Map 1. Survey Provinces in Administrative Map of Vietnam

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Second Health Care in the Central Highlands Project in Kon Tum

Due Diligence Report Project number: 44265-013 Stage: Final August 2016 VIE: Second Health Care in the Central Highlands Project in Kon Tum Province Prepared by the Ministry of Health, Socialist Republic of Viet Nam, for Asian Development Bank. The Due Diligence Report is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of March 2016) Currency unit – Vietnamese Dong (VND) $1.00 = VND 22,350 ACCRONYMS ADB - Asian Development Bank CHS - Commune Health Station CPMU - Central Project Management Unit EGP - Ethnic Group Plan HICH - Health Care in the Central Highlands Project IEC - Information, Education and Communication ICP - Inter-communal Polyclinics IMR - Infant Mortality Rate MDG - Millennium Development Goal MMR - Maternal Mortality Ratio MOH - Ministry of Health MOF - Ministry of Finance NGO - Non-Government Organization PAM - Project Administration Manual PCR - Project Completion Report PHC - Primary Health Care PPMU - Provincial Project Management Unit U5MR - Under-five mortality Rate VHW - Village Health Worker VSS - Vietnam Social Security System Notes: The Due Diligence Report is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. -

The Biogeography of the Butterfly Fauna of Vietnam with a Focus on the Endemic Species (Lepidoptera)

Chapter 5 The Biogeography of the Butterfly Fauna of Vietnam With a Focus on the Endemic Species (Lepidoptera) A.L. Monastyrskii and J.D. Holloway Additional information is available at the end of the chapter http://dx.doi.org/10.5772/55490 1. Introduction Long term studies of Vietnamese Rhopalocera suggest that by using a taxonomic composition analysis of the modern fauna, with ecological and biogeographical characteristics and comparative data with butterfly faunas of adjacent regions, it is possible to offer a plausible account of the history and derivation of the Vietnamese fauna. In former works on the butterfly fauna of Vietnam and of the Oriental tropics generally, we completed the first steps in understanding possible derivation mechanisms for the group. In particular, all Vietnamese butterfly species have been classified according to their global geographical ranges (Holloway, 1973; 1974; Spitzer et al., 1993; Monastyrskii, 2006; 2007), from the most restricted to the most widespread (Methods). A similar approach for notodontid moths in Thailand has been adopted by Schintlmeister & Pinratana (2007). Moreover, depending on the representation of various species distribution range categories, a scheme of biogeographical zonation has been suggested (Monastyrskii, 2006; 2007). In continuing studies on the specificity and derivation of the modern Vietnam butterfly fauna, aspects of species range configuration and other parameters of butterfly distribu‐ tions are considered in the current work. For example, it is possible to assign genera to groups according to both their overall range and variation of their species-richness across that range (Holloway, 1969, 1974) or according to representation of particular species range types within the genera (Holloway, 1998). -

An Analysis of the Situation of Children and Women in Kon Tum Province

PEOPLE’S COMMITTEE OF KON TUM PROVINCE AN ANALYSIS OF THE SITUATION OF CHILDREN AND WOMEN IN KON TUM PROVINCE AN ANALYSIS OF THE SITUATION OF CHILDREN 1 AND WOMEN IN KON TUM PROVINCE OF THE SITUATION OF CHILDREN AND WOMEN IN KON TUM PROVINCE AN ANALYSIS OF THE SITUATION OF CHILDREN AND WOMEN IN KON TUM PROVINCE AckNOWLEDGEMENTS This Situation Analysis was undertaken in 2013-2014 as part of the Social Policy and Governance Programme, under the framework of the Country Programme of Cooperation between the Government of Viet Nam and UNICEF in the period 2012-2016. This publication exemplifies the strong partnership between Kon Tum Province and UNICEF Viet Nam. The research was completed by a research team consisting of Edwin Shanks, Buon Krong Tuyet Nhung and Duong Quoc Hung with support from Vu Van Dam and Pham Ngoc Ha. Findings of the research were arrived at following intensive consultations with local stakeholders, during fieldwork in early 2013 and a consultation workshop in Kon Tum in July 2014. Inputs were received from experts from relevant provincial line departments, agencies and other organisations, including the People’s Council, the Provincial Communist Party, the Department of Planning and Investment, the Department of Labour, Invalids and Social Affairs, the Department of Education, the Department of Health, the Provincial Statistics Office, the Department of Finance, the Social Protection Centre, the Women’s Union, the Department of Agriculture and Rural Development, the Provincial Centre for Rural Water Supply and Sanitation, the Committee for Ethnic Minorities, Department of Justice. Finalization and editing of the report was conducted by the UNICEF Viet Nam Country Office. -

Text Editing in UNIX: an Introduction to Vi and Editing

Text Editing in UNIX A short introduction to vi, pico, and gedit Copyright 20062009 Stewart Weiss About UNIX editors There are two types of text editors in UNIX: those that run in terminal windows, called text mode editors, and those that are graphical, with menus and mouse pointers. The latter require a windowing system, usually X Windows, to run. If you are remotely logged into UNIX, say through SSH, then you should use a text mode editor. It is possible to use a graphical editor, but it will be much slower to use. I will explain more about that later. 2 CSci 132 Practical UNIX with Perl Text mode editors The three text mode editors of choice in UNIX are vi, emacs, and pico (really nano, to be explained later.) vi is the original editor; it is very fast, easy to use, and available on virtually every UNIX system. The vi commands are the same as those of the sed filter as well as several other common UNIX tools. emacs is a very powerful editor, but it takes more effort to learn how to use it. pico is the easiest editor to learn, and the least powerful. pico was part of the Pine email client; nano is a clone of pico. 3 CSci 132 Practical UNIX with Perl What these slides contain These slides concentrate on vi because it is very fast and always available. Although the set of commands is very cryptic, by learning a small subset of the commands, you can edit text very quickly. What follows is an outline of the basic concepts that define vi. -

AIX Globalization

AIX Version 7.1 AIX globalization IBM Note Before using this information and the product it supports, read the information in “Notices” on page 233 . This edition applies to AIX Version 7.1 and to all subsequent releases and modifications until otherwise indicated in new editions. © Copyright International Business Machines Corporation 2010, 2018. US Government Users Restricted Rights – Use, duplication or disclosure restricted by GSA ADP Schedule Contract with IBM Corp. Contents About this document............................................................................................vii Highlighting.................................................................................................................................................vii Case-sensitivity in AIX................................................................................................................................vii ISO 9000.....................................................................................................................................................vii AIX globalization...................................................................................................1 What's new...................................................................................................................................................1 Separation of messages from programs..................................................................................................... 1 Conversion between code sets............................................................................................................. -

Course Bidding at Business Schools

Course Bidding at Business Schools Authors: Tayfun Sönmez, M. Ünver This work is posted on eScholarship@BC, Boston College University Libraries. Boston College Working Papers in Economics, 2005 Originally posted on: http://ideas.repec.org/p/boc/bocoec/618.html Course Bidding at Business Schools∗ Tayfun S¨onmez Ko¸cUniversity and M. Utku Unver¨ Ko¸cUniversity Abstract Mechanisms that rely on course bidding are widely used at Business Schools in order to allocate seats at oversubscribed courses. Bids play two key roles under these mechanisms: Bids are used to infer student preferences and bids are used to determine who have bigger claims on course seats. We show that these two roles may easily conßict and preferences induced from bids may signiÞcantly differ from the true preferences. Therefore while these mechanisms are promoted as market mechanisms, they do not necessarily yield market out- comes. The two conßicting roles of bids is a potential source of efficiency loss part of which can be avoided simply by asking students to state their preferences in addition to bidding and thus “separating” the two roles of the bids. While there may be multiple market outcomes under this proposal, there is a market outcome which Pareto dominates any other market outcome. ∗We would like to thank seminar participants at London Business School and SITE 2003 Workshop on Matching Markets for their insightful comments. S¨onmez gratefully acknowledges the research support of Ko¸cBank via the Ko¸cBank scholar program and Turkish Academy of Sciences in the framework of the Young Scientist Award Program via grant TS/TUBA-GEB¨ IP/2002-1-19.ú Any errors are our own responsibility. -

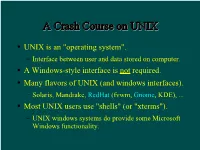

A Crash Course on UNIX

AA CCrraasshh CCoouurrssee oonn UUNNIIXX UNIX is an "operating system". Interface between user and data stored on computer. A Windows-style interface is not required. Many flavors of UNIX (and windows interfaces). Solaris, Mandrake, RedHat (fvwm, Gnome, KDE), ... Most UNIX users use "shells" (or "xterms"). UNIX windows systems do provide some Microsoft Windows functionality. TThhee SShheellll A shell is a command-line interface to UNIX. Also many flavors, e.g. sh, bash, csh, tcsh. The shell provides commands and functionality beyond the basic UNIX tools. E.g., wildcards, shell variables, loop control, etc. For this tutorial, examples use tcsh in RedHat Linux running Gnome. Differences are minor for the most part... BBaassiicc CCoommmmaannddss You need these to survive: ls, cd, cp, mkdir, mv. Typically these are UNIX (not shell) commands. They are actually programs that someone has written. Most commands such as these accept (or require) "arguments". E.g. ls -a [show all files, incl. "dot files"] mkdir ASTR688 [create a directory] cp myfile backup [copy a file] See the handout for a list of more commands. AA WWoorrdd AAbboouutt DDiirreeccttoorriieess Use cd to change directories. By default you start in your home directory. E.g. /home/dcr Handy abbreviations: Home directory: ~ Someone else's home directory: ~user Current directory: . Parent directory: .. SShhoorrttccuuttss To return to your home directory: cd To return to the previous directory: cd - In tcsh, with filename completion (on by default): Press TAB to complete filenames as you type. Press Ctrl-D to print a list of filenames matching what you have typed so far. Completion works with commands and variables too! Use ↑, ↓, Ctrl-A, & Ctrl-E to edit previous lines. -

Decision No. 5811QD-Ttg of April 20, 2011, Approving the Master Plan On

Issue nos 04-06/Mtly2011 67 (Cong BaG nos 233-234IAprrI30, 2011) Decision No. 5811QD-TTg of April 20, lifting Kon Tum province from the poverty 2011, approving the master plan on status. socio-economic development of Kon 3. To incrementally complete infrastructure Turn province through 2020 and urbanization: to step up the development of a number of economic zones as a motive force for hoosting the development of difficulty-hit THE PRIME MINISTER areas in the province. Pu rsriant to the Dcccml.cr 25, 2001 Law 011 4. 10 achieve social progress and justice in Organization ofthe Government; each step of development. To pay attention to Pursuant to the Government :\' Decree No 92/ supporti ng deep-lying. remote and ethnic 2006/NDCP of September 7, 2006, Oil the minority areas in comprehensive development; formulatiou, approval and II1(1fWgClIlCllt of to conserve and bring into play the traditional socio-economic del'elopmem master plans and cultures ofethnic groups. Decree No. 04/2008/ND-CP of Januarv 11, 5. To combine socio-economic development 2008, amending and supplementing a number with defense and security maintenance; to firmly ofarticles ofDecree No. 92/2006/ND-C/': defend the national border sovereignty; to firmly At the proposal (if the PeOIJ! e's Committee maintain pol itical security and social order and ofKon Tum province, safety; 10 enhance friendly and cooperative relations within the Vietnam- Laos- Cambodia DECIDES: development triangle. Article I. To approve the master plan on II. DEVELOPMENT OBJECTIVES soc io-ccrmomic rl('v~lnpnH'nt of Kon Tum province through 2010, with the following I. -

Applying a Coupled Nature–Human Flood Risk Assessment Framework in a Case for Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam

water Article Climate Justice Planning in Global South: Applying a Coupled Nature–Human Flood Risk Assessment Framework in a Case for Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam Chen-Fa Wu 1 , Szu-Hung Chen 2, Ching-Wen Cheng 3 and Luu Van Thong Trac 1,* 1 Department of Horticulture, National Chung Hsing University, Taichung City 402, Taiwan; [email protected] 2 International Master Program of Agriculture, National Chung Hsing University, Taichung City 402, Taiwan; [email protected] 3 The Design School, Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ 85287, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +886-4-2285-9125 Abstract: Developing countries in the global south that contribute less to climate change have suffered greater from its impacts, such as extreme climatic events and disasters compared to developed countries, causing climate justice concerns globally. Ho Chi Minh City has experienced increased intensity and frequency of climate change-induced urban floods, causing socio-economic damage that disturbs their livelihoods while urban populations continue to grow. This study aims to establish a citywide flood risk map to inform risk management in the city and address climate justice locally. This study applied a flood risk assessment framework integrating a coupled nature–human approach and examined the spatial distribution of urban flood hazard and urban flood vulnerability. A flood hazard map was generated using selected morphological and hydro-meteorological indicators. A flood Citation: Wu, C.-F.; Chen, S.-H.; vulnerability map was generated based on a literature review and a social survey weighed by experts’ Cheng, C.-W.; Trac, L.V.T. -

PLEIKU, KONTUM and BAN ME THUOT Adventure

PT -CH03 PLEIKU, KONTUM and BAN ME THUOT adventure This 4-Days 3-Nights trip takes you in the Central Highlands and is made for those looking adventures or wanting to learn cultural life of ethnic groups in Vietnam as well as their festivities. Starting from Ho Chi Minh city, you then follow the infamous Ho Chi Minh Trail through the ethnic villages of the central highlands around Pleiku, Kon Tum and Buon Ma Thuot. Day 1: HO CHI MINH/ PLEIKU/ KONTUM/ PLEIKU (L, D) AM: Meet at Tan Son Nhat airport and check in procedure for Pleiku. Arrival and welcome by local guide. Route to Kontum. En route, visit Pleiphum village, home of Jarai ethnicity. Continue to Kontum. Lunch. PM: Kontum visits: Wooden Church, Catholic Seminary, a colonial-style building, housing Kontum diocese and a small exhibition pavilion describing the development of the Catholic community, as well as numberless artefacts related to daily lives of the local ethnicities in the region, Konkotu village, home of Bahnar group. Route back to Pleiku. Dinner & O/N in Pleiku. Day 2: PLEIKU/ BAN METHUOT (B,L,D) AM: Visit T’Nung Lake, then Depart for Ban Me Thuot. Lunch upon arrival. PM: Ba Me Thuot visits: AkoDong village, where you can get immersed in Edeh culture, Local highland ethnicities museum displaying a wide range of Central Highland culture, clothing, local activities..., Dray Sap Waterfalls. Back to hotel. Dinner & O/N in Ban Me Thuot. Day 3: BAN ME THUOT/ LAK Lake/ BAN ME THUOT (B,L,D) Transfer to Lak lake, visit Jun village, home of Mnong ethnic people. -

Introduction to Unix Shell (Part I)

Introduction to Unix shell (part I) Evgeny Stambulchik Faculty of Physics, Weizmann Institute of Science, Rehovot 7610001, Israel Joint ICTP-IAEA School on Atomic Processes in Plasmas February 27 – March 3, 2017 Trieste, Italy Contrary to popular belief, Unix is user friendly. It just happens to be very selective about who it decides to make friends with. Unknown Initially used at Bell Labs, but soon licensed to academy (notably, U. of California, Berkeley) and commercial vendors (IBM, Sun, etc). There are two major products that came out of Berkeley: LSD and Unix. We don’t believe this to be a coincidence. Jeremy S. Anderson, Unix systems administrator Historical overview (kind of) Unix is a family of multiuser, multitasking operating systems stemming from the original Unix developed in the 1970’s at Bell Labs by Ken Thompson, Dennis Ritchie1, and others. Some consider Unix to be the second most important invention to come out of AT&T Bell Labs after the transistor. Dennis Ritchie 1Also famous for creating the C programming language. Historical overview (kind of) Unix is a family of multiuser, multitasking operating systems stemming from the original Unix developed in the 1970’s at Bell Labs by Ken Thompson, Dennis Ritchie1, and others. Some consider Unix to be the second most important invention to come out of AT&T Bell Labs after the transistor. Dennis Ritchie Initially used at Bell Labs, but soon licensed to academy (notably, U. of California, Berkeley) and commercial vendors (IBM, Sun, etc). There are two major products that came out of Berkeley: LSD and Unix. -

Measuring Indicators for Landscape Change in Kon Tum Province, Vietnam

Modern Environmental Science and Engineering (ISSN 2333-2581) November 2019, Volume 5, No. 11, pp. 1009-1019 Doi: 10.15341/mese(2333-2581)/11.05.2019/004 Academic Star Publishing Company, 2019 www.academicstar.us Measuring Indicators for Landscape Change in Kon Tum Province, Vietnam Lai Vinh Cam, Nguyen Van Hong, Vuong Hong Nhat, Nguyen Thi Thu Hien, Nguyen Phuong Thao, Tran Thi Nhung, and Le Ba Bien Institute of Geography, Vietnam Academy of Science and Technology, Vietnam Abstract: This paper’s aim is concentrated on measuring the difference in landscape visual character as an indicator of landscape change. Seven landscape character indicators are used for calculating in a study area in Kon Tum province, Vietnam; concluding Landscape Shape Index, Aggregation Index, Number of Patches, Patch Density, Patch Cohesion Index, Perimeter - Area Ratio, Percentage of Landscape. This set of indicators proposed in previous research by McGarigal and Marks (1995) and calculated with GIS, Fragstats software. These indicators also express the attributes of the component maps which we used for main input data are land-use map, digital elevation map and soil map. These are the necessary mapping materials for calculating the indicators. In the method is used in this paper, a value for each indicator will be assigned for each observation to capture the character of the landscape. They will be compared with each other and considered changes in the forest, agricultural, artificial and others. This work is replicable and transparent, and constitutes a methodological step for landscape indication, since it adds a reference value for analyzing differences in landscape character.