UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Le Rôle Du Gouvernement De Vichy Dans La Rafle Du Vel' D'hiv' Et Sa Mémoire Aux Yeux De La

The College of Wooster Libraries Open Works Senior Independent Study Theses 2016 La Trahison et la honte : Le rôle du gouvernement de Vichy dans la rafle du elV ’ d’Hiv’ et sa mémoire aux yeux de la société française Olivia Bolek College of Wooster, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://openworks.wooster.edu/independentstudy Part of the Other French and Francophone Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Bolek, Olivia, "La Trahison et la honte : Le rôle du gouvernement de Vichy dans la rafle du eV l’ d’Hiv’ et sa mémoire aux yeux de la société française" (2016). Senior Independent Study Theses. Paper 6979. https://openworks.wooster.edu/independentstudy/6979 This Senior Independent Study Thesis Exemplar is brought to you by Open Works, a service of The oC llege of Wooster Libraries. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Independent Study Theses by an authorized administrator of Open Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. © Copyright 2016 Olivia Bolek Abstract While many people know that World War II France was occupied by the Germans, retaining little sovereignty in the de facto Vichy government, many may not realize the extent to which the French collaborated with their Nazi occupiers and how many anti-Semitic measures were in fact created by the Vichy government. After the war, the crimes committed by the French against the Jews became a taboo which slowly transformed over the years into what is today considered to be an obsession with the topic. These events are best demonstrated through the 1942 Vel’ d’Hiv’ roundup in which Parisian authorities gathered over 13,000 Jews, detaining over half of them in the Vélodrome d’Hiver, an indoor cycling arena in Paris, for almost a week without food, water, or sanitation. -

Vichy France and the Jews

VICHY FRANCE AND THE JEWS MICHAEL R. MARRUS AND ROBERT 0. PAXTON Originally published as Vichy et les juifs by Calmann-Levy 1981 Basic Books, Inc., Publishers New York Contents Introduction Chapter 1 / First Steps Chapter 2 / The Roots o f Vichy Antisemitism Traditional Images of the Jews 27 Second Wave: The Crises of the 1930s and the Revival of Antisemitism 34 The Reach of Antisemitism: How Influential Was It? 45 The Administrative Response 54 The Refugee Crisis, 1938-41 58 Chapter 3 / The Strategy o f Xavier Vallat, i 9 4 !-4 2 The Beginnings of German Pressure 77 Vichy Defines the Jewish Issue, 1941 83 Vallat: An Activist at Work 96 The Emigration Deadlock 112 Vallat’s Fall 115 Chapter 4 / The System at Work, 1040-42 The CGQJ and Other State Agencies: Rivalries and Border Disputes 128 Business as Usual 144 Aryanization 152 Emigration 161 The Camps 165 Chapter 5 / Public Opinion, 1040-42 The Climax of Popular Antisemitism 181 The DistriBution of Popular Antisemitism 186 A Special Case: Algeria 191 The Churches and the Jews 197 X C ontents The Opposition 203 An Indifferent Majority 209 Chapter 6 / The Turning Point: Summer 1Q42 215 New Men, New Measures 218 The Final Solution 220 Laval and the Final Solution 228 The Effort to Segregate: The Jewish Star 234 Preparing the Deportation 241 The Vel d’Hiv Roundup 250 Drancy 252 Roundups in the Unoccupied Zone 255 The Massacre of the Innocents 263 The Turn in PuBlic Opinion 270 Chapter 7 / The Darquier Period, 1942-44 281 Darquier’s CGQJ and Its Place in the Regime 286 Darquier’s CGQJ in Action 294 Total Occupation and the Resumption of Deportations 302 Vichy, the ABBé Catry, and the Massada Zionists 310 The Italian Interlude 315 Denaturalization, August 1943: Laval’s Refusal 321 Last Days 329 Chapter 8 / Conclusions: The Holocaust in France . -

Report to the Public on the Work of the 2019 Proceedings of the Symposium Held on November 15, 2019

Commission pour l’indemnisation des victimes de spoliations intervenues du fait des législations antisémites en vigueur pendant l’Occupation Report to the public on the work of the 2019 Proceedings of the symposium held on November 15, 2019 Speech by French President Jacques Chirac, on July 16, 1995, at the commemoration of the Vel’ d’Hiv’ roundup (July 16, 1942) Excerpts « In the life of a nation, there are times that leave painful memories and damage people’s conception of their country. It is difficult to evoke these moments because we can never find the proper words to describe their horror or to express the grief of those who experienced their tragedy. They will carry forever, in their souls and in their flesh, the memory of these days of tears and shame. [… ] On that day, France, land of the Enlightenment, of Human Rights, of welcome and asylum, committed the irreparable. Breaking its word, it handed those who were under its protection over to their executioners. [… ] Our debt to them is inalienable. [… ] In passing on the history of the Jewish people, of its sufferings and of the camps. In bearing witness again and again. In recognizing the errors of the past, and the errors committed by the State. In concealing nothing about the dark hours of our history, we are simply standing up for a vision of humanity, of human liberty and dignity. We are thus struggling against the forces of darkness, which are constantly at work. [… ] Let us learn the lessons of history. Let us refuse to be passive onlookers, or accomplices, of unacceptable acts. -

Jean Cocteau's the Typewriter

1 A Queer Premiere: Jean Cocteau’s The Typewriter Introduction Late in April 1941, toward the close of the first Parisian theatre season fol- lowing the Defeat, Jean Cocteau’s La Machine à écrire (The Typewriter) opened, then closed, then reopened at the Théâtre Hébertot. Written in the style of a detective drama, the play starred the actor generally known—at least in the entertainment world at the time—as Cocteau’s sometime lover and perpetual companion, Jean Marais, as identical twin brothers. The re- views are curiously reticent about what exactly occurred at the Hébertot, and historians and critics offer sometimes contradictory pieces of a puzzle that, even when carefully put together, forms an incomplete picture. The fragments are, however, intriguing. Merrill Rosenberg describes how, on the evening of April 29, 1941, the dress rehearsal (répétition génerale), sponsored “as a gala” by the daily Paris-Soir and attended by various “dig- nitaries,” caused in the Hébertot’s auditorium a demonstration by members of the Parti Populaire Français (PPF). This disruption prompted Vichy’s ambas- sador to Paris, Fernand de Brinon, to order the withdrawal of the production (“Vichy’s Theatrical Venture” 136). Francis Steegmuller describes the disor- der that greeted the Typewriter premiere and the revival of Les Parents Terribles (at the Gymnase later that year): “stink bombs exploded in the theatres, and hoodlums filled the aisles and climbed onto the stage, shouting obscenities at Cocteau and Marais as a couple” (442).1 Patrick Marsh too notes that these plays “were seriously disrupted by violent scenes fomented by fascist sym- pathizers and members of the Parti Populaire Français” (“Le Théâtre 1 2 THE DRAMA OF FALLEN FRANCE Français . -

Collaboration in Europe, 1939-1945

Occupy/Be occupied Collaboration in Europe, 1939-1945 Barbara LAMBAUER ABSTRACT Collaboration in wartime not only concerns relations between the occupiers and occupied populations but also the assistance given by any government to a criminal regime. During the Second World War, the collaboration of governments and citizens was a crucial factor in the maintenance of German dominance in continental Europe. It was, moreover, precisely this assistance that allowed for the absolutely unprecedented dimensions of the Holocaust, a crime perpetrated on a European scale. Pétain meeting Hitler at Montoire on 24 October 1940. From the left: Henry Philippe Pétain, Paul-Otto Schmidt, Adolf Hitler, Joachim v. Ribbentrop. Photo : Heinrich Hoffman. The occupation of a territory is a common feature of war and brings with it acts of both collaboration and resistance. The development of national consciousness from the end of the 18th century and the growing identification of citizens with the state changed the way such behaviour was viewed, a moral judgement being attributed to loyalty to the state, and to treason against it. During the Second World War, and in connection with the crimes committed by Nazi Germany, the term “collaboration” acquired the particularly negative connotations that it has today. It cannot be denied that collaboration by governments as well as by individual citizens was a fundamental element in the functioning of German-occupied Europe. Moreover, unlike the explicit ideological engagement of some Europeans in the Nazi cause, it was by no means a marginal phenomenon. Nor was it limited only to countries occupied by the Wehrmacht: the governments of independent countries such as Finland, Hungary, Romania or Bulgaria collaborated, as did those of neutral countries such as Switzerland, Sweden and Portugal, albeit to varying degrees. -

Retrospective Is Curated by Toby Kamps with Dr

Wols: Retrospective is curated by Toby Kamps with Dr. Ewald Rathke. This exhibition is generously supported by the National Endowment for the Arts; Anne and Bill Stewart; Louisa Stude Sarofim; Michael Born Alfred Otto Wolfgang Schulze to a prominent Berlin family Zilkha; Skadden, Arps; and the City of Houston. on May 27, 1913, the artist spent his childhood in Dresden. Despite obvious intelligence, Wols failed to complete school, and in 1932, not long after the death of his father, with whom he had a contentious relationship, he moved to Paris in an attempt to break away from his bourgeois roots. Except for a brief stint in Spain, he remained in France until his untimely death in 1951. The story of Wols’s dramatic trans- PUBLIC PROGRAMS formation from sensitive, musically gifted German youth to eccentric, Panel Discussion near-homeless Parisian artist is legendary. So too are accounts of his Thursday, September 12, 2013, 6:00 p.m. many adventures and misadventures during the tumult of wartime Following introductory remarks by Frankfurt-based scholar Dr. Ewald Europe: his marriage to the fiercely protective Romanian hat maker Rathke, Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art Toby Kamps is joined Gréty Dabija; his grueling incarceration as an expatriate at the outset by art historians Patrycja de Bieberstein Ilgner, Archivist at the Karin and of the war and subsequent moves across rural France; his late-night Uwe Hollweg Foundation, Bremen, Germany; and Katy Siegel, Professor perambulations in liberated Paris; and his ever-worsening alcoholism, of Art History at Hunter College, New York, and Chief Curator of the Wols, Selbstporträt (Self-Portrait), 1937 or 1938, modern print. -

Max Klinger (1857 Leipzig – 1920 Großjena, Sachsen-Anhalt) Venus Im Muschelwagen, Um 1912 Öl Auf Leinwand 56 X 233 Cm Rechts Unten Monogrammiert: “MK”

Max Klinger (1857 Leipzig – 1920 Großjena, Sachsen-Anhalt) Venus im Muschelwagen, um 1912 Öl auf Leinwand 56 x 233 cm Rechts unten monogrammiert: “MK” Provenienz: − Paul von Bleichert, Leipzig − Auktionshaus Hugo Helbing, München, 23. April 1929, Los 41 (betitelt „Meeresgötter“) − Wilhelm Hartmann, Berlin − Galerie Franz Brutscher, München − Kurt Liebermeister, München − Privatsammlung Ausstellungen: − Grosse Kunstausstellung Dresden 1912 − Secession. Europäische Kunst um die Jahrhundertwende, Haus der Kunst, München 1964, Kat. Nr. 269 Superstar des Symbolismus Bahnbrechende Erkenntnisse auf sämtlichen Gebieten der Wissenschaft prägen die letzten Jahrzehnte des 19. Jahrhun- derts und verändern die Lebensrealität der Menschen radikal. In der Folge kommt es zu einer noch nie dagewesenen Vielfalt an künstlerischen Strömungen, wobei sich der Symbolismus als eine der wichtigsten herauskristallisiert. In Max Klinger findet er einen seiner prominentesten Protagonisten. Wie kaum ein anderer Künstler des Fin de Siècle versteht es der aus Leipzig stammende Grafiker, Zeichner, Maler und Bildhauer das Be- dürfnis seiner Zeitgenossen zu befriedigen, dem profanen Alltag durch das Eintauchen in geheimnisvolle Bildwelten zu entfliehen. Dies trägt ihm kultische Verehrung ein und macht ihn zu einem wesentlichen Impulsgeber der frühen Moderne. Max Klinger Foto von Nicola Perscheid, um 1900 Auf zu neuen Ufern Zu den Schlüsselwerken der Epoche zählt das von Max Klinger zu Beginn der 1880er Jahre gestaltete Bildprogramm für das Vestibül der Villa Albers in Berlin. Das als erstes Gesamtkunstwerk auf deut- schem Boden geltende Ensemble wurde bereits wenige Jahre nach seiner Entstehung von den Erben des Auftraggebers an die Berliner Nationalgalerie, die Hamburger Kunsthalle sowie das Museum der Bildenden Künste in Leipzig verkauft. Eines der zentralen Gemälde des Zyklus ist die Venus im Muschelwagen. -

Press Release

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE WOLS Vintage Photographs from the 1930s February 22 – April 21, 2001 Ubu Gallery is pleased to present Wols: Vintage Photographs from the 1930s. Vintage photographs by Wols are extremely rare and the exhibition at Ubu will contain approximately 30 images covering the four principal areas of Wols’s photographic output –still lifes, portraits, fashion and abstraction. Wols’s photographs are known largely through modern prints made from original negatives, which were exhibited at the Von der Heydt-Museum in Wuppertal and the Kestner-Gesellschaft in Hannover (both in 1978) and at the Kunsthaus Zürich in 1996. Both vintage and modern prints were exhibited at the Busch-Reisinger Museum (Harvard University) in 1999. A set of modern prints is also in the collection of The J. Paul Getty Museum. Wols (the pseudonym of Alfred Otto Wolfgang Schulze, b. Germany 1913, d. France 1951) occupies a mythic position in post-war European painting as an emblematic figure of the Informel movement, which like its American counterpart “Abstract Expressionism,” was a bridge between Surrealist-inspired automatism and gestural abstraction. When Wols arrived in Paris in 1932, he was already practicing photography. It is the influence of the two prevailing, yet seemingly antithetical, photographic currents of the times –Surrealism in France and Neue Sachlichkeit (“New Objectivity”) in Germany– that imbues his photographic oeuvre with its unique and distinctive vision. In Paris, Wols made the acquaintance of Fernand Léger and Amédée Ozenfant through the introduction of the Bauhaus master, László Moholy-Nagy. Wols had met Moholy-Nagy having gone to Berlin to attend the Bauhaus –recently closed– on the recommendation of the Dresden-based photographer, Hugo Erfurth. -

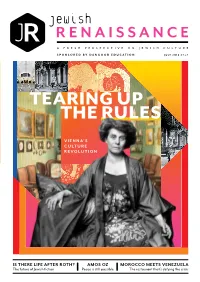

Tearing up the Rules

Jewish RENAISSANCE A FRESH PERSPECTIVE ON JEWISH CULTURE SPONSORED BY DANGOOR EDUCATION JULY 2018 £7.25 TEARING UP THE RULES VIENNA’S CULTURE REVOLUTION IS THERE LIFE AFTER ROTH? AMOS OZ MOROCCO MEETS VENEZUELA The future of Jewish fiction Peace is still possible The restaurant that’s defying the crisis JR Pass on your love of Jewish culture for future generations Make a legacy to Jewish Renaissance ADD A LEGACY TO JR TO YOUR WILL WITH THIS SIMPLE FORM WWW.JEWISHRENAISSANCE.ORG.UK/CODICIL GO TO: WWW.JEWISHRENAISSANCE.ORG.UK/DONATIONS FOR INFORMATION ON ALL WAYS TO SUPPORT JR CHARITY NUMBER 1152871 JULY 2018 CONTENTS WWW.JEWISHRENAISSANCE.ORG.UK JR YOUR SAY… Reader’s rants, raves 4 and views on the April issue of JR. WHAT’S NEW We announce the 6 winner of JR’s new arts award; Mike Witcombe asks: is there life after Roth? FEATURE Amos Oz on Israel at 10 70, the future of peace, and Trump’s controversial embassy move. FEATURE An art installation in 12 French Alsace is breathing new life into an old synagogue. NATALIA BRAND NATALIA © PASSPORT Vienna: The writers, 14 artists, musicians and thinkers who shaped modernism. Plus: we speak to the contemporary arts activists working in Vienna today. MUSIC Composer Na’ama Zisser tells Danielle Goldstein about her 30 CONTENTS opera, Mamzer Bastard. ART A new show explores the 1938 32 exhibition that brought the art the Nazis had banned to London. FILM Masha Shpolberg meets 14 34 the director of a 1968 film, which followed a group of Polish exiles as they found haven on a boat in Copenhagen. -

Birth of Modernism

EN OPENING MARCH 16TH BIRTH OF (Details) Wien Museum, © Leopold Werke: Moriz Nähr ÖNB/Wien, Klimt, Weitere Gustav Pf 31931 D (2). MODERNISM PRESS RELEASE VIENNA 1900 BIRTH OF MODERNISM FROM 16TH MARCH 2019 The exhibition Vienna 1900. Birth of Modernism has been conceived as the Leopold Muse- um’s new permanent presentation. It affords insights into the enormous wealth and diver- sity of this era’s artistic and intellectual achievements with all their cultural, social, political and scientific implications. Based on the collection of the Leopold Museum compiled by Ru- dolf Leopold and complemented by select loans from more than 50 private and institutional collections, the exhibition conveys the atmosphere of the former metropolis Vienna in a unique manner and highlights the sense of departure characterized by contrasts prevalent at the turn of the century. The presentation spans three floors and features some 1,300 exhibits over more than 3,000 m2 of exhibition space, presenting a singular variety of media ranging from painting, graphic art, sculpture and photography, via glass, ceramics, metals, GUSTAV KLIMT textiles, leather and jewelry, all the way to items of furniture and entire furnishings of apart- Death and Life, 1910/11, reworked in 1915/16 ments. The exhibition, whose thematic emphases are complemented by a great number of Leopold Museum, Vienna archival materials, spans the period of around 1870 to 1930. Photo: Leopold Museum, Vienna/ Manfred Thumberger UPHEAVAL AND DEPARTURE IN VIBRANT FIN-DE-SIÈCLE VIENNA At the turn of the century, Vienna was the breeding ground for an unprecedentedly fruitful intellectual life in the areas of arts and sciences. -

Als PDF Herunterladen

Bevor es richtig losging, war eigentlich alles schon vorbei. „… während man denkt, das wären alles nur Vorbereitungen zum Photographiertwerden, bist du schon längst konterfeit. X-mal hat sie geknipst und du hast es nicht gemerkt.“ In ihrer Biografie „Mein Leben mit Alfred Loos“ beschreibt die Wiener Schauspielerin Elsie Altmann-Loos in einem kurzen Kapitel einen Termin im Atelier der Fotografien Dora Kallmus, die sich als d’Ora im Wien des beginnenden 20. Jahrhunderts rasch einen Namen machte. Die Liste der Klientinnen und Klienten der aus bürgerlichem Hause stammenden frühen Karrierefrau (ihr Vater war der jüdische Hof- und Gerichtsadvokat Dr. Philipp Kallmus) liest sich wie ein Who is Who der Wiener High Society. Vom Adelsgeschlecht der Habsburger über literarische Größen wie Arthur Schnitzler und Karl Kraus bis hin zu bekannten Künstlern wie Gustav Klimt und Tänzerinnen wie Anita Berber – kaum jemand, der hierzulande in die Annalen der Geschichte einging, der nicht zumindest ein Mal vor die Kameralinse der Dora Kallmus getreten wäre. Wer schön sein wollte ging zu Madame d’Ora. Das belegt auch ein Brief von Alma Mahler Werfel, in dem es um eine auszuführende Retusche ging. Die talentierte Fotografin war nicht nur ehrgeizig und in technischen Belangen versiert. Neben neuesten Portraittechniken, die sie sich unter anderen im Rahmen eines Praktikums im damals wegweisenden Studio von Nicola Perscheid in Berlin aneignete, wurde ihr zudem ein gutes Maß an Intuition bekundet. Aber auch ihr Geschick, wenn es darum ging, das passende Ambiente zu erzeugen, kam ihr zugute. Bereits ihr Wiener Atelier, im Stile der Wiener Werkstätten eingerichtet, zeugte vom guten Geschmack. -

History of a Natural History: Max Ernst's Histoire Naturelle

HISTORY OF A NATURAL HISTORY: MAX ERNST'S HISTOIRE NATURELLE, FROTTAGE, AND SURREALIST AUTOMATISM by TOBIAS PERCIVAL ZUR LOYE A THESIS Presented to the Department of Art History and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts June 2010 --------------_._--- 11 "History of a Natural History: Max Ernst's Histoire Naturelle, Frottage, and Surrealist Automatism," a thesis prepared by Tobias Percival zur Loye in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts degree in the Department of Art History. This thesis has been approved and accepted by: Date Committee in Charge: Dr. Sherwin Simmons, Chair Dr. Joyce Cheng .Dr. Charles Lachman Accepted by: Dean of the Graduate School III An Abstract of the Thesis of Tobias Percival zur Loye for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Art History to be taken June 2010 Title: HISTORY OF A NATURAL HISTORY: MAX ERNST'S HISTOIRE NATURELLE, FROTTAGE, AND SURREALIST AUTOMATISM Approved: When Andre BreJon released his Manifesto ofSurrealism in 1924, he established the pursuit of psychic automatism as Surrealism's principle objective, and a debate concerning the legitimacy or possibility of Surrealist visual art ensued. In response to this skepticism, Max Ernst embraced automatism and developed a new technique, which he called frottage , in an attempt to satisfy Breton's call for automatic activity, and in 1926, a collection of thirty-four frottages was published under the title Histoire Naturelle. This thesis provides a comprehensive analysis of Histoire Naturelle by situating it in the theoretical context of Surrealist automatism and addresses the means by which Ernst incorporated found objects from the natural world into the semi-automatic production of his frottages.