Revelation and the Left Behind Novels Craig R

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In the Event of Global Vanishings – Please Read

In the Event of Global Vanishings – Please Read To: A Concerned Person who has no doubt been LEFT BEHIND. From: Pastor Rob Lee Re: Instructions on just what to do, and not do, right now. The fact that you are reading this tells me that you have experienced a traumatic event that has taken place. Millions of people all over the face of the earth have mysteriously disappeared. Millions of men, women, children, toddlers, infants, and even unborn babies are now gone. Although widespread panic has most likely accompanied this phenomenal event, there is an explanation. Please read the following. I am sure by now people are saying that it was UFO’s, aliens from another planet, or a change in the evolutionary process; a ‘selective elimination’ of sorts that caused the disappearances. Some may be saying that the global vanishings were caused by some kind of high-tech weapon that can vaporize people, and children are more susceptible to it. Perhaps there are many other crazy theories. The bottom-line fact is that Jesus Christ has returned for His Church just as He said He would. Just find a Bible and read the following passages: • 1 Thessalonians 4:16-17 – Referring to the “catching away” of the saints. • 1 Corinthians 15:51-54 – Referring to those who “shall not all sleep.” • John 11:25-26 – Referring to the Resurrection of Christ’s Church This is an event that has been prophesied in both the Old Testament and New Testament books of the Bible. Many pastors, teachers, scholars, and Christians have also believed in this global rapture event. -

978-1-4143-3501-8.Pdf

Tyndale House Novels by Jerry B. Jenkins Riven Midnight Clear (with Dallas Jenkins) Soon Silenced Shadowed The Last Operative The Brotherhood The Left Behind® series (with Tim LaHaye) Left Behind® Desecration Tribulation Force The Remnant Nicolae Armageddon Soul Harvest Glorious Appearing Apollyon The Rising Assassins The Regime The Indwelling The Rapture The Mark Kingdom Come Left Behind Collectors Edition Rapture’s Witness (books 1–3) Deceiver’s Game (books 4–6) Evil’s Edge (books 7–9) World’s End (books 10–12) For the latest information on Left Behind products, visit www.leftbehind.com. For the latest information on Tyndale fiction, visit www.tyndalefiction.com. 5*.-")":& +&33:#+&/,*/4 5:/%"-&)064&16#-*4)&34 */$ $"30-453&". *--*/0*4 Visit Tyndale’s exciting Web site at www.tyndale.com. Discover the latest about the Left Behind series at www.leftbehind.com. TYNDALE, Tyndale’s quill logo, and Left Behind are registered trademarks of Tyndale House Publishers, Inc. Glorious Appearing: The End of Days Copyright © 2004 by Tim LaHaye and Jerry B. Jenkins. All rights reserved. Cover photograph copyright © by Valentin Casarsa/iStockphoto. All rights reserved. Israel map © by Maps.com. All rights reserved. Author photo of Jerry B. Jenkins copyright © 2010 by Jim Whitmer Photography. All rights reserved. Author photo of Tim LaHaye copyright © 2004 by Brian MacDonald. All rights reserved. Left Behind series designed by Erik M. Peterson Published in association with the literary agency of Alive Communications, Inc., 7680 Goddard Street, Suite 200, Colorado Springs, CO 80920. www.alivecommunications.com. Scripture quotations are taken or adapted from the New King James Version.® Copyright © 1982 by Thomas Nelson, Inc. -

Millennialism, Rapture and “Left Behind” Literature. Analysing a Major Cultural Phenomenon in Recent Times

start page: 163 Stellenbosch Theological Journal 2019, Vol 5, No 1, 163–190 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.17570/stj.2019.v5n1.a09 Online ISSN 2413-9467 | Print ISSN 2413-9459 2019 © Pieter de Waal Neethling Trust Millennialism, rapture and “Left Behind” literature. Analysing a major cultural phenomenon in recent times De Villers, Pieter GR University of the Free State, Bloemfontein, South Africa [email protected] Abstract This article represents a research overview of the nature, historical roots, social contexts and growth of millennialism as a remarkable religious and cultural phenomenon in modern times. It firstly investigates the notions of eschatology, millennialism and rapture that characterize millennialism. It then analyses how and why millennialism that seems to have been a marginal phenomenon, became prominent in the United States through the evangelistic activities of Darby, initially an unknown pastor of a minuscule faith community from England and later a household name in the global religious discourse. It analyses how millennialism grew to play a key role in the religious, social and political discourse of the twentieth century. It finally analyses how Darby’s ideas are illuminated when they are placed within the context of modern England in the sixteenth, seventeenth and eighteenth century. In a conclusion some key challenges of the place and role of millennialism as a movement that reasserts itself continuously, are spelled out in the light of this history. Keywords Eschatology; millennialism; chiliasm; rapture; dispensationalism; J.N. Darby; Joseph Mede; Johann Heinrich Alsted; “Left Behind” literature. 1. Eschatology and millennialism Christianity is essentially an eschatological movement that proclaims the fulfilment of the divine promises in Hebrew Scriptures in the earthly ministry of Christ, but it also harbours the expectation of an ultimate fulfilment of Christ’s second coming with the new world of God that will replace the existing evil dispensation. -

Tim Lahaye 9 – Desecration

The Left Behind* series Left Behind Tribulation Force Nicolae Soul Harvest Apollyon Assassins The Indwelling The Mark Desecration Book 10-available summer 2002 ANTICHRIST TAKES THE THRONE DESECRATION #1: The Vanishings #2: Second Chance #3: Through the Flames #4: Facing the Future #5: Nicolae High #6: The Underground #7: Busted! #8: Death Strike #9: The Search Left Behind(r): The Kids #10: On the Run #11: Into the Storm #12: Earthquake! #13: The Showdown #14: Judgment Day #15: Battling the Commander #16: Fire from Heaven #17: Terror in the Stadium #18: Darkening Skies Special FORTY-TWO MONTHS INTO THE TRIBULATION; TWENTY-FIVE DAYS INTO THE GREAT TRIBULATION The Believers Rayford Steele, mid-forties; former 747 captain for Pan-Continental; lost wife and son in the Rapture; former pilot for Global Community Potentate Nicolae Carpathia; original member of the Tribulation Force; international fugitive; on assignment at Mizpe Ramon in the Negev Desert, center for Operation Eagle Cameron ("Buck") Williams, early thirties; former senior writer for Global Weekly; former publisher of Global Community Weekly for Carpathia; original member of the Trib Force; editor of cybermagazine The Truth; fugitive; incognito at the King David Hotel, Jerusalem Chloe Steele Williams, early twenties; former student, Stanford University; lost mother and brother in the Rapture; daughter of Rayford; wife of Buck; mother of fifteen-month-old Kenny Bruce; CEO of International Commodity Co-op, an underground network of believers; original Trib Force member; fugitive in exile, Strong Building, Chicago Tsion Ben-Judah, late forties; former rabbinical scholar and Israeli statesman; revealed belief in Jesus as the Messiah on international TV-wife and two teenagers subsequently murdered; escaped to U.S.; spiritual leader and teacher of the Trib Force; cyberaudience of more than a billion daily; fugitive in exile, Strong Building, Chicago Dr. -

Best Evidence We're in the Last Days

October 21, 2017 Best Evidence We’re In the Last Days Shawn Nelson Can we know when Jesus is coming back? Some people have tried to predict exactly when Jesus would come back. For example, Harold Camping predicted Sep. 6, 1994, May 21, 2011 and Oct. 21 2011. There have been many others.1 But the Bible says we cannot know exact time: Matthew 24:36 --- “But of that day and hour no one knows, not even the angels of heaven, but My Father only.” Acts 1:7 --- “And He said to them, “It is not for you to know times or seasons which the Father has put in His own authority.” We might not know the exact time, but we can certainly see the stage is being set: Matthew 16:2-3 --- ‘He answered and said to them, “When it is evening you say, ‘It will be fair weather, for the sky is red’; and in the morning, ‘It will be foul weather today, for the sky is red and threatening.’ Hypocrites! [speaking to Pharisees about events of his 1st coming] You know how to discern the face of the sky, but you cannot discern the signs of the times.’ 1 Thessalonians 5:5-6 --- “5 But concerning the times and the seasons, brethren, you have no need that I should write to you. 2 For you yourselves know perfectly that the day of the Lord so comes as a thief in the night… 4 But you, brethren, are not in darkness, so that this Day should overtake you as a thief. -

Jesus Is Coming Back with His Saints

Series: The Glorious Appearing 3. Destroy the Saints (Rev 13:7a) (Rev 6:9-11) (Rev 7:13-17) Title: The Beasts (Dan 8:24) he shall destroy the mighty and the holy people. Text: (Revelation 13:1-18) (Dan 7:21, 25) made war with the saints, and prevailed (Dan 12:9-10) Many shall be purified, made white, tried; Jesus is Coming Back WITH His Saints They will be Beheaded! (Rev 20:4) (Heb 12:3-4) (Matt 24:36) But of that day and hour knoweth no man, (Matt 25:13) Watch therefore, 4. Dominate Society: (Rev 13:7b) (Dan 8:23, 25) 5. Delude Sinners: (Rev 13:8) The devil wants converts! I. The Beast From the Sea: (Vs 1-8) His Debut: (Vs 1) He has many names, or Aliases. (Vs 9-10) Warning to Tribulation Saints who read the bible. Beast Man of Sin, Mystery of Iniquity, Son of Perdition The Little Horn, The Antichrist. II. The Beast From the Earth: (Vs 11-18) This is The False Prophet: (Rev 16:13) (Rev 19:20; 20:10) “and saw a beast rise up out of the sea,” (Rev 17:15) “having seven heads” (Rev 17:9) 1. The Masquerade: (Vs 11-12) “10 horns, 10 crowns” (Rev 17:12) (Dan 7:24) Jesus warned us of this event: (Matt 24:24) He will exalt the Beast: (Rev 13:12) His Description: (Rev 13:2a) The Beast will be the son of Satan: (Gen 3:15) Seed of Satan 2. The Miracles: (Vs 13-15) The Stateliness of the Lion: Babylon The Purpose of the Miracles: (Rev 13:14; 16:14, 19:20) The Strength of the Bear: Medo-Persion But for the Lost…. -

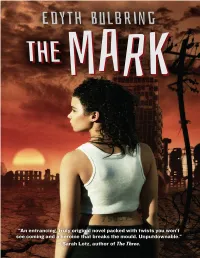

The Mark Edyth Bulbring

The Mark Edyth Bulbring Tafelberg For Charlotte, who loves stories PART ONE My name is Juliet Seven. The date is 264 PC. This year, I am going to wipe out my father and my sister. And then I will off myself. The Machine will record that I lived for fifteen years, worked as a drudge, and that my last address was Room 33, Section D, Slum City. Everything I do this year was spoken of before I existed. And it will be written in the blood of those who survive me. 1 The Monster A man flails in the breakers, thrashing the sea with windmill arms. “Monster!” he shouts. The Market Nags are the first to come screaming out of the shallows, breasts bouncing free from their underwear. “Mons ter, it’s a monster!” They swirl in circles on the beach, looking for a place to hide. The monster siren pierces the squeals of children being pulled from the breakers by beach wardens waving swimmers towards the dunes. “Get out of the water. Get out!” Their eyes scan the sea. Sun-worshippers jerk free of their torpor and abandon towels and bags. They stumble for the shelter of the dunes, dragging children along with them. “Run. Before the monster gets you. Run!” They urge toddlers along, slapping their blistered legs. The Market Nags gather their wits and clothes scattered on the beach, and follow them to safety. Glee swells my chest as I watch these fools. Buzzing around like flies trapped crazy behind a mesh screen. The sand trickles through my fingers as I wait for my moment. -

The Rapture and the Book of Revelation

TMSJ 13/2 (Fall 2002) 215-239 THE RAPTURE AND THE BOOK OF REVELATION Keith H. Essex Assistant Professor of Bible Exposition The relevance of the book of Revelation to the issue of the timing of the rapture is unquestioned. Assumptions common to many who participate in discussing the issue include the authorship of the book by John the apostle, the date of its writing in the last decade of the first century A.D., and the book’s prophetic nature in continuation of OT prophecies related to national Israel. Ten proposed references to the rapture in Revelation include Rev 3:10-11; 4:1-2; 4:4 and 5:9-10; 6:2; 7:9-17; 11:3-12; 11:15-19; 12:5; 14:14-16; and 20:4. An evaluation of these ten leads to Rev 3:10-11 as the only passage in Revelation to speak of the rapture. Rightly understood, that passage implicitly supports a pretribulational rapture of the church. That understanding of the passage fits well into the context of the message to the church at Philadelphia. * * * * * “As the major book of prophecy in the NT, Revelation has great pertinence to discussion of the rapture.”1 Participants in the discussion concerning the timing of the rapture would concur with this statement. Proponents of a pretribulational, midtribulational, pre-wrath, and posttribulational rapture all seek support for their positions in the book of Revelation.2 Many suggestions as to where Revelation 1Robert H. Gundry, The Church and the Tribulation (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1973) 64. 2Many books dealing with the rapture include sections specifically discussing the book of Revelation. -

No Longer Left Behind 211

09chap9.qxd 10/1/02 10:21 AM Page 209 No Longer Left Behind Amazon.com, Reader-Response, and the Changing Fortunes of the Christian Novel in America Paul C. Gutjahr Much ink has been spilled on the topic of the uneasy relationship between American Christians and the novel. The vast majority of this scholarship has centered on American Protestantism’s antagonism toward the novel in the early nineteenth century. With few exceptions, the dominant narrative of this relationship goes something like this: American Protestants viewed Wction writing in general, and the novel in particular, as a serious threat to the virtue and well-being of every American up until the 1850s, when their opposition began to gradually erode until it was washed away com- pletely by the astounding popularity of Lew Wallace’s Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ, Wrst published in 1880.1 As with so many grand narratives, this one is Xawed. American Protes- tantism has never been a monolithic entity. It has varied according to region- alism, denominationalism, and its connections to other American cultural practices such as science, education, and politics. Perhaps the most im- portant, and most ignored, part of this accepted narrative centers on how The author would like to gratefully acknowledge two fellowship grants that helped bring this article to completion. These grants were awarded by the Center for the Study of Religion at Princeton University under the directorship of Robert Wuthnow and Marie GrifWth and the Christian Scholars Foundation under the directorship of Bernard Draper. 09chap9.qxd 10/1/02 10:21 AM Page 210 210 Book History inXuential conservative elements within American Protestantism continued to show a distrust toward the novel through much of the twentieth century. -

The Invention of the Rapture

CHAPTER 2 The Invention of the Rapture EN-YEAR-OLD “JOSH” CAME HOME from school to an Tempty house. His mother, normally at home to greet him, was nowhere to be found. She might have been at the store or at a neighbor’s, but Josh was terrified. His immediate response was a terrible fear that all his family had been “Raptured” without him. Josh was sure he had been left behind. Now a grown-up in my seminary class on the book of Revela- tion, Josh told this story of his boyhood experience. Others consis- tently echo his story of childhood fear of the Rapture. These born- again Christian children were exhorted to be good so that they would be sure to be snatched up to heaven with Jesus when he returned. Raised on a daily diet of fear, their view of God resem- bled the song about Santa Claus coming to town: “You’d better watch out, you’d better not cry.” Only it was Jesus, not Santa, who was “coming to town” at an unexpected hour: “He knows when you’ve been sleeping. He knows when you’re awake. He knows if you’ve been bad or good, so be good for goodness sake.” 19 Copyright © 2007. Basic Books. All rights reserved. © 2007. Basic Books. Copyright Rossing, Barbara R.. The Rapture Exposed : The Message of Hope in the Book of Revelation, Basic Books, 2007. ProQuest Ebook Central, http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/washington/detail.action?docID=879536. Created from washington on 2017-12-29 12:02:16. -

Tribulation Force: the Continuing Drama of Those Left Behind by Tim Lahaye and Jerry B

Tribulation Force: The Continuing Drama of Those Left Behind by Tim LaHaye and Jerry B. Jenkins Tyndale House Publishers, Inc., 1996 $12.99, 450 pages ISBN: 08423-2921-8 A Domestic Apocalypse This is the second installment in the Left Behind series. These novels are set in the Last Days and deal, as the name suggests, with those left behind by the pre-tribulation rapture of the saints. Apocalyptic novels based on similar assumptions have been proliferating in recent years (the earliest ones, according to Paul Boyer, appeared in the 1930s), and for their intended readership terms like pre-tribulation rapture require no explanation. However, for this review a few words of explanation might be in order. The eschatological system which the novels presuppose has been increasingly influential in evangelical circles since the end of the Civil War. As the 20th century ends, it may be the most popular Christian eschatological system of any description. To put the matter briefly, pre-tribulationists hold that the saints, meaning all people who have been saved, will be miraculously removed (raptured) from the world in the years leading up to the disastrous events that precede the Second Coming of Christ. These disasters will for the most part occur in a period called the tribulation, which is most commonly expected to last seven years. During that time, the world will be ruled by Antichrist, who will persecute the new crop of saints that rises up in the wake of the rapture. He will also first make peace with the Jews, and then seek to destroy them. -

Mark 202 1 Edition Dr

Notes on Mark 202 1 Edition Dr. Thomas L. Constable WRITER The writer did not identify himself by name anywhere in this Gospel. This is true of all four Gospels. "The title, 'According to Mark' (… [kata Markon]), was probably added when the canonical gospels were collected and there was need to distinguish Mark's version of the gospel from the others. The gospel titles are generally thought to have been added in the second century but may have been added much earlier. Certainly we may say that the title indicates that by A.D. 125 or so an important segment of the early church thought that a person named Mark wrote the second gospel."1 There are many statements of the early church fathers that identify the "John Mark" who is frequently mentioned in the New Testament as the writer. The earliest reference of this type is in Eusebius' Ecclesiastical History (ca. A.D. 326).2 Eusebius quoted Papius' Exegesis of the Lord's Oracles (ca. A.D. 140), a work now lost. Papius quoted "the Elder," probably the Apostle John, who said the following things about this Gospel: Mark wrote it, though he was not a disciple of Jesus during Jesus' ministry or an eyewitness of Jesus' ministry. He accompanied the Apostle Peter and listened to his preaching. He based his Gospel on the eyewitness account and spoken ministry of Peter. 1Donald A. Carson and Douglas J. Moo, An Introduction to the New Testament, p. 172. See ibid, pp. 726-43 for a brief discussion of the formation of the New Testament canon.