Valmiki Jayanti As a Socio-Cultural Performance In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Viral Research & Diagnostic Laboratories (VRDL), Department

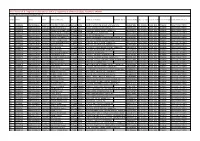

Viral Research & Diagnostic Laboratories (VRDL), Department of Microbiology, KCGMCH, KARNAL COVID Reports are available at kcgmc.edu.in Sr. No LAB ID SRF ID UHID NAME OF PATIENT AGE SEX ADDRESS OF PATIENT QUARANTINE AT CONTACT NUMBERDATE OF SAMPLEDATE RECEIVING OF REPORTINGPLACE OF SAMPLINGCOVID REPORT STATUS 1 KC402656 606700328611 1322711 RAVINDER MANDHAN (India)33 Years Male NEAR EX SARPANCH HOUSE, SAMALKHA Pin: 8168497900 03-05-2021 03-05-2021 KCGMCH NEGATIVE BY RTPCR 2 KC402658 606700328624 1153128 JASBIR SINGH (India) 35 Years Male H NO 8, ANAND COLONY, KARNAL Pin: 7988762425 03-05-2021 03-05-2021 KCGMCH NEGATIVE BY RTPCR 3 KC402659 606700328113 1190289 SAJJAN CHAUDHARY (India)26 Years Male KR HOUSE, MEERUT ROAD, KARNAL Pin: 9416008555 03-05-2021 03-05-2021 KCGMCH NEGATIVE BY RTPCR 4 KC402660 606700328629 1322722 DEEPAK ROHILLA (India) 35 Years Male H NO 598, SEC 4 ,KARNAL Pin: 9253751923 03-05-2021 03-05-2021 KCGMCH NEGATIVE BY RTPCR 5 KC402661 606700328639 1195592 RAKESH KUMAR (India) 40 Years Male 23, SEC 32, KARNAL Pin: 9812050003 03-05-2021 03-05-2021 KCGMCH NEGATIVE BY RTPCR 6 KC402662 606700328635 1322723 SHIV RAJ ACHARIYA (India)30 Years Male SASTRI NAGAR,NEAR MATA MANDIR, KARNAL Pin: 8375959950 03-05-2021 03-05-2021 KCGMCH NEGATIVE BY RTPCR 7 KC402663 606700328651 1322724 BHARAT SINGH (India) 53 Years Male CENTURY PLYWOOD, GANGER RAMBA ROAD, TARAORI9996712825 KARNAL Pin: 03-05-2021 03-05-2021 KCGMCH NEGATIVE BY RTPCR 8 KC402666 606700328678 1322727 SATYA NARAYAN (India) 75 Years Male H NO 201, MODEL TOWN, KARNAL Pin: 9215534567 -

Containment Zones

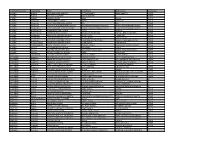

As on 4-June Containment Zones as identified by Ward level MOHs & Teams | @MyBMC | For updates, pl visit http://StopCoronavirusMCGMGovIn/insights-on-map *This is a revised list post rationlisation and reorganisation of earlier CZs for better utilisation of manpower and more effective containement Kindly refer the notes mentioned on the website Also, reach out to your respective Ward's teams in case of any discrepency for them to help update Ward # Pincode Address A 1 400001 M.R.A. Police Quarters,M.R.A. Road,Fort A 2 400001 M.R.A. Bmc Colony,M.R.A. Road,Fort A 3 400001 Ramgad Vasahat Zopadpatti,P D'Mello Road,Near St George Hospital,Fort A 4 400001 Servant Quarters, Cama Hospital,Mahapalika Marg,Fort A 5 400005 Sunder Nagari,Azad Nagari, Darya Nagar,Lala Nigam Road, Near Colaba Market,Sunder Nagar,Colaba A 6 400005 Machchimar Nagar,Capt. Prakash Pethe Marg,Colaba A 7 400005 Ganeshmurti Nagar Part No.1,2,3,Captain Prakash Pethe Marg,Ganeshmurthi Nagar,Colaba A 8 400005 Shivshakti Nagar, Garib Janata Nagar, Mahatma Phule Nagar,Capt. Prakash Pethe Marg,Colaba A 9 400005 Ambedkar Nagar,Capt. Prakash Pethe Marg,Colaba A 10 400005 Geeta Nagar,Dr Homi Bhabha Road,Near Navy Nagar,Colaba A 11 400005 Narayan Chawl 13, First Koli Lane,Rajwadkar Street,Colaba A 12 400005 7 Kashinath House, 5Th Koli Lane,Lala Nigam Road,Colaba A 13 400005 Meherzin Building,Sbs Road,Colaba B 14 400003 Cement Chawl No. 1,Madhavrao Rokade Road,Masjid Bunder Railway Station,Mandvi B 15 400003 Chatal Chawl,Sant Tukaram Road,Ahmadabad Street,Masjid Bunder B 16 400003 Hutment,1St Clive Road,Near Ashok Hotel,Masjid Bunder B 17 400003 Cement Chawl No. -

Cradle Tales of Hinduism Bv the Same Author, Footfalls of Indian History

NY PUBLIC LIBRARY THE BRANCH LIBRARIES 3 3333 07251 1310 Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2007 with funding from IVIicrosoft Corporation http://www.archive.org/details/cradletalesofhinOOnive CRADLE TALES OF HINDUISM BV THE SAME AUTHOR, FOOTFALLS OF INDIAN HISTORY. With 6 Coloured Plates and 22 other Illustra- tions. Extra crown 8vo, "Js. 6d. net ; 2 R. 8 as. AN INDIAN STUDY OF LOVE AND DEATH. Crown Svo, 2s. 6d. net. THE MASTER AS I SAW HIM. Being Pages from the Life of the Swami Vivekananda. Crown 8vo, 5s. net. STUDIES FROM AN EASTERN HOME. With a Portrait, Prefatory Memoir by S. K. Ratcliffe, and Appreciations from Professor Patrick Geddes, Professor T. K. Cheyne, Mr. H. W. Nevinson, and Mr. Rabindranath Tagore. Crown 8vo, 3J, 6d. net ; i R. 4 as. RELIGION AND DHARMA. Crown 8vo, 3^^. net ; I R. 4 as. This is a book on the Religion of Hinduism, its aims, ideals, and meaning. It appeals especially to those who are students of native life and Religion in India, and particularly to those who have some knowledge of the new movements in thought, art, and religion which are arising among the Indian natives. LONGMANS, GREEN AND CO. BOMBAY, CALCUTTA, AND MADRAS LONDON AND NEW YORK The Indian Story Teller at NigKtfall CRADLE TALES OF HINDUISM BY THE SISTER NIVEDITA (MARGARET E. NOBLE) AUTHOR OF "the WEB OF INDIAN LIFE," ETC. WITH FRONTISPIECE NE'i^r IMPRESSION LONGMANS, GREEN AND CO. HORNBY ROAD, BOMBAY 6 OLD COURT HOUSE STREET, CALCUTTA 167 MOUNT ROAD, MADRAS LONDON AND NEW YORK 1917 All rights reserved v) THE NEW YORK PUBLIC LIRHARY ASTw^, L6NOX AN» T<LDeN FOUNDaTIONI. -

Breaking Free: Reflections on Stereotypes in South Asian History

BREAKING FREE Reflections on Stereotypes in South Asian History By Edith B. Lubeck or many students, regardless of age or educational background, the . while curried aromas study of South Asian history seems a daunting task given the com- and vivid textiles enrich F plex and often unfamiliar nature of the subjects under investigation. the learning environment, Of course, exotic and stereotypic images of snake charmers and mystics abound. It is often tempting to rely on mnemonically convenient formulae images of wandering (caste defined and held as a constant, a given, over millennia) as the basis mystics, snake charmers, for instruction to reduce this material to manageable proportions. Although fatalistic villagers, timeless cultural “sound bites” may be easier for the secondary school student to digest when time constraints are great and the area of study is so disconcert- and immutable caste ingly new, the risks far outweigh the benefits. The best intentions of the his- structures and religious tory classroom are undone as historical time is compressed and dynamic modes of human interaction are reduced to a flat, two-dimensional plane. hatreds leave little Threats against Muslims and Muslim-owned property in the aftermath of the room for contextualized attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon have made crystal clear investigation in the study the importance of teaching the dangers of cultural stereotyping. In the article that follows I scrutinize those paradigms that continue to of South Asian history. hold a place of privilege in many textbooks despite fresh new research from numerous scholars working within the field of South Asian history over the past two decades. -

Ujjwal Siddapur.Pdf

GramPanchayatName TownName Name FatherName Mothername CasteGroup NILKUND Hallibail MANGALA SUBBA MARATTI VITTALA MARATTI GIRIJA MARATTI OTHER NILKUND Hallibail SHIVI SHIVU MARATTI BADIYA MARATTI OTHER NILKUND Hallibail yamuna.s. -

1. LETTER to WANDA DYNOWSKA Your Letter. You Are Suspicious

1. LETTER TO WANDA DYNOWSKA NEW DELHI, July 7, 1947 MY DEAR UMA, Your letter. You are suspicious. Sardar is not so bad as you imagine. He has no anti-European prejudice. Don’t be sentimental but deal with cold facts and you will succeed. My movement is uncertain. You will come when I am fixed up somewhere. Love. BAPU From a copy: Pyarelal Papers, Courtesy: Pyarelal 2. LETTER TO DR. D. P. GUPTA NEW DELHI, July 7, 1947 DEAR DR. GUPTA, Your letter.1 Faith to be faith stands all trials and thanks God. Are not the prayers of your Muslim neighbours sufficient encoura- gement for you to persist in well-doings? Yours sincerely, M. K. GANDHI From a photostat: C. W. 10570 1 The addressee, whose son had suffered injuries at the hands of Muslim rioters, had written that he could no longer have any faith in the doctrine of winning one’s enemy by love notwithstanding the sympathetic attitude of Muslim neighbours who prayed for his son’s recovery. VOL. 96 : 7 JULY, 1947 - 26 SEPTEMBER, 1947 1 3. LETTER TO ABDUL GHAFFAR KHAN [July 7, 1947]1 DEAR BADSHAH, No news from you. I hope you had my long letter and that you have acted up to it. Your and my honour is involved in strict adherence to non-violence on our part in thought, work and deed. No news up to now (9.30) in the papers.2 Love. BAPU Mahatma Gandhi—The Last Phase, Vol. II, pp. 279–80 4. MESSAGE TO KINDERGARTEN SCHOOL July 7, 1947 Are all the Bal Mandirs which are coming up these days worthy of the name? This is a question to be considered by all who are interested in children’s. -

EC 11A Designated Location Identity

Print ANNEXURE 5.11 (CHAPTER V, PARA 25) FORM -EC 11A Designated location identity (where List of applications for transposition of entry in Revision identity applications have been electoral roll Received in Form - 8A received) Constituency (Assembly /£THANESAR) @ 2. Period of receipt of applications (covered in this From To 1. List number list) date 16/11/2020 date 16/11/2020 3. Place of hearing* Details of person whose entry is to be transposed Details of Name of Serial applicant Part/Serial person number§ Date of (As given no. of roll Present place of Date/Time of whose of receipt in Part V in which EPIC No. ordinary hearing* entry is to application of Form name is residence be 8A) included transposed NEAR SAINI SCHOOL KULDEEP KULDEEP ,AKASH NAGAR 1 16/11/2020 SINGH SINGH 40 / 1109 AXO1137728 ,THANESAR BADWER BADWER ,KURUKSHETRA ,, KURUKSHETRA £ In case of Union Territories having no Legislative Assembly and the State of Jammu & Date of exhibition at Date of exhibition at Electoral Kashmir designated location under Registration Officer’s Office under @ For this revision for this designated location rule 15(b) rule 16(b) * Place, time and date of hearing as fixed by electoral registration officer § Running serial number is to be maintained for 27/11/2020 each revision for each designated location Print ANNEXURE 5.11 (CHAPTER V, PARA 25) FORM -EC 11A Designated location identity (where List of applications for transposition of entry in Revision identity applications have been electoral roll Received in Form - 8A received) Constituency (Assembly /£THANESAR) @ 2. Period of receipt of applications (covered in From To 1. -

Party Activity for Delhi Election 2015 District East on 01.02.2015

PARTY ACTIVITY FOR DELHI ELECTION 2015 DISTRICT EAST ON 01.02.2015 Name of Party AC Name BJP SAD BSP S. No. Particular INC AAP and No. (Bhartiya Janta (Sriomani Akali (Bahujan Samaj Other (Indian National Congress) (Aam Admi Party) Party) Dal) Party) Loudspeaker on auto No. DL 1 Public Type of Jan sabha with Jan sabha with RP 1460 three Wheeler - - meeting with programme Loudspeaker loudspeaker - DL 1 RM 5272 three Wheeler loudspeaker- All area Trilok puri AC 55 PS -27, block bus Bas stand of 27 Kalyan Puri, Mayur Vihar, 31/411 trilock puri, PS- stand Trilok Venue block trilok puri, - - New Ashok Nagar and Pandav Mayur vihar - puri ps ps mayor vihar Nagar mayor vihar 05:00 PM to 10:00 10.00 AM TO Time 08:00 AM to 08:00 PM -06.00 PM to 08.00 PM - - PM 1.30 PM- Loudspeaker on Bolero DL 1LT Pad yatra Type of Road show with 9768, Auto Rickshaw DlL 1 RN Pad yatra with - - with programme loudspeaker 7033 with Hoarding and 4 loudspeaker. loudspeaker Flags on each Vehicle All ac-55. Ps Bharti road All Vidhan Sabha AC 55 Trilok kalian puri new block-b new Puri PS Kalyan Puri, New 23/495,trilok puri, PS- Venue ashok nagar, - - ashok nagar Ashok Nagar, Mayur Vihar kalyan puri mayor vihar , PS new ashok and Pandav Nagar pandav nagar, nagar 08.00 AM to 11.00 AM to 55- Time 09:00 AM to 09:00 PM 03.00 PM to 05.00 PM - - 1. 10.00 PM 05.00 PM TRILOKPURI Type of Public meeting Pad Yatra with, Hand Mike, - - - - programme with loudspeaker Hand Bill, Flag, with Bharn Pal 17 blok in front Pocket 5 Gurdwra. -

Details of District East (Thane Wise)

ANNEXURE- VIII DETAILS OF DISTRICT EAST (THANE WISE) Source of Information- Police Stations LAXMI NAGAR LIST OF RESIDENT WELFARE ASSOCIATION AND MARKET ASSOCIATION OF P.S. LAXMI NAGAR RWA’s, D-BLOCK LAXMI NAGAR- 2. 3.1. AJAY GUPTA PRESIDENT 9890206083 4. ANIL K. THAKUR SECRETARY 8130353574 5. SUKHDAYAL SINGH JT. SECRETARY 6. MANOJ GUPTA TREASURER 7. PARAMJEET SINGH EXCEUTIVE MEMBER 8. HARMOHAN GOEL -DO- SATISH KUMAR -DO- MANOJ GEORGE, ADV. ADVISOR RWA’s, J&K EXT., LAXMI NAGAR:- 1. 2. 3. VINOD GUPTA PRESIDENT 9810401989 R.B. AGGARWAL VICE PRESIDENT 9818286617 R.P. SAXENA GENERAL SECRETARY 9911236880 RWA, J&K BLOCK, LAXMI NAGAR:- 2. 3.1. VED BHUSHAN SHARMA PRESIDENT 9810059237 SATISH GARG VICE PRESIDENT 9810401695 R.P. SAXENA GENERAL SECRETARY 9911236880 RWA, LALITA PARK, LAXMI NAGAR:- 1. 2. INDRAJEET PRESIDENT 9250326388 SATISH SHUKLA VICE PRESIDENT RWA, NARAYAN NAGAR, LAXMI NAGAR:- 1. SIRAJ PRESIDENT 9205543011239 | P a g e 2. ANIL CHOUHAN VICE PRESIDENT 9873646600 RWA, BANK ENCLAVE, LAXMI NAGAR:- 1. 2. 3. PADAM SINGH CH. PRESIDENT 9899300048 4. J.D. BAJAJ VICE PRESIDENT 9868207752 5. S.P. HANDA SECRETARY 9350390359 6. T.C. VERMA GENERAL SECRETARY 9818134631 K.L. GROVER MEMBER 9910210341 S.K. KAPOOR MEMBER 9818328484 RWA, E-BLOCK, JAWAHAR PARK, LAXMI NAGAR:- 1. 2. 3. RAMESH KAPOOR PRESIDENT 9810305015 KRISHNA KUMAR VICE PRESIDENT 9899036500 RAVINDER KUMAR GENERAL SECRETARY 8800549213 RWA, F-BLOCK, MANGAL BAZAR, LAXMI NAGAR:- 1. 2. 3. N.N. CHOUDHARY PRESIDENT 7292054537 MISRI LAL VICE PRESIDENT 8447570399 MAHESH CHAND NIGAM GENERAL SECRETARY 9990986362 RWA, WEST GURU ANGAD NAGAR, LAXMI NAGAR:- 1. 2. JAGJEET SINGH PRESIDENT 9910055483 DARSHAN SINGH VICE PRESIDENT 7678388857 RWA, RAMESH PARK, LAXMI NAGAR:- 1. -

List of Location of Aadhar Based Biometric Machine Installed Sr No

List of Location of Aadhar Based Biometric Machine Installed Sr No. DEVICE_ID LOC_NAME ENTRY_NAME 1 135710 AUTOWORKSHOP LAXMI BAI NAGAR Auto WorkShop Laxmi Bai Nagar (Device-1) 2 136119 AUTOWORKSHOP LAXMI BAI NAGAR DESKTOP BIOMETRIC AUTO WORKSHOP 3 101746 Aliganj Malaria Office 4 107131 Aliganj BMPK SERVICE CENTRE 5 124995 Aliganj Malaria Office 6 124298 Ansari Nagar, New Delhi NP CO-ED Sr. Sec. School, Ansari Nagar 03 7 135692 Ansari Nagar, New Delhi NP CO-ED Sr. Sec. School, Ansari Nagar 01 8 135693 Ansari Nagar, New Delhi NP CO-ED Sr. Sec. School, Ansari Nagar 02 9 117395 Aurangzeb Lane Aurangzeb Lane Dispensary 10 133466 Aurangzeb Lane Kiosk N.P. Coed Sr Sec School, Aurangzeb Lane 11 133477 Aurangzeb Lane Kiosk N.P. Primary School, Aurangzeb Lane 12 107173 Babar Road DISPENSARY NDMC BABAR ROAD 13 125798 Babar Road N.P Co-Ed Sec. School,Babar Road, New Delhi 14 131360 Babar Road NDMC PUBLIC LIBRARY 15 133949 Babar Road N.P Co-Ed Sec. School,Babar Road, New Delhi 16 133970 Babar Road NP PRIMARY SCHOOL NO 3 BABAR ROAD 17 135556 Babar Road N.P Co-Ed Sec. School,Babar Road, New Delhi 18 125095 Balmiki Basti N.P. Girls Sec School 01, Balmiki Basti 19 135831 Bangla Sahib Road ROAD SERVICE CENTRE TT PARK 20 107568 Bapu Dham DISPENSARY NDMC BAPU DHAM 21 128415 Bapu Dham DISPENSARY NDMC BAPU DHAM 22 135894 Bapu Dham Kiosk 2 NP Coed Sr Sec School 23 135897 Bapu Dham Kiosk 1 NP Coed Sr Sec School 24 112664 Barakhamba Road ZONAL OFFICE FIREBRIGADE LANE 25 135632 Barakhamba Road ZONAL OFFICE FIREBRIGADE LANE 26 096280 Bhagwan Das Road Circle No.14 Bhagwan Dass Road 27 125838 Bhagwan Das Road N.P Co-Ed Sec. -

List of Provisionally Accepted Applications for the Post of Peon

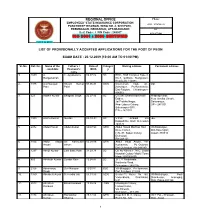

REGIONAL OFFICE Phone: EMPLOYEES’ STATE INSURANCE CORPORATION 0135 – 2774762 / 63 PANCHDEEP BHAWAN, WING NO. 4, SHIVPURI, PREMNAGAR, DEHRADUN, UTTARAKHAND Fax Beat Code : I PIN Code : 248007 0135-2771542 ISO 9001 : 2000 CERTIFIED CHINTA SE MUKTI LIST OF PROVISIONALLY ACCEPTED APPLICATIONS FOR THE POST OF PEON EXAM DATE : 20.12.2009 (10:00 AM TO 01:00 PM) Sl. No. Ref. No. Name of the Father’s / Date of Categor Mailing address Permanent address candidate Husband’s Birth y name 1. 1859 A. C. Ayyaswamy 06.07.82 SC ESIC, Staff Complex Type-3, Ranganathan No-7, O-Block, Mangolpuri, New Delhi-110083 2. 1375 A.D.Narayan Shyam Kumar 01.06.83 GEN. C/o-Hetram Naik, AT- DO Patel Patel jhanakpur, Po-Baramkela, Dist-Raigarh, Chhattisgarh- 496551 3. 323 Aadhin Kumar Bhagwat Singh 20.07.86 SC C/o Shri Dharmendra Nath Pradeep Vihar, Dubey, Near Gavlira Chowk, Jai Prabha Nagar, Saharanpur, Near Labour Colony, UP – 247 001 Saharanpur (UP), PIN – 247 001 4. 1995 Aashu Kumar Gurdas 08-10-84 SC V.P.O. Ambadi Via -do- Dakpaththa Distt Dehradun 248125 5. 2072 Abdul Hamid Abdul shukur 08/07/90 GEN Abdul Hamid Marfhan Havi Vill-Barkanpur, Deve Camuli, Dist-Karemganj H.N.-97, Saken Colony, Assam-788810 Dehradun Pin-248121 6. 1104 Abdul Majid Sri Kalimullah 05.08.89 GEN Abdul Majid Ansari, Vill- Ansari Ansari Kurkawala, Po.-Doiwala, Dist-Dehradun, Pin-248140 7. 1297 Abhijit Kumar Late Babu Ram 31.03.78 SC Qtr.No-Reena F 7N.C, Jindal Hospital Colony Model Town Hisar-125005(H.R) 8. -

THE OPEN COURT. the Nature of Science Is the Economy of Thought

The Open Court A. WEEKLY JOURNAIi Devoted to the Work of Conciliating Religion with Science, Entered at the Chicago Post-Ofl&ce as Second-Class Matter. -OFFICE, 169—175 LA SALLE STREET.- ( Dollars per Year. Vol. III.— 12 Two No. 90. CHICAGO, MAY 16, li Single Copies, I 10 cts. CONTENTS: RISE OF THE PEOPLE OF ISRAEL. I. Prof. Carl POETRY. Heinrich Cornill i6ig Sonnet. Louis Belrose, Jr 1626 FACTS AND TRUTHS. COL. INGERSOLL'S SCIENCE. To The Soul. W. D. Lighthall 1626 W, M. Boucher 1620 CORRESPONDENCE. THE SITAHARANAM ; OR, THE RAPE OF SITA. An Positivism. Louis Belrose, Jr 1626 Episode from the Great Sanskrit Epic "Ramayana." Comtists And Agnostics. R. F. Smith 1626 Prof, .\lbert H. Gunlogsen 1622 Philosophy At Montreal. JIarv Morgan (Gowan Lea.) 1627 THE COMING RELIGION. Charles K. Whipple 1623 Absolute Existence (^With Editorial Note). P 1627 GOD, FREEDOM, AND IMMORTALITY. Editor 1625 FICTION. BOOK REVIEWS, NOTES, ETC. The Lost Manuscript. (Continued.) Gustav Freytag. 1628 the con- REMINGTON TWENTIETHCENTURY ENLARGED AND IMPROVED. Devoted to Secular Religion dnd "THE WEEK," Social Regeneration. Type- A Cafiadian Journal of Politics^ Lit- erature^ Science J and Art. HUGH 0. PENTECOST, Editor. Published every Friday. $3.00 per writer year. $1.00 for Four Months. Contains, besides crisp and pointed editorials WON THE WEEK has entered on its SIXTHf^ear of and contributions from a corps of able writers, the publication, greatly enlarged and improved in every respect, rendering it still more worthy Sunday Addresses of the Editor before Unity Con- the cordial GOLD MEDAL support of every one interested in the maintenance gregation.