Designed Landscapes, 1875-1980

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Historic-Cultural Monument (HCM) List City Declared Monuments

Historic-Cultural Monument (HCM) List City Declared Monuments No. Name Address CHC No. CF No. Adopted Community Plan Area CD Notes 1 Leonis Adobe 23537 Calabasas Road 08/06/1962 Canoga Park - Winnetka - 3 Woodland Hills - West Hills 2 Bolton Hall 10116 Commerce Avenue & 7157 08/06/1962 Sunland - Tujunga - Lake View 7 Valmont Street Terrace - Shadow Hills - East La Tuna Canyon 3 Plaza Church 535 North Main Street and 100-110 08/06/1962 Central City 14 La Iglesia de Nuestra Cesar Chavez Avenue Señora la Reina de Los Angeles (The Church of Our Lady the Queen of Angels) 4 Angel's Flight 4th Street & Hill Street 08/06/1962 Central City 14 Dismantled May 1969; Moved to Hill Street between 3rd Street and 4th Street, February 1996 5 The Salt Box 339 South Bunker Hill Avenue (Now 08/06/1962 Central City 14 Moved from 339 Hope Street) South Bunker Hill Avenue (now Hope Street) to Heritage Square; destroyed by fire 1969 6 Bradbury Building 300-310 South Broadway and 216- 09/21/1962 Central City 14 224 West 3rd Street 7 Romulo Pico Adobe (Rancho 10940 North Sepulveda Boulevard 09/21/1962 Mission Hills - Panorama City - 7 Romulo) North Hills 8 Foy House 1335-1341 1/2 Carroll Avenue 09/21/1962 Silver Lake - Echo Park - 1 Elysian Valley 9 Shadow Ranch House 22633 Vanowen Street 11/02/1962 Canoga Park - Winnetka - 12 Woodland Hills - West Hills 10 Eagle Rock Eagle Rock View Drive, North 11/16/1962 Northeast Los Angeles 14 Figueroa (Terminus), 72-77 Patrician Way, and 7650-7694 Scholl Canyon Road 11 The Rochester (West Temple 1012 West Temple Street 01/04/1963 Westlake 1 Demolished February Apartments) 14, 1979 12 Hollyhock House 4800 Hollywood Boulevard 01/04/1963 Hollywood 13 13 Rocha House 2400 Shenandoah Street 01/28/1963 West Adams - Baldwin Hills - 10 Leimert City of Los Angeles May 5, 2021 Page 1 of 60 Department of City Planning No. -

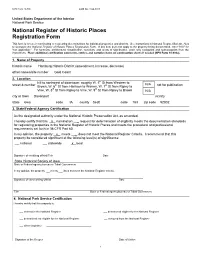

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin, How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional certification comments, entries, and narrative items on continuation sheets if needed (NPS Form 10-900a). 1. Name of Property historic name Hamburg Historic District (amendment, increase, decrease) other names/site number Gold Coast 2. Location th hill to northwest of downtown: roughly W. 5 St from Western to N/A street & number Brown, W. 6th St from Harrison to Warren, W. 7th St from Ripley to not for publication th th Vine, W. 8 St from Ripley to Vine, W. 9 St from Ripley to Brown N/A city or town Davenport vicinity state Iowa code IA county Scott code 163 zip code 52802 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this x nomination _ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property x_ meets _ does not meet the National Register Criteria. -

Books Added to Benner Library from Estate of Dr. William Foote

Books added to Benner Library from estate of Dr. William Foote # CALL NUMBER TITLE Scribes and scholars : a guide to the transmission of Greek and Latin literature / by L.D. Reynolds and N.G. 1 001.2 R335s, 1991 Wilson. 2 001.2 Se15e Emerson on the scholar / Merton M. Sealts, Jr. 3 001.3 R921f Future without a past : the humanities in a technological society / John Paul Russo. 4 001.30711 G163a Academic instincts / Marjorie Garber. Book of the book : some works & projections about the book & writing / edited by Jerome Rothenberg and 5 002 B644r Steven Clay. 6 002 OL5s Smithsonian book of books / Michael Olmert. 7 002 T361g Great books and book collectors / Alan G. Thomas. 8 002.075 B29g Gentle madness : bibliophiles, bibliomanes, and the eternal passion for books / Nicholas A. Basbanes. 9 002.09 B29p Patience & fortitude : a roving chronicle of book people, book places, and book culture / Nicholas A. Basbanes. Books of the brave : being an account of books and of men in the Spanish Conquest and settlement of the 10 002.098 L552b sixteenth-century New World / Irving A. Leonard ; with a new introduction by Rolena Adorno. 11 020.973 R824f Foundations of library and information science / Richard E. Rubin. 12 021.009 J631h, 1976 History of libraries in the Western World / by Elmer D. Johnson and Michael H. Harris. 13 025.2832 B175d Double fold : libraries and the assault on paper / Nicholson Baker. London booksellers and American customers : transatlantic literary community and the Charleston Library 14 027.2 R196L Society, 1748-1811 / James Raven. -

City of Beverly Hills

HISTORIC RESOURCES SURVEY REPORT: PART I: HISTORIC RESOURCES SURVEY UPDATE PART II: AREA 4 MULTI-FAMILY RESIDENCE SURVEY City of Beverly Hills Prepared for City of Beverly Hills Planning and Community Development Department 455 North Rexford Drive Beverly Hills, California 90210 Prepared by PCR Services Corporation One Venture, Suite 150 Irvine, California 92618 June 2004 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page EXECUTIVE SUMMARY. 1 I. INTRODUCTION 1 A. STATEMENT OF PURPOSE 1 B. PROJECT BACKGROUND 1 C. PROJECT DESCRIPTION 3 D. PROJECT LOCATION 3 II. PROJECT METHODOLOGY 4 A. PREVIOUS SURVEY METHODOLOGY 4 B. PRE-FIELD RESEARCH 4 C. FIELDWORK 4 D. PHOTOGRAPHY 5 E. RESEARCH ANT) EVALUATION 5 F. DATABASE 5 G. PREPARATION OF FINAL PRODUCTS 5 III. HISTORIC CONTEXT 7 IV. ARCHITECTURAL CHARACTER 17 ASSOCIATED ARCHITECTURAL STYLES 17 V. DEFINITIONS AN]) CRITERIA 19 A. NATIONAL REGISTER CRITERIA 19 B. EVALUATION OF INTEGRITY 19 C. RELOCATION 21 D. CALIFORNIA REGISTER CRITERIA 22 E. CALIFORNIA OFFICE of HISTORICAL PRESERVATION SURVEY METHODOLOGY 22 F. CITY OF BEVERLY HILLS 23 VI. FINDINGS AND CONCLUSIONS 25 A. SURVEY RESULTS 25 B. HISTORIC RESOURCES SURVEY UPDATE 25 C. AREA 4 MULTI-FAMILY RESIDENCE SURVEY 41 VII. RECOMMENDATIONS 51 A. INTRODUCTION 51 B. HISTORIC RESOURCES SURVEY UPDATE 51 C. AREA 4 MULTI-FAMILY RESIDENCE SURVEY 52 D. PRESERVATION STRATEGIES 52 City of Beverly Hills Historic Resources Survey Report PCR Services Corporation June 2004 TABLE OF CONTENTS VIII. APPENDICES 54 Appendix A: National Register Status Codes Categories Appendix B: Database Property Listing: Historic Resources Survey Update Appendix C: Database Property Listing: Area 4 Multi-Family Residence Survey Appendix D: Database Property Listing: Area 4 Multi-Family Residence Survey, Potential Historic Districts Appendix E: Historic Resources Survey Update. -

Historic-Cultural Monument (HCM) List City Declared Monuments

Historic-Cultural Monument (HCM) List City Declared Monuments No. Name Address CHC No.CF No. Adopted Notes 1 Leonis Adobe 23537 Calabasas Road 8/6/1962 2 Bolton Hall 10116 Commerce Avenue 8/6/1962 3 Nuestra Senora la Reina de Los 100-110 Cesar E. Chavez Ave 8/6/1962 Angeles (Plaza Church) & 535 N. Main St 535 N. Main Street & 100-110 Cesar Chavez Av 4 Angel's Flight 4th Street & Hill8/6/1962 Dismantled 05/1969; Relocated to Hill Street Between 3rd St. & 4th St. in 1996 5 The Salt Box (Former Site of) 339 S. Bunker Hill Avenue 8/6/1962 Relocated to (Now Hope Street) Heritage Square in 1969; Destroyed by Fire 10/09/1969 6 Bradbury Building 216-224 W. 3rd Street 9/21/1962 300-310 S. Broadway 7 Romulo Pico Adobe (Rancho Romulo) 10940 Sepulveda Boulevard 9/21/1962 8 Foy House 1335-1341 1/2 Carroll Avenue 9/21/1962 9 Shadow Ranch House 22633 Vanowen Street 11/2/1962 10 Eagle Rock 72-77 Patrician Way 11/16/1962 7650-7694 Scholl Canyon Road Eagle Rock View Drive North Figueroa (Terminus) 11 West Temple Apartments (The 1012 W. Temple Street 1/4/1963 Rochester) 12 Hollyhock House 4800 Hollywood Boulevard 1/4/1963 13 Rocha House 2400 Shenandoah Street 1/28/1963 14 Chatsworth Community Church 22601 Lassen Street 2/15/1963 (Oakwood Memorial Park) 15 Towers of Simon Rodia (Watts 10618-10626 Graham Avenue 3/1/1963 Towers) 1711-1765 E. 107th Street 16 Saint Joseph's Church (site of) 1200-1210 S. -

Elysian Park Natural Resources Plant Lists

ELYSIAN PARK NATURAL RESOURCES PLANT LISTS ELYSIAN PARK NATURAL RESOURCES APPENDIX NR-2 Prepared for: Withers & Sandgren, Ltd. Landscape Architecture & Planning 3467 Ocean View Blvd., Suite A Glendale, CA 91208 (818) 236-3006 Prepared By: Verna Jigour Associates Conservation Ecology & Design Services 3318 Granada Avenue Santa Clara, CA 95051 (408) 246-4425 May 2005 ELYSIAN PARK NATURAL RESOURCES PLANT LISTS Introduction Plant list tables are provided for the following five associations: Woodland Transition Zones & Barrier Plants Scrubland Transition Zones & Barrier Plants Oak Woodland Restoration & Barrier Plants Walnut/Oak Woodland Restoration & Barrier Plants Scrubland Restoration & Barrier Plants All of the plant associations are designed to contribute to parklands sustainability via reduced water needs and/or adaptation to slope or ridgeline environmental conditions. To ensure success it is important to select species appropriate for each site, paying close attention to each species’ sun exposure/ slope aspect and water needs as indicated in the tables. Group plants with similar exposure and water requirements together for maximum irrigation efficiency in the transition zones, and long-term sustainability in the case of restoration plantings. Transition zone plantings may receive some supplemental irrigation, but this should be tapered off in the sub-zone transitions to the naturalized parklands. This same principle is applicable to fuel modification zones. Restoration plantings will likely benefit from temporary irrigation during the initial establishment period, but should be tapered off after the first year or two. The transition zone plant lists are designed to apply to the zones between highly manicured and exotic parklands, such as the Chavez Ravine Arboretum, and the more or less wild parklands matrix. -

California Garden Clubs List of Arboretum & Botanic Gardens

California Garden Clubs List of Arboretum & Botanic Gardens Adamson House & Malibu Museum 23200 Pacific Coast Highway 310-456-8432 Malibu, CA 90265 adamsonhouse.org Alice Keck Park Memorial Gardens 1600 Santa Barbara St. 805-564-5418 Santa Barbara, CA 93101 Alice Keck Park Memorial Garden Alta Vista Gardens 1270 Vale Terrace Dr. 760-945-3954 Vista, CA 92084 altavistagardens.org Arboretum at CSU Sacramento Arboretum Way 916-278-6011 Sacramento, CA 95826 Sacramento State Arboretum Arizona Cactus Garden Quarry Rd. on Stanford Campus 650-723-7459 Stanford, CA 94305 Stanford Cactus Garden Arlington Gardens 275 Arlington Dr. 626-578-5434 Pasadena, CA 91105 arlingtongardenspasadena.com Balboa Park Gardens 1549 El Prado 619-239-0512 San Diego, CA 92101-1660 balboapark.org/explore Berkeley Municipal Rose Garden 1200 Euclid Ave. 510-981-6637 Berkeley, CA 94708 Berkley Rose Garden Blake Garden at UC Berkeley 70 Rincon Road 510-524-2449 Kensington, CA 94707 botanicgarden.ced.berkeley Botanic Garden at CSU Northridge 18111 Nordhoff St. 818-677-3496 Northridge, CA 91330-8303 Northridge State Botanic Garden Casa del Herrero 1387 East Valley Rd. 805-565-5653 Montecito, CA 93108 casadelherrero.com Chavez Ravine Arboretum 929 Academy Rd. 213-485-3287 Los Angeles, CA 90012 www.laparks/chavezravine.org Chico University Arboretum 44 West 1st Street 530-898-4636 Chico, CA 95929 Chico University Arboretum 1 Clovis Botanical Garden 945 No. Clovis Ave. 559-298-3091 Clovis, CA 93611 clovisbotanicalgarden.org Conejo Valley Botanic Garden 400 W. Gainsborough Rd. 805-494-7630 Thousand Oaks, CA 91360 conejogarden.org Conservatory of Flowers 100 J.F. -

London | 24 March 2021 March | 24 London

LONDON | 24 MARCH 2021 MARCH | 24 LONDON LONDON THE FAMILY COLLECTION OF THE LATE COUNTESS MOUNTBATTEN OF BURMA 24 MARCH 2021 L21300 AUCTION IN LONDON ALL EXHIBITIONS FREE 24 MARCH 2021 AND OPEN TO THE PUBLIC 10 AM Saturday 20 March 12 NOON–5 PM 34-35 New Bond Street Sunday 21 March London, W1A 2AA 12 NOON–5 PM +44 (0)20 7293 5000 sothebys.com Monday 22 March FOLLOW US @SOTHEBYS 10 AM–5 PM #SothebysMountbatten Tuesday 23 March 10 AM–5 PM TO LEARN MORE ABOUT THE PROPERTY IN THIS SALE, PLEASE VISIT This page SOTHEBYS.COM/L21300 LOT XXX UNIQUE COLLECTIONS SPECIALISTS ENQUIRIES FURNITURE & DECORATIVE ART MIDDLE EAST & INDIAN SALE NUMBER David Macdonald Alexandra Roy L21300 “BURM” [email protected] [email protected] +44 20 7293 5107 +44 20 7293 5507 BIDS DEPARTMENT Thomas Williams MODERN & POST-WAR BRITISH ART +44 (0)20 7293 5283 Mario Tavella Harry Dalmeny Henry House [email protected] Thomas Podd fax +44 (0)20 7293 6255 +44 20 7293 6211 Chairman, Sotheby’s Europe, Chairman, UK & Ireland Senior Director [email protected] [email protected] +44 20 7293 5497 Chairman Private European +44 (0)20 7293 5848 Head of Furniture & Decorative Arts ANCIENT SCULPTURE & WORKS Collections and Decorative Arts [email protected] +44 (0)20 7293 5486 OF ART Telephone bid requests should OLD MASTER PAINTINGS be received 24 hours prior +44 (0)20 7293 5052 [email protected] Florent Heintz Julian Gascoigne to the sale. This service is [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] offered for lots with a low estimate +44 20 7293 5526 +44 20 7293 5482 of £3,000 and above. -

GC 1323 Historic Sites Surveys Repository

GC 1323 Historic Sites Surveys Repository: Seaver Center for Western History Research, Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County Span Dates: 1974-1996, bulk 1974-1978 Conditions Governing Use: Permission to publish, quote or reproduce must be secured from the repository and the copyright holder Conditions Governing Access: Research is by appointment only Source: Surveys were compiled by Tom Sitton, former Head of History Department, Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County Background: In 1973, the History Department of the Natural History Museum was selected to conduct surveys of Los Angeles County historic sites as part of a statewide project funded through the National Preservation Act of 1966. Tom Sitton was appointed project facilitator in 1974 and worked with various historical societies to complete survey forms. From 1976 to 1977, the museum project operated through a grant awarded by the state Office of Historic Preservation, which allowed the hiring of three graduate students for the completion of 500 surveys, taking site photographs, as well as to help write eighteen nominations for the National Register of Historic Places (three of which were historic districts). The project concluded in 1978. Preferred Citation: Historic Sites Surveys, Seaver Center for Western History Research, Los Angeles County Museum of Natural History Special Formats: Photographs Scope and Content: The Los Angeles County historic site surveys were conducted from 1974 through 1978. Compilation of data for historic sites continued beyond 1978 until approximately 1996, by way of Sitton's efforts to add application sheets prepared for National Register of Historic Places nominations. These application forms provide a breadth of information to supplement the data found on the original survey forms. -

Costume Institute Records, 1937-2008

Costume Institute Records, 1937-2008 Finding aid prepared by Arielle Dorlester, Celia Hartmann, and Julie Le Processing of this collection was funded by a generous grant from the Leon Levy Foundation This finding aid was generated using Archivists' Toolkit on August 02, 2017 The Metropolitan Museum of Art Archives 1000 Fifth Avenue New York, NY, 10028-0198 212-570-3937 [email protected] Costume Institute Records, 1937-2008 Table of Contents Summary Information .......................................................................................................3 Historical note..................................................................................................................... 4 Scope and Contents note.....................................................................................................6 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 6 Related Materials .............................................................................................................. 7 Controlled Access Headings............................................................................................... 7 Collection Inventory............................................................................................................9 Series I. Collection Management..................................................................................9 Series II. Curators' and Administrators' Files............................................................ -

Los Angeles MSR Appendix A

LAFCO Local Agency Formation Commission for Los Angeles County Los Angeles MSR Appendix A LOS ANGELES MUNICIPAL SERVICE CITY OF BEVERLY HILLS APPENDIX A Fire Service Services Provided Service Demand Fire Suppression DirectStatistical Base Year 2005 Emergency Medical Services DirectTotal Service Calls 5,395 Ambulance Transport Direct % EMS 60% Hazardous Materials NA % Fire 2% Air Rescue & Ambulance Helicopter NA % False Alarm 22% Fire Suppression Helicopter Mutual Aid % Fire & Other 24% Public Safety Answering Point FD/PD PSAP % Other 16% Fire/EMS Dispatch DirectCalls Per 1,000 People 150 Service Adequacy Resources ISO Rating 1 Fire Stations in the City 3 Average Response Time 3:30 Min.Fire Stations Serving City 3 Response Time Base Year 2005 Total Staff 3 Response Time Includes Dispatch No Total Uniform Staff 89 Response Time Note Sworn Staff per Station 82 Service Challenges Sworn Staff per 1,000 2.3 None Staffing Base Year 2005 Infrastructure Needs/Deficiencies The current system of redundant dispatch centers is inefficient when requesting additional resouirces. Fire Stations 1, 2 and 3 are in need of rehabilitation. New Facilities Regional Collaboration Mutual Aid Providers: LA City and County Yes Automatic Aid Providers: LA City and County Beverly Hills Fire Department Facilities Year Station Location Condition Built Staff per Shift Equipment 4 Engines 1 Truck 1 Battalion Chief 2 Rescue No. 1 Headquarters 445 N. Rexford Drive Good 1914 17 firefighters per shift Ambulances No. 2 1100 Coldwater Canyon Good 1914 4 firefighters per shift -

Historic - Cultural Monuments (HCM) Listing City Declared Monuments

Historic - Cultural Monuments (HCM) Listing City Declared Monuments Note: Multiple listings are based on unique names and addresses as supplied by the Departments of Cultural Affairs, Building and Safety and the Department of City Planning Office of Historic Resources (OHR). No. Name Address CPC No. CF No. Adopted Demolished 1 Leonis Adobe 23537 Calabasas Road 8/6/1962 2 Bolton Hall 10116 Commerce Avenue 8/6/1962 3 Nuestra Senora la Reina de Los 535 N. Main Street & 100-110 8/6/1962 Angeles (Plaza Church) Cesar Chavez Av 100-110 Cesar E. Chavez Ave & 535 N. Main St 4 Angel's Flight (Dismantled 5/69) Hill Street & 3rd Street 8/6/1962 5 The Salt Box (Destroyed by Fire) 339 S. Bunker Hill Avenue 8/6/1962 1/1/1969 6 Bradbury Building 300-310 S. Broadway 9/21/1962 216-224 W. 3rd Street 7 Romulo Pico Adobe (Rancho Romulo) 10940 Sepulveda Boulevard 9/21/1962 8 Foy House 1335-1341 1/2 Carroll Avenue 9/21/1962 9 Shadow Ranch House 22633 Vanowen Street 11/2/1962 10 Eagle Rock Eagle Rock View Drive 11/16/1962 North Figueroa (Terminus) 72-77 Patrician Way 7650-7694 Scholl Canyon Road 11 West Temple Apartments (The 1012 W. Temple Street 1/4/1963 2/14/1979 Rochester) 12 Hollyhock House 4800 Hollywood Boulevard 1/4/1963 13 Rocha House 2400 Shenandoah Street 1/28/1963 14 Chatsworth Community Church 22601 Lassen Street 2/15/1963 (Oakwood Memorial Park) 15 Towers of Simon Rodia (Watts 10618-10626 Graham Avenue 3/1/1963 Towers) 1711-1765 E.