Alienation and Reunion of the Characters of the Ramayana

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cradle Tales of Hinduism Bv the Same Author, Footfalls of Indian History

NY PUBLIC LIBRARY THE BRANCH LIBRARIES 3 3333 07251 1310 Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2007 with funding from IVIicrosoft Corporation http://www.archive.org/details/cradletalesofhinOOnive CRADLE TALES OF HINDUISM BV THE SAME AUTHOR, FOOTFALLS OF INDIAN HISTORY. With 6 Coloured Plates and 22 other Illustra- tions. Extra crown 8vo, "Js. 6d. net ; 2 R. 8 as. AN INDIAN STUDY OF LOVE AND DEATH. Crown Svo, 2s. 6d. net. THE MASTER AS I SAW HIM. Being Pages from the Life of the Swami Vivekananda. Crown 8vo, 5s. net. STUDIES FROM AN EASTERN HOME. With a Portrait, Prefatory Memoir by S. K. Ratcliffe, and Appreciations from Professor Patrick Geddes, Professor T. K. Cheyne, Mr. H. W. Nevinson, and Mr. Rabindranath Tagore. Crown 8vo, 3J, 6d. net ; i R. 4 as. RELIGION AND DHARMA. Crown 8vo, 3^^. net ; I R. 4 as. This is a book on the Religion of Hinduism, its aims, ideals, and meaning. It appeals especially to those who are students of native life and Religion in India, and particularly to those who have some knowledge of the new movements in thought, art, and religion which are arising among the Indian natives. LONGMANS, GREEN AND CO. BOMBAY, CALCUTTA, AND MADRAS LONDON AND NEW YORK The Indian Story Teller at NigKtfall CRADLE TALES OF HINDUISM BY THE SISTER NIVEDITA (MARGARET E. NOBLE) AUTHOR OF "the WEB OF INDIAN LIFE," ETC. WITH FRONTISPIECE NE'i^r IMPRESSION LONGMANS, GREEN AND CO. HORNBY ROAD, BOMBAY 6 OLD COURT HOUSE STREET, CALCUTTA 167 MOUNT ROAD, MADRAS LONDON AND NEW YORK 1917 All rights reserved v) THE NEW YORK PUBLIC LIRHARY ASTw^, L6NOX AN» T<LDeN FOUNDaTIONI. -

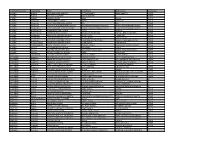

Ujjwal Siddapur.Pdf

GramPanchayatName TownName Name FatherName Mothername CasteGroup NILKUND Hallibail MANGALA SUBBA MARATTI VITTALA MARATTI GIRIJA MARATTI OTHER NILKUND Hallibail SHIVI SHIVU MARATTI BADIYA MARATTI OTHER NILKUND Hallibail yamuna.s. -

THE OPEN COURT. the Nature of Science Is the Economy of Thought

The Open Court A. WEEKLY JOURNAIi Devoted to the Work of Conciliating Religion with Science, Entered at the Chicago Post-Ofl&ce as Second-Class Matter. -OFFICE, 169—175 LA SALLE STREET.- ( Dollars per Year. Vol. III.— 12 Two No. 90. CHICAGO, MAY 16, li Single Copies, I 10 cts. CONTENTS: RISE OF THE PEOPLE OF ISRAEL. I. Prof. Carl POETRY. Heinrich Cornill i6ig Sonnet. Louis Belrose, Jr 1626 FACTS AND TRUTHS. COL. INGERSOLL'S SCIENCE. To The Soul. W. D. Lighthall 1626 W, M. Boucher 1620 CORRESPONDENCE. THE SITAHARANAM ; OR, THE RAPE OF SITA. An Positivism. Louis Belrose, Jr 1626 Episode from the Great Sanskrit Epic "Ramayana." Comtists And Agnostics. R. F. Smith 1626 Prof, .\lbert H. Gunlogsen 1622 Philosophy At Montreal. JIarv Morgan (Gowan Lea.) 1627 THE COMING RELIGION. Charles K. Whipple 1623 Absolute Existence (^With Editorial Note). P 1627 GOD, FREEDOM, AND IMMORTALITY. Editor 1625 FICTION. BOOK REVIEWS, NOTES, ETC. The Lost Manuscript. (Continued.) Gustav Freytag. 1628 the con- REMINGTON TWENTIETHCENTURY ENLARGED AND IMPROVED. Devoted to Secular Religion dnd "THE WEEK," Social Regeneration. Type- A Cafiadian Journal of Politics^ Lit- erature^ Science J and Art. HUGH 0. PENTECOST, Editor. Published every Friday. $3.00 per writer year. $1.00 for Four Months. Contains, besides crisp and pointed editorials WON THE WEEK has entered on its SIXTHf^ear of and contributions from a corps of able writers, the publication, greatly enlarged and improved in every respect, rendering it still more worthy Sunday Addresses of the Editor before Unity Con- the cordial GOLD MEDAL support of every one interested in the maintenance gregation. -

Chaitanya and His Age

SfHH;;;'"7!i.;ili!ii4 : :;:Ji;i':H^;(Ijy"rSi)i?{;;!Hj:?;^i=^ih^: 5 39 CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY Date Due im-^ - t954H SI S&:3^ 1956 eg * WT R IN*6fet)S wiie i^ i* '""'"'^ BL 1245.V36S39'""""^ Chajtanya and his age / 3 1924 022 952 695 Cornell University Library The original of tiiis book is in tine Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924022952695 CHAITANYA AND HIS AGE Chaitanya and His Age {Ramtanu Lahiri Fellowship Lectures for the year 1919 and 1921) By Rai Bahadur Dinesh Chandra Sen, B.A., D.Litt., Fellow, Reader, and Head Examiner of the Calcutta University, Associate Member of the Asiatic Society of Bengal, Author of History of Bengali Language and Literature, the Vaisnaya Literature of MediaLvai IBengal, Chaitanya and his Companions, Typical Selections from Old Bengali Literature, Polk Literature of Bengal, the Bengali Ramayanas, Banga Bhasa-0-Sahitya, etc, etc. Published by the UNIVERSITY OF CALCUTTA 1922 Lc. BL /^/cp-^ /yajT Printed et Atulchandra Bhattachabtta at the Calcutta University Press, Senate House, Calcutta Dedicated To The Hon'ble SIR ASUTOSH MOOKERJEE, Kt., C.S.I., M.A., D.L., D.Sc., Ph.D., F.R.A.S., F.R.S.E., F.A.S.B. Vice-Chancellor of the Calcutta University, whose resolute and heroic attempts to rescue our Alma Mater from destruction at the hour of her great peril may well remind us of the famous line of Jayadeva with the sincere gratitude of the Author " Hail thee O Chaitanya— the victor of my heart, Mark the rhythm of his mystic dance in lofty ecstasy—quite alone. -

The Viṣṇu Purāṇa ANCIENT ANNALS of the GOD with LOTUS EYES

The Viṣṇu Purāṇa ANCIENT ANNALS OF THE GOD WITH LOTUS EYES The Viṣṇu Purāṇa ANCIENT ANNALS OF THE GOD WITH LOTUS EYES Translated from the Sanskrit by McComas Taylor For my grandchildren Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] Available to download for free at press.anu.edu.au ISBN (print): 9781760464400 ISBN (online): 9781760464417 WorldCat (print): 1247155624 WorldCat (online): 1247154847 DOI: 10.22459/VP.2021 This title is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). The full licence terms are available at creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode Cover design and layout by ANU Press Cover image: Vishnu Reclining on Ananta. From Sage Markandeya’s Ashram and the Milky Ocean, c. 1780–1790. Mehrangarh Museum Trust. This edition © 2021 ANU Press Contents Preface xi Acknowledgements xiii Glossary xv Introduction 1 The purāṇas 1 The Viṣṇu Purāṇa 3 Problems with dating 4 Authorship 6 The audience 6 Relationship to other texts 7 The nature of Viṣṇu 10 Viṣṇu and Kṛṣṇa 12 The other avatāras 13 The purāṇic thought-world 14 Divine and semi-divine beings 18 Elements of the Viṣṇu Purāṇa 21 The six books 25 The Sanskrit text 32 Other translations 33 About this translation 34 References 38 Book One: Creation 43 1. Maitreya asks Parāśara about the world 43 2. Parāśara praises Viṣṇu; Creation 45 3. The divisions of time 50 4. Brahmā creates the world anew 52 5. Brahmā creates living beings 57 6. -

A World of Nourishment Reflections on Food in Indian Culture

A WORLD OF NOURISHMENT. REFLECTIONS ON FOOD IN INDIAN CULTURE A WORLD OF NOURISHMENT. Consonanze 3 Today as in the past, perhaps no other great culture of human- kind is so markedly characterised by traditions in the field of nutrition as that of South Asia. In India food has served to express religious values, philosophical positions or material power, and between norms and narration Indian literature has dedicated ample space to the subject, presenting a broad range of diverse or variously aligned positions, and evidence A WORLD OF NOURISHMENT of their evolution over time. This book provides a collection of essays on the subject, taking a broad and varied approach rang- REFLECTIONS ON FOOD IN INDIAN CULTURE ing chronologically from Vedic antiquity to the evidence of our own day, thus exposing, as in a sort of comprehensive outline, many of the tendencies, tensions and developments that have occurred within the framework of constant self-analysis and Edited by Cinzia Pieruccini and Paola M. Rossi reflection. Cinzia Pieruccini is Associate Professor of Indology, and Paola M. Rossi is Lecturer in Sanskrit Language and Literature in the University of Milan. www.ledizioni.it ISBN 978-88-6705-543-2 € 34,00 A World of Nourishment Reflections on Food in Indian Culture Edited by Cinzia Pieruccini and Paola M. Rossi LEDIZIONI CONSONANZE Collana del Dipartimento di Studi Letterari, Filologici e Linguistici dell’Università degli Studi di Milano diretta da Giuseppe Lozza 3 Comitato scientifico Benjamin Acosta-Hughes (The Ohio State University), -

Prayers Addressed to Lord Anjaneya in Sanskrit, Hindi, Tamil and Telugu

Prayers addressed to Lord Anjaneya in Sanskrit, Hindi, Tamil and Telugu Contents 1. Prayers addressed to Lord Anjaneya in Sanskrit, Hindi, Tamil and Telugu ........................................ 1 2. Anjaneya (Hanuman) Ashtotharam ........................................................................................................................ 2 3. Anjaneya Dandakam in Telugu................................................................................................................................. 4 4. Anjaneya Stotram ........................................................................................................................................................... 9 5. Anjaneya Stothra ........................................................................................................................................................... 11 6. Arul migu Anjaneyar , Hanuman thuthi-tamil ................................................................................................... 13 7. Bhajarang Baan.............................................................................................................................................................. 16 8. Ekadasa mukha Hanumath Kavacham ................................................................................................................. 19 9. Hanuman Chalisa .......................................................................................................................................................... 24 10. Hanuman ji ki aarthi ................................................................................................................................................... -

Icoht2015-1107.Pdf

Proceeding of the 3rd International Conference on Hospitality and Tourism Management, Vol. 3, 2015, pp. 58- 67 Copyright © TIIKM ISSN: 2357-2612 online DOI: 10.17501/ icoht2015-1107 RAMAYANA TRAIL TOURS IN SRI LANKA IN THE PERSPECTIVE OF INDIAN TOURIST - A STUDY Ravikumar, L1 and Sarat, K. L2 1 Department of Tourism, Utkal University, India 2 Indian Institute of Tourism and Travel Management, India Abstract Sri Lanka, one of the wonders of Asia is prospering at a fast pace and tourism being one of the most important sectors of its economy. The tourism contributions for its phenomenal growth are in the areas of Beach & Island Tourism and its rich heritage sites. In spite of its growth of inbound tourism from India, there seems to be less attention on the Ramayana trail sites. This study looks into the situation that prevails in Sri Lanka on the promotion of historical sites connected to the Ramayana Trail from the perspective of inbound tourists from India. With the help of descriptive analysis, the study probes into the significance of Sri Lanka’s historical sites connected to the Ramayana Trail, the awareness and perception about the same among the Indian tourists. Based on the study it is revealed that the Ramayana Trail sites in Sri Lanka today are not promoted to the extent to which it becomes significant part of the nation’s historical importance. Lack of promotion and information available makes the Indian tourists unaware of the historical sites of importance in the Ramayana Trail and its immense potential. However, it is understood that most of the tourists were satisfied that historical and heritage sites connected to epic Ramayana trail has been reasonably well promoted by Sri Lanka. -

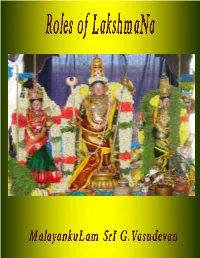

33. Roles of Lakshmana

Sincere thanks to: 1. Mannargudi Sri Srinivasan Narayanan for providing the Sanskrit/Tamil texts and proof reading 2. Nedumtheru SrI Mukund Srinivasan for providing images sadagopan.org 3. Smt.Jayashree Muralidharan for eBook assembly 2 C O N T E N T S Author's special note i Introduction 1 Chapter 1 List of roles LakshmaNa played 6 Chapter 2 LakshmaNa - the baalya sakha 8 Chapter 3 LakshmaNa - the companion 15 Chapter 4 LakshmaNa – the husband of OormiLa 19 Chapter 5 LakshmaNa – the Assistant Administrator 25 Chapter 6 LakshmaNa – the angry young brother 28 sadagopan.org Chapter 7 LakshmaNa – the boat builder 59 Chapter 8 LakshmaNa – the engineer 66 Chapter 9 LakshmaNa – the chef 83 Chapter 10 LakshmaNa – the scavenger 88 Chapter 11 LakshmaNa – the ambassador or envoy or commissioner 114 de affairs Chapter 12 LakshmaNa – the Security Officer or Security guard 160 Chapter 13 LakshmaNa – the Warrior 189 Chapter 14 LakshmaNa – the Minister or counselor or advisor and 308 The Guru Chapter 15 LakshmaNa – the arduous servant 402 nigamanam 431 Appendix Complete list of Sundarasimham-Ahobilavalli eBooks 433 3 sadagopan.org SrI Raama paTTAbhishekam (Thanks:sou.R.Chitralekha) SrI RaamapaTTAbhishekam AUTHOR'S SPECIAL NOTE My respectful praNaamams to my aachaaryaas Sri Mukkur azhagiya singer and prakrutham srimadh azhagiya singer. My sincere praNaamams to my father and father in law who brought me to this level to understand and write on sreemadh raamaayaNam. My sincere thanks to Sri V.Sadagopan, the US based moderator of Oppiliappan yahoo groups and Sri Anbil Ramaswamy with whose blessings, I could do this book. -

The Gospel of Rmakrishna

/Tinu I [ LIBRARY Of UNIvfWIIY j V CAlifOfHlA/ **^ ^^"^., _. IT *rr tfyj 'Jfa tt<9 &f . U THE GOSPEL OF RAMAKRISHNA < I 5, THE GOSPEL OF RAMAKRISHNA AUTHORIZED EDITION PUBLISHED BY THE VEDANTA SOCIETY 135 WEST BOTH STREET NEW YORK COPYRIGHT, 1907, BY SWAMI ABHEDANANDA ENTERED AT STATIONERS' HALL. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. ROBERT DRUMMOND COMPANY, PRINTERS, NEW YORK B/3 Niranjanam Nityam anantarupam, Bhaktdnukampd dhritavigraham vai; Ishdvatdram Parantesham Idyam, Tarn Ramakrishnam Shirasha Namdmah. Salutations to Bhagavan Sri Ramakrishna, the perfect Embodiment of the Eternal Truth which manifests Itself in various forms to help mankind, and the Incarnation of the Supreme Lord who is worshipped by all. HARI OM TAT SAT. 15S PREFACE THIS is the authorized English edition of the "Gospel of Ramakrishna." For the first time in the history of the world's Great Saviours, the exact words of the Master were recorded verbatim by one of His devoted disciples. These words were originally spoken in the Bengali language of India. They were taken down in the form of diary notes by a house- holder disciple, "M." At the request of Sri Ramakrishna's Sannyasin disciples, however, these notes were published at Calcutta during 1902-1903 A.D., in Bengali, in two volumes, " entitled Rdmakrishna Kathdmrita." At that time "M" wrote to me letters au- thorizing me to edit and publish the English translation of his notes, and sent me the manuscript in English which he himself trans- lated, together with a true copy of a personal vii PREFACE letter * which Swami Vivekananda wrote to him. At the request of "M" I have edited and remodelled the larger portion of his English manuscript; while the remaining portions I " * Swami Vivekananda's letter to "M. -

The Viṣṇu Purāṇa ANCIENT ANNALS of the GOD with LOTUS EYES

The Viṣṇu Purāṇa ANCIENT ANNALS OF THE GOD WITH LOTUS EYES The Viṣṇu Purāṇa ANCIENT ANNALS OF THE GOD WITH LOTUS EYES Translated from the Sanskrit by McComas Taylor For my grandchildren Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] Available to download for free at press.anu.edu.au ISBN (print): 9781760464400 ISBN (online): 9781760464417 WorldCat (print): 1247155624 WorldCat (online): 1247154847 DOI: 10.22459/VP.2021 This title is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). The full licence terms are available at creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode Cover design and layout by ANU Press Cover image: Vishnu Reclining on Ananta. From Sage Markandeya’s Ashram and the Milky Ocean, c. 1780–1790. Mehrangarh Museum Trust. This edition © 2021 ANU Press Contents Preface xi Acknowledgements xiii Glossary xv Introduction 1 The purāṇas 1 The Viṣṇu Purāṇa 3 Problems with dating 4 Authorship 6 The audience 6 Relationship to other texts 7 The nature of Viṣṇu 10 Viṣṇu and Kṛṣṇa 12 The other avatāras 13 The purāṇic thought-world 14 Divine and semi-divine beings 18 Elements of the Viṣṇu Purāṇa 21 The six books 25 The Sanskrit text 32 Other translations 33 About this translation 34 References 38 Book One: Creation 43 1. Maitreya asks Parāśara about the world 43 2. Parāśara praises Viṣṇu; Creation 45 3. The divisions of time 50 4. Brahmā creates the world anew 52 5. Brahmā creates living beings 57 6. -

Ramayana: a Divine Drama Actors in the Divine Play As Scripted by Bhagawan Sri Sathya Sai Baba

Ramayana: A Divine Drama Actors in the Divine Play as scripted by Bhagawan Sri Sathya Sai Baba Volume III Compiled by Tumuluru Krishna Murty Edited by Desaraju Sri Sai Lakshmi © Tumuluru Krishna Murty ‘Anasuya’ C-66 Durgabai Deshmukh Colony Ahobil Mutt Road Hyderabad 500007 Ph: +91 (40) 2742 7083/ 8904 Typeset and formatted by: Desaraju Sri Sai Lakshmi Cover Designed by: Insty Print 2B, Ganesh Chandra Avenue Kolkata - 700013 Website: www.instyprint.in VOLUME III Na Karmana Na Prajaya Dhanena Thyagenaikena Amrutatthwamanasu (immortality is not attained through action, progeny or wealth. It is attained only by sacrifice). The bliss that you get out of sacrifice is eternal. That alone is the true wealth, and it can never diminish. In order to acquire such everlasting wealth, spend your time in the contemplation of God. Divinity pervades all that you see, hear and feel. Being in the constant company of such an all-pervasive Divinity, why should you worry and fear? Why fear when I am here? Never be afraid of anything; because God is in you, with you, above you, below you, around you. He follows you like shadow. Never forget Him. If you have faith, God will protect you wherever you are: in a forest or in the sky; in a city or a village; on a hill or in the middle of deep sea. All belong to Me and I belong to you all. Do not entertain any doubt or weakness. I am ready to give whatever you require. Be courageous. Why fear when I am here? Why should one fear when God has given such an assurance? If you follow Him, He will certainly bestow on you pure and unsullied bliss.