Mediation in the Family Room

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PROGRAM November 18-20, 2015 THANKS to the 2015 Children, Youth & Media Conference Sponsors

Toronto PROGRAM November 18-20, 2015 THANKS tO tHe 2015 ChIlDrEn, YoUtH & MeDiA CoNfErEnCe sponsors MAIN SPONSOR PRESTIGE SPONSORS EXCELLENCE SPONSORS 2 SPECIAL THANKS Youth Media Alliance would like to warmly thank its 2015 Children, Youth & Media Conference advisory committee: NATALIE DUMOULIN / 9 Story Media Group MARTHA SEPULVEDA / RACHEL MARCUS / Guru Studio Breakthrough Entertainment MICHELLE MELANSON CUPERUS / CLAUDIA SICONDOLFO Radical Sheep Productions JULIE STALL / Portfolio Entertainment LYNN OLDERSHAW / Kids’ CBC TRAVIS WILLIAMS / Mercury Filmworks MIK PERLUS / marblemedia SUZANNE WILSON / TVO Kids JAMIE PIEKARZ / Corus Entertainment And the volunteers: KELLY LYNNE ASHTON, KAYLA LATHAM, HENRIKA LUONG, TATIANA MARQUES, JAYNA RAN and MARCELA LUCIA ROJAS. TABLE OF CONTENTS Words from Chair .............................................................................p. 4 Words from Executive Director ............................................................p. 5 Schedule and Venue ..........................................................................p. 6 General Conference ..........................................................................p. 8 Workshop with Sheena Macrae ............................................................p. 12 Workshop with Linda Schuyler .............................................................p. 12 Prix Jeunesse Screening ....................................................................p. 13 Speakers’ Biographies .......................................................................p. -

Free Online Johnny Test Racing Games

Free online johnny test racing games Play Johnny Test games to see what crazy experiment Johnny Test and his dog Dukey try next! Play lots of other free online games on Cartoon Network! Love Johnny Test? Play the latest Johnny Test games for free at Cartoon Network. Visit us for more free online games to play. Street Skate Race · Deep Sea. Play the free Johnny Test game, Street Skate Race and other Johnny Test games at Cartoon Network. Johnny Test? Play the latest Johnny Test games for free at Cartoon Network. Visit us for more free online games to play. Gravity Pants · Street Skate Race. Game Johnny Test: Road Race online. Johnny Test will take the most difficult route on your favorite vehicle - skateboard. It is well managed and. Homepage» Search results for: johnny test Johnny Test: Street Skate Race With an ever-expanding showcase of free online games, is. Play Johnny Test games to see what crazy experiment Johnny Test and his dog Dukey try next! Play lots of other free online games on Cartoon Network. The administrative team of has added 17 Johnny Test Games, . success among you kids, we thought it's time for a new adventure game with. here on , the best website with free online games of all types!!! Johnny Test · Cartoon. Johhny's sisters gave him a camera that he can use it underwater. He's very good at diving but this time he won't have his wet suit. Monday - Friday AM et/pt, Sundays at AM ET/PT, Monday - Friday at PM ET/PT. -

Download the Program

Sponsors Partners Special Thanks The Alliance for Children and Television (ACT) would like to warmly thank it’s Média-Jeunes 2010 advisory committee : Guillaume Aniorté Pierre Proulx Tribal Nova Alliance Numérique Marie-Claude Beauchamp Nancy Savard CarpeDiem Productions 10e Ave Marie-Hélène Guay Sylvie Tremblay Télé-Québec Productions Sovimage Marc Beaudet Turbulent Special thanks go to Louise Lantagne and Lisa Savard of Radio-Canada for housing the Alliance for Children and Television’s Offi ce free of charge. Special thanks as well to Kirsten Schneid, Organization Manager of the Munich PRIX JEUNESSE and to David W. Kleeman, Executive Director, American Center for Children and Media, for helping us with the screening of the Munich Prix Jeunesse. Many thanks to all our collaborators and volunteers. Summary Welcome note from ACT’s Director 3 Organization 4 A word from our Sponsors 5 Schedule – Conferences, November 18 9 The future of Quebec’s youth animation industry 10 How can we convey positive messages to young people through the various media platforms they use? 13 Exclusive Lunch with a Broadcaster 15 Is TV really dying? 16 Portrait of the Situation with the new CMF 18 Audience migration to new platforms: what are the challenges for public broadcasters? 19 Engaging kids and building communities around a TV brand 21 Schedule – Screenings, November 19 23 Welcome note from ACT’s Director Welcome to Média-Jeunes 2010! Here we are – creators, artists, producers, broadcasters, researchers and fi nancial backers – all together again to review our methods, expand our horizons, and discuss the latest issues. This year, we’re also taking the opportunity to unveil our new name, logo and mission statement! We are now in a world where content is increasingly delivered on new platforms, especially where kids are concerned, so the Alliance is giving itself a makeover to expand its efforts to all types of screens, not just TV. -

Johnny Test CYOA (Jumpchain-Compliant!) +1000 CP

Johnny Test CYOA (Jumpchain-Compliant!) You're not sure why your benefactor put you here, really. The animation is cheap and choppy, and you're pretty sure you don't actually like anyone here. That said, a world is a world, and with any luck, you can make an impact on this one. Of course, don't be surprised if some of your plans go a bit haywire. That's just another day in the life of a boy named Johnny Test. If you want to get anything out of this trip, you'll need these. +1000 CP Good luck, and have fun in Porkbelly! Or, at least try to. See, there's two last little provisions here. Should Johnny Test or any of his enemies or family members be slain, by your hand or any other, you will fail. This includes being trapped in permanent stasis or being permanently banished/barred from the “real world” of this dimension. There is, however, a certain limit to this – Bumper is fair game. Bling-Bling Boy, on the other hand, is not. The second? You know that time machine? Traveller! You can't do that! The future will be changed! You'll create a time paradox! Section 1: Background Roll 1d8+11 to determine your age and keep your current gender, or pay 50 CP to choose your age (within the rollable range) and gender for yourself. Drop-In [Free] – You don't have any new memories or new quirks here – but nobody here knows you, and at least some of them can tell there's something off about you.. -

Bronycan Con Book

1 Credits BronyCAN 2013 Visit BronyCAN.ca/Staff for the complete staff list! Con Chair Charity Auction Artists Jay “Regen” Weiland Nathan “Drake” Rogers Cas - catspian.deviantart.com Deer - deerghost.deviantart.com Irvin Durana - sonicpower451.deviantart.com Finance Registration & Vendors Keenan Born - kborn.deviantart.com Jason “HaloInverse” Brownridge William “Dexter Rabbit” Dixon Marco Paparatto - marco23p.deviantart.com Jon “Shroobs” Leslie Mareinthemoon - mare--in--the--moon.deviantart.com PonyHuman Resources Lorne “Gizmo” Seifred Radioactive K - radioactive-k-deviantart.com Silver Nicktail Alex “Afion” Ing Tatsuki - askrosequartz.tumblr.com Guest Relations Audio/Visual Apricity/Provincial Ponies Erin “Sharky” Leslie Kristie “Rabbitasaur” Bush Felyx “BeamPegasu5” Kain Zephaniah “Eclipse” Washington albinosharky.deviantart.com Andrew “adeptusraven“ Ho Sean “Shramp” Browning Kaelisa “MyLittlePonyTales” VanDyke Landon “Lupon” Freden stickgag.deviantart.com Sabrina “realafterglow” Taylor Marty “Ginge” Sisk Tabatha Hughes Jacob “GhostSonic” Poersch Amanda “CrimsonFirefal” Pyle Alex “Sumap” Schell Ask BronyCAN Randy Ho Aaron “Fisherpon” Siebenga Angela “Ponyzilla” Li Information Tech Wanderereclipse Jacob “GhostSonic” Poersch Thomas “Solar Flare” Sullivan Nick Nack Rebeckah “Misaki” MacLeod Richard “CascadeHope“ Layes Peter “Feld0” Deltchev Staff Photagrapher Public Relations Carson “Spitfire” Berreth Lucas “Senn555” Sestak Gophers and Grunts David “The Iron Pony” Cuyno Skyler “Time Right” Hoff-Male Original Founders Angela “Ponyzilla” -

NETFLIX – CATALOGO USA 20 Dicembre 2015 1. 009-1: the End Of

NETFLIX – CATALOGO USA 20 dicembre 2015 1. 009-1: The End of the Beginning (2013) , 85 imdb 2. 1,000 Times Good Night (2013) , 117 imdb 3. 1000 to 1: The Cory Weissman Story (2014) , 98 imdbAvailable in HD on your TV 4. 1001 Grams (2014) , 90 imdb 5. 100 Bloody Acres (2012) , 1hr 30m imdbAvailable in HD on your TV 6. 10.0 Earthquake (2014) , 87 imdb 7. 100 Ghost Street: Richard Speck (2012) , 1hr 23m imdbAvailable in HD on your TV 8. 100, The - Season 1 (2014) 4.3, 1 Season imdbClosed Captions: [ Available in HD on your TV 9. 100, The - Season 2 (2014) , 41 imdbAvailable in HD on your TV 10. 101 Dalmatians (1996) 3.6, 1hr 42m imdbClosed Captions: [ 11. 10 Questions for the Dalai Lama (2006) 3.9, 1hr 27m imdbClosed Captions: [ 12. 10 Rules for Sleeping Around (2013) , 1hr 34m imdbAvailable in HD on your TV 13. 11 Blocks (2015) , 78 imdb 14. 12/12/12 (2012) 2.4, 1hr 25m imdbClosed Captions: [ Available in HD on your TV 15. 12 Dates of Christmas (2011) 3.8, 1hr 26m imdbClosed Captions: [ Available in HD on your TV 16. 12 Horas 2 Minutos (2012) , 70 imdb 17. 12 Segundos (2013) , 85 imdb 18. 13 Assassins (2010) , 2hr 5m imdbAvailable in HD on your TV 19. 13 Going on 30 (2004) 3.5, 1hr 37m imdbClosed Captions: [ Available in HD on your TV 20. 13 Sins (2014) 3.6, 1hr 32m imdbClosed Captions: [ Available in HD on your TV 21. 14 Blades (2010) , 113 imdbAvailable in HD on your TV 22. -

UK Animation Industry Digs Deep in Tough Climate P36 a Look At

A look at opportunities in new UK animation industry digs Smarty Pants study reveals kids licensing hot spot Ukraine p11 deep in tough climate p36 trends to watch in 2012 p28 engaging the global children’s entertainment industry A publication of Brunico Communications Ltd. JANUARY 2012 CANADA POST AGREEMENT NUMBER 40050265 PRINTED IN CANADA USPS AFSM 100 Approved Polywrap CANADA POST AGREEMENT NUMBER 40050265 PRINTED IN USPS AFSM 100 Approved Inside January 2012 moves 7 Check out our complete list of Kidscreen Awards nominees! Hot Talent—Ben Bocquelet shares his inspiration for CN hit Gumball tv 15 A new US study proves TV rules while an app gap looms JustLaunched—Redakai courts next- gen fan boys through global rollout consumer products 24 A look inside the next Eastern European licensing hot spot—Ukraine Licensee Lowdown—Locutio pioneers in-car category with Sesame Workshop kid insight 28 Smarty Pants’ 2011 Young Love study reveals brands kids will flock to in 2012 Kaleidoscope—Nickelodeon takes a closer look at the lives of Millennials interactive 34 Is that an app or an eBook? Lines between digital products blur TechWatch—TRU’s Nabi Pad makes 23 entrée into kid-friendly tablet market Montreal, Canada-based Sardine Productions takes Chop Chop Ninja from gaming world to TV Rule Britannia? 36 Special Report The UK animation industry struggles to find its footing in a competitive global market Nick and Nielsen Teletoon refresh PBS Kids steps Cool or Not? Web subscription ready to rumble brings bounce up hunt for Moshi vs. service gets 73over ratings 18 to branding 26 promo partners 2Webkinz 35crafty for kids Cover Our international, event and domestic copies feature an ad for CGI-animated series The Garfield Show from Paris-based Mediatoon. -

Buenos Aires/Argentina

CONTENTS 40 28 12 FEATURES Case Study: J.J. Abrams DEPARTMENTS Bad Robot = Good Stories. 12 From the National Executive Director The Issue at Hand Not Just a Survivor 6 Mark Burnett’s leap into On Location scripted television. 28 78 Argentina/Buenos Aires Feeling Alright Going Green Tracey Edmonds channels 85 PGA Green Production Guide goes mobile positivity via YouTube. 40 PGA Bulletin Four More Years! 88 Looking back at the 52 Member Benefits Produced By Conference. 91 Vertical Integration Mentoring Matters Brian Falk at Morning Mentors The effects of related party deals 60 92 on profit participations. Sad But True Comix 94 Network Flow! PGA ProShow Your guide to the finalists. 69 Cover photo: Zade Rosenthal May – June 2013 3 producers guild of america President MARK GORDON Vice President, Motion Pictures GARY LUCCHESI Vice President, Television HAYMA “SCREECH” WASHINGTON Vice President, New Media CHRIS THOMES Vice President, AP Council REBECCA GRAHAM FORDE Vice President, PGA East PETER SARAF Treasurer LORI McCREARY SLEEP LIKE A Secretary of Record GALE ANNE HURD President Emeritus MARSHALL HERSKOVITZ National Executive Director VANCE VAN PETTEN Representative, BICOASTAL BABY. BRANDON GRANDE PGA Northwest Board of Directors DARLA K. ANDERSON INTRODUCING FLAT BEDS ON FRED BARON CAROLE BEAMS BRUCE COHEN SELECTED FLIGHTS TO JFK. MICHAEL DE LUCA TRACEY E. EDMONDS JAMES FINO TIM GIBBONS RICHARD GLADSTEIN GARY GOETZMAN Complete Film, TV and Commercial Production Services SARAH GREEN JENNIFER A. HAIRE VANESSA HAYES Shooting Locations RJ HUME -

Content Rules All Screens

® A PUBLICATION OF BRUNICO COMMUNICATIONS LTD. SUMMER 2013 PRODUCERS HONE DIGITAL STRATEGIES INDIE SURVEY SAYS... SPENDING RISING CONTENT RULES ALL SCREENS ALSO: EQUITY CROWDFUNDING | MUSE TURNS 15 | FILM SELF-DISTRIBUTION | PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT PPB.Cover.summer13.inddB.Cover.summer13.indd 3 114/05/134/05/13 55:33:33 PPMM PPB.23305.StudioUpstairs.inddB.23305.StudioUpstairs.indd 1 113-05-133-05-13 33:30:30 PPMM SUMMER 2013 table of contents Canadian director Ken Girotti (left) sets up a shot with the crew during the shooting of Vikings, a coproduction involving Toronto’s Take 5 and Ireland’s Octagon Films. For more on how Canadian indie producers are making copros work with international partners, see page 23. 9 Up front 23 Playback Indie List 43 Muse at 15 Format trends, Mike Holmes’ brand Our annual survey of independent The Montreal-based, family-run at 10, industry execs turn a page to fi lm and TV production prodco on its growth and new ventures, prop printing, strategic partnerships guerrilla distribution 32 Education evolution How academic institutions and 50 The Back Page 16 Digital disruption training programs are adapting Web series writers Mark De Angelis, Canucks catch the wave to equip the industry’s next generation Naomi Snieckus and Amy Matysio’s no-fail tips for online glory. 18 Changing the stakes 40 Unions and Guilds How crowdfunding for equity stakes The industry’s professional bodies could open doors for new fi lm and are evolving to keep up with the TV fi nanciers demands on their members ® A PUBLICATION OF BRUNICO COMMUNICATIONS LTD. -

Ethan Banville Writing Experience

ETHAN BANVILLE [email protected] Canada 647-861-3554 U.S. 818-934-1780 Representation: Canada - Jennifer Hollyer, Ilana Miller - 416-928-1425 U.S. - Paul Weitzman, Preferred Artists - 818-990-0305 _______________________________________________________________________ WRITING EXPERIENCE 1/2013 - present “Virtually Perfect” - Marble Media CREATOR/WRITER Optioned single camera adult comedy pitch. Currently developing pitch to take to Canadian networks. 1/2013 - present “Chuck’s Choice” - DHX/YTV DEVELOPMENT WRITER Hired to write development script for 11 minute children’s animated series in contention with YTV. 12/2012 - present “Nerds and Monsters” - SlappHappy Cartoons/9 Story/YTV FREELANCE WRITER Hired to write freelance episodes of the new 11 minute animated cartoon “Nerds and Monsters.” 11/2012 - 11/2012 “Full Throttle” - Portfolio Entertainment PITCH CONSULTANT/STORY EDITOR Hired to help creator of multi-cam tween comedy develop, rewrite, and punch up his pitch to take out to networks. 7/2012-1/2012 “That App Kid” - Aircraft Pictures/Dolphin Entertainment CREATOR/EXECUTIVE PRODUCER Development deal: Sold pitch for episodic single camera tween comedy to Family Channel. 1 9/2012-11/2012 “Alps 11” DHX Entertainment DEVELOPMENT WRITER Hired to redevelop show, write new bible and promo script, with option to write pilot script. 7/2012-11/2012 “The Pods” - DHX Entertainment FREELANCE WRITER/CO-EXECUTIVE PRODUCER Hired to rewrite development episode for project in contention to go to series with YTV. 6/2012-11/2012 “Life Skillz” - 5x5 Media FREELANCE WRITER on coming of age feature film to be directed by Mark Steilen. 5/2012 - 11/2012 “Johnny Test” (Animated) - TELETOON/CARTOON NETWORK FREELANCE WRITER on seven episodes of Season 6 2/12 - 9/12 “Stand Up Kid” - WESTWIND PICTURES DEVELOPMENT WRITER Hired to develop series, write pitch pages and deliver sample script based on existing property. -

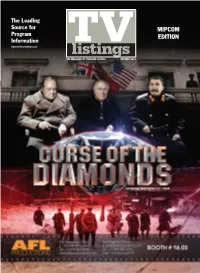

Mipcom Edition

*LIST_1013_COVER_LIS_410_COVER 9/19/13 6:13 PM Page 2 The Leading Source for MIPCOM Program EDITION Information www.worldscreenings.com THE MAGAZINE OF PROGRAM LISTINGS OCTOBER 2013 MIP_APP_2013_Layout 1 9/19/13 7:35 PM Page 1 World Screen App For iPhone and iPad DOWNLOAD IT NOW Program Listings | Stand Numbers | Event Schedule | Daily News Photo Blog | Hotel and Restaurant Directories | and more... Sponsored by Brought to you by *LIST_1013_LIS_1006_LISTINGS 9/19/13 6:03 PM Page 598 TV LISTINGS 3 In This Issue 4K MEDIA 53 West 23rd St., 11/Fl. 3 22 New York, NY 10010, U.S.A. 4K Media HBO 9 Story Entertainment Hoho Rights Tel: (1-212) 590-2100 Imagina International Sales 4 IMPS e-mail: [email protected], [email protected] 41 Entertainment Incendo A+E Networks website: www.yugioh.com ABC Commercial 23 ABS-CBN Corporation ITV-Inter Medya ITV Studios Global Entertainment 6 Kanal D activeTV Keshet International AFL Productions Ledafilms Alfred Haber Distribution all3media international 24 Stand: 13.11 American Cinema International Lionsgate Entertainment Contact: Shinichi Hanamoto, chmn. & pres. Mance Media 9 Story’s Peg + Cat 7 MarVista Entertainment corp. officer; Kristen Gray, SVP, business affairs; American Greetings Properties MediaBiz Animasia Studio Jennifer Coleman, VP, lic. & mktg.; Kaz Haruna; Peg + Cat (2-5 animated, 80x11 min.) Fol- APT Worldwide 25 Brian Lacey, intl. broadcast dist. cnslt. lows an adorable spirited little girl, Peg, and Armoza Formats MediaCorp Mediatoon Distribution her sidekick, Cat, as they embark on adven- 8 Miramax tures while learning basic math concepts Artear Mission Pictures International Artist View Entertainment Mondo TV S.p.A. -

Sounds High-Tech for New Jersey-Based NRG Energy, the Company Building and Running the Facility

The SCENES BY ERIC DOWDLE Folk artist’s Nauvoo Herald series to be unveiled at downtown Logan’s Gallery Walk Journal — Cache Vol. 99 No. 163 Friday, June 12, 2009 Bridgerland’s Daily Newspaper Logan, Utah $0.50 Weather WHO declares H1N1 pandemic High: 65 Low: 46 Chance Decision is first of Six confirmed swine flu of rain cases in Cache County its kind in 41 years - Page A10 By Charles Geraci GENEVA (AP) — Swine flu is staff writer now formally a pandemic, a decla- Update ration by U.N. health officials that will speed vaccine production and There are now six state laboratory-con- spur government spending to com- firmed cases of swine flu in Cache County, Energy bat the first global flu epidemic in according to the Bear River Health Depart- 41 years. ment. Thursday’s announcement by the The Herald Journal obtained the infor- Largest solar World Health Organization doesn’t mation Thursday — the same day the mean the virus is any more lethal World Health Organization declared a plant in U.S. to — only that its spread is considered global pandemic and the Utah Department unstoppable. of Health announced it was adjusting its be built in N.M. Since it was first detected in late testing guidelines for the virus. April in Mexico and the United Five of the six confirmed cases in the ALBUQUERQUE, N.M. States, swine flu has reached 74 county correspond to males — two pediat- (AP) — Utility officials countries, infecting nearly 29,000 ric cases under the age of 12, two between announced plans Thursday to people.