H-Diplo Review Essay

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Parliamentary Voices on the Future of Europe

Parliamentary Voices on the Future of Europe Digital Conference 28 and 29 May 2019 https://www.regioparl.com/parliamentary-voices-on-the-future-of-europe/?lang=en Conference Report © Picture: European Parliament 1 Conference Report Parliamentary Voices on the Future of Europe Digital Conference, 28 & 29 May 2020 Governance in Europe is built on a diverse multi-level parliamentary system, making parliaments at all levels – European, national, and subnational – key actors in the functioning of any democratic political process involving the future of Europe. This is why parliaments took centre stage in the two-day digital conference, which brought together academics and policy makers from all political levels – European, national, and subnational – in order to encourage an exchange of views between politics and academia. The event touched upon various issues of parliamentary involvement in the European Union (EU), such as the democratic legitimacy of EU politics, parliamentary scrutiny of European policies and Europeanisation of national and subnational parliaments. Aiming at fostering a debate between research and politics, it brought together a number of outstanding experts from academia and politics, who contributed to very insightful and lively debates on (1) the current state of play of parliamentary voices in the EU and (2) opportunities and obstacles for a strengthening of parliamentary voices in the future of the EU, in general, and in the upcoming EU Conference on the Future of Europe to be kicked-off in autumn, in particular. This conference report presents a summary of the various programme points, including keynotes and Q&A sessions as well as panel discussions and roundtables. -

Programme of the Youth, Peace and Security Conference

1 Wednesday, 23 May European Parliament – open to all participants – 12:00 – 13:00 Registration European Parliament Accreditation Centre (right-hand side of the Simone Veil Agora entrance to the Altiero Spinelli building) 13:00 – 14:00 Buffet lunch reception Members’ Restaurant, Altiero Spinelli building 14:00 – 15:00 Opening Session Room 5G-3, Altiero Spinelli building Keynote Address by Mr. Antonio Tajani, President of the European Parliament Chair Ms. Heidi Hautala, Vice-President of the European Parliament Speakers Ms. Mariya Gabriel, EU Commissioner for Digital Economy and Society Mr. Oscar Fernandez-Taranco, UN Assistant Secretary-General for Peacebuilding Support Ms. Ivana Tufegdzic, fYROM, EP Young Political Leaders Mr. Dereje Wordofa, UNFPA Deputy Executive Director Ms. Nour Kaabi, Tunisia, NET-MED Youth – UNESCO Mr. Oyewole Simon Oginni, Nigeria, Former AU-EU Youth Fellow 2 15:00 – 16:30 Parallel Thematic Panel Discussions Panel I Youth inclusion for conflict prevention and sustaining peace Library reading room, Altiero Spinelli building Discussants Ms. Soraya Post, Member of the European Parliament Mr. Oscar Fernandez-Taranco, UN Assistant Secretary-General for Peacebuilding Support Mr. Christian Leffler, Deputy Secretary-General, European External Action Service Mr. Amnon Morag, Israel, EP Young Political Leaders Ms. Hela Slim, France, Former AU-EU Youth Fellow Mr. MacDonald K. Munyoro, Zimbabwe, EP Young Political Leaders Facilitator Ms. Gizem Kilinc, United Network of Young Peacebuilders Panel II Young people innovating for peace Library room 128, Altiero Spinelli building Discussants Ms. Barbara Pesce-Monteiro, Director, UN/UNDP Representation Office in Brussels Ms. Anna-Katharina Deininger, OSCE CiO Special Representative and OSG Focal Point on Youth and Security Ms. -

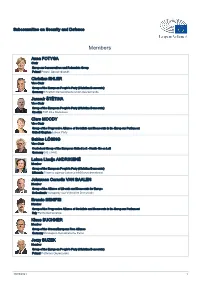

List of Members

Subcommittee on Security and Defence Members Anna FOTYGA Chair European Conservatives and Reformists Group Poland Prawo i Sprawiedliwość Christian EHLER Vice-Chair Group of the European People's Party (Christian Democrats) Germany Christlich Demokratische Union Deutschlands Jaromír ŠTĚTINA Vice-Chair Group of the European People's Party (Christian Democrats) Czechia TOP 09 a Starostové Clare MOODY Vice-Chair Group of the Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats in the European Parliament United Kingdom Labour Party Sabine LÖSING Vice-Chair Confederal Group of the European United Left - Nordic Green Left Germany DIE LINKE. Laima Liucija ANDRIKIENĖ Member Group of the European People's Party (Christian Democrats) Lithuania Tėvynės sąjunga-Lietuvos krikščionys demokratai Johannes Cornelis VAN BAALEN Member Group of the Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe Netherlands Volkspartij voor Vrijheid en Democratie Brando BENIFEI Member Group of the Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats in the European Parliament Italy Partito Democratico Klaus BUCHNER Member Group of the Greens/European Free Alliance Germany Ökologisch-Demokratische Partei Jerzy BUZEK Member Group of the European People's Party (Christian Democrats) Poland Platforma Obywatelska 30/09/2021 1 Aymeric CHAUPRADE Member Europe of Freedom and Direct Democracy Group France Les Français Libres Javier COUSO PERMUY Member Confederal Group of the European United Left - Nordic Green Left Spain Independiente Arnaud DANJEAN Member Group of the European People's Party -

Ipi Congress Report 2

SALZBURG IPI CONGRESS REPORT 2www.freemedia.at003 IPI WORLD CONGRESS & 52nd GENERAL ASSEMBLY IPI Congress Report CONTENTS Programme ................................................ 1 Editorial........................................................ 4 Opening Ceremony .............................. 6 Pluralism, Democracy and the Clash of Civilisations ................14 INTERNATIONAL Analysing the World Summit PRESS INSTITUTE on the Information Society............ 24 Chairman SARS and the Media ........................ 30 Jorge E. Fascetto Chairman of the Board, Diario el Día La Plata, Argentina IPI Free Media Pioneer 2003 ...... 38 Director Congress Snapshots ........................ 40 Johann P. Fritz Media in War Zones Congress Coordinator and and Regions of Conflict .................. 42 Editor, IPI Congress Report Michael Kudlak The International News Safety Institute........................ 52 Assistant Congress Coordinator Christiane Klint Media Self-Regulation: A Press Freedom Issue .................. 56 Congress Transcripts Rita Klint The Transatlantic Rift ........................ 64 International Press Institute (IPI) The Oslo Accords Spiegelgasse 2/29, A-1010 Vienna, Austria – 10 Years On........................................ 74 Tel: +43-1-512 90 11, Fax: +43-1-512 90 14 E-mail: [email protected], http://www.freemedia.at Farewell Remarks................................ 77 Cover Photograph: Tourismus Salzburg GmbH • Layout: Nik Bauer Printing kindly sponsored by Heidelberger Druckmaschinen Osteuropa Vertriebs-GmbH Paper kindly -

EP Elections 2014

EP Elections 2014 Biographies of new MEPs Please find the biographies of all the new MEPs elected to the 8th European Parliamentary term. The information has been collated from published sources and, in many cases, subject to translation from the native language. We will be contacting all MEPs to add to their biographical information over the summer, which will all be available on Dods People EU in due course. EU Elections 2014 Source: European Parliament- 1 - EP Overview (13/06/2014) List of countries: Austria Germany Poland Belgium Greece Portugal Bulgaria Hungary Romania Croatia Ireland Slovakia Cyprus Italy Slovenia Czech Latvia Spain Republic Denmark Lithuania Sweden United Estonia Luxembourg Kingdom Finland Malta France Netherlands EU Elections 2014 - 2 - Austria o People's Party (ÖVP) > EPP o Social Democratic Party (SPÖ) > S&D o Freedom Party (FPÖ) > NI o The Greens (GRÜNE) > Greens/EFA o New Austria (NEOS) > ALDE People’s Party (ÖVP) Claudia Schmidt (ÖVP, Austria) 26 April 1963 (FEMALE) Political: Councils/Public Bodies Member, Municipal Council, City of Salzburg 1999-; Chair, Austrian People's Party (ÖVP) Parliamentary Group, Salzburg Municipal Council 2004-09; Member, responsible for construction and urban development, Salzburg city government, 2009- Party posts: ÖVP: Vice-President, Salzburg, Member of the Board, Salzburg, Political Interest: Disability (social affairs) Personal: Non-political Career: Disability support institution (Lebenshilfe) Salzburg: Manager for special needs education 1989-1996, Officer responsible for -

1 03 Sept. 2014 How the Sakharov Prize 2014 Is Awarded Background Briefing in the Next 10 Days, the Nominations of the Sakharov

1 03 Sept. 2014 How the Sakharov Prize 2014 is awarded Background briefing In the next 10 days, the nominations of the Sakharov Prize for Human Rights will be decided by the European Parliament. The prize is awarded to “honour exceptional individuals who combat intolerance, fanaticism and oppression.”1 Previous winners include Nelson Mandela, Reporters without Borders and Anatoli Marchenko. If you believe that Azerbaijani human rights defenders – who are now in jail following years of work on behalf of the rights of others, and most recently on a list of political prisoners in Azerbaijan (on which they are now included) – then let the MEPs who vote on this know. Nominations for the Sakharov Prize can be made by: Political groups in the European Parliament. Or At least 40 MEPs. The deadline for nominations is Thursday 18 September at 12:00 in Strasbourg. NOTE: In order to decide on a nominee from their group some political groups have internal deadlines in the course of the next week. The next days are crucial. We focus here on four important political groups which might to support this nomination: The EPP Social Democrats Liberals Greens 1Source: The European Union website: http://www.europarl.europa.eu/aboutparliament/en/00f3dd2249/Sakharov-Prize-for-Freedom-of-Thought.html 2 Once the nominations are been made, the Foreign Affairs and Development committees vote on a shortlist of three finalists. This happens on either Monday 6th or Tuesday 7th October 2014. The members list for the foreign affairs committee can be found here: http://www.europarl.europa.eu/committees/en/afet/members.html, while the development committee is here: http://www.europarl.europa.eu/committees/en/deve/members.html#menuzone. -

Distribution Agreement in Presenting This Thesis As a Partial Fulfillment Of

Distribution Agreement In presenting this thesis as a partial fulfillment of the requirements for a degree from Emory University, I hereby grant to Emory University and its agents the non-exclusive license to archive, make accessible, and display my thesis in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter now, including display on the World Wide Web. I understand that I may select some access restrictions as part of the online submission of this thesis. I retain all ownership rights to the copyright of the thesis. I also retain the right to use in future works (such as articles or books) all or part of this thesis. Paul David Greenstein April 5, 2019 The Rise of and Literary Response to the New Far Right in Austria and Germany By Paul David Greenstein Prof. Paul Buchholz Adviser Department of German Studies Prof. Paul Buchholz Adviser Prof. Peter Höyng Committee Member Prof. Jason Morgan Ward Committee Member (if you have more than three committee members, add lines for them) 2019 The Rise of and Literary Response to the New Far Right in Austria and Germany By Paul David Greenstein Prof. Paul Buchholz Adviser An abstract of a thesis submitted to the Faculty of Emory College of Arts and Sciences of Emory University in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Bachelor of Sciences with Honors Department of German Studies 2019 Abstract The Rise of and Literary Response to the New Far Right in Austria and Germany By Paul David Greenstein The Austrian Freedom Party, once a marginal force in politics, experienced a meteoric electoral rise between 1986 and 2000 under the leadership of Jörg Haider; this was accompanied by a simultaneous, and drastic, shift of that party to the right. -

Austria͛s Internaional Posiion After the End Of

ƵƐƚƌŝĂ͛Ɛ/ŶƚĞƌŶĂƟŽŶĂůWŽƐŝƟŽŶ ĂŌĞƌƚŚĞŶĚŽĨƚŚĞŽůĚtĂƌ Günter Bischof, Ferdinand Karlhofer (Eds.) CONTEMPORARY AUSTRIAN STUDIES | VOLUME 22 UNO PRESS innsbruck university press Copyright © 2013 by University of New Orleans Press, New Orleans, Louisiana, USA All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form, or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage nd retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. All inquiries should be addressed to UNO Press, University of New Orleans, LA 138, 2000 Lakeshore Drive. New Orleans, LA, 70119, USA. www.unopress.org. Printed in the United States of America Design by Lauren Capone Cover photo credit: Hopi Media Published in the United States by Published and distributed in Europe University of New Orleans Press: by Innsbruck University Press ISBN: 9781608011162 ISBN: 9783902936011 UNO PRESS Contemporary Austrian Studies Sponsored by the University of New Orleans and Universität Innsbruck Editors Günter Bischof, CenterAustria, University of New Orleans Ferdinand Karlhofer, Universität Innsbruck Assistant Editor Production and Copy Editor Dominik Hofmann-Wellenhof Lauren Capone University of New Orleans Executive Editors Christina Antenhofer, Universität Innsbruck Kevin Graves, University of New Orleans Advisory Board Siegfried Beer Sándor Kurtán Universität Graz Corvinus University Budapest Peter Berger Günther Pallaver Wirtschaftsuniversität -

Asamblea General Distr

Naciones Unidas A/HRC/24/G/3 Asamblea General Distr. general 10 de septiembre de 2013 Español Original: inglés Consejo de Derechos Humanos 24º período de sesiones Tema 8 de la agenda Seguimiento y aplicación de la Declaración y el Programa de Acción de Viena Nota verbal de fecha 4 de septiembre de 2013 dirigida a la Oficina del Alto Comisionado de las Naciones Unidas para los Derechos Humanos por la Misión Permanente de Austria ante la Oficina de las Naciones Unidas en Ginebra La Misión Permanente de Austria en Ginebra saluda atentamente a la Secretaría del Consejo de Derechos Humanos y tiene el honor de adjuntar el informe de la conferencia internacional de expertos titulada "Vienna+20: advancing the protection of human rights – achievements, challenges and perspectives – 20 years after the World Conference" (Viena+20 – Promoción de la protección de los derechos humanos: logros, desafíos y perspectivas 20 años después de la Conferencia Mundial). La Misión Permanente de Austria pide a la Secretaría del Consejo de Derechos Humanos que tenga a bien distribuir la presente nota verbal y su anexo* como documento del 24º período de sesiones del Consejo de Derechos Humanos en relación con el tema 8 de la agenda. * Se distribuye tal como se recibió, en el idioma en que se presentó únicamente. GE.13-16910 (S) 200913 300913 A/HRC/24/G/3 Anexo [Inglés únicamente] Vienna +20: ADVANCING THE PROTECTION OF HUMAN RIGHTS, Achievements, Challenges and Perspectives 20 Years after the World Conference, International Expert Conference, Vienna Hofburg, 27-28 June 2013, CONFERENCE REPORT On the occasion of the 20th anniversary of the Vienna World Conference on Human Rights, Austria, in cooperation with the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, organised an international expert conference entitled „Vienna+20: Advancing the Protection of Human Rights“ on 27 and 28 June 2013 in Vienna. -

Delivering Empowered Welfare Societies

Delivering Empowered Welfare Societies With foreword by: Alfred GUSENBAUER Edited by: Ernst STETTER Karl DUFFEK Ania SKRZYPEK TAKING THE LEAD: SEIZING THE INDEX MOMENT, TAKING RESPONSIBILITY AND DEVISING A NEW SOCIAL COMPACT FRAMING A NEW PROGRESSIVE 145 Rethinking the European Social NARRATIVE Model 6 Introduction Dimitris TSAROUHAS Ernst STETTER, Karl DUFFEK 166 A Social Compact for a Social & Ania SKRZYPEK Union: A Political and Legal 15 How the Things Unfold... Window of Opportunity? Alfred GUSENBAUER Steven VAN HECKE, Johan LIEVENS & Gilles PITTOORS FOCUSING THE AGENDA: EQUALITY, QUALITY EMPLOYMENT 184 Socio-Economic Policy AND DECENT LIVING STANDARDS Making and the Contemporary Prospects for a ‘Social Europe’ 28 Wage, Employment, Working Alternative Conditions and Productivity: David J. BAILEY A New Focus on Quality Rémi BAZILLIER 202 Delivering Public Welfare Services in the Europe of 52 The Economic and Austerity. Responsibility vs Social Consequences Responsiveness? of the Obsession with Amandine CRESPY Competitiveness in the EMU Ronny MAZOCCHI 228 “Daring More Democracy” – Refl ections on the Future 72 Public Investments… To Do Foundation of Welfare Society What? Beyond ‘Bread and Pascal ZWICKY Butter’ Social Democracy Carlo D’IPPOLITI ACTING THROUGH EUROPE: SOLIDARITY, POLITICIZATION AND 90 The Politics of Productivity: COMMUNITARIAN METHOD Big Data Management and the Meaning of Work in the Post 258 External and Internal Crisis EU Challenges to Social Michael WEATHERBURN Democratic Leadership in Europe 110 Gender Equality: judicial -

Useful Idiots' in the West: an Overview of RT's Editorial Strategy and Evidence of Impact

Kremlin Watch Report 10.09.2017 The Kremlin's Platform for 'Useful Idiots' in the West: An Overview of RT's Editorial Strategy and Evidence of Impact Kremlin Watch is a strategic program which Monika L. Richter Kremlin Watch is a strategic program, which aims aimsto expose to expose and confrontand confront instruments instruments of Russian of Kremlin Watch Program Analyst Russianinfluence andinfluence disinformation and operationsdisinformation focused operations focusedagainst Westernagainst democracies.Western democracies. The Kremlin's Platform for 'Useful Idiots' in the West: An Overview of RT's Editorial Strategy and Evidence of Impact Table of Contents 1. Executive summary ........................................................................................................................................................... 2 Key points ......................................................................................................................................................................... 3 2. Introduction ........................................................................................................................................................................ 6 3. Russia Today: Background and strategic objectives ......................................................................................................... 8 I. 2005 – 2008: A public diplomacy mandate .................................................................................................................... 8 II. 2008 – 2009: Reaction -

Volume 10 • Number 1 • June 2014 • ISSN 1801-3422 June 2014 • Number 1 •

POLITICS IN CENTRAL EUROPE The Journal of the Central European Political Science Association Volume 10 • Number 1 • June 2014 • ISSN 1801-3422 June 2014 • Number 1 • Volume 10 Volume Responses on the Crisis ESSAYS The Long ‑lasting Effects of the Economic Crisis on Political Culture Toma Burean, Csongor‑Ernő Szőcs and Gabriel Badescu Neo ‑liberal, Neo ‑Keynasian or Just Standard response on the Crisis? Clash of Ideologies in Czech Political, scientific and Public Debate POLITICS IN CENTRAL IN POLITICS EUROPE Ladislav Cabada Ideological Profile and Crisis Discourse of Slovenian Elites Matevž Tomšič and Lea Prijon Austria and its Experience with European Parliament Elections: Evidence since 1996 Sylvia Kritzinger and Karin Liebhart BOOK REVIEWS POLITICS in Central Europe The Journal of the Central European Political Science Association Volume 10 Number 1 June 2014 ISSN 1801-3422 Responses on the Crisis ESSAYS The Long ‑lasting Effects of the Economic Crisis on Political Culture Toma Burean, Csongor‑Ernő Szőcs and Gabriel Badescu Neo ‑liberal, Neo ‑Keynasian or Just Standard response on the Crisis? Clash of Ideologies in Czech Political, scientific and Public Debate Ladislav Cabada Ideological Profile and Crisis Discourse of Slovenian Elites Matevž Tomšič and Lea Prijon Austria and its Experience with European Parliament Elections: Evidence since 1996 Sylvia Kritzinger and Karin Liebhart BOOK REVIEWS Politics in Central Europe – The Journal of Central European Political Science Association is the official Journal of the Central European Political Science Association (CEPSA). Politics in Central Europe is a biannual (June and December), double‑blind, peer‑reviewed publication. Publisher: Metropolitan University Prague Press Dubečská 900/10, 100 31 Praha 10-Strašnice (Czech Republic) Printed by: Togga, s.