( Bally 1970) 5 6 ACDC (Stern 2012) (Gottlieb 1975) Adventures of Rocky AC-DC Helen( Stern AC-DC Pro (Stern 7 8 9 and Bullwinkle and 2012)(VPM5) 2012)(VPM5) Friends (DataEast 1993) Agents777 (Game Airborne (Capcom 10 11 12 Airport (Gottlieb 1969) Plan 1984) 1996) Al's Garage Band Goes Alien Poker (Williams 13 Ali (Stern 1980) 14 15 On World Tour (Alivin 1980) G. 1992) Amazon Hunt (Gottlieb 16 17 Antar (Playmatic 1979) 18 Apollo 13 (Sega 1995) 1983) Aquarius (Gottlieb Asteroid Annie andt he 19 20 21 Atlantis (Gottlieb 1975) 1970) Aliens (Gottlieb 1980) Attack From Mars Austin Powers (Stern 22 Atlantis (Midway 1989) 23 24 (Bally 1995) 2001) Back to the Future Bad Cats (Williams 25 Avatar (Stern 2010) 26 27 (DataEast 1990) 1989) Bad Girls (Premier Banzai Run (Williams Barbarella( Talleres del 28 29 30 1988) 1988) Llobregat 1967) Barracora (Williams Batman (DataEast 31 32 33 Batman (Stern 2008) 1981) 1991) Batman DE (DataEast Batman Forever (Sega 34 35 36 Baywatch (Sega 1995) 1991) 1995) Beat Time (Williams Big Bang Bar (Capcom Big Brave (Maresa 37 38 39 1967) 1996) 1974) Big Buck Hunter Pro Big Guns (Williams 40 41 Big Game (Stern 1980) 42 (Stern 2009) 1987) Big Shot (Gottlieb 43 Big Hit (Gottlieb 1977) 44 45 Big Valley (Bally 1970) 1974) Black Hole (Gottlieb Black Knight (Williams 46 47 Black Jack (Bally 1976) 48 1981) 1980) Black Knight 2000 Black Pyramid (Bally Black Rose (Bally 49 50 51 (Williams 1989) 1984) 1992) -

Brothers of Others Playlist

1. “In Your Eyes” 2. “She’s Too Good For Me” 3. “Tiny Dancer” 4. “Message In A Bottle” 5. “Don't Stop/Move By Yourself” 6. “Say” 7. “Apparently Nothing” 8. “You Are My Love” 9. “Everybody Wants To Rule” 10. “Hey Hey” 11. “Hide your love away” 12. “Hotel California” 13. “Drive” 14. “Last Dance With Mary Jane” 15. “Sex On Fire” Kings of Leon 16. “Stay” Rihanna 17. “Sail” Awolnation 18. “When I Was Your Man” Bruno Mars 19. “Dream on” Aerosmith 20. “Piece of my Heart” Janis Joplin 21. “Easy” The Commodores 22. “Georgia” Ray Charles 23. “Grapevine” Marvin Gaye 24. “Ain't Too Proud To Beg” The Temptations 25. “Creep” Radiohead 26. “Yellow” Coldplay 27. “Rocket Man” Elton John 28. “Your Song” Elton John 29. “Levon” Elton John 30. “Wonderwall” Oasis 31. “Something” Beatles 32. “Can't Always Get What You Want” Rolling Stones 33. “Sultans of Swing” Dire Straights 34. “Reeling in the Years” Steely Dan 35. “Wind Cries Mary” Jimi Hendrix 36. “Casey Jones” Grateful Dead 37. “I Will Wait” Mumford and Sons 38. “White Room” Cream 39. “Wonderful Tonight” Eric Clapton 40. “Money” Pink Floyd 41. “Hey Brother” Avicii 42. “People Get Ready” Impressions 43. “Blackbird” Beatles 44. “Let em in” Paul McCartney 45. “With a little help from my friends” Joe Cocker 46. “Wish You Were Here” Pink Floyd 47. “Take The Money And Run” Steve Miller Band 48. “The One I Love” REM 49. “Ramble On” Led Zeppelin 50. “Going to California” Led Zeppelin 51. “American Girl” Tom Petty 52. -

PINBALL NVRAM GAME LIST This List Was Created to Make It Easier for Customers to Figure out What Type of NVRAM They Need for Each Machine

PINBALL NVRAM GAME LIST This list was created to make it easier for customers to figure out what type of NVRAM they need for each machine. Please consult the product pages at www.pinitech.com for each type of NVRAM for further information on difficulty of installation, any jumper changes necessary on your board(s), a diagram showing location of the RAM being replaced & more. *NOTE: This list is meant as quick reference only. On Williams WPC and Sega/Stern Whitestar games you should check the RAM currently in your machine since either a 6264 or 62256 may have been used from the factory. On Williams System 11 games you should check that the chip at U25 is 24-pin (6116). See additional diagrams & notes at http://www.pinitech.com/products/cat_memory.php for assistance in locating the RAM on your board(s). PLUG-AND-PLAY (NO SOLDERING) Games below already have an IC socket installed on the boards from the factory and are as easy as removing the old RAM and installing the NVRAM (then resetting scores/settings per the manual). • BALLY 6803 → 6116 NVRAM • SEGA/STERN WHITESTAR → 6264 OR 62256 NVRAM (check IC at U212, see website) • DATA EAST → 6264 NVRAM (except Laser War) • CLASSIC BALLY → 5101 NVRAM • CLASSIC STERN → 5101 NVRAM (later Stern MPU-200 games use MPU-200 NVRAM) • ZACCARIA GENERATION 1 → 5101 NVRAM **NOT** PLUG-AND-PLAY (SOLDERING REQUIRED) The games below did not have an IC socket installed on the boards. This means the existing RAM needs to be removed from the board & an IC socket installed. -

QUINCY SYMPHONY CHORUS PROGRAM NOTES British Invasion ~ March 9, 2019 Dr

QUINCY SYMPHONY CHORUS PROGRAM NOTES British Invasion ~ March 9, 2019 Dr. Carol Mathieson Andrew Lloyd Webber relaunched musical theatre in the 1960’s in ways that welcomed electronic technology and rock music without allowing ephemeral fads to highjack well-crafted composition. And audiences responded, with younger aficionados swelling the general flock to the theatres. Tonight’s medley follows chronologically from earliest efforts with Tim Rice to turn Jesus Christ, Superstar— a scripture story recast in rock, produced as a concept album with basic plot, all the songs, and minimal dialog—into a stage show, opening in London’s West End. It was a mega-hit. Soon after came Evita about the Perón dictatorship in Argentina. Rice did not feel comfortable remolding established writing into lyrics, so for Cats, Lloyd Webber went directly to T.S. Eliot’s poetry. Song and Dance is a short musical play with lyrics by Don Black, paired with a short ballet with music Lloyd Webber wrote for his cellist brother Julien as variations on a Paganini caprice. However, Phantom of the Opera, with Charles Hart lyrics, was back to high drama. Phantom smashed attendance records in both London and New York, running for decades. Tonight’s medley opens and closes with songs from that iconic show. Nineteenth-century English musical theatre consisted of cheerful song and dance revues or badly translated, risqué French burlesques until Gilbert and Sullivan brought satirical, silly Savoy Operas to a family-friendly stage. QSC sings highlights from the first and the final masterpieces of these saviors of both the English and American musical stage. -

Gottlieb Run Outrages Lancman

LocaL cLassifieds inside April 15, 2012 Your Neighborhood — Your News® Renaissance Gottlieb run outrages Lancman turns LIC into Accusations fly among Democrats as fourth enters congressional race prime location seeking a spot in the Democratic And then the finger pointing Gottlieb, who he called a “long- By Joe ANutA primary for a Queens congres- began. time party hack,” as a sham can- By ReBecca HeNely sional seat, state Assemblyman Lancman accused the didate. After word spread that Jeff Rory Lancman (D-Fresh Mead- Queens County Democrats and “Today, the Meng campaign The opening of JetBlue’s new Gottlieb, a 70-year-old employee of ows) said it was a ploy to siphon state Assemblywoman Grace has been caught red-handed in office and a new park in Long Is- the state Board of Elections, was votes away from him. Meng’s campaign of propping up one of the most malicious schemes land City last week was hailed as any of us have ever seen: an outra- a milestone for the community by geous ploy to deceive Jewish vot- leaders around the city, but the Pl a y Ba l l ! ers with a fraudulent candidate neighborhood has been growing designed to manipulate the elec- and changing for some time. toral process in her favor,” said After years of being known Lancman’s campaign manager, as a manufacturing mecca, Long Mark Benoit. Island City has become one of Lancman contends that Jew- Queens’ most up-and-coming ish voters will pull the lever for communities. Gottlieb just be- Its million-dollar views of cause of his Jew- Manhattan ish last name, have attract- Full coverage taking away ed residential votes the assem- development, PAGES 18,19 blyman believes would otherwise the hotel in- go to him.