EAHN 6Th International Meeting Conference Proceedings 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

548 Call-And-Response

Proceedings of the Society of Architectural Historians Australia and New Zealand Vol. 32 Edited by Paul Hogben and Judith O’Callaghan Published in Sydney, Australia, by SAHANZ, 2015 ISBN: 978 0 646 94298 8 The bibliographic citation for this paper is: Sawyer, Mark. “Call-and-Response: Group Formation and Agency enacted through an Architectural Magazine, its Letters and Editorials.” In Proceedings of the Society of Architectural Historians, Australia and New Zealand: 32, Architecture, Institutions and Change, edited by Paul Hogben and Judith O’Callaghan, 548-557. Sydney: SAHANZ, 2015. Mark Sawyer, University of Western Australia Call-and-Response: Group Formation and Agency enacted through an Architectural Magazine, its Letters and Editorials Current scholarship is increasingly focusing on the productive alliances and relationships arising between late twentieth-century architects and theorists. As independent architectural periodicals are mined one-by-one for their historical value and used to narrate the permutations of the still recent past, the ‘little magazine’ is being broadly characterised as a node around which avant-garde groups have consolidated their identities and agendas. What is missing from current scholarship is an adequate explanation of the type of agency exhibited by architectural groups and the role that architectural publishing plays in enacting this agency. This paper is an investigation into the mechanics of architectural group formation and agency considering some important mechanisms by which groups, alliances, and their publications have participated in the development of an architectural culture. This paper investigates the relationships that developed between a number of interrelated groups emerging out of Melbourne’s architectural milieu in the final decades of the twentieth century. -

Lycée Français Charles De Gaulle Damascus, Syria

2013 On Site Review Report 4032.SYR by Wael Samhouri Lycée français Charles de Gaulle Damascus, Syria Architect Ateliers Lion Associés, Dagher, Hanna & Partners Client French Ministry of Foreign Affairs Design 2002 - 2006 Completed 2008 Lycée Français Charles de Gaulle Damascus, Syria I. Introduction The Lycée Français Charles de Gaulle in Damascus, a school that houses 900 students from kindergarten up to baccalaureate level, is a garden-like school with classrooms integrated into an intricate system of courtyards and green patios. The main aim of the design was to set a precedent: a design in full respect of the environment that aspires to sustainability. Consequently it set out to eliminate air conditioning and use only natural ventilation, cooling, light/shadows and so economise also on running costs. The result is a project that fully reflects its aims and translates them into a special architectural language of forms with rhythms of alternating spaces, masses, gardens and a dramatic skyline rendered by the distinct vertical elements of the proposed solar chimneys. II. Contextual Information A. Brief historical background This is not an ordinary school, one that is merely expected to perform its educational functions although with a distinguishing characteristic: doing everything in French within an Arab country. Rather, it is a school with a great deal of symbolism and history attached to it. To illustrate this, suffice to say that this school, begun in 2006, was formally inaugurated by the French President himself. On a 2008 hot September Damascene morning, in the presence of world media, President Nicolas Sarkozy and the Syrian Minister of Education attended the formal opening of the school, in the hope of establishing a new phase of Franco-Syrian educational relations. -

The English Claim to Gothic: Contemporary Approaches to an Age-Old Debate (Under the Direction of DR STEFAAN VAN LIEFFERINGE)

ABSTRACT MARY ELIZABETH BLUME The English Claim to Gothic: Contemporary Approaches to an Age-Old Debate (Under the Direction of DR STEFAAN VAN LIEFFERINGE) The Gothic Revival of the nineteenth century in Europe aroused a debate concerning the origin of a style already six centuries old. Besides the underlying quandary of how to define or identify “Gothic” structures, the Victorian revivalists fought vehemently over the national birthright of the style. Although Gothic has been traditionally acknowledged as having French origins, English revivalists insisted on the autonomy of English Gothic as a distinct and independent style of architecture in origin and development. Surprisingly, nearly two centuries later, the debate over Gothic’s nationality persists, though the nationalistic tug-of-war has given way to the more scholarly contest to uncover the style’s authentic origins. Traditionally, scholarship took structural or formal approaches, which struggled to classify structures into rigidly defined periods of formal development. As the Gothic style did not develop in such a cleanly linear fashion, this practice of retrospective labeling took a second place to cultural approaches that consider the Gothic style as a material manifestation of an overarching conscious Gothic cultural movement. Nevertheless, scholars still frequently look to the Isle-de-France when discussing Gothic’s formal and cultural beginnings. Gothic historians have entered a period of reflection upon the field’s historiography, questioning methodological paradigms. This -

On Photography, History, and Memory in Spain Hispanic Issues on Line Debates 3 (2011)

2 Remembering Capa, Spain and the Legacy of Gerda Taro, 1936–1937 Hanno Hardt Press photographs are the public memory of their times; their presence in the public sphere has contributed significantly to the pictures in our heads on which we rely for a better understanding of the world. Some photographs have a special appeal, or an extraordinary power, which makes them icons of a particular era. They stand for social or political events and evoke the spirit of a period in history. They also help define our attitudes towards people or nations and, therefore, are important sources of emotional and intellectual power. War photography, in particular, renders imagery of this kind and easily becomes a source of propaganda as well. The Spanish Civil War (1936–39) was the European testing ground for new weapons strategies by the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany. Both aided their respective sides in the struggle between a Popular Front government— supported mainly by left-wing parties, workers, and an educated middle class—and “Nationalist” forces supported by conservative interests, the military, clergy, and landowners. The conflict resulted in about 500,000 deaths, thousands of exiles, and in a dictatorship that lasted until Franco’s death in 1975. It was a time when large-scale antifascist movements such as the Republican army, the International Brigades, the Workers’ Party of Marxist Unification, and anarchist militias (the Iron Column) united in their struggle against the military rebellion led by Francisco Franco. Foreigners joined the International Brigade, organized in their respective units, e.g., the Lincoln Battalion (USA), the British Battalion (UK), the Dabrowski Battalion (Poland), the Mackenzie-Papineau Battalion (Canada), and the Naftali Botwin Company (Poland and Spain, including a Jewish unit). -

The Past, Present, and Future of the Chinese Home an Architectural

Te Past, Present, and Future of the Chinese Home An Architectural Study of the Relationship Between Politics, Culture, and Domestic Space By | Tina Huang | 黄维钰 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Afairs in partial fulfllment of the requirements for the degree of Master in Architecture Carleton University, Ottawa, Ontario ©2021TinaHuang ABSTRACT his thesis analyzes the oscillating cause and effect between State, citizen, Tand architecture by studying the relationship between politics and domestic spaces in China. It explores the development of China from the beginning of the twentieth century through the present and into a speculative future to argue that wider socio-political changes are reflected in the detailed and intimate spaces of the home, and conversely, that the home can act as an agent of political resistance. The timeline in question represents a unique and tumultuous era in the development of modern China, one which dramatically changed the way people in China built their homes, and in turn, lived their lives. By imagining a speculative future condition in which China has undergone another major political and cultural shift, this thesis will consider the past in order to propose a speculative trajectory for the future of domestic Chinese architecture. II ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I want to firstly thank my advisor Natalia for your patience and constant support during this past year, your encouragement throughout the writing of this thesis has been invaluable. To the staff and faculty at the Azrieli School of Architecture and Urbanism, thank you for making the last six years so wonderful. The guidance and support from everyone has been crucial to my educational growth. -

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin, How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional certification comments, entries, and narrative items on continuation sheets if needed (NPS Form 10-900a). 1. Name of Property historic name Hamburg Historic District (amendment, increase, decrease) other names/site number Gold Coast 2. Location th hill to northwest of downtown: roughly W. 5 St from Western to N/A street & number Brown, W. 6th St from Harrison to Warren, W. 7th St from Ripley to not for publication th th Vine, W. 8 St from Ripley to Vine, W. 9 St from Ripley to Brown N/A city or town Davenport vicinity state Iowa code IA county Scott code 163 zip code 52802 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this x nomination _ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property x_ meets _ does not meet the National Register Criteria. -

{PDF EPUB} Towards a Fresh Revolution by Amigos De Durruti Friends of Durruti

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Towards A Fresh Revolution by Amigos de Durruti Friends of Durruti. Audiobook version of the pamphlet Towards a Fresh Revolution, published by the Friends of Durruti group during the Spanish Civil War. A revolutionary theory (with an introduction by Agustín Guillamón) An article published in July 1937 by The Friends of Durruti, large portions of which appeared in the pamphlet “The Revolutionary Message of the ‘Friends of Durruti’” (PDF) that was translated into English via French. Here it is translated in full directly from Spanish for the first time. Views and Comments No. 44 (April 1963) The No. 44 (April 1963) issue of Views and Comments , an anarcho-syndicalist leaning publication produced out of New York by the Libertarian League from 1955 until 1966. A look at the past: the revolutionary career of Joaquín Pérez – Miguel Amorós. A vivid biographical sketch of Joaquín Pérez (1907-2006), based on a manuscript he wrote during the last few years of his life, who joined the CNT at the age of sixteen in the early 1920s, and was, successively, a specialist in the CNT’s Defense Committees in Barcelona during the 1930s, a militiaman in the Durruti Column during the first months of the Civil War, one of the original members of The Friends of Durruti, a fugitive, a prisoner in Montjuich, and then, after escaping from Montjuich as Franco’s forces closed in on the citadel, an exile, first in labor camps in France, and then, after stowing away on a British warship during the evacuation of Brest, in London. -

Newsletter the Society of Architectural Historians

NEWSLETTER THE SOCIETY OF ARCHITECTURAL HISTORIANS APRIL 1967 VOL. XI NO. 2 PUBLISHED FIVE TIMES A YEAR BY THE SOCIETY OF ARCHITECTURAL HISTORIANS 1700 WALNUT STREET, PHILADELPHIA, PA. 19103 GEORGE B. TATUM, PRESIDENT EDITOR: JAMES C. MASSEY, 501 DUKE STREET, ALEXANDRIA, VIRGINIA 22314. ASSOCIATE EDITOR : MARIAN CARD DONNELLY, 2175 OLIVE STREET, EUGENE, OREGON 97405 CHAPTERS PRESIDENTIAL MESSAGE Eastern Virginia (Proposed Chapter) Calvert Walke have asked the editors of the Newsletter for Tazewell, Executive Vice President of the Norfolk His enough space to express my appreciation, and that of torical Society, and other interested SAH members, are the Society, to all who replied to my recent letter proposing the establishment of a new SAH Chapter for asking for advice and assistance. Eastern Virginia. A preliminary meeting was held in Nor The response of those you proposed for member folk on April 27. For information, address, Col. Tazewell ship in the Society has been heartening, while in at 507 Boush Street, Norfolk, Va. creasing contributions from our Patron members and Missouri Valley The Missouri Valley Chapter of the SAH others continue to i11J-prove materially our balance held its organizationa l meeting April 16 at the Nelson in the treasury. We are especially grateful to those Gallery of Art in Kansas City, Mo. The following persons of you who increased your class of membership. were elected to Chapter posts: President - E.F. Corwin, We regret that to date it has not been possible Jr., Architect for the Kansas City Park Department; Vice to acknowledge promptly and individually every President- Ralph T. Coe, Assistant Director of the Nelson contribution of time, thought, and funds, but we trust Gallery of Art; Secretary-Treasurer- Donald Hoffmann, Art those concerned will recognize· that to have done so Critic of the Kansas City Star; Directors - Osmund Overby, under present conditions would have increased our University of Missouri, and Curtis Besinger, University of expenses, thereby diminishing the effectiveness of Kansas. -

Brick Gothic Recovering Atmospheric Versatility Itinerary Route

Brick Gothic Recovering atmospheric versatility Itinerary Route The contemporary dilemma of uniting building character with energy and Latvia Day 1-2 effciency considerations has often led to isolated specialist approaches that Riga overlook synergies in the inherent properties of common construction materials. A study of building traditions before the introduction of large-scale metal Poland Day 3-7 components and conditioning systems, however, reveals a tectonic richness Gdansk stemming from culturally self-aware and inherently economical approaches to Malbork structural and climatic challenges. In the case of the brick gothic architecture Torun of the former Hanseatic League cities, this awareness manifested in muscular buildings with polychrome patterns and bas-relief complexity, assembled from Germany Day 8-18 simple brick masonry units. Of many subsequent pan-European interpretations, Stralsund one British architect devoted to the neo-Gothic - Professor Alan Short - has Wismar Riga exhibited particular virtuosity in adapting this subtle form of exuberance to Lübeck his very different and highly specifc environmental requirements. His work Hamburg demonstrates the enduring versatility of this lineage of architectural expression Bremen in creating atmospheric depth with tectonic sophistication but material economy. Manchester Gdansk Netherlands Day 19-21 Lichfeld The backsteingotik, ‘brick gothic’ in German, partly evolved from a desire Zwolle Stralsund Leicester to reinforce continental culture along the shipping routes of the Hanseatic Amsterdam Lübeck Birmingham Malbork League of allied trading port-cities in the 12th - 15th centuries. With political Wismar and religious tensions as present as the harsh maritime conditions, important England Day 22-32 Bremen Coventry Amsterdam Hamburg commercial and public projects tended to be durable and aesthetically confdent Manchester Zwolle Torun structures, but due to the lack of stone resources, were often built using clay Lichfeld masonry. -

Books Added to Benner Library from Estate of Dr. William Foote

Books added to Benner Library from estate of Dr. William Foote # CALL NUMBER TITLE Scribes and scholars : a guide to the transmission of Greek and Latin literature / by L.D. Reynolds and N.G. 1 001.2 R335s, 1991 Wilson. 2 001.2 Se15e Emerson on the scholar / Merton M. Sealts, Jr. 3 001.3 R921f Future without a past : the humanities in a technological society / John Paul Russo. 4 001.30711 G163a Academic instincts / Marjorie Garber. Book of the book : some works & projections about the book & writing / edited by Jerome Rothenberg and 5 002 B644r Steven Clay. 6 002 OL5s Smithsonian book of books / Michael Olmert. 7 002 T361g Great books and book collectors / Alan G. Thomas. 8 002.075 B29g Gentle madness : bibliophiles, bibliomanes, and the eternal passion for books / Nicholas A. Basbanes. 9 002.09 B29p Patience & fortitude : a roving chronicle of book people, book places, and book culture / Nicholas A. Basbanes. Books of the brave : being an account of books and of men in the Spanish Conquest and settlement of the 10 002.098 L552b sixteenth-century New World / Irving A. Leonard ; with a new introduction by Rolena Adorno. 11 020.973 R824f Foundations of library and information science / Richard E. Rubin. 12 021.009 J631h, 1976 History of libraries in the Western World / by Elmer D. Johnson and Michael H. Harris. 13 025.2832 B175d Double fold : libraries and the assault on paper / Nicholson Baker. London booksellers and American customers : transatlantic literary community and the Charleston Library 14 027.2 R196L Society, 1748-1811 / James Raven. -

The Grunwald Trail

n the Grunwald fi elds thousands of soldiers stand opposite each other. Hidden below the protec- tive shield of their armour, under AN INVITATION Obanners waving in the wind, they hold for an excursion along long lances. Horses impatiently tear their bridles and rattle their hooves. Soon the the Grunwald Trail iron regiments will pounce at each other, to clash in a deadly battle And so it hap- pens every year, at the same site knights from almost the whole of Europe meet, reconstructing events which happened over six hundred years ago. It is here, on the fi elds between Grunwald, Stębark and Łodwigowo, where one of the biggest battles of Medieval Europe took place on July . The Polish and Lithuanian- Russian army, led by king Władysław Jagiełło, crushed the forces of the Teutonic Knights. On the battlefi eld, knights of the order were killed, together with their chief – the great Master Ulrich von Jungingen. The Battle of Grunwald, a triumph of Polish and Lithuanian weapons, had become the symbol of power of the common monarchy. When fortune abandoned Poland and the country was torn apart by the invaders, reminiscence of the battle became the inspiration for generations remembering the past glory and the fi ght for national independence. Even now this date is known to almost every Pole, and the annual re- enactment of the battle enjoys great popularity and attracts thousands of spectators. In Stębark not only the museum and the battlefi eld are worth visiting but it is also worthwhile heading towards other places related to the great battle with the Teutonic Knights order. -

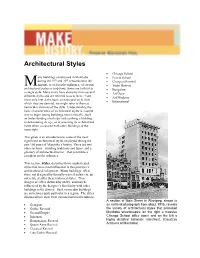

Architectural Style Guide.Pdf

Architectural Styles Chicago School any buildings constructed in Manitoba Prairie School th th during the 19 and 20 centuries bear the Georgian Revival M imprint, or at least the influence, of certain Tudor Revival architectural styles or traditions. Some are faithful to Bungalow a single style. Many more have elements from several Art Deco different styles and are referred to as eclectic. Even Art Moderne more only hint at the basic architectural style from International which they are derived; we might refer to them as vernacular versions of the style. Understanding the basic characteristics of architectural styles is a useful way to begin seeing buildings more critically. Such an understanding also helps in describing a building, in determining its age, or in assessing its architectural value when compared with other buildings of the same style. This guide is an introduction to some of the most significant architectural styles employed during the past 150 years of Manitoba’s history. There are two other sections—building traditions and types, and a glossary of architectural terms—that constitute a complete set for reference. This section, Styles, describes those sophisticated styles that were most influential in this province’s architectural development. Many buildings, often those not designed by formally-trained architects, do not relate at all to these historical styles. Their designs are often dictated by utility, and may be influenced by the designer’s familiarity with other buildings in the district. Such vernacular buildings are sometimes quite particular to a region. The styles discussed here stem from various historical traditions. A section of Main Street in Winnipeg, shown in Georgian an archival photograph from about 1915, reveals Gothic Revival the variety of architectural styles that animated Second Empire Manitoba streetscapes: on the right a massive Italianate Chicago School office tower and on the left a Romanesque Revival highly detailed Italianate storefront.