Tradition and Modernity in Discourses of Māori Urbanisation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Zealand Literature

ENGL331 New Zealand Literature Dylan Horrocks Hicksville, by permission Trimester 1, 2008 School of English, Film, Theatre & Media Studies 1 New Zealand Literature Class sessions Lecture: Monday, Friday 3.10pm – 4.00pm Hugh Mackenzie LT002 Weekly tutorials: Tutorials begin on 2 nd week of trimester; tutorial lists will be posted on the English noticeboard and on Blackboard. Each student attends eleven tutorials. Attendance at eight or more is required. The tutorials are a very important part of your development in the subject, and you should prepare fully for them by reading and being ready to contribute to the discussion. Course Organisation Convener: Mark Williams [email protected] 463 6810 (internal: 6810) office VZ 911 Lecturers: Mark Williams (MW) Jane Stafford (JS) [email protected] VZ905 Erin Mercer (EM) [email protected] VZ910 Hamish Clayton (HC) [email protected] Tutors: Tutors’ information will be posted on the Blackboard site. Blackboard • Updated information about the course, and all handouts etc relating to the course, are posted on the Blackboard site for this course. • Joining in the discussion about texts and issues on the class blackboard site is encouraged. • Access to the blackboard site is available through http://blackboard.vuw.ac.nz/ Aims, Objectives, Content The course is designed to expose you to a range of concepts relevant to more advanced students in literature; it will equip you with an understanding of the cultural and historical contexts of the material you are studying; and it will foster your ability to respond critically to a range of literary and theatrical texts and present your findings in formal assessment tasks. -

NEW ZEALAND ASIA INSTITUTE Te Roopu Aotearoa Ahia Annual

Level 4, 58 Symonds Street Private Bag 92019 Auckland, New Zealand Tel: (64 9) 373 7599 Fax: (64 9) 208 2312 Email: [email protected] NEW ZEALAND ASIA INSTITUTE Te Roopu Aotearoa Ahia Annual Report 2007 COMMITTED TO ASIAN KNOWLEDGE CREATION AND DISSEMINATIONAND BRIDGE-BUILDING AND NETWOEKING BETWEEN NEW ZEALAND AND ASIA CONTENTS Mission Statement 3 Acknowledgements 4 1. Overview of strategic and Institutional Development 5 2. Highlights of the Year 7 3. Program of Activities 11 4. NZAI Offshore 23 5. Financial Performance Reports 26 6. Staff Publications 28 7. Conclusion 30 Appendix 1 The NZAI Advisory Board, 2007 31 2 MISSION STATEMENT The mission of the Institute is to: o Initiate and develop a multidisciplinary research program addressing issues concerning Asia and New Zealand; o Provide a forum for discussion and debate on policy issues and disseminate the output from these activities; o Develop relationships with external constituencies in New Zealand and the Asian region; o Serve as the point of access by external constituencies to the University and to its expertise on Asia. 3 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The Institute acknowledges with gratitude the generous financial support from the Japan Foundation, the Academy of Koran Studies, the Asia-New Zealand Foundation, the Korean Foundation, and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade, without which the successful completion of research and policy briefing projects initiated by the Institute in 2007 would not have been possible. The Institute would also like to thank the following institutional -

Route N10 - City to Otara Via Manukau Rd, Onehunga, Mangere and Papatoetoe

ROUTE N10 - CITY TO OTARA VIA MANUKAU RD, ONEHUNGA, MANGERE AND PAPATOETOE Britomart t S Mission F t an t r t sh e S e S Bay St Marys aw Qua College lb n A y S e t A n Vector Okahu Bay St Heliers Vi e z ct t a o u T r S c Arena a Kelly ia Kohimarama Bay s m A S Q Tarltons W t e ak T v a e c i m ll e a Dr Beach es n ki le i D y S Albert r r t P M Park R Mission Bay i d a Auckland t Dr St Heliers d y D S aki r Tama ki o University y m e e Ta l r l l R a n Parnell l r a d D AUT t S t t S S s Myers n d P Ngap e n a ip Park e r i o Auckland Kohimarama n R u m e y d Domain d Q l hape R S R l ga d an R Kar n to d f a N10 r Auckland Hobson Bay G Hospital Orakei P Rid a d de rk Auckland ll R R R d d Museum l d l Kepa Rd R Glendowie e Orakei y College Grafton rn Selwyn a K a B 16 hyb P College rs Glendowie Eden er ie Pass d l Rd Grafton e R d e Terrace r R H Sho t i S d Baradene e R k h K College a Meadowbank rt hyb r No er P Newmarket O Orakei ew ass R Sacred N d We Heart Mt Eden Basin s t Newmarket T College y a Auckland a m w a ki Rd Grammar d a d Mercy o Meadowbank R r s Hospital B St Johns n Theological h o St John College J s R t R d S em Remuera Va u Glen ll d e ey G ra R R d r R Innes e d d St Johns u a Tamaki R a t 1 i College k S o e e u V u k a v lle n th A a ra y R R d s O ra M d e Rd e u Glen Innes i em l R l i Remuera G Pt England Mt Eden UOA Mt St John L College of a Auckland Education d t University s i e d Ak Normal Int Ea Tamaki s R Kohia School e Epsom M Campus S an n L o e i u n l t e e d h re Ascot Ba E e s Way l St Cuthberts -

Ōtara-Papatoetoe Area Plan December 2014 TABLE of CONTENTS TATAI KORERO

BC3685 THE OTARA-PAPATOETOE REA PLA MAHERE A ROHE O OTARA-PAPATOETOE DECEMBER 2014 HE MIHI Tēnā kia hoea e au taku waka mā ngā tai mihi o ata e uru ake ai au mā te awa o Tāmaki ki te ūnga o Tainui waka i Ōtāhuhu. I reira ka toia aku mihi ki te uru ki te Pūkaki-Tapu-a-Poutūkeka, i reira ko te Pā i Māngere. E hoe aku mihi mā te Mānukanuka a Hoturoa ki te kūrae o te Kūiti o Āwhitu. I kona ka rere taku haere mā te ākau ki te puaha o Waikato, te awa tukukiri o ngā tūpuna, Waikato Taniwharau, he piko he taniwha. Ka hīkoi anō aku mihi mā te taha whakararo mā Maioro ki Waiuku ki Mātukureira kei kona ko ngā Pā o Tahuna me Reretewhioi. Ka aro whakarunga au kia tau atu ki Pukekohe. Ka tahuri te haere a taku reo ki te ao o te tonga e whāriki atu rā mā runga i ngā hiwi, kia taka atu au ki Te Paina, ki te Pou o Mangatāwhiri. Mātika tonu aku mihi ki a koe Kaiaua te whākana atu rā ō whatu mā Tīkapa Moana ki te maunga tapu o Moehau. Ka kauhoetia e aku kōrero te moana ki Maraetai kia hoki ake au ki uta ki Ōhuiarangi, heteri mō Pakuranga. I reira ka hoki whakaroto ake anō au i te awa o Tāmaki ma te taha whakarunga ki te Puke o Taramainuku, kei konā ko Ōtara. Kātahi au ka toro atu ki te Manurewa a Tamapohore, kia whakatau aku mihi mutunga ki runga o Pukekiwiriki kei raro ko Papakura ki konā au ka whakatau. -

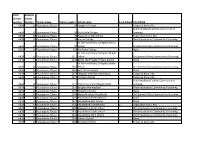

Cluster 10 Schools List

FIRST EDUMIS Cluster Cluster number Number Cluster Name School number School name Lead School COL NAME 6439 10 Papatoetoe /Otara 58 Tangaroa College Tangaroa Kahui Ako South Auckland Catholic Community of 6439 10 Papatoetoe /Otara 94 De La Salle College Learning 6439 10 Papatoetoe /Otara 95 Papatoetoe High School Papatoetoe Kahui Ako 6439 10 Papatoetoe /Otara 96 Aorere College West Papatoetoe Community of Learning Sir Edmund Hillary Collegiate Senior 6439 10 Papatoetoe /Otara 97 School Sir Edmund Hillary Community of Learning 6439 10 Papatoetoe /Otara 631 Kia Aroha College None Sir Edmund Hillary Collegiate Middle 6439 10 Papatoetoe /Otara 1217 School Sir Edmund Hillary Community of Learning 6439 10 Papatoetoe /Otara 1218 Bairds Mainfreight Primary School None Sir Edmund Hillary Collegiate Junior 6439 10 Papatoetoe /Otara 1251 School Sir Edmund Hillary Community of Learning 6439 10 Papatoetoe /Otara 1264 East Tamaki School None 6439 10 Papatoetoe /Otara 1274 Ferguson Intermediate (Otara) Tangaroa Kahui Ako 6439 10 Papatoetoe /Otara 1277 Flat Bush School Tangaroa Kahui Ako South Auckland Catholic Community of 6439 10 Papatoetoe /Otara 1315 Holy Cross School (Papatoetoe) Learning 6439 10 Papatoetoe /Otara 1329 Kedgley Intermediate West Papatoetoe Community of Learning 6439 10 Papatoetoe /Otara 1333 Kingsford School None 6439 10 Papatoetoe /Otara 1369 Mayfield School (Auckland) Sir Edmund Hillary Community of Learning 6439 10 Papatoetoe /Otara 1426 Papatoetoe Central School None 6439 10 Papatoetoe /Otara 1427 Papatoetoe East School None 6439 -

A Review on the Maori Research As the Unique Language

AD ALTA JOURNAL OF INTERDISCIPLINARY RESEARCH A REVIEW ON THE MAORI RESEARCH AS THE UNIQUE LANGUAGE AND CULTURAL IDENTITY OF NEW ZEALAND aANNA BEKEEVA, bELENA NOTINA, cIRINA BYKOVA, Adult learning programs such as Te Ataarangi and Wananga dVALENTINA ULIUMDZHIEVA Reo (immersion courses for adults) were also developed throughout the country with the result that the older generation People’s Friendship University of Russia – RUDN University, of fluent speakers is indeed disappearing. Today the amount of 8/2 Miklukho-Maklaya Street, Moscow 117198, Russia spoken Maori varies around the country, with considerably more email: [email protected], being heard in the North Island than in the South Island. The [email protected], [email protected], language is kept in the public awareness through radio and [email protected] television programs, together with bilingual road signs and lexical items such as marae (a meeting place), hui (a meeting), The publication has been prepared with the support of the «RUDN University Program kaupapa (an agenda), powhiri (a welcome ceremony) borrowed 5-100». from Maori. Abstract: The aim of this article is to review the Maori research as the unique language One of the significant influences on the development of New and cultural identity of New Zealand. We have discovered that the most distinctive Zealand English has been contact with the Maori language and feature of New Zealand English as the national variety is the large number of Maori with Maori cultural traditions. This is reflected in the presence of words and phrases related to indigenous Maori cultural traditions, many of which have become part of general New Zealand culture, as well as to the flora and fauna of New a large number of Maori words in common use in New Zealand Zealand, along with place names. -

Alcohol Use and Tertiary Students in Aotearoa – New Zealand

Alcohol Use and Tertiary Students in Aotearoa – New Zealand ALAC Occasional Publication No. 21 June 2004 ISBN 0-478-11621-7 ISSN 1174-2801 Prepared for ALAC by David Towl, University of Otago ALCOHOL ADVISORY COUNCIL OF NEW ZEALAND Kaunihera Whakatupato Waipiro o Aotearoa P O Box 5023 Wellington New Zealand www.alac.org.nz and www.waipiro.org.nz CONTENTS Introduction.....................................................................................................1 Executive Summary........................................................................................2 Alcohol-Related Harm .................................................................................................... 2 Specific Evaluated Strategies......................................................................................... 2 The Way Forward........................................................................................................... 5 Tertiary Students and Alcohol ........................................................................6 New Zealand Studies ..................................................................................................... 6 Alcohol as Part of the Student Culture ........................................................................... 7 Alcohol-Related Harm Among Tertiary Students.......................................................... 10 Strategies to Reduce Alcohol-Related Harm Among Tertiary Students .......12 Controlling Alcohol Supply .......................................................................................... -

The University of Waikato, Hamilton, New Zealand Hamilton, of University the Waikato, to Study in 2011 Choosing Students – for Prospectus International

THE UNIVERSITY OF WAIKATO, HAMILTON, NEW ZEALAND HAMILTON, WAIKATO, THE UNIVERSITY OF The University of Waikato, Hamilton, New Zealand International Prospectus – For students choosing to study in 2011 INTERNATIONAL PROSPECTUS PROSPECTUS INTERNATIONAL THERE’S NO STOPPING YOU E KORE E TAEA TE AUKATI I A KOE For students choosing to study in 2011 students choosing For 2011 The University of Waikato Waikato International Private Bag 3105 Phone: +64 7 838 4439 Hamilton 3240 Fax: +64 7 838 4269 New Zealand Email: [email protected] Website: www.waikato.ac.nz Website: www.waikato.ac.nz/international ©The University of Waikato, June 2010. twitter.com/ StudyAbroad http:// _UOW Keep up-to-date up-to-date Keep latest news latest news and events with the with the Find us on uson Find facebook TTH FM Te Timatanga Hou Campus map College Hall TG TT TW TX TL TC TA Orchard Park 194H Te Kohanga Reo TSR Creche MS6 CRC Te Kura Kaupapa MS1 Maori o Toku ‘Station MS3 Mapihi Maurea Cafè’ MS5 B ELT MS4 Unisafe BX ‘Momento’ MS9 MSB UL3 MS8 Library Academy Bennetts Bookshop M 2 RB 1 NIWA Oranga Village Green LAW L TEAH A KP Landcare Student Research The Union SP Cowshed K Student SUB Village Rec S Centre FC1 SRC J Aquatic F G Research FC2 Centre I E CONF Chapel CHSS TRU Student LAIN R D Services Bryant EAS Hall LITB C ITS BL LSL GWSP Find us on iTunes U http://picasaweb. google.com/ Waikato. International 1 Contents 04 20 CHOOSE WAIKATO CHOOSE YOUR SUBJECT Welcome 4 Subjects 20 Why New Zealand? 6 Why Waikato? 8 Our beautiful campus – (65 hectares/160 acres) -

2020/2021 Otara-Papatoetoe Excellence Awards Form Preview

2020/2021 Otara-Papatoetoe Excellence Awards Form Preview Welcome / He mihi Otara- Papatoetoe Local Board Pursuit of Excellence Awards The Otara- Papatoetoe Local Board has awards available to recognise and celebrate the contributions of the local applicants Purpose of the Awards The Otara-Papatoetoe Local Board is committed to supporting local residents and organisations to realise their full potential and reaching excellence. Otara-Papatoetoe is a diverse community with talented people and excellent services and the board is keen to assist their development. The purpose of this award is to provide financial assistance to those Otara-Papatoetoe residents and groups who will represent the area to demonstrate their excellence in conference and events. The award is from $150 to $2000. Objectives of the Awards The objectives of the award are: • Celebrate excellence of the Otara-Papatoetoe community and its people. • To assist applicants to build their capacity in serving the community • To promote diverse participation in local government and civic life • To foster the development of a sustainable workforce for local industry and surrounds • To strengthen the development of community cohesion in Ōtara-Papatoetoe. Application criteria This award is open to people who: • are NZ Resident/Citizen living in the Ōtara-Papatoetoe Local Board Area • show excellent and outstanding achievements • demonstrate leadership potential or community contribution during the past 12 months • have been accepted to attend a conference or event either in New Zealand or overseas that will develop their leadership potential Those who receive an award must provide a written report to the board. How to apply Page 1 of 7 2020/2021 Otara-Papatoetoe Excellence Awards Form Preview All applications must be completed and submitted using this online application form. -

The Otara Case of Strengthening Community Entrepreneur Deliberately Staged Affair, Unlike 'Market-Following'

FROM CULTURAL TO ECONOMIC CAPITAL: COl\fMUNITY EMPLOYMEMT CREATION IN OTARA Anne de Bruin Massey University, Albany Campus Abstract This paper stresses the needfor community responses to the ethnic unemployment problem in New Zealand. It aims to show the potential for direct employment creation on the basis of a community entrepreneurship model as well as a widened definition ofhuman capital, using case study ofthe labour market disadvantaged community ofOtara, in South Auckland. Projects harnessing cultural and ethnic riches to create Otara as an attractive visitor destination undertaken by Enterprise Otara (EO) are examined. A participatory research methodology, chiefly formative evaluation is used. ·This paper seeks to break down a prevalent view that grassroots responses to unemployment are necessarily small-scale ventures and to get away from the 'small is beautiful' mind-set when Local Employment Initiatives (ILEs) are involved. Additionally, the collaborative role of 'outsiders ' in the 'bottom-up' approach to employment creation is shown to be important in 'getting things moving' at the community level. Constraints faced by community organisations are highlighted. The importance of ILEs and the partnership concept in the mitigation of high unemployment in disadvantaged communities, is affirmed. Ethnic minority groups are presently over-represented among substitution between labour and capital contributes to deter the unemployed. Unemployment statistics from the House mining whether additional demand for labour will accom hold Labour Force Survey for the September 1996 quarter, pany this response and result in employment growth. By shows a seasonally adjusted unemployment rate of 6.3%. contrast, market-leading manages change to create demand Closer examination reveals continuing significant differ and employment growth which would not otherwise have ences between European/Pakeha rates of unemployment occurred. -

Copy of Stats 2002 Copy

PresbyteryofSouthAuckland Membership AverageJuneAttendance Roll Baptism Other Worship ChristianEduc. e r g a g n r i C r 3 n r e v i 3 3 i t 5 e l 1 v e 1 1 g v a 5 2 a v o r o r r s r r 3 3 o n 2 t o e o e k d o e 5 e 1 1 a t 5 t v i 7 d o p p n d n s d 5 2 5 d 5 r t r r 6 s o 1 n 3 u o a n a n n 5 6 2 n 6 e e e a r - o - a t 3 1 h a o d 6 t u o U d r d s i n e o P o y - 6 t 1 t r T n s t s 3 n e n s v e t p r n b 6 2 t C n a r a l r a l s 3 v 1 o d s U U u p e e 2 t e r a e u d l u e 1 r m i r n 3 e O l u d s l o e r e d n n e u Y d t r e d l i d a l 1 l l a n l h h f l i e e e Y d e A t i a A P n l a l u a 6 u r r n s s C h m u h l A o t a a d 6 2 d d m i e o l n m s M e l l l o a C C i i e 2 A t e n e u o l M e M d C e F l a i Y l l h h l l o t F e d a F U e a l a o l a a m C C a T t l A t a m h a M e c o a m i o e t e M F T M e d T s o F F e u T o D H 1 Beachlands-MaraetaiPresbyterianChurch 41 1 7 21 2 10 2 1 1 100 24 41 14 1 23 10 17 30 20 2 Clevedon:StAndrewsPresbyterianChurch 119 6 64 11 3 32 3 7 2 1 172 59 224 33 16 126 26 11 71 69 56 51 3 ConiferGrove-Takanini:StAidansParish 30 1 11 9 7 2 3 14 22 44 16 5 26 6 1 12 22 6 12 4 FranklinWestCo-operating 67 21 29 9 8 9 0 0 0 110 14 38 4 26 10 0 12 9 1 10 21 Manukau-YungnakPresbyChurch * 29 5 10 3 11 6 15 16 30 8 5 11 8 4 10 11 20 5 Manurewa:StAndrewsPresbyterianChurch 228 2 40 274 60 30 59 6 Manurewa:StPaulsPresbyterianChurch 184 7 91 12 10 54 10 14 1 8 150 44 200 24 10 106 20 9 75 32 10 20 7 Otara-EastTamaki-ChurchOfTheGoodShepherd -

Interweaving in New Zealand Culture: a Design Case Study

Interweaving in New Zealand Culture: a Design Case Study D WOOD Abstract Carin Wilson is one of New Zealand’s significant designers and makers of studio furniture. This analysis of his career is enmeshed with New Zealand contemporary craft history, and the national Pākehā (non-Māori) organization that advocated for craft issues and education from 1965 to 1992. During this period and subsequently, Wilson negotiated his bi-cultural heritage to engage in one-of-a-kind furniture-making as well as benefit non-Māori and Māori communities and the nation. Unlike New Zealand’s coat-of-arms, which portrays its founding cultures as equal yet separate, Wilson’s career shows that New Zealand’s cultures merge into each other, manifesting in hybrid individuals and communities. Figure 1: “New Zealand Coat of Arms 1956,” Ministry for Culture and Heritage, accessed May 30 2011, http://www.nzhistory.net.nz/media/photo/new-zealand-coat-arms-1911-1956. The New Zealand coat-of-arms (Figure 1) attests to the dual nature of the country’s culture. On the left a European woman stands for the Pākehā segment of society whose ancestors came to the South Pacific in the eighteenth and nineteenth-centuries seeking seals, whales, timber, gold and territory; on the right a Māori rangatira represents the indigenous inhabitants whose land and coastal waters contained what was sought after.1 The figures stand in the same plane, metaphorically indicative of the Treaty of Waitangi, New Zealand’s founding constitutional document. This 1956 version of the coat-of-arms was originally designed in 1911.2 Although the graphic design was refined and updated, the New Zealand government still chose to portray the country as having two mutually exclusive races and cultures.