Strangers on a Commuter Train

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Japan's Powder Paradise

tokyo FEBRUARY 2012 weekenderJapan’s premier English language magazine Since 1970 HOKKAIDO JAPAN’S POWDER PARADISE LOVE IS IN THE AIR TWELVE DATE TIPS FOR 2012 VALENTINE’S RESTAURANT GUIDE EDUCATION SPECIAL CAN JAPAN EMBRACE THE 4 F’S? A PIONEERING INTERNATIONAL SCHOOL AGENDA INTERVIEW PLUS! All The Biggest Live Weekender Q&A with WIN Great Prizes with Shows this Month German Ambassador our Readers Survey IN THIS ISSUE: The Latest APAC news from the Asia Daily Wire, People Parties & Places, Hit the Ice in Tokyo and much more... FEBRUARY, 2012 CONTENTS ON PISTE IN HOKKAIDO Weekender heads north to Hokkaido’s winter wonderland. VALENTINE’S DAY PEOPLE, PARTIES, PLACES AGENDA Twelve date ideas for 2012 and Tokyo’s longest running society columnist The best live shows coming up a gorgeous Grand Marnier recipe. hangs out with the Jacksons. in Tokyo this month. 11 Asia Daily Wire 22 Hoshino Resort Tomamu 36 American Apparel A roundup of all the top APAC news of the Exploring one of Hokkaido’s most After a great 2011, the LA based fashion past month. luxurious ski resorts. basics brand is expanding in Japan. 12 German Ambassador Interview 31 Education Special 38 Bill Hersey Q&A with Volker Stanzel, Ambassador of Weekender asks, can Japan embrace the Tokyo’s Longest Running Society Column the Federal Republic of Germany. 4 F’s instead of the 3 R’s? Printed in Weekender For 42 Years! 16 Tokyo Restaurant Guide 32 ISAK 43 Win a Skincare Set Worth ¥30,000 Special guide to Tokyo’s top restaurants An international school with a difference. -

THE WESTIN TOKYO Sakura Map

THE WESTIN TOKYO Sakura Map 1 Meguro River 2 Yoyogi Park Take the JR Yamanote Line from Ebisu Station to Take the JR Yamanote Line from Ebisu Station to Meguro Station (3 minutes). 5 minutes' walk from Harajuku Station (5 minutes). 3 minutes' walk from Meguro Station. Harajuku Station. Along both sides of the river banks spanning Atop the vast lawn, you will find cherry trees 4km, you will find 800 Somei Yoshino cherries in full bloom. This is a popular cherry in bloom. At night, they are illuminated. blossom viewing location. Ueno 4 Yamanote Line Sobu Line Kudanshita Hanzomon Line 7 Shinjyuk3ugyoen 3 Shinjyuku Gyoen National Park 4 Ueno Onshi Park Take the JR Yamanote Line from Ebisu Station to Shinjuku Take the JR Yamanote Line from Ebisu Station to Shinjyuku Station. From Shinjuku Station, board the Tokyo Metro Ueno Station (30 minutes). 2 minutes' walk from the Marunouchi Line and take it to Shinjuku-gyoenmae Station (3 Ueno Park exit of Ueno Station. minutes). 5 minutes' walk from Shinjuku-gyoenmae Station. The main road through the park features Enjoy 1,300 cherry trees of 65 varieties 1,200 cherry trees, making it one of the Marunouchi Line 6 outbloom. foremost destinations in Tokyo. Roppongi 5 Tokyo Midtown Harajyuku Shinanomachi 2 Take the Tokyo Metro Hibiya Line from Ebisu Station to Roppongi Station (6 minutes). 6 minutes' walk from Roppongi Station. 5 When in full bloom, sakura street is turned to sakura tunnel. At night, their illuminated blossoms create a bewitching mood. Hibiya Line 8 6 Meiji Jingu Gaien Ebisu Hamamatsucho Take the JR Yamanote Line from Ebisu Station to Yoyogi Station (8 minutes). -

The JR Pass: 2 Weeks in Japan

Index Introduction to Travel in Japan………………………………… 1 - 7 Day 1 | Sakura Blooms in North Japan…………………….. 8 - 12 Day 2 |Culture in Kyoto…………………………………………… 13 - 18 Day 3 | Shrines and Bamboo Forests……………………….. 19 - 24 Day 4 | The Alpine Route………………………………………… 25 - 29 Day 5 | Takayama Mountain Village……………………….. 30 - 34 Day 6 | Tokyo by Day, Sendai at Night…………………….. 35 - 40 Day 7 | Exploring Osaka………………………………………….. 41 - 44 Day 8 | The 8 Hells of Beppu…………………………………… 45 - 50 Day 9 | Kawachi Fuji Gardens………………………………….. 51 - 53 Day 10 | Tokyo Indulgence………………………………………. 54 - 58 Day 11 | The Ryokan Experience at Mount Fuji……….. 59 - 64 Day 12 | The Fuji Shibazakura Festival……………………… 65 - 70 Day 13 | Harajuku and Shinjuku (Tokyo)…………………… 71 - 75 Day 14 | Sayonara!........................................................ 76 - 78 The Final Bill ……………………………………………………………. 79 1 We Owned the JR Pass: 2 Weeks in Japan May 29, 2015 | By Allan and Fanfan Wilson of Live Less Ordinary Cities can be hard to set apart when rattling past the backs of houses, on dimly lit train lines. Arriving to Tokyo it feels no different, and were it not for the alien neon lettering at junctions, we could have been in any city of the world. “It reminds me of China” Fanfan mutters at a time I was feeling the same. It is at this point where I realize just how little I know about Japan. My first impressions? It’s not as grainy as Akira Kurosawa movies, and nowhere near as animated as Manga or Studio Ghibli productions. This is how I know Japan; through movies and animation, with samurai and smiling eyes. I would soon go on to know and love Japan for many other reasons, expected and unexpected during our 2 week JR pass journeys. -

Unifying Rail Transportation and Disaster Resilience in Tokyo

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville ScholarWorks@UARK Architecture Undergraduate Honors Theses Architecture 5-2020 The Yamanote Loop: Unifying Rail Transportation and Disaster Resilience in Tokyo Mackenzie Wade Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uark.edu/archuht Part of the Urban, Community and Regional Planning Commons Citation Wade, M. (2020). The Yamanote Loop: Unifying Rail Transportation and Disaster Resilience in Tokyo. Architecture Undergraduate Honors Theses Retrieved from https://scholarworks.uark.edu/archuht/41 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Architecture at ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Architecture Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Yamanote Loop: Unifying Rail Transportation and Disaster Resilience in Tokyo by Mackenzie T. Wade A capstone submitted to the University of Arkansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Honors Program of the Department of Architecture in the Fay Jones School of Architecture + Design Department of Architecture Fay Jones School of Architecture + Design University of Arkansas May 2020 Capstone Committee: Dr. Noah Billig, Department of Landscape Architecture Dr. Kim Sexton, Department of Architecture Jim Coffman, Department of Landscape Architecture © 2020 by Mackenzie Wade All rights reserved. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to acknowledge my honors committee, Dr. Noah Billig, Dr. Kim Sexton, and Professor Jim Coffman for both their interest and incredible guidance throughout this project. This capstone is dedicated to my family, Grammy, Mom, Dad, Kathy, Alyx, and Sam, for their unwavering love and support, and to my beloved grandfather, who is dearly missed. -

Shinjuku Rules of Play

Shinjuku Rules of Play Gary Kacmarcik Version 2 r8 Tokyo is a city of trains and Shinjuku is the busiest In Shinjuku, you manage one of these con- train station in the world. glomerates. You need to build Stores for the Customers to visit while also constructing the rail Unlike most passenger rail systems, Tokyo has lines to get them there. dozens of companies that run competing rail lines rather than having a single entity that manages rail Every turn, new Customers arrive looking to for the entire city. Many of these companies are purchase a specific good. If you have a path to a large conglomerates that own not only the rail, but Store that sells the goods they want, then you also the major Department Stores at the rail might be able to move those new Customers to stations. your Store and work toward acquiring the most diverse collection of Customers. Shinjuku station (in Shinjuku Ward) expands down into Yoyogi station in Shibuya Ward. A direct rail connection exists between these 2 stations that can be used by any player. Only Stores opened in stations with this Sakura icon may be upgraded to a Department Store. Department Store Upgrade Bonus tokens are placed here. The numbers indicate the total number of customers in the Queue (initially: 2). Customer Queue New Customers will arrive on the map from here. Stations are connected by lines showing potential Components future connections. These lines cannot be used until a player uses theE XPAND action to place track Summary on them, turning them into a rail connection. -

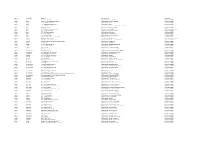

Area Locality Address Description Operator Aichi Aisai 10-1

Area Locality Address Description Operator Aichi Aisai 10-1,Kitaishikicho McDonald's Saya Ustore MobilepointBB Aichi Aisai 2283-60,Syobatachobensaiten McDonald's Syobata PIAGO MobilepointBB Aichi Ama 2-158,Nishiki,Kaniecho McDonald's Kanie MobilepointBB Aichi Ama 26-1,Nagamaki,Oharucho McDonald's Oharu MobilepointBB Aichi Anjo 1-18-2 Mikawaanjocho Tokaido Shinkansen Mikawa-Anjo Station NTT Communications Aichi Anjo 16-5 Fukamachi McDonald's FukamaPIAGO MobilepointBB Aichi Anjo 2-1-6 Mikawaanjohommachi Mikawa Anjo City Hotel NTT Communications Aichi Anjo 3-1-8 Sumiyoshicho McDonald's Anjiyoitoyokado MobilepointBB Aichi Anjo 3-5-22 Sumiyoshicho McDonald's Anjoandei MobilepointBB Aichi Anjo 36-2 Sakuraicho McDonald's Anjosakurai MobilepointBB Aichi Anjo 6-8 Hamatomicho McDonald's Anjokoronaworld MobilepointBB Aichi Anjo Yokoyamachiyohama Tekami62 McDonald's Anjo MobilepointBB Aichi Chiryu 128 Naka Nakamachi Chiryu Saintpia Hotel NTT Communications Aichi Chiryu 18-1,Nagashinochooyama McDonald's Chiryu Gyararie APITA MobilepointBB Aichi Chiryu Kamishigehara Higashi Hatsuchiyo 33-1 McDonald's 155Chiryu MobilepointBB Aichi Chita 1-1 Ichoden McDonald's Higashiura MobilepointBB Aichi Chita 1-1711 Shimizugaoka McDonald's Chitashimizugaoka MobilepointBB Aichi Chita 1-3 Aguiazaekimae McDonald's Agui MobilepointBB Aichi Chita 24-1 Tasaki McDonald's Taketoyo PIAGO MobilepointBB Aichi Chita 67?8,Ogawa,Higashiuracho McDonald's Higashiura JUSCO MobilepointBB Aichi Gamagoori 1-3,Kashimacho McDonald's Gamagoori CAINZ HOME MobilepointBB Aichi Gamagori 1-1,Yuihama,Takenoyacho -

The Ultimate Guide to Summer Travel in Japan

Ultimate Guide to Summer Travelling in Japan Ver.1.1 May 2016 The Ultimate Guide to Summer Travel in Japan By ©Live! Work! Play! JAPAN! © Live! Work! Play! JAPAN! Page 1/24 Ultimate Guide to Summer Travelling in Japan Ver.1.1 May 2016 So you are going to Japan for summer vacation! Maybe it's your first time here or maybe you live in Japan and have a nice long break to spend travelling around. For those of you planning your first holiday in Japan, I can imagine how anxious you must be. It isn’t the biggest country in the world, yet there is so much to see and do! We don't want you to waste your time here, so we have prepared what we think is a great itinerary for Japan, giving you opportunities to see everything, and maybe a bit of time to have some serendipitous adventuring too! Some of the places in this guide are obvious, and some you can only appreciate if you have been to Japan. If you have any suggestions, you can tell us at the bottom of the post on our website or on the Facebook page; we always listen to feedback and if you know somewhere awesome to go, don't hesitate to share. © Live! Work! Play! JAPAN! Page 2/24 Ultimate Guide to Summer Travelling in Japan Ver.1.1 May 2016 Itinerary Contents Day 1: Arrive in Tokyo 東京, then REST. Day 2: What you Must See in Tokyo. 浅草神社 Asakusa Shrine. 渋谷スクランブル Shibuya Crossing. 東京スカイツリー Tokyo Skytree OR 東京都庁 Tokyo Metropolitan Building. -

Day 1, Tuesday July 05, 2016

Tokyo for Jeff and Lauren Day 1, Tuesday July 05, 2016 1: Rest Up at the Aman Tokyo (Lodging) Address: Japan, 〒100-0004 Tokyo, Chiyoda, 大手町1-5-6 About: The hotel: Set in top 6 floors of a sleek, modern high-rise, this luxury hotel is an 8-minute walk from the bustling Tokyo Station, and 3 km from the landmark Tsukiji Market With floor-to-ceiling windows and sweeping city views, the elegant rooms, decorated in stone, wood and paper screens, feature free Wi-Fi, flat-screen TVs, deep soaking tubs and minibars. Suites add living rooms and wine cellars The spa: Drawing on traditional natural remedies and the principles of balancing mind and body, Aman Spa offers an integrated approach to wellbeing. Several Spa treatment rooms are complemented by large Japanese-style hot baths and steam rooms, a 30-metre heated pool with city views, a fitness centre equipped with the latest cardiovascular and weight training machinery, as well as a dedicated yoga and Pilates studio. Their minute seasonal journey starts off with a foot bath comprised of hot water, sake koji paste, and Japanese sea salt followed by a body wrap made of Japanese rice bran, clay, yuzu (a citrus fruit packed with skin-brightening vitamin C), ginger, and pine essential oils. You can choose a 90 minute or 60 minute massage with this option. At 46,000 yen, it's certainly pricey, but you'd be hard-pressed to find a spa treatment this luxurious anywhere but here. Opening hours Sunday: Open 24 hours Monday: Open 24 hours Tuesday: Open 24 hours Wednesday: Open 24 hours Thursday: Open 24 -

Meiji Shrine 33 Harajuku Southern Tokyo

NORTHERN TOKYO CONTENTS DESTINATIONS EASTERN TOKYO SENSOJI TEMPLE SOUTHERN TOKYO WESTERN TOKYO 北部の東京 NORTHERN TOKYO SENSOJI TEMPLE SENSOJI TEMPLE SENSOJI TEMPLE SENSOJI TEMPLE SENSOJI TEMPLE NORTHERN TOKYO CONTENTS WHEN PEOPLE THINK OF TOKYO THEY THINK OF A MEGALOPOLIS TOKYO, JAPAN OF MODERN SKYSCRAPERS. THAT’S A PRETTY ACCURATE DE- CITY TRAVEL GUIDE SCRIPTION OF MOST OF TOKYO. THE EXCEPTION TO THIS ARE THE NORTHERN NEIGHBORHOODS OF ASAKUSA AND UENO. VOL. 13 JUNE 2017 02 $8.99 DESTINATIONS EASTERN TOKYO 05 SENSOJI TEMPLE EASTERN TOKYO IS LARGELY RESIDENTIAL AND INDUSTRIAL. MOST 07 TOKYO SKYTREE SIGHTS ARE CONCENTRATED IN THE SUMIDA NEIGHBORHOOD 09 EDO-MUSEUM SUCH AS TOKYO’S MAIN SUMO STADIUM RYOGOKU KOKUGIKAN. 13 AKIHABARA 15 TSUKIJI MARKET 17 KOISHIKAWA 21 TOKYO TOWER 23 ODAIBA 25 ROPPONGI HILLS 10 29 SHIBUYA 31 MEIJI SHRINE 33 HARAJUKU SOUTHERN TOKYO WITH ITS NUMEROUS SKYSCRAPERS AND DEPARTMENT STORES, SOUTHERN TOKYO IS ONE OF THE CITY’S HIPPER AREAS. THIS YOUNGER DISTRICT IS HOME TO THE LATEST FASHION, ENTER- 18 TAINMENT, FOOD AND TRENDS IN JAPAN. WESTERN TOKYO WESTERN TOKYO IS THE MOST POPULATED AREA, MOST ACTIVELY CHANGING, AND THE MOST VIBRANT AND STYLISH AREA IN TOKYO. IT IS THE DEFINITION OF THE CITY THAT NEVER SLEEPS. 26 A JOURNEY THROUGH THE FOUR MAJOR REGIONS の 考 超 東 地 例 え 高 京 域 外 て 層 を 北方 で は、い ビ 考 す。浅 ま ル え 草 す。の る と メ 人 上 ガ は、 野 ポ 近 の リ 代 北 ス 的 部 を な WHEN PEOPLE THINK OF TOKYO THEY THINK OF A MEGALOPOLIS OF MODERN SKYSCRAPERS. -

ITIN Family with 11-Year-Old Daughter, Japan June 2019

ITIN Family with 11-year-old daughter, Japan June 2019 Jizo: protector of children, found in every neighborhood in Japan Client: An American mother and father and 11-year-old daughter. This trip was 90% self guided and almost entirely focused on the interests of the daughter. June 7 (Fri): Arrive Narita International Airport on NH5 (ANA) @ 16:30 (out of LAX) at T1, south wing; you will exit customs at roughly 17:30 and then take the 18:15 Narita Express to JR Shinjuku Station (as below; only a few Narita Express trains go to Shinjuku; this one does). From Shinjuku you can take a short taxi ride to Takadanobaba Station to meet your host or go there by train: the transfer document will provide for both options: platform numbers, etc.). Hotel: AirBnB in Takadanobaba, about 3 km Your Japan Private Tours Ltd. (since 1990) | Sakyo-ku, Kyoto, Japan | Tel: +81-(0)50-5534-4372 | www.kyoto-tokyo-private-tours.com north of Shinjuku. Charges: Yen 5,000/2pax Digital A to B transfer from the airport to Takadanobaba Station. Time Route Fare Seat Fee UsefulLink • Map • Hotel NARITA AIRPORT TERMINAL 1 • Rent-a-car 18:15 Station timetable | Add to favorite Restaurant • LTD. EXP NARITA EXPRESS 44 • Reserved seat: ¥1,700 [89 Min] Train timetable | Interval timetable ¥1,490 SHINJUKU(JR) [ Arrival track No.6 ] 19:44 Add to favorite June 8 (Sat): 10:00-12:30: Nakano: this cathedral-like shotengai shopping arcade (2 km northwest of Shinjuku) is a popular haunt for Tokyo's otaku geek community. -

Japan Real Estate Investment Corporation Performance Review for the Sixth Period (Ended September 30, 2004) November 2004

Japan Real Estate Investment Corporation Performance Review for the Sixth Period (Ended September 30, 2004) November 2004 Japan Real Estate Asset Management Co. , Ltd. Ryoichi Kakehashi, President & CEO Structure of JRE D ・・・ Dividend Asset Manager I ・・・ Interest Investor Investor JaJappanan Re Real al EEststaatte e AAssssetet MMananagagemenementt Co Co., ., LLttdd. D Entrusting D D Investor Sponsorship Financial Institutions D I 36% 27% Investment & Profits from Rental Revenue Management in Real 27% Estate Daiichi Mutual Life 10% Building A Building B Building C Mitsui & Co. Points ・JRea manages the office building portfolio. ・Expertise of Mitsubishi Estate, Tokio Marine & Nichido, Daiichi Mutual Life, and Mitsui & Co. is fully utilized. ・Units are listed and traded on the Tokyo Stock Exchange. ・Dividends are regarded as an expense if over 90% of the taxable income is paid out. *The Tokio Marine and Fire Insurance Co., Ltd. and the Nichido Fire and Marine Insurance Co., Ltd. merged to form the Tokio Marine & Nichido Fire Insurance Co., Ltd. on October 1, 2004. The Four S’s Support JRE’s Growth SS incerity SS tability SS trength of will SS oundness We believe that our growth is created by “the 4 S’s”: sincerity, stability, soundness, and strength of will. Table of Contents Executive Summary l Financial Summary for the 6th Period 2・3 l Summary of Debts 4・5 l Unitholder Data (Composition and Major Unitholders) 6・7 l Property Acquisitions and Occupancy Rate after IPO 8 l Property Data ① (Price Comparison) 9 l Properties Acquired in the -

J-REIT Rating Report

Structured Finance J-REIT Rating Report Analysts Office Building Fund of Japan, Inc. Roko Izawa Tokyo (81) 3-3593-8674 [email protected] New Rating Tomoyoshi Omuro Long-term rating: A Tokyo (81) 3-3593-8584 Short-term rating: A-1 [email protected] Outlook: Stable Andrea Bryan Tokyo (81) 3-3593-8657 [email protected] Rationale Elizabeth Campbell On May 1, Standard & Poor’s assigned its ‘A’ long-term and ‘A-1’ short-term corporate credit New York (1) 212-438-2415 [email protected] ratings to Office Building Fund of Japan, Inc. (NBF). The outlook on the long-term rating is stable. The ratings are based on the following strengths: The highly regulated nature of Japanese real estate investment trusts (J-REIT); NBF’s strong business position and relatively conservative financial profile; The high quality of the real estate portfolio that generates a stable cash income stream; The excellent portfolio management capabilities of Office Building Fund Management Japan. Ltd. (NBFM), the asset management firm appointed by NBF; and The excellent property management and leasing capabilities of the property management firm. These strengths are partly offset by: The unseasoned market in which NBF operates; The company’s aggressive investment policy and growth strategy; Its portfolio’s concentration risk on larger assets, as well as tenant concentration risk; and Relatively weak credit quality of the sponsor companies. A corporate credit rating (or issuer credit rating) represents a current opinion of an obligor’s credit- June 2002 worthiness, or in short, its overall ability to pay its financial obligations. This opinion focuses on the obligor’s capacity and willingness to meet its financial commitments as they come due.