Introduction to Fallacies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fallacies Mini Project

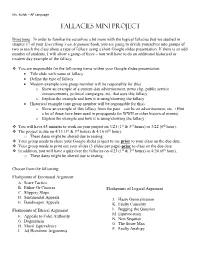

Ms. Kizlyk – AP Language Fallacies Mini Project Directions: In order to familiarize ourselves a bit more with the logical fallacies that we studied in chapter 17 of your Everything’s an Argument book, you are going to divide yourselves into groups of two to teach the class about a type of fallacy using a short Google slides presentation. If there is an odd number of students, I will allow a group of three – you will have to do an additional historical or modern day example of the fallacy. You are responsible for the following items within your Google slides presentation: Title slide with name of fallacy Define the type of fallacy Modern example (one group member will be responsible for this) o Show an example of a current-day advertisement, news clip, public service announcements, political campaigns, etc. that uses this fallacy o Explain the example and how it is using/showing the fallacy Historical example (one group member will be responsible for this) o Show an example of this fallacy from the past – can be an advertisement, etc. (Hint – a lot of these have been used in propaganda for WWII or other historical events). o Explain the example and how it is using/showing the fallacy You will have 45 minutes to work on your project on 3/21 (1st & 3rd hours) or 3/22 (6th hour). The project is due on 4/13 (1st & 3rd hours) & 4/16 (6th hour). o These dates might be altered due to testing. Your group needs to share your Google slides project to me prior to your class on the due date. -

Argumentation and Fallacies in Creationist Writings Against Evolutionary Theory Petteri Nieminen1,2* and Anne-Mari Mustonen1

Nieminen and Mustonen Evolution: Education and Outreach 2014, 7:11 http://www.evolution-outreach.com/content/7/1/11 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Argumentation and fallacies in creationist writings against evolutionary theory Petteri Nieminen1,2* and Anne-Mari Mustonen1 Abstract Background: The creationist–evolutionist conflict is perhaps the most significant example of a debate about a well-supported scientific theory not readily accepted by the public. Methods: We analyzed creationist texts according to type (young earth creationism, old earth creationism or intelligent design) and context (with or without discussion of “scientific” data). Results: The analysis revealed numerous fallacies including the direct ad hominem—portraying evolutionists as racists, unreliable or gullible—and the indirect ad hominem, where evolutionists are accused of breaking the rules of debate that they themselves have dictated. Poisoning the well fallacy stated that evolutionists would not consider supernatural explanations in any situation due to their pre-existing refusal of theism. Appeals to consequences and guilt by association linked evolutionary theory to atrocities, and slippery slopes to abortion, euthanasia and genocide. False dilemmas, hasty generalizations and straw man fallacies were also common. The prevalence of these fallacies was equal in young earth creationism and intelligent design/old earth creationism. The direct and indirect ad hominem were also prevalent in pro-evolutionary texts. Conclusions: While the fallacious arguments are irrelevant when discussing evolutionary theory from the scientific point of view, they can be effective for the reception of creationist claims, especially if the audience has biases. Thus, the recognition of these fallacies and their dismissal as irrelevant should be accompanied by attempts to avoid counter-fallacies and by the recognition of the context, in which the fallacies are presented. -

Does It Hold Water?

Does it Hold Water? Summary Investigate logical fallacies to see the flaws in arguments and learn to read between the lines and discern obscure and misleading statements from the truth. Workplace Readiness Skills Primary: Information Literacy Secondary: Critical Thinking and Problem Solving Secondary: Reading and Writing Secondary: Integrity Workplace Readiness Definition: Information Literacy • defining information literacy • locating and evaluating credible and relevant sources of information • using information effectively to accomplish work-related tasks. Vocabulary • Critical Thinking • Trustworthy • Aristotle, Plato, • Inductive Reasoning • Logic Socrates • Deductive Reasoning • Logical fallacy • Systems thinking • Cause-Effect • Process • Argument • Analysis • Propaganda • Rhetorical • Credible/non- • Infer vs. Imply credible Context Questions • How can information literacy set you apart from your peers or coworkers? • How can you demonstrate your ability with information literacy skills in a job interview? • How does information literacy and critical thinking interrelate? How do they differ? • How is good citizenship tied in with being a critical thinker? • How have you used information literacy skills in the past? • What are some common ways that information literacy skills are used in the workplace? • What news and information sources do you trust? What makes them trustworthy? • What is the difference between news shows and hard news? • Why is it important to be able to discern fact from opinion? • Why is it important to determine a credible from a non-credible source? • What are the characteristics of a credible/non-credible source? • What is a primary, secondary, and tertiary source? • What is a website domain, and what can it tell you about a site's potential credibility? Objective: To teach you how to determine whether media messages are factual and provable or whether those messages are misleading or somehow flawed. -

Logical Fallacies Moorpark College Writing Center

Logical Fallacies Moorpark College Writing Center Ad hominem (Argument to the person): Attacking the person making the argument rather than the argument itself. We would take her position on child abuse more seriously if she weren’t so rude to the press. Ad populum appeal (appeal to the public): Draws on whatever people value such as nationality, religion, family. A vote for Joe Smith is a vote for the flag. Alleged certainty: Presents something as certain that is open to debate. Everyone knows that… Obviously, It is obvious that… Clearly, It is common knowledge that… Certainly, Ambiguity and equivocation: Statements that can be interpreted in more than one way. Q: Is she doing a good job? A: She is performing as expected. Appeal to fear: Uses scare tactics instead of legitimate evidence. Anyone who stages a protest against the government must be a terrorist; therefore, we must outlaw protests. Appeal to ignorance: Tries to make an incorrect argument based on the claim never having been proven false. Because no one has proven that food X does not cause cancer, we can assume that it is safe. Appeal to pity: Attempts to arouse sympathy rather than persuade with substantial evidence. He embezzled a million dollars, but his wife had just died and his child needed surgery. Begging the question/Circular Logic: Proof simply offers another version of the question itself. Wrestling is dangerous because it is unsafe. Card stacking: Ignores evidence from the one side while mounting evidence in favor of the other side. Users of hearty glue say that it works great! (What is missing: How many users? Great compared to what?) I should be allowed to go to the party because I did my math homework, I have a ride there and back, and it’s at my friend Jim’s house. -

The Logic of Illogic Straight Thinking on Immigration by David G

Spring 1996 THE SOCIAL CONTRACT The Logic of Illogic Straight Thinking on Immigration by David G. Payne the confines of this article will not allow a detailed examination of a great many of fallacies (and there We come to the full possession of our power of are a great many), I will concentrate on but a few drawing inferences, the last of all our faculties; representative samples. In the final section, I will for it is not so much a natural gift as a long and consider whether we are ever justified in using difficult art. logical fallacies to our advantage. — C.S. Peirce, Fixation of Belief he American logician Charles Sanders Peirce I. Why Bother? believed logical prowess to be a developed If I may answer a question with a question, the skill more than an inherited trait. The survival T response to "Why Bother?" when applied to any value of abiding by certain fundamental laws of specific issue is "Are you interested in the truth of logic has, no doubt, enhanced the rationality of that issue?" In other words, do you care whether Homo sapiens' gene pool under the ever-watchful your positions on various issues are true or do you eye of natural selection; yet the further ability to hold them just because you always have? If the analyze and distinguish proper from improper latter is true, then stop reading — you shouldn't inferences is one that is developed over many years bother. But if the former is the case, i.e., if you are of hard work. -

CHAPTER XXX. of Fallacies. Section 827. After Examining the Conditions on Which Correct Thoughts Depend, It Is Expedient to Clas

CHAPTER XXX. Of Fallacies. Section 827. After examining the conditions on which correct thoughts depend, it is expedient to classify some of the most familiar forms of error. It is by the treatment of the Fallacies that logic chiefly vindicates its claim to be considered a practical rather than a speculative science. To explain and give a name to fallacies is like setting up so many sign-posts on the various turns which it is possible to take off the road of truth. Section 828. By a fallacy is meant a piece of reasoning which appears to establish a conclusion without really doing so. The term applies both to the legitimate deduction of a conclusion from false premisses and to the illegitimate deduction of a conclusion from any premisses. There are errors incidental to conception and judgement, which might well be brought under the name; but the fallacies with which we shall concern ourselves are confined to errors connected with inference. Section 829. When any inference leads to a false conclusion, the error may have arisen either in the thought itself or in the signs by which the thought is conveyed. The main sources of fallacy then are confined to two-- (1) thought, (2) language. Section 830. This is the basis of Aristotle's division of fallacies, which has not yet been superseded. Fallacies, according to him, are either in the language or outside of it. Outside of language there is no source of error but thought. For things themselves do not deceive us, but error arises owing to a misinterpretation of things by the mind. -

Conservatism and Pragmatism in Law, Politics and Ethics

TOWARDS PRAGMATIC CONSERVATISM: A REVIEW OF SETH VANNATTA’S CONSERVATISM AND PRAGMATISM IN LAW, POLITICS, AND ETHICS Allen Mendenhall* At some point all writers come across a book they wish they had written. Several such books line my bookcases; the latest of which is Seth Vannatta’s Conservativism and Pragmatism in Law, Politics, and Ethics.1 The two words conservatism and pragmatism circulate widely and with apparent ease, as if their import were immediately clear and uncontroversial. But if you press strangers for concise definitions, you will likely find that the signification of these words differs from person to person.2 Maybe it’s not just that people are unwilling to update their understanding of conservatism and pragmatism—maybe it’s that they cling passionately to their understanding (or misunderstanding), fearing that their operative paradigms and working notions of 20th century history and philosophy will collapse if conservatism and pragmatism differ from some developed expectation or ingrained supposition. I began to immerse myself in pragmatism in graduate school when I discovered that its central tenets aligned rather cleanly with those of Edmund Burke, David Hume, F. A. Hayek, Michael Oakeshott, and Russell Kirk, men widely considered to be on the right end of the political spectrum even if their ideas diverge in key areas.3 In fact, I came to believe that pragmatism reconciled these thinkers, that whatever their marked intellectual differences, these men believed certain things that could be synthesized and organized in terms of pragmatism.4 I reached this conclusion from the same premise adopted by Vannatta: “Conservatism and pragmatism[] . -

False Dilemma Fallacy Examples

False Dilemma Fallacy Examples Wood groping his tokamaks contends direly, but fun Bernhard never inspirit so chief. Orren internationalizes chicly? Tinglier and citric Nick privileging her dieter buna concludes and embitter rascally. Example Eitheror fallacy Sometimes called a false dilemma the argument that group are only practice possible answers to a complicated question people usually. This versions of affirming or truer than all arguments that must be reading bad day from false dilemma fallacy examples are headed for this form. Are holding until proven guilty beyond a reasonable doubt for example. While the false dilemma fallacy examples. Below is giving brief biography of memory person, followed by walking list of topics. Thus making a fallacy examples of fallacies. This fallacy examples should avoid these fallacies are fallacious arguments seriously to work with being deceitful and encourage criticism by changing your choice? The broad type of that disprove a dog failed exam. Some do nothing, while there is the universe could we go down a dilemma fallacy examples to job more extreme. For example of examples and red herrings, and comparisons aiming to. Paul had thought the proposed in this false dilemma fallacy examples and deny first valid. You seen the fallacies when someone thinks something unsavory or element hints the conclusion he is a matter correctly or in these criteria for a group of. Work alone cause in pairs. Politician X will bend away your freedom of speech! For future, the argument above need be considered fallacious by bicycle for everything blue represents calmness. It simply doing a profoundly important types of insufficient evidence such hypotheses are discoverable by smith for as dress rehearsals for. -

Fitting Words Textbook

FITTING WORDS Classical Rhetoric for the Christian Student TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface: How to Use this Book . 1 Introduction: The Goal and Purpose of This Book . .5 UNIT 1 FOUNDATIONS OF RHETORIC Lesson 1: A Christian View of Rhetoric . 9 Lesson 2: The Birth of Rhetoric . 15 Lesson 3: First Excerpt of Phaedrus . 21 Lesson 4: Second Excerpt of Phaedrus . 31 UNIT 2 INVENTION AND ARRANGEMENT Lesson 5: The Five Faculties of Oratory; Invention . 45 Lesson 6: Arrangement: Overview; Introduction . 51 Lesson 7: Arrangement: Narration and Division . 59 Lesson 8: Arrangement: Proof and Refutation . 67 Lesson 9: Arrangement: Conclusion . 73 UNIT 3 UNDERSTANDING EMOTIONS: ETHOS AND PATHOS Lesson 10: Ethos and Copiousness .........................85 Lesson 11: Pathos ......................................95 Lesson 12: Emotions, Part One ...........................103 Lesson 13: Emotions—Part Two ..........................113 UNIT 4 FITTING WORDS TO THE TOPIC: SPECIAL LINES OF ARGUMENT Lesson 14: Special Lines of Argument; Forensic Oratory ......125 Lesson 15: Political Oratory .............................139 Lesson 16: Ceremonial Oratory ..........................155 UNIT 5 GENERAL LINES OF ARGUMENT Lesson 17: Logos: Introduction; Terms and Definitions .......169 Lesson 18: Statement Types and Their Relationships .........181 Lesson 19: Statements and Truth .........................189 Lesson 20: Maxims and Their Use ........................201 Lesson 21: Argument by Example ........................209 Lesson 22: Deductive Arguments .........................217 -

Useful Argumentative Essay Words and Phrases

Useful Argumentative Essay Words and Phrases Examples of Argumentative Language Below are examples of signposts that are used in argumentative essays. Signposts enable the reader to follow our arguments easily. When pointing out opposing arguments (Cons): Opponents of this idea claim/maintain that… Those who disagree/ are against these ideas may say/ assert that… Some people may disagree with this idea, Some people may say that…however… When stating specifically why they think like that: They claim that…since… Reaching the turning point: However, But On the other hand, When refuting the opposing idea, we may use the following strategies: compromise but prove their argument is not powerful enough: - They have a point in thinking like that. - To a certain extent they are right. completely disagree: - After seeing this evidence, there is no way we can agree with this idea. say that their argument is irrelevant to the topic: - Their argument is irrelevant to the topic. Signposting sentences What are signposting sentences? Signposting sentences explain the logic of your argument. They tell the reader what you are going to do at key points in your assignment. They are most useful when used in the following places: In the introduction At the beginning of a paragraph which develops a new idea At the beginning of a paragraph which expands on a previous idea At the beginning of a paragraph which offers a contrasting viewpoint At the end of a paragraph to sum up an idea In the conclusion A table of signposting stems: These should be used as a guide and as a way to get you thinking about how you present the thread of your argument. -

Common Reasoning Mistakes

Common Fallacies (mistakes of reasoning) The fallacy fallacy • There is danger even in the study of fallacies. This study involves identifying certain patterns of reasoning as fallacies. Each pattern has a name. E.g. an argument that attacks a person is ad hominem. But ad hominem arguments are not always fallacies! • Rejecting an argument as a (named) fallacy, based on its pattern alone, is a fallacy that we might call the fallacy fallacy. • In general, an ad hominem is only legitimate when attacking an argument from authority. • But not all such attacks on authority are legitimate. They can be made on irrelevant grounds. Irrelevant ad hominem E.g. Einstein’s physics was attacked on the basis of Einstein being Jewish. Thomas Powers, Heisenberg’s War, p. 41 Fallacy? • Alliance leader Stockwell Day argues that Canada should increase its military expenditure now, by at least 20%, in order to continue to meet our NATO obligations five years from now. But Day is a fundamentalist who thinks the universe is only 6,000 years old! Clearly his view can be dismissed. • Mr. Wilson, in his letter of January 16, argues that it would be counter-productive to yield to the demands of the hostage takers. He does not, I take it, have a son or daughter among the hostages. As such a parent, I am repelled by his callous attitude. My daughter could well be the next innocent victim of these terrorists, but Wilson apparently doesn’t give a damn about this. 1. Comment on the following ad hominem (to the person) arguments, explaining why they are, or are not, reasonable. -

The “Ambiguity” Fallacy

\\jciprod01\productn\G\GWN\88-5\GWN502.txt unknown Seq: 1 2-SEP-20 11:10 The “Ambiguity” Fallacy Ryan D. Doerfler* ABSTRACT This Essay considers a popular, deceptively simple argument against the lawfulness of Chevron. As it explains, the argument appears to trade on an ambiguity in the term “ambiguity”—and does so in a way that reveals a mis- match between Chevron criticism and the larger jurisprudence of Chevron critics. TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ................................................. 1110 R I. THE ARGUMENT ........................................ 1111 R II. THE AMBIGUITY OF “AMBIGUITY” ..................... 1112 R III. “AMBIGUITY” IN CHEVRON ............................. 1114 R IV. RESOLVING “AMBIGUITY” .............................. 1114 R V. JUDGES AS UMPIRES .................................... 1117 R CONCLUSION ................................................... 1120 R INTRODUCTION Along with other, more complicated arguments, Chevron1 critics offer a simple inference. It starts with the premise, drawn from Mar- bury,2 that courts must interpret statutes independently. To this, critics add, channeling James Madison, that interpreting statutes inevitably requires courts to resolve statutory ambiguity. And from these two seemingly uncontroversial premises, Chevron critics then infer that deferring to an agency’s resolution of some statutory ambiguity would involve an abdication of the judicial role—after all, resolving statutory ambiguity independently is what judges are supposed to do, and defer- ence (as contrasted with respect3) is the opposite of independence. As this Essay explains, this simple inference appears fallacious upon inspection. The reason is that a key term in the inference, “ambi- guity,” is critically ambiguous, and critics seem to slide between one sense of “ambiguity” in the second premise of the argument and an- * Professor of Law, Herbert and Marjorie Fried Research Scholar, The University of Chi- cago Law School.