Needs Assessment Report Far North Region, Cameroon February 2016 Executive Summary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

B133 Cameroon's Far North Reconstruction Amid Ongoing Conflict

Cameroon’s Far North: Reconstruction amid Ongoing Conflict &ULVLV*URXS$IULFD%ULHILQJ1 1DLUREL%UXVVHOV2FWREHU7UDQVODWHGIURP)UHQFK I. Overview Cameroon has been officially at war with Boko Haram since May 2014. Despite a gradual lowering in the conflict’s intensity, which peaked in 2014-2015, the contin- uing violence, combined with the sharp rise in the number of suicide attacks between May and August 2017, are reminders that the jihadist movement is by no means a spent force. Since May 2014, 2,000 civilians and soldiers have been killed, in addition to the more than 1,000 people kidnapped in the Far North region. Between 1,500 and 2,100 members of Boko Haram have reportedly been killed following clashes with the Cameroonian defence forces and vigilante groups. The fight against Boko Haram has exacerbated the already-delicate economic situation for the four million inhabitants of this regionௗ–ௗthe poorest part of the country even before the outbreak of the conflict. Nevertheless, the local population’s adaptability and resilience give the Cameroonian government and the country’s international partners the opportunity to implement development policies that take account of the diversity and fluidity of the traditional economies of this border region between Nigeria and Chad. The Far North of Cameroon is a veritable crossroads of trading routes and cultures. Besides commerce, the local economy is based on agriculture, livestock farming, fishing, tourism, transportation of goods, handcrafts and hunting. The informal sector is strong, and contraband rife. Wealthy merchants and traditional chiefsௗ–ௗoften members of the ruling party and high-ranking civil servantsௗ–ௗare significant economic actors. -

Emergency Appeal Operation Update Cameroon: Population Movements

Emergency appeal operation update Cameroon: Population Movements Emergency appeal n° MDRCM021 GLIDE n° OT-2014-000172-CMR Operations update n° 2 Timeframe covered by this update:9 February to 23 March Emergency Appeal operation start Timeframe: 05 months and end date: June 2015 date: 9 February 2015 Original Appeal budget: Appeal Total estimated Red Cross and Red Crescent response to date: CHF 1,671,593 coverage: CHF 461,578 New Appeal budget: 28 % CHF 1,692,347 Disaster Relief Emergency Fund (DREF) allocated: CHF 180,000 N° of people being assisted:25,000 Host National Society(ies) (NS) presence (n° of volunteers, staff, branches): 40,000 volunteers with 18’000 active volunteers across 58 branches and 339 local committees. In Garoua Branch, there are 280 volunteers. Red Cross Red Crescent Movement partners actively involved in the operation: French Red Cross and ICRC Other partner organizations actively involved in the operation: UNHCR, UNICEF, WFP, Ministry of Health, Ministry of Territorial Administration and Decentralisation - Civil Protection, Japanese Government This update highlights an additional requests allocation of CHF 20,754, to help set up a computer room at the Cameroon Red Cross headquarters, train NS staff in the use of radio frequency and radio equipment and in security and E-learning. This represents a budget revision of less than 10% of the total amount originally allocated. Summary: Since July 2014, a large number of Nigerian refugees have been crossing the border into Cameroon, fleeing armed clashes. So far, about 35,000 refugees have been registered by UNHCR. About 30,000 internally displaced persons (IDPs) have also been reported, following clashes at the border where some villages and towns have been attacked. -

Cameroon Humanitarian Situation

Cameroon Humanitarian Situation Report No. 09 Reporting Period: September 1 – September 30 2020 Situation in Numbers Highlights 2,000,000 children in need of humanitarian assistance (UNICEF HAC 2020) • For the sixth consecutive month, UNICEF received no contribution for its humanitarian response (non-COVID-19). In Far North region, 2 attacks on 6,200,000 health facilities were reported. Only 4% of UNICEF’s response for victims people in need of Boko Haram attacks is presently funded with health and WASH sectors (HRP June 2020) worst impacted. • In the Far-North, 11,682 children and caregivers benefitted from mental 450,268 IDPs in the NWSW regions (OCHA health and psychosocial support. • In the North-West and South-West regions, UNICEF partners provided MSNA, August 2019) IYCF counselling to 48,364 parents and caregivers. 203,634 Returnees in the NW/SW • Immunization coverage to prevent child killing disease in conflict areas (OCHA December 2019) remains low, especially for measles. Urgent funds mobilization is needed to support these activities unreached through routine immunization 321,886 IDPs in the Far North program. Some 65% of children in the North-West Region are (OIM, June 2020) unvaccinated and 47% in the South-West. 123,489 Returnees in the Far North (IOM, June 2020) UNICEF’s Response and Funding Status SAM admissions 72% * UNICEF Appeal 2020 Funding Status (in US$) * Nutrition Funding status 2% * Measles vaccination 14% Requirement: $45.5m Available $7.2m (16%) Health Funding status 6% Safe water access 33% WASH Funding status 21% Carry- forward MHPSS access 56% US$ 3.4 M Received Child Funding status 26% US$ 3.8M Protection Funding gap Education access 38% US$ 38.2M Funding status 7% Education 0% 20% 40% 60% 80% 100% *achieved through non-HAC funding sources 1 Funding Overview and Partnerships In 2020 UNICEF is appealing for US$ 45,445,000 in support of lifesaving and protection-based response for children and women in Cameroon. -

Monthly Humanitarian Situation Report UNICEF CAMEROON Date: 28 October 2013

Monthly Humanitarian Situation Report UNICEF CAMEROON Date: 28th October 2013 Highlights Flash Floods in 2013: On 18th and 26th September 2013, floods were reported in Gougui, Houmi and Begue Palam Communities in the Kai-Kai subdivision in the Mayo Danay division (Far North Region) due to rupture in the Logone dam. As a result 3,108 Internally Displaced People (IDPs) have been relocated to Begue Palam. 400 families have been reached with essential WASH supplies since the beginning of the floods. UNICEF has signed a partnership with the Cameroon Red Cross to improve water quality, build 80 emergencies latrines and promote good hygiene practices among IDPs. Nigerian Refugees: A refugee camp is already established in Minawao (situated in Mayo Tsanaga division (Mokolo), some 30 km from Mokolo and 130 km from the boarder, and 75 km far from Maroua). The number of refugees living in Minawao camp has increased to 1,735 including 277 new arrivals on October 19th. WASH needs - all the 60 latrines and 30 showers planned as first WASH emergencies response have been constructed through the partnership between UNICEF and ACEEN. Education needs -UNHCR, UNICEF expedited a response package of school bags, ECD kits, recreation kits, hygiene kits (for teachers), and schools in a box for the 623 children in the camp. Nutrition needs - The screening and active case finding of acute malnutrition organized on October found that 2.27% of total screened children (n=57/2265) suffer from severe acute malnutrition and 9.7% (n=22/2265) suffer from moderate acute malnutrition. 6 new SAM cases of children started receiving treatment with therapeutic foods and drugs in the outpatient centre of Gadala. -

CAMEROON : Far North - Idps Overview 29 March 2015

CAMEROON : Far North - IDPs Overview 29 March 2015 Overview from the region Total IDP Population 96,042 Age & Gender Violent attacks by Boko Haram in Nigeria as well as in villages along the border inside Cameroon have increased during the last months. Reports by those who fled Age (Years) Male Female indicate lootings of villages, killings, mass execution, and kidnappings including of children which resulted in large scale displacement. The vast majority of the IDPs 0-4 8% 7% are reportedly staying with host communities. Latest figures shared by the 5-10 7% 7% Government with UNHCR indicate a total of 96,042 IDPs in three departments 11-14 6% 6% (Logone et Chari: 39,853; Maya Tsanaga: 29,200; Mayo Sava : 26,989). To provide timely protection and assistance to IDPs and host communities the Government 15-19 5% 5% asked UNHCR to engage in a profiling exercise which is currently underway. First 20-29 9% 9% results of the UNHCR protection assessment will be available at the end of the 30-44 8% 8% week. 49-59 4% 5% FOOD & NUTRITION 39,853 60+ 2% 3% SAM prevalence (6-59 Months) EDUCATION 120 schools were forced to close in 10 districts of the Far North for the current 2 % accademic year (2014-2015) 0% 1% 2% 3% 4% 5% 33,163 children (43% girls) are out of school or have been forced to seek access 26,989 to schooling outside of their native communities as a result of school closures in The Far North region has a prevalence of severe acute malnutrition (SAM) of 2.0% affected districts corresponding to the emergency threshold. -

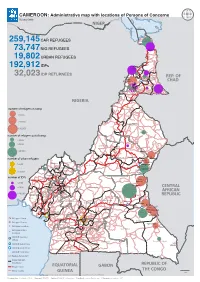

CAMEROON: Administrative Map with Locations of Persons of Concerns October 2016 NIGER Lake Chad

CAMEROON: Administrative map with locations of Persons of Concerns October 2016 NIGER Lake Chad 259,145 CAR REFUGEES Logone-Et-Chari 73,747 NIG REFUGEES Kousseri 19,802 URBAN REFUGEES Waza IDPs Limani 192,912 Magdeme Mora Mayo-Sava IDP RETURNEES Diamare 32,023 Mokolo REP. OF Gawar EXTREME-NORD Minawao Maroua CHAD Mayo-Tsanaga Mayo-Kani Mayo-Danay Mayo-Louti NIGERIA number of refugees in camp Benoue >5000 >15000 NORD Faro >20,000 Mayo-Rey number of refugees out of camp >3000 >5000 Faro-et-Deo Beke chantier >20,000 Vina Ndip Beka Borgop Nyambaka number of urban refugees ADAMAOUA Djohong Ngam Gbata Alhamdou Menchum Donga-Mantung >5000 Meiganga Mayo-Banyo Djerem Mbere Kounde Gadi Akwaya NORD-OUEST Gbatoua Boyo Bui Foulbe <10,000 Mbale Momo Mezam number of IDPs Ngo-ketunjia Manyu Gado Bamboutos Badzere <2000 Lebialem Noun Mifi Sodenou >5000 Menoua OUEST Mbam-et-Kim CENTRAL Hauts-Plateaux Lom-Et-Djerem Kupe-Manenguba Koung-Khi AFRICAN >20,000 Haut-Nkam SUD-OUEST Nde REPUBLIC Ndian Haute-Sanaga Mbam-et-Inoubou Moinam Meme CENTRE Timangolo Bertoua Bombe Sandji1 Nkam Batouri Pana Moungo Mbile Sandji2 Lolo Fako LITTORAL Lekie Kadei Douala Mefou-et-Afamba Mbombete Wouri Yola Refugee Camp Sanaga-Maritime Yaounde Mfoundi Nyong-et-Mfoumou EST Refugee Center Nyong-et-Kelle Mefou-et-Akono Ngari-singo Refugee Location Mboy Haut-Nyong Refugee Urban Nyong-et-So Location UNHCR Country Ocean Office Mvila SUD Dja-Et-Lobo Boumba-Et-Ngoko Bela UNHCR Sub-Office Libongo UNHCR Field Office Vallee-du-Ntem UNHCR Field Unit Region Boundary Departement boundary REPUBLIC OF Major roads EQUATORIAL GABON Minor roads THE CONGO GUINEA 50km The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. -

Mayo-Sava, Mayo-Tsanaga Et Logone Et Chari

RAPPORT DE LA MISSION DE SUPERVISION CONJOINTE AHA-DS MOKOLO, DS KOZA, DS MORA, DS KOLOFATA ET DS Makary- OMS- DRSP/EN DANS LE CADRE Du 1 PROGRAMME D’APPUI D’URGENCE eN SANTE DANS LES DEPARTEMENTS DU MAYO-SAVA, MAYO-TSANAGA ET LOGONE ET CHARI Photo AHA : Photo de famille après la supervision des activités Au CMA de Fotokol Du 29 Octobre 2018 au 09 Novembre 2018 Représentation nationale : Bastos-Yaoundé à coté du Palais des Congrès, BP : 1428 - Yaoundé Tel: (+237) 243 57 28 15 / 678 78 39 96 / 693 99 74 09/(00236) 75 05 14 66 E-mail: [email protected] / [email protected]/ [email protected] Website: www.aha-afric.org Sommaire Sommaire ----------------------------------------------------------------- 2 2 1. Résume . -------------------------------------------------------------- 3 2. Introduction ---------------------------------------------------------- 4 3. OBJECTIFS ------------------------------------------------------------ 5 3.1. Objectif Principal : ---------------------------------------------------- 5 3.2. Objectifs spécifiques ------------------------------------------------- 5 4.1 Description de la méthodologie -------------------------------------- 5 4.7 Defis et contraintes -------------------------------------------------- 5 5 Résultats -------------------------------------------------------------- 5 6. Principales recommandations ----------------------------------------- 9 7 Annexes. ------------------------------------------------------------- 10 Représentation nationale : Bastos-Yaoundé à coté du Palais des Congrès, BP : 1428 - Yaoundé Tel: (+237) 243 57 28 15 / 678 78 39 96 / 693 99 74 09/(00236) 75 05 14 66 E-mail: [email protected] / [email protected]/ [email protected] Website: www.aha-afric.org Les Départements du Mayo-sava, Mayo-tsanaga et Logone et Chari situés à la frontière avec le Tchad et le Nigéria sont les départements les plus affectés par la crise 3 humanitaire que connait la partie septentrionale du Cameroun du fait des exactions du groupe terroriste Boko Haram et d’autres aléas naturels propres à ces zones. -

Cameroon: Administrative Map with Locations of Persons of Concerns; October 2016

CAMEROON: Administrative map with locations of Persons of Concerns October 2016 NIGER Lake Chad 259,145 CAR REFUGEES Logone-Et-Chari 73,747 NIG REFUGEES Kousseri 19,802 URBAN REFUGEES Waza IDPs Limani 192,912 Magdeme Mora Mayo-Sava IDP RETURNEES Diamare 32,023 Mokolo REP. OF Gawar EXTREME-NORD Minawao Maroua CHAD Mayo-Tsanaga Mayo-Kani Mayo-Danay Mayo-Louti NIGERIA number of refugees in camp Benoue >5000 >15000 NORD Faro >20,000 Mayo-Rey number of refugees out of camp >3000 >5000 Faro-et-Deo Beke chantier >20,000 Vina Ndip Beka Borgop Nyambaka number of urban refugees ADAMAOUA Djohong Ngam Gbata Alhamdou Menchum Donga-Mantung >5000 Meiganga Mayo-Banyo Djerem Mbere Kounde Gadi Akwaya NORD-OUEST Gbatoua Boyo Bui Foulbe <10,000 Mbale Momo Mezam number of IDPs Ngo-ketunjia Manyu Gado Bamboutos Badzere <2000 Lebialem Noun Mifi Sodenou >5000 Menoua OUEST Mbam-et-Kim CENTRAL Hauts-Plateaux Lom-Et-Djerem Kupe-Manenguba Koung-Khi AFRICAN >20,000 Haut-Nkam SUD-OUEST Nde REPUBLIC Ndian Haute-Sanaga Mbam-et-Inoubou Moinam Meme CENTRE Timangolo Bertoua Bombe Sandji1 Nkam Batouri Pana Moungo Mbile Sandji2 Lolo Fako LITTORAL Lekie Kadei Douala Mefou-et-Afamba Mbombete Wouri Yola Refugee Camp Sanaga-Maritime Yaounde Mfoundi Nyong-et-Mfoumou EST Refugee Center Nyong-et-Kelle Mefou-et-Akono Ngari-singo Refugee Location Mboy Haut-Nyong Refugee Urban Nyong-et-So Location UNHCR Country Ocean Office Mvila SUD Dja-Et-Lobo Boumba-Et-Ngoko Bela UNHCR Sub-Office Libongo UNHCR Field Office Vallee-du-Ntem UNHCR Field Unit Region Boundary Departement boundary REPUBLIC OF Major roads EQUATORIAL GABON Minor roads THE CONGO GUINEA 50km The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. -

Cameroon: Cholera in GLIDE N° EP-2010-000110-CMR Update N° 1 Northern Cameroon 6 August, 2010 DREF Budget and Timeframe Extension

DREF operation n° MDRCM009 Cameroon: Cholera in GLIDE n° EP-2010-000110-CMR Update n° 1 Northern Cameroon 6 August, 2010 DREF budget and timeframe extension The International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent (IFRC) Disaster Relief Emergency Fund (DREF) is a source of un-earmarked money created by the Federation in 1985 to ensure that immediate financial support is available for Red Cross and Red Crescent emergency response. The DREF is a vital part of the International Federation’s disaster response system and increases the ability of National Societies to respond to disasters. Period covered by this update: 11 June to 5 August 2010 Summary: CHF 141,474 was allocated from the IFRC’s Disaster Relief Emergency Fund (DREF) on 11 June 2010 to support the Cameroon Red Cross National Society in delivering assistance to some 800,000 beneficiaries. Since July, ten more health districts have been affected and the Cameroon Red Cross volunteers are carrying out social mobilization in 8 of the 14 health districts concerned. So far, 1,456 cases of cholera and 109 deaths have already been registered, which represents a This place has been chosen as a temporary cholera treatment serious increase of the number of cases centre (Mokolo) managed by Cameroon Red Cross volunteers and deaths compared to those at the Genevieve PIAM – Regional Disaster Response Team. time this DREF operation was launched. A DREF extension of CHF 239,680 has therefore been made to extend the operation from 800,000 3,480,000 beneficiaries and bringing the total DREF allocation to CHF 381,154. -

Cameroon Humanitarian Situation Report

Cameroon Humanitarian Situation Report SITUATION IN NUMBERS March 2018 Highlights 1,810,000 • UNOCHA-led interagency assessment mission identified # of children in need of humanitarian estimated 40,000 IDPs in Mamfe and Mbonge/Kumba sub- assistance 3,260,000 divisions of South West region. The total number of IDPs is # of people in need expected to be substantially higher as the assessment mission (Cameroon Humanitarian Needs Overview 2018) was unable to visit many areas due to access constraints. • Over 2.3 million children under five years of age including Displacement 241,000 refugee and IDP children were vaccinated against polio and #of Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs) received vitamin A and mebendazole (deworming tablets) in Far (Displacement Tracking Matrix 12, Dec 2017) North, East and Adamaoua regions. 69,700 # of Returnees • The awareness activities through educational sessions and (Displacement Tracking Matrix 12, Dec 2017) theatre presentations reached 30,709 IDPs and members of the 87,600 # of Nigerian Refugees in rural areas host communities in Far North region promoting Essential (UNHCR Cameroon Fact Sheet, Mar 2018) Family Practices. 232,100 # of CAR Refugees in East, Adamaoua and North UNICEF’s Response with Partners regions in rural areas (UNHCR Cameroon Fact Sheet, March 2018) Sector UNICEF Sector Total UNICEF Total UNICEF Appeal 2018 Target Results* Target Results* US$ 25.4 million WASH : People provided with 528,000 8,907 75,000 8,897 access to appropriate sanitation Funding status 2018 Education: School-aged children 4- 17, including adolescents, accessing (US$) 411,000 9,911 280,000 9,911 2017 Carry- education in a safe and protective over: $2.1M learning environment. -

Traditional Techniques of Oil Extraction from Kapok (Ceiba Pentandra Gaertn.), Mahogany (Khaya Senegalensis) and Neem (Azadirach Indica A

International Journal of Environment, Agriculture and Biotechnology (IJEAB) Vol-2, Issue-4, July -Aug- 2017 http://dx.doi.org/10.22161/ijeab/2.4.81 ISSN: 2456-1878 Traditional Techniques of oil extraction from Kapok (Ceiba pentandra Gaertn.), Mahogany (Khaya senegalensis) and Neem (Azadirach indica A. Juss.) Seeds from the Far-North Region of cameroon Gilles Bernard Nkouam1*, Balike Musongo1, Armand Abdou Bouba2, Jean Bosco Tchatchueng3, César Kapseu4, Danielle Barth5 1Department of Refining end Petrochemistry, Faculty of Mines and Petroleum Industries, The University of Maroua, P.O.Box. 08 Kaele, Cameroon, Tel: +237 696 33 85 03 / 662 999 397, email: [email protected] 2Department of Agriculture, Livestock and Derived Products, National Advanced Polytechnic School of Maroua, The University of Maroua, P.O.Box 46 Maroua, Cameroon 3Department of Applied Chemistry, National Advanced School of Agro-Industrial Sciences, The University of Ngaoundere, P. O. Box 455 Ngaoundere, Cameroon 4Department of Process Engineering, National Advanced School of Agro-Industrial Sciences, The University of Ngaoundere, P. O. Box 455 Ngaoundere, Cameroon 5Laboratoire Réactions et Génie des Procédés UMR CNRS 7274 ENSIC-INPL, 1, rue Grandville BP20451 54001 Nancy, France * Corresponding author Abstract—An investigation was carried out in four properties. They are used as a mixture or individually. localities of the Far-North of Cameroon (Maroua, Locally, these oils serve in the treatment of various Mokolo, Kaele and Yagoua in order to improve diseases such as constipation, diarrhea, malaria, typhoid, endogenous methods of oil extraction from kapok (Ceiba worms and hemorrhoids [1, 2]. Neem oil is equally pentandra Gaertn.), mahogany (Hhaya senegalensis) and applied as a pomade to treat "getti getti" [3, 4]. -

WEEKLY BULLETIN on OUTBREAKS and OTHER EMERGENCIES Week 3: 13 - 19 January 2020 Data As Reported By: 17:00; 19 January 2020

WEEKLY BULLETIN ON OUTBREAKS AND OTHER EMERGENCIES Week 3: 13 - 19 January 2020 Data as reported by: 17:00; 19 January 2020 REGIONAL OFFICE FOR Africa WHO Health Emergencies Programme 1 67 53 15 New event Ongoing events Outbreaks Humanitarian crises 1 215 0 20 0 2 0 10 207 55 Senegal Mali Niger 26 623 259 1 0 41 7 1 251 0 336 7 Guinea Burkina Faso 52 0 Chad 4 690 18 26 2 2 089 21 Côte d’Ivoire Nigeria Sierra léone 9 0 895 15 South Sudan Ethiopia 812 181 137 2 9 672 7 4 Ghana 3 787 192 Cameroon Central African 5 0 Liberia 4 414 23 Benin Republic 16 0 54 908 0 58 916 289 1 307 55 2 904 49 Togo 1 170 14 2 1 Democratic Republic Uganda 79 20 1 692 5 3 0 1 0 510 1 of Congo 5 150 39 78 13 Congo 3 412 2 237 2 2 Kenya Legend 6 0 2 879 34 316 550 6 102 Measles Humanitarian crisis 11 434 0 29 087 501 Burundi Hepatitis E 8 724 857 3 233 Monkeypox 84 0 1 064 6 Yellow fever Lassa fever 51 8 Dengue fever Cholera Angola 5 117 104 Ebola virus disease Rift Valley Fever Comoros 71 0 2 0 Chikungunya 218 0 cVDPV2 Zambia Leishmaniasis Malaria Floods Plague Cases Meningitis Namibia Deaths Countries reported in the document Non WHO African Region 6 974 59 WHO Member States with no reported events N W E 3 0 Lesotho 59 0 South Africa 20 0 S Graded events † 3 14 1 Grade 3 events Grade 2 events Grade 1 events 43 22 20 31 Ungraded events PB ProtractedProtracted 3 3 events events Protracted 2 events ProtractedProtracted 1 1 events event 1 Health Emergency Information and Risk Assessment Health Emergency Information and Risk Assessment Health Emergency Information and Risk Assessment Overview This Weekly Bulletin focuses on public health emergencies occurring in the WHO Contents African Region.