Report of Archeological Investigations for 2018

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Residential Financ Ng N

Residential Financ ng n the Colonias Report To the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development By: Perspectiva ICF Consulting Bruce Ferguson January 30, 2004 I TABLE OF CONTENTS I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY IV II. INTRODUCTION,. 1 III. METHODOLOGY J 1. LTTERATURE REVTEW ...................... 3 2. DATA ANALYSIS 3 3. INTERVIEWS AND FOCUS GROUPS 4 IV. BACKGROUND ON COLONIAS 5 1. INTRODUCTION tr a. Definitional lssues: What is a Colonia? ..........5 b. Continuing Growth .......,..6 c. lnternational Context. ...,,,,..,7 2. COLONIAS:A CLOSER LOOK. ..........8 a. Texas Colonias ........'l 0 b. Arizona Colonias .,.,.,.,14 c. New [Vexico Colonias ...,...,17 d. California Colonias .,...,.,21 3. CONCLUS|ONS........ ........24 V. RESIDENTIAL FINANCE IN COLONIAS 25 1. OVERVIEW OF KEY EXISTING RESIDENTIAL FINANCE ISSUES 25 2. CHARACTERISTICS OF HOUSING FINANCE IN COLONIAS......... 26 a. Factors affecting access to conventional housing finance 28 b. Key points from focus groups and interviews.............. 30 3. CURRENT ESTIMATED LENDING ACTIVITY IN COLONIAS......... 33 a. Texas Colonias 33 b. Arizona Colonias 36 c. New Mexico Colonias 3B d. California Colonias 40 4. CONCLUSIONS.,...... 42 VI. INTERNATIONAL PERSPECTIVES 44 1. OVERVIEW OF COLONIAS INTERNATIONALLY 44 a. Colonia Formation b. Colonias solve the individual's housing problem but at great public and private cost. ....46 c. Upgrading and/or slowing colonia formation requires a wide range of housing "solutions." ,.,,.,.,.,47 d. Financin9................ ...........48 2. COMPARAISON OF COLONIAS IN MEXICO AND IN THE U.S. .....................53 a. Colonia Formation .............53 b. Location ..........53 c. Size and Density ................54 d. Jurisdiction............... ..........54 e. Development Standards............... ........54 f. Community Organization............. ..........55 g. OverallView of Colonias ......................55 3. -

4-Year Work Plan by District for Fys 2015-2018

4 Year Work Plan by District for FYs 2015 - 2018 Overview Section §201.998 of the Transportation code requires that a Department Work Program report be provided to the Legislature. Under this law, the Texas Department of Transportation (TxDOT) provides the following information within this report. Consistently-formatted work program for each of TxDOT's 25 districts based on Unified Transportation Program. Covers four-year period and contains all projects that the district proposes to implement during that period. Includes progress report on major transportation projects and other district projects. Per 43 Texas Administrative Code Chapter 16 Subchapter C rule §16.106, a major transportation project is the planning, engineering, right of way acquisition, expansion, improvement, addition, or contract maintenance, other than the routine or contracted routine maintenance, of a bridge, highway, toll road, or toll road system on the state highway system that fulfills or satisfies a particular need, concern, or strategy of the department in meeting the transportation goals established under §16.105 of this subchapter (relating to Unified Transportation Program (UTP)). A project may be designated by the department as a major transportation project if it meets one or more of the criteria specified below: 1) The project has a total estimated cost of $500 million or more. All costs associated with the project from the environmental phase through final construction, including adequate contingencies and reserves for all cost elements, will be included in computing the total estimated cost regardless of the source of funding. The costs will be expressed in year of expenditure dollars. 2) There is a high level of public or legislative interest in the project. -

Archeological Survey Investigations at Martin Creek Lake State Park, Rusk County, Texas

Volume 2011 Article 11 2011 Archeological Survey Investigations at Martin Creek Lake State Park, Rusk County, Texas Timothy K. Perttula Heritage Research Center, Stephen F. Austin State University, [email protected] Bo Nelson Heritage Research Center, Stephen F. Austin State University, [email protected] Jon C. Lohse [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ita Part of the American Material Culture Commons, Archaeological Anthropology Commons, Environmental Studies Commons, Other American Studies Commons, Other Arts and Humanities Commons, Other History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons, and the United States History Commons Tell us how this article helped you. Cite this Record Perttula, Timothy K.; Nelson, Bo; and Lohse, Jon C. (2011) "Archeological Survey Investigations at Martin Creek Lake State Park, Rusk County, Texas," Index of Texas Archaeology: Open Access Gray Literature from the Lone Star State: Vol. 2011, Article 11. https://doi.org/10.21112/ita.2011.1.11 ISSN: 2475-9333 Available at: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ita/vol2011/iss1/11 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Center for Regional Heritage Research at SFA ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Index of Texas Archaeology: Open Access Gray Literature from the Lone Star State by an authorized editor of SFA ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Archeological Survey Investigations at Martin Creek Lake State Park, Rusk County, Texas Creative Commons License This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 4.0 License This article is available in Index of Texas Archaeology: Open Access Gray Literature from the Lone Star State: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ita/vol2011/iss1/11 Archeological Survey Investigations at Martin Creek Lake State Park, Rusk County, Texas by Timothy K. -

LONE STAR STATE Stargazing

LONE STAR STATE Stargazing IndependenceTitle.com Keep Your Eyes to the Sky! These are some of the best places to stargaze in Texas Big Bend National Park Big Bend National Park is not only Texas’s most famous park— it is also known as one of the most outstanding places in North America for star gazing. Thanks to the sparse human occupation of this region, it has the least light pollution of any other National Park unit in the lower 48 states. This can be a real surprise to visitors when they are outside in Big Bend at night and see the Milky Way in its full glory for perhaps the first time in their life. Needless to say, you can stargaze just about anywhere in Big Bend, but there are a few spots you might want to consider. If you’re an admirer of astronomy, bring your telescope to the Marathon Sky Park. You can also see the stars from the stargazing platform atop Eve’s Garden Bed and Breakfast in Marathon. Brazos Bend State Park Located an hour outside of Houston, Brazos Bend State Park is a great place for any astronomical enthusiast. Not only is it far removed from the light pollution of the Lone Star State’s biggest city, it’s home to the George Observatory, where visitors can view planetary objects up close and personal. LONE STAR STATE Caprock Canyons State Park Home to the only wild bison herd in the state of Texas, Caprock Canyon State Park in the Texas panhandle has stunning views of constellations. -

SUBCOMMITTEE on ARTICLES VI, VII, & VIII AGENDA MONDAY, MAY 2, 2016 10:00 A.M. ROOM E1.030 I. II. Charge #17: Review Histori

TEXAS HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES COMMITTEE ON APPROPRIATIONS SUBCOMMITTEE ON ARTICLES VI, VII, & VIII LARRY GONZALES, CHAIR AGENDA MONDAY, MAY 2, 2016 10:00 A.M. ROOM E1.030 I. CALL TO ORDER II. CHAIRMAN’S OPENING REMARKS III. INVITED TESTIMONY Charge #17: Review historic funding levels and methods of financing for the state parks system. Study recent legislative enactments including the General Appropriations Act(84R), HB 158 (84R), and SB 1366 (84R) to determine the effect of the significant increase in funding, specifically capital program funding, on parks across the state. LEGISLATIVE BUDGET BOARD • Michael Wales, Analyst • Mark Wiles, Manager, Natural Resources & Judiciary Team TEXAS PARKS AND WILDLIFE DEPARTMENT • Carter Smith, Executive Director • Brent Leisure, State Park Division Director • Jessica Davisson, Infrastructure Division Director IV. PUBLIC TESTIMONY V. FINAL COMMENTS VI. ADJOURNMENT Overview of State Park System Funding PRESENTED TO HOUSE APPROPRIATIONS SUBCOMMITTEE ON ARTICLES VI, VIII, AND VIII LEGISLATIVE BUDGET BOARD STAFF MAY 2016 Overview of State Park System Funding The Parks and Wildlife Department (TPWD) state parks system consists of 95 State Historic Sites, State Natural Areas, and State Parks, of which 91 are open to the public. State park-related appropriations fund operating the sites, the maintenance and capital improvements of state park infrastructure, associated administrative functions, providing grants to local parks and other entities for recreation opportunities, and advertising and publications related to the parks system. ● Total state parks-related appropriations for the 2016-17 biennium totals $375.9 million in All Funds, an increase of $83.6 million, or 28.6 percent , above the 2014-15 actual funding level. -

Parks, Recreation and Open Space M Aster Plan

December 2009 Schrickel, Rollins and Associates, Inc. Parks, Recreation and Open Space Master Plan Page 1 Table of Contents Acknowledgements Chapter 1 - Introduction Chapter 2 - Community Profi le and Park & Recreation Resources Chapter 3 - The Planning Process and Standards Chapter 4 - Needs Assessments Chapter 5 - Environmental Preservation and Open Space Plan Chapter 6 - Priorities, Reccommendations and Implementation Bibliography Appendix Page 2 Acknowledgements City Council Ted Reynolds, Mayor Dr. Robert Kelly, District 1 Gayle White, District 2 Dale Sturgeon, District 3 John Warren, Mayor Pro Tem, District 4 Parks and Recreation Board Ben Oefi nger, Chairman Casey Dugger Jeff LeClair Burt Powell Barbara Robinson Randy Stone Mary Ann Wheatley City Staff Chester R. Nolen, City Manager Rick Holden, Assistant City Manager Max Robertson, Director Parks & Recreation Division Mike Utecht, Superintendent of Parks and Recreation Kristi Dempsey, Parks & Recreation Gina Moore, Recreation Manager Donna Jackson Zimmerman, Director of Development Services Ann Powell, City Planner Project Team Schrickel, Rollins and Associates, Inc. Linda Jordan, Project Manager Suzanne C. Sweek, RLA, ASLA, Project Coordinator Cathy Acuna, Planner Michael Kashuba, Planner Raymond Turco and Associates Raymond Turco Page 3 Page 4 Chapter 1 Introduction This plan has been prepared in compliance Standards developed for Cleburne and discussed with the guidelines for park and recreation in Chapter 3. “Our mission is to enhance the quality of life system master plans established by Texas Parks in Cleburne through people, places, programs & Wildlife (TP&W). TP&W provides a variety Preservation of the City’s natural environment is and partnerships.” - Cleburne Parks and of matching grant programs, and master plans discussed in Chapter 5. -

Draft Environmental Assessment for North Texas Optimization of Airspace and Procedures in the Metroplex

Draft Environmental Assessment for North Texas Optimization of Airspace and Procedures in the Metroplex Volume II - Appendices September 2013 Prepared by: United States Department of Transportation Federal Aviation Administration Fort Worth, Texas Table of Contents APPENDIX A A.1 First Early Notification Announcement................................................................................ 1 A.1.1 Early Notification Letters ..................................................................................................... 1 A.1.2 Comments Received From the First Announcement........................................................23 A.1.3 Outreach Meetings............................................................................................................49 APPENDIX B B.1 List of Preparers.................................................................................................................. 1 B.1 Receiving Parties & Draft EA Notification of Availability..................................................... 3 APPENDIX C C.1 Contact Information............................................................................................................. 1 C.2 References.......................................................................................................................... 1 APPENDIX D D.1 List of Acronyms.................................................................................................................. 1 D.2 Glossary ............................................................................................................................. -

Bibliography-Of-Texas-Speleology

1. Anonymous. n.d. University of Texas Bulletin No. 4631, pp. 51. 2. Anonymous. 1992. Article on Pendejo Cave. Washington Post, 10 February 1992. 3. Anonymous. 1992. Article on bats. Science News, 8 February 1992. 4. Anonymous. 2000. National Geographic, 2000 (December). 5. Anonymous. n.d. Believe odd Texas caves is Confederate mine; big rock door may be clue to mystery. 6. Anonymous. n.d. The big dig. Fault Zone, 4:8. 7. Anonymous. n.d. Cannibals roam Texas cave. Georgetown (?). 8. Anonymous. n.d. Cavern under highway is plugged by road crew. Source unknown. 9. Anonymous. n.d. Caverns of Sonora: Better Interiors. Olde Mill Publ. Co., West Texas Educators Credit Union. 10. Anonymous. n.d. Crawling, swimming spelunkers discover new rooms of cave. Austin(?). Source unknown. 11. Anonymous. n.d. Discovery (of a sort) in Airmen's Cave. Fault Zone, 5:16. 12. Anonymous. n.d. Footnotes. Fault Zone, 5:13. 13. Anonymous. n.d. Help the blind... that is, the Texas blind salamander [Brochure]: Texas Nature Conservancy. 2 pp. 14. Anonymous. n.d. Honey Creek map. Fault Zone, 4:2. 15. Anonymous. n.d. The Langtry mini-project. Fault Zone, 5:3-5. 16. Anonymous. n.d. Neuville or Gunnels Cave. http:// www.shelbycountytexashistory.org/neuvillecave.htm [accessed 9 May 2008]. 17. Anonymous. n.d. Palo Duro Canyon State Scenic Park. Austin: Texas Parks and Wildlife Department. 2 pp. 18. Anonymous. n.d. Texas blind salamander (Typhlomolge rathbuni). Mississippi Underground Dispatch, 3(9):8. 19. Anonymous. n.d. The TSA at Cascade Caverns. Fault Zone, 4:1-3, 7-8. -

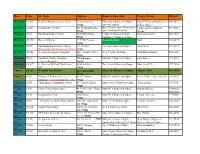

Community Service Worksheet

Place Code Site Name Address Hours of Operation Contact Person Phone # Westside CS116 Franklin Mountains State Park Transmountain Mon-Sun 8:00am to 5:00pm Robert Pichardo/Raul Gomez 566-6441 79912 MALES ONLY & Erika Rubio Westside CS127 Galatzan Rec Center 650 Wallenberg Dr. Mon - Th 1pm to 9pm; Friday 1pm to Carlos Apodaca Robert 581-5182 79912 6pm; Saturday 9am to 2pm Owens Westside CS27 Don Haskins Rec Center 7400 High Ridge Fridays 2:00pm to 6:00pm Rick Armendariz 587-1623 79912 Saturdays 9:00am to 2:00pm Westside CS140 Rescue Mission 1949 W. Paisano Residents Only Staff 532-2575 79922 Westside CS101 Environmental Services (West) 121 Atlantic Tue-Sat 8:00am to 4:00pm Jose Flores 873-8633 Martin Sandiego/Main Supervisor 472-4844 79922 Westside CS142 Westside Regional Command 4801 Osborne Drive Wed 7:00am-10:00am Orlando Hernandez 585-6088 79922 Canutillo CS111 Canutillo County Nutrition 7361 Bosque Mon-Fri 9:00am to 1:00pm Irma Torres 877-2622 (close to Westside) 79835 Canutillo CS117 St. Vincent De Paul Thrift Store 6950 3rd Street Tues-Sat 10:00am to 6:00pm Mari Cruz P. Lee 877-7030 (W) 79835 Vinton CS143 Westside Field Office 435 Vinton Rd Mon-Fri 8:00am to 6:00pm. Support Staff 886-1040 79821 Vinton CS67 Village of Vinton-(close to 436 E. Vinton Mon-Fri 8:00am to 4:00pm Perch Valdez, José Alarcón 383-6993 Anthony) avail for light duty- No 79821 Central- CS53 Chihuahuita Community Center 417 Charles Road Mon - Fri 11:00am to 6:00pm Patricia Rios 533-6909 DT 79901 Central- CS11 Civic Center Maintenance #1 Civic Center Plaza Mon-Fri 6:00am to 4:00pm Manny Molina 534-0626/ DT 79901 534-0644 Central- CS14 Opportunity Center 1208 Myrtle Mon-Fri 6:00am to 6:00p.m. -

Consumer Plannlng Section Comprehensive Plannlng Branch

Consumer Plannlng Section Comprehensive Plannlng Branch, Parks Division Texas Parks and Wildlife Department Austin, Texas Texans Outdoors: An Analysis of 1985 Participation in Outdoor Recreation Activities By Kathryn N. Nichols and Andrew P. Goldbloom Under the Direction of James A. Deloney November, 1989 Comprehensive Planning Branch, Parks Division Texas Parks and Wildlife Department 4200 Smith School Road, Austin, Texas 78744 (512) 389-4900 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Conducting a mail survey requires accuracy and timeliness in every single task. Each individualized survey had to be accounted for, both going out and coming back. Each mailing had to meet a strict deadline. The authors are indebted to all the people who worked on this project. The staff of the Comprehensive Planning Branch, Parks Division, deserve special thanks. This dedicated crew signed letters, mailed, remailed, coded, and entered the data of a twenty-page questionnaire that was sent to over twenty-five thousand Texans with over twelve thousand returned completed. Many other Parks Division staff outside the branch volunteered to assist with stuffing and labeling thousands of envelopes as deadlines drew near. We thank the staff of the Information Services Section for their cooperation in providing individualized letters and labels for survey mailings. We also appreciate the dedication of the staff in the mailroom for processing up wards of seventy-five thousand pieces of mail. Lastly, we thank the staff in the print shop for their courteous assistance in reproducing the various documents. Although the above are gratefully acknowledged, they are absolved from any responsibility for any errors or omissions that may have occurred. ii TEXANS OUTDOORS: AN ANALYSIS OF 1985 PARTICIPATION IN OUTDOOR RECREATION ACTIVITIES TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ........................................................................................................... -

Artecodevreport TCT 2010.Pdf

Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 1 Selecting Case Study Communities & Study Approach .............................................................. 4 Texas Case Studies ...................................................................................................................... 7 City of Amarillo, Texas & Panhandle Region .......................................................................... 7 Key Findings & Lessons Learned from Amarillo & Texas Panhandle .................................. 7 Globe-News Center and Downtown Redevelopment ........................................................ 8 Window on a Wider World (WOWW) .............................................................................. 11 TEXAS the Musical Drama at the Pioneer Amphitheatre ................................................. 13 Summary .......................................................................................................................... 14 City of Clifton, Texas ............................................................................................................. 15 Key Findings & Lessons Learned from Clifton .................................................................. 15 Artists’ Colony .................................................................................................................. 16 Bosque Arts Center .......................................................................................................... -

The Chiricahua Apache from 1886-1914, 35 Am

American Indian Law Review Volume 35 | Number 1 1-1-2010 Values in Transition: The hirC icahua Apache from 1886-1914 John W. Ragsdale Jr. Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.ou.edu/ailr Part of the Indian and Aboriginal Law Commons, Indigenous Studies Commons, Other History Commons, Other Languages, Societies, and Cultures Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation John W. Ragsdale Jr., Values in Transition: The Chiricahua Apache from 1886-1914, 35 Am. Indian L. Rev. (2010), https://digitalcommons.law.ou.edu/ailr/vol35/iss1/9 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by University of Oklahoma College of Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in American Indian Law Review by an authorized editor of University of Oklahoma College of Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. VALUES IN TRANSITION: THE CHIRICAHUA APACHE FROM 1886-1914 John W Ragsdale, Jr.* Abstract Law confirms but seldom determines the course of a society. Values and beliefs, instead, are the true polestars, incrementally implemented by the laws, customs, and policies. The Chiricahua Apache, a tribal society of hunters, gatherers, and raiders in the mountains and deserts of the Southwest, were squeezed between the growing populations and economies of the United States and Mexico. Raiding brought response, reprisal, and ultimately confinement at the loathsome San Carlos Reservation. Though most Chiricahua submitted to the beginnings of assimilation, a number of the hardiest and least malleable did not. Periodic breakouts, wild raids through New Mexico and Arizona, and a labyrinthian, nearly impenetrable sanctuary in the Sierra Madre led the United States to an extraordinary and unprincipled overreaction.