2004 Community Development Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mount Holyoke Range Planning Unit

Massachusetts Department of Conservation and Recreation Bureau of Planning and Resource Protection Resource Management Planning Program RESOURCE MANAGEMENT PLAN Mount Holyoke Range Planning Unit Including Mount Holyoke Range State Park, Joseph Allen Skinner State Park, Mount Tom State Reservation and Holyoke Heritage State Park July 2013 Mount Holyoke Range Planning Unit Including Mount Holyoke Range State Park, Joseph Allen Skinner State Park, Mount Tom State Reservation and Holyoke Heritage State Park RESOURCE MANAGEMENT PLAN 2013 Deval L. Patrick, Governor Richard K. Sullivan, Jr., Secretary John P. Murray, Commissioner Resource Management Plans provide guidance for managing properties under the stewardship of the Department of Conservation and Recreation (DCR). They are intended to be working documents for setting priorities, enabling the Department to adapt to changing fiscal, social and environmental conditions. The planning process provides a forum for communication and cooperation with park visitors and the surrounding communities to ensure transparency in the DCR’s stewardship efforts. As I travel the Commonwealth, I am reminded of the variety of high-quality experiences offered by DCR parks. Those within the Mount Holyoke Range Planning Unit are among the best that this state has to offer. They provide a variety of recreational opportunities, from challenging hikes along mountain ridgelines, to family picnics on a promontory overlooking the Connecticut River Valley, to taking in a summer concert in downtown Holyoke. Although they may all be visited in a single day, the true character of these parks is best revealed through repeat visits. In addition to providing outstanding recreational opportunities, these parks protect important natural and cultural resources. -

THE VINE Summer 2012 News from Wistariahurst Museum

Volume 7 Issue 3 THE VINE Summer 2012 News from Wistariahurst Museum The Skinner Legacy Tour The Skinner Family are famed nearly as much for their philanthropic gifts as they are for business innovation and expertise in producing high quality silk and satin fabrics. In the tradition of late 19th century industrialists, much of the money the family made in business was returned to the community as donations to support the construction and development of various institutions—a chapel, a hospital, a city library, a gymnasium, a coffee house and even a state park. Join the curators of Wistariahurst and the Joseph Allen Skinner Museum for a jaunt around Holyoke and South Hadley to learn more about how their endeavors in industry and philanthropy overlapped. The program includes transportation and tours of various Skinner venues. Participants will get an insider tour of the Skinner Chapel of the United Photo courtesy of Wistariahurst Congregational Church to see the beautiful stained glass windows and William Cobbet Skinner learn of the dedication of the chapel. The Joseph A. Skinner Museum will offer a tour of the eclectic collection featuring more than 6,000 objects and a special exhibition highlighting the collecting life of Joseph Skinner. The tour will include a stop at the Orchards, a former home of Joseph Skinner and his family in South Hadley. While in town, the group will also visit the Orchards Golf Course, host of the 2004 U.S. Women’s Open. Founding Director of the Donald Ross Society, Michael Fay, will present “20 Minutes with Donald Ross” dressed in plus‐fours, and refreshments can be enjoyed on the deck of the clubhouse. -

Open Space, Recreation, and Multi-Use Trail Plan (2018-2025)

Open Space, Recreation & Multi-Use Trail Plan (2018-2025) Open Space, Recreation, and Multi-Use Trail Plan This plan is Northampton’s vision and blueprint for open space, recreation and multiuse trails. It is consistent with broader city goals for quality of life, vibrant urban centers, and sustainable and resilient community. The plan is consistent with the Sustainable Northampton Comprehensive Plan (2008), the City’s duly adopted comprehensive plan, and has been adopted as an additional component of that plan. For information on related projects, visit Planning & Sustainability at www.northamptonma.gov/plan. Plan Adopted or Endorsed by 7 City boards Planning Board (June 14, 2018) adopted as part of the city’s comprehensive plan Conservation Commission (June 14, 2018) Parks and Recreation Commission (June 5, 2018) Historical Commission (April 30, 2018) Transportation & Parking Commission (April 11, 2018) Bicycle and Pedestrian Subcommittee (March 21, 2018) Agriculture Commission (April 24, 2018) Plan Approved by the Commonwealth of Massachusetts Executive Office of Energy and Environmental Affairs (August 31, 2018) Staff Wayne Feiden, FAICP, Director of Planning & Sustainability (project manager) Sarah LaValley, Conservation, Preservation, and Land Use Planner Carolyn Misch, AICP, Senior Land Use Planner Ann-Marie Moggio, Director of Parks and Recreation James Thompson, GIS Coordinator Table of Contents 1 Plan Summary 3 2 Introduction 4 3 Community Setting 5 4 Environmental Inventory and Analysis 18 5 Conservation and Recreation Inventory 33 6 Community Vision 99 7 Analysis of Needs 100 8 Goals and Objectives 102 9 Seven-Year Action Plan 108 10 Public Comments 118 11 References 120 A ADA Self-Evaluation Report 121 1 Plan Summary Th e Open Space, Recreation and Multi-Use Trail Plan is Northampton’s vision and its blueprint for using its resources to meet the City’s open space, agriculture, conservation, multi-use trail, parks, and recreation needs. -

Designing for Climate Change Resilience

Designing for Climate Change Resilience con'text Magazine of The Conway School //2 01 7// Faculty Administration Mollie Babize ’84 Bruce Stedman ’78 Planning + Design Executive Director Ken Byrne Ken Byrne Humanities Academic Director Anne Capra ’00 Dave Nordstrom ’04 Planning Finance Director Kate Cholakis ’11 Nancy Braxton Landscape Planning + Alum Coordinator Design Kate Cholakis ’11 Kim Erslev Admissions Manager Landscape Design, Site Rachel Lindsay ’15 Engineering, Graphics Publications Manager CJ Lammers Priscilla Novitt ’07 Planning Senior Administrator Bill Lattrell Kristin Thomas ’10 Ecology Project Manager Rachel Loeffler Dave Weber ’15 Site Engineering + Campus Manager Landscape Design Elaine Williamson ’11 Glenn Motzkin Event Coordinator Ecology Jono Neiger ’03 Board of Trustees Regenerative Design Keith Ross, Chair Keith Zaltzberg LandVest Digital Design Warwick, MA Stephen Thor Johnson, Visiting Instructors Vice Chair + Clerk Michael Ben-Eli North American Land Trust Sustainability Chadds Ford, PA Walt Cudnohufsky Timothy A. Umbach, Design Process Treasurer Northampton, MA Edwina von Gal Landscape Architecture Mitch Anthony Clarity David Jacke ’84 Northampton, MA Permaculture Janet Curtis ’00 Erik van Lennep ’83 Union of Concerned Sustainability Scientists Climate Program John O’Keefe Cambridge, MA Ecology Marianne Jorgenson Keith Ross ALPINE Conservation Innovation Cambridge, MA Joel Russell Nicholas Filler Conservation Law Conway, MA Dana Tomlin John O’Keefe GIS Harvard Forest Petersham, MA Greg Watson Food Systems Theresa Sprague ’08 Ecological Landscape Alliance The Conway School Harwich, MA of Landscape Design 322 S. Deerfield Road Charles Tracy PO Box 179 US National Park Service Conway, MA 01341-0179 Boston, MA 180 Pleasant St. Studio 211 William B. Sayre Easthampton, MA 01027 Wm. -

Appendix A. Plan Contributors

Appendix A. Plan Contributors. Name Affiliation Area of Expertise Department of Conservation and Recreation Berkland, Ellen Office of Cultural Resources Archaeological resources Brazeau, Rich Bureau of Engineering Infrastructure Brown, Stephen Bureau of Planning and Resource Protection Energy efficiency Carr, Robert A. Mount Tom State Reservation Park operations Carter, Jesse Mount Holyoke Complex Park operations Cavanagh, Paul RMP Program Natural resources planning Church, Peter Bureau of Forest Fire Control and Forestry Forest management Clark, Doug Connecticut River Greenway State Park Connecticut River GSP properties Fiesinger, Anne Office of External Affairs and Partnerships Outreach Fisher, Sean Archivist, Office of Cultural Resources Agency history Gieryk, Michael Management Forestry Program Forest ecology and management Goodwin, David Management Forestry Program GIS Greene, Judy Plans Archivist, Office of Cultural Resources Agency history Gregory, Paul Management Forestry Program CFI data tables Griffin, Dan Holyoke Heritage State Park Park operations Harris, Jeffrey Office of Cultural Resources Historic resources Howard, Jennifer Land Protection Program Land acquisition and protection Hunt, Daniel Director of Government Affairs Legislative relations Jahnige, Paul Greenways and Trails Program Recreation Lotspeich, Charlie Holyoke Heritage State Park Park operations Lowell, Rob Bureau of Engineering Storm water McCarthy, Tom Universal Access Program Universal access Mellace, Bob Regional Director Park operations Michaels, Peter -

Outlines of the Geology of Western Massachusetts

OUTLINES OF THE GEOLOGY OF WESTERN MASSACHUSETTS. TOPOGRAPHY. channels deeper. It is obvious that these exist details of fact which constitute the record are formations stand in their proper relative positions, ing conditions under which the plain is being described in the essay relating to each quadrangle. the oldest at the bottom. In order to follow this general description, destroyed are not those under which it was The greater portion of the rocks of the Green which is applicable to territory extending beyond formed. Mountains in Massachusetts were once horizontal ALGONKIAN PERIOD. the limits of the Holyoke quadrangle, Quadrangles To gain an idea of the manner of development beds of gravels, sands, clays, and marls, Origin of the In the usage adopted in this atlas the term the reader is referred to the following referred to- of the once level surface of the plateau, we may which became consolidated into con- rocks- "Archean" is applied to those most ancient crys topographic sheets of western Massachusetts: conceive the present process of gradual glomerates, sandstones, shales, and limestones. talline rocks which form part of the Greylock, Hawley, Greenfield, Becket, Chester wearing down carried to completion. They began to accumulate at a time remote in original crust of the earth and which ancient rocks 0 of this region, field, Northampton, Sandisfield, Granville, and When the streams shall have carved plateau- the geological past, when the region was invaded antedate and underlie the oldest sedi- Springfield, all on a scale of 1 mile to 1 inch. away the elevations now existing, the plateau by the sea. -

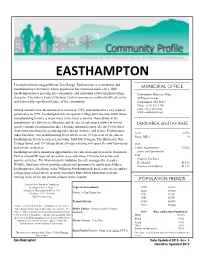

Easthampton Profile.Pdf

EASTHAMPTON Located below the rugged Mount Tom Range, Easthampton is a residential and MUNICIPAL OFFICE manufacturing community whose population has remained stable since 2000. Easthampton has a growing arts community, and maintains a New England village Easthampton Municipal Bldg. character. The town’s Central Business District remains an architecturally attractive 50 Payson Avenue and historically significant feature of the community. Easthampton, MA 01027 Phone: (413) 529-1470 Settled around 1664, incorporated as a town in 1785, and changed to a city form of FAX: (413) 529-1488 www.easthampton.org governance in 1996, Easthampton was an agrarian village until the mid-1800s when manufacturing became a major force in the local economy. Innovations in the manufacture of cloth-covered buttons and the use of vulcanized rubber in woven LAND AREA and TAX BASE goods catapulted Easthampton into a leading industrial center. By the 1900s, there were numerous factories producing yarn, thread, buttons, and elastic. Easthampton Acres 8,674 today has thirty-two manufacturing firms which create 19.3 percent of the jobs in Square Miles 14 Easthampton. Projects such as Eastworks, Mill 180, Paragon, The Brickyard, One Cottage Street, and 15 Cottage Street all reuse existing mill space for new businesses 2012 and private residences. Vehicle Registrations 15,602 Easthampton offers numerous opportunities for education and recreation. Nonotuck (autos and light trucks) Park is a beautiful regional recreation area containing 190 acres for active and 2015 passive activities. The Massachusetts Audubon Society manages the Arcadia Property Tax Rates Residential $15.15 Wildlife Sanctuary which provides educational programs for adults and children. -

Bulletin of the Massachusetts Archaeological Society, Vol. 70, No. 1 Massachusetts Archaeological Society

Bridgewater State University Virtual Commons - Bridgewater State University Bulletin of the Massachusetts Archaeological Journals and Campus Publications Society Spring 2009 Bulletin of the Massachusetts Archaeological Society, Vol. 70, No. 1 Massachusetts Archaeological Society Follow this and additional works at: http://vc.bridgew.edu/bmas Copyright © 2009 Massachusetts Archaeological Society This item is available as part of Virtual Commons, the open-access institutional repository of Bridgewater State University, Bridgewater, Massachusetts. BULLETIN OF THE MASSACHUSETTS ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETY VOLUME 70 (1) SPRING 2009 CONTENTS: Editor's Note. 1 In Memoriam: Thomas E. Lux Kathryn Fairbanks . 2 Fire Making Kits William B. Taylor 3 From Plow to Trowel, Concord's Dugans Brook Knoll Site Revealed. Martin G. Dudek 7 Mount Tom Cherts and Associated Lithics, Connecticut Valley, Massachusetts David Driver and Barbara Calogero . 29 A Stranger in My Field Donald Gammons.. 49 Contributors 51 THE MASSACHUSETTS ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETY, Inc. P. O. Box 700, Middleborough, Massachusetts 02346-0700 THE MASSACHUSETTS ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETY, Inc. Robbins Museum of Archaeology Web Site address: www.massarchaeology.org phone: (508) 947-9005 email: [email protected] Officers: Frederica Dimmick, 10 Sassamon Road, Natick, MA 01760 President Fred Robinson, 6 Christopher Drive, Greenville, RI 02828 Vice President Susan Jacobucci, 678 Chief Justice Cushing Highway, Scituate, MA 02066 Clerk Dan Lorraine, 63 Cranberry Terrace, Cranston, RI 02828 Treasurer Eugene Wmter, 54 Trull Lane, Lowell, MA 01852 Museum Coordinator Curtiss Hoffman, 58 Hilldale Road, Ashland, MA 01721 Bulletin Editor Jane Lopes, P.O. Box 1273, Middleborough MA 02346 Corresponding Secretary Tonya Largy, 59 Moore Road, Wayland, MA 01778 Past President Trustees: Term Expires Edwin C. -

Easthampton 2019 Housing Choice

EASTHAMPTON 2019 HOUSING CHOICE CAPITAL GRANT BIKE SHARE Bike Share Easthampton Introduction The primary objective of this funding is to allow the City of Easthampton to rapidly deploy bike share in conjunction with the recent launch of a bike share program in five nearby municipalities. We are requesting $250,000 for the creation of five bike share locations within the City and deploy approximately 36 new electric assist bike share bicycles. The funding will allow the City to become a member of the existing five town consortium and the regional ValleyBike Share Program. The grant will cover the full cost of all construction, docking equipment, bicycles, and wayfinding, and which can be completed by June 2019. Operating costs for the program will be funded through local and regional sponsorships in line with the program established through the existing vendor and existing ValleyBike share program. The funding will allow the City to deploy the following: 2 3 36 City of Easthampton – 2019 Housing Choice Capital Grant – Bike Share The communities of Amherst, Holyoke, Northampton, South Hadley, and Springfield, along with the University of Massachusetts and the Pioneer Valley Planning Commission have contracted a collaboration and partnership with Bewegen Technologies and Corps Logistics to bring bike share to our region. The Pioneer Valley’s program is designed to promote short bike trips within core communities, where clusters of large employers, colleges, shopping, tourist destinations and residents can readily be connected. The City of Easthampton is supported in this request by the City of Northampton (Mayor and Planning and Sustainability Director) who is the lead municipality for the ValleyBike Share program and the Greater Easthampton Chamber of Commerce. -

THE RANGE and RIVER

THE RANGE and RIVER : An Open Space and Recreation Plan for South Hadley, Massachusetts: 2007-2012 As Approved by the EOEEA on July 20, 2007 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS SECTION PAGE 1 PLAN SUMMARY 1 2 INTRODUCTION 2 2.1 Statement of Purpose 2 2.2 Planning Process and Public Participation 3 3 COMMUNITY SETTING 5 3.1 Regional Context 5 3.2 Historical Overview 8 3.3 Population Characteristics 12 3.4 Growth and Development Pattern 17 4 ENVIRONMENTAL INVENTORY AND ANALYSIS 28 4.1 Geology & Soils 28 4.2 Water Resources 33 4.3 Vegetation 36 4.4 Fisheries and Wildlife 41 4.5 Scenic Resources and Unique Environments 42 4.6 Environmental Problems 46 5 INVENTORY OF LANDS OF CONSERVATION AND RECREATION INTEREST 48 5.1 Agricultural Program Parcels 48 5.2 Conservation Restriction Parcels 49 5.3 Private Recreation Parcels 50 5.4 Public and Nonprofit Parcels 51 5.5 Other Significant Private Parcels 59 5.6 Utility Company Parcels 59 6 COMMUNITY GOALS 62 6.1 Description of Process 62 6.2 Statement of Open Space and Recreation Goals 63 7 ANALYSIS OF NEEDS 65 7.1 Summary of Resource Protection Needs 65 7.2 Summary of Parks and Facility Needs 66 7.3 Summary of Community Need 67 7.4 Management Needs, Potential Change of Use 69 8 GOALS AND OBJECTIVES 71 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS (CONT’D.) SECTION PAGE 9 FIVE-YEAR ACTION PLAN 74 9.1 Accomplishments 74 9.2 2007-2012 Five-Year Action Plan 75 10 PUBLIC COMMENTS after 76 11 REFERENCES 77 APPENDICES A Land Protection Methods A- 1 B Land Protection Programs A- 3 C The American Farmland Trust Cost of Community Services Study A- -

A Park Activities Program for Mount Tom Reservation. Robert P

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 1939 A park activities program for Mount Tom Reservation. Robert P. Hunter University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses Hunter, Robert P., "A park activities program for Mount Tom Reservation." (1939). Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014. 2594. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses/2594 This thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A PARK ACTIVITIES PROGRAM FOR MOUNT TOM RESERVATION by ROBERT P. HUNTER SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE MASSACHUSETTS STATE COLLEGE 1939 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION Page Need for Recreational Areas.• • 2-3 Statement of the Problem.••.•••••••••••••.•• 3 - 4 Significance of the Problem... 4 Limitations of the Problem. ... 4 Procedures. 5 BRIEF DESCRIPTION OF MOUNT TOM RESERVATION Location.. 6 Topographic Features... 7 The Land...... ♦ • .. 8 History.................. ..8-9 Administration of the Area..10 Existing Facilities.••••••••••••••..♦..«•...10 The C.C.C. Camp.... .11 PAST USE OF MOUNT TOM RESERVATION Attendance Table I - By Days of the Week.......12 Table II - By Age Groups...13 Table III - Car Tabulations..13 Table IV - Periods of the Day. ..»13 Table V - Weekly Percentages,..♦•♦•14 Program Prior to 1939#....♦♦••♦♦♦♦•••♦•14 PROGRAM FOR MOUNT TOM - 1939 Administration ......15 - 17 Chart 1 - Organization Advisory Committee 17 - 18 Leadership. 19 «• 33 Park Activities.. -

Outdoor Recreational Resources C H a P T E R 4

Connecticut River Scenic Byway Corridor Management Plan June 2016 Outdoor Recreational Resources C H A P T E R 4 Connecticut River Scenic Byway Introduction The Connecticut River Scenic Byway area has a wealth of outdoor recreational resources. There are activities for all seasons which create diverse opportunities for recreation. During the winter there are opportunities to cross-country ski and snowshoe, while spring provides warmer weather for hiking and biking. Summer is an excellent time to fish and paddle on the Connecticut River, and autumn provides opportunities to view the Byway’s spectacular foliage. This chapter details the outdoor recreational resources along the Byway, and discusses potential issues and concerns that could affect the quality of these resources over time. The chapter concludes with recommendations to protect, maintain, and enhance the Byway’s recreational resources. Resources located directly on or within a half-mile radius of the Connecticut River Scenic Byway are noted with this roadway symbol. While the Corridor Management Plan focuses on resources that are located within a half mile of the Connecticut River Scenic Byway, this chapter also includes recreational attractions that are outside of the study area boundary, but within the towns along the Byway. The activities at each site are shown in italics. Resources with recreational access for people of all abilities (universal access) are noted with this symbol. More information on sites with universal access is located on page 25. State Forests, Wildlife Management Areas, and Other Open Spaces Multiple Towns along the Byway Connecticut River Greenway State Park (Northfield, Sunderland, Hadley, South Hadley, and Hatfield) The Connecticut River Greenway is one of Massachusetts' newest State Parks.