Great Ocean Gulf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Taylors Hill-Werribee South Sunbury-Gisborne Hurstbridge-Lilydale Wandin East-Cockatoo Pakenham-Mornington South West

TAYLORS HILL-WERRIBEE SOUTH SUNBURY-GISBORNE HURSTBRIDGE-LILYDALE WANDIN EAST-COCKATOO PAKENHAM-MORNINGTON SOUTH WEST Metro/Country Postcode Suburb Metro 3200 Frankston North Metro 3201 Carrum Downs Metro 3202 Heatherton Metro 3204 Bentleigh, McKinnon, Ormond Metro 3205 South Melbourne Metro 3206 Albert Park, Middle Park Metro 3207 Port Melbourne Country 3211 LiQle River Country 3212 Avalon, Lara, Point Wilson Country 3214 Corio, Norlane, North Shore Country 3215 Bell Park, Bell Post Hill, Drumcondra, Hamlyn Heights, North Geelong, Rippleside Country 3216 Belmont, Freshwater Creek, Grovedale, Highton, Marhsall, Mt Dunede, Wandana Heights, Waurn Ponds Country 3217 Deakin University - Geelong Country 3218 Geelong West, Herne Hill, Manifold Heights Country 3219 Breakwater, East Geelong, Newcomb, St Albans Park, Thomson, Whington Country 3220 Geelong, Newtown, South Geelong Anakie, Barrabool, Batesford, Bellarine, Ceres, Fyansford, Geelong MC, Gnarwarry, Grey River, KenneQ River, Lovely Banks, Moolap, Moorabool, Murgheboluc, Seperaon Creek, Country 3221 Staughtonvale, Stone Haven, Sugarloaf, Wallington, Wongarra, Wye River Country 3222 Clilon Springs, Curlewis, Drysdale, Mannerim, Marcus Hill Country 3223 Indented Head, Port Arlington, St Leonards Country 3224 Leopold Country 3225 Point Lonsdale, Queenscliffe, Swan Bay, Swan Island Country 3226 Ocean Grove Country 3227 Barwon Heads, Breamlea, Connewarre Country 3228 Bellbrae, Bells Beach, jan Juc, Torquay Country 3230 Anglesea Country 3231 Airleys Inlet, Big Hill, Eastern View, Fairhaven, Moggs -

Colac Otway Planning Scheme

COLAC OTWAY PLANNING SCHEME 21.07 REFERENCE DOCUMENTS 26/10/2017 C86 The following strategic studies have informed the preparation of this planning scheme. All relevant material has been included in the Scheme and decisions makers should use these documents for background research only. Material in these documents that potentially provides guidance on decision making but is not specifically referenced by the Scheme should not be given any weight. Settlement Apollo Bay Structure Plan (2007) Apollo Bay Settlement Boundary & Urban Design Review (2012) Colac Structure Plan (2007) Apollo Bay and Marengo Neighbourhood Character Review Background Report (2003) Barwon Downs Township Masterplan (2006) Beeac Township Masterplan (2001) Beech Forest Township Masterplan (2003) Birregurra and Forrest Community Infrastructure Plans (2012) Birregurra Neighbourhood Character Study (2012) Birregurra Structure Plan (2013) Carlisle River Township Masterplan (2004) Colac Otway Rural Living Strategy (2011) Cressy Township Masterplan (2007) Forrest Structure Plan (2011) Forrest Township Masterplan (2007) Gellibrand Township Masterplan (2004) Kennett River, Wye River and Separation Creek Structure Plans (2008) Lavers Hill Township Masterplan (2006) Siting and Design Guidelines for Structures on the Victorian Coast, Victorian Coastal Council (1997) Skenes Creek, Kennett River, Wye River and Separation Creek Neighbourhood Character Study (2005) Swan Marsh Township Masterplan (2001) Colac Commercial Centre Parking Precinct Plan, AECOM (2011) Colac Otway Public -

P a Rk N O Te S

Great Otway National Park and Otway Forest Park Torquay to Kennett River Angahook Visitor Guide “Rugged coastlines, dramatic cliff faces, sandy beaches and rock platforms, steep forested ridges and deep valleys of tall forest and fern clad gullies embracing spectacular waterfalls all feature here. Angahook comes from the language of the Wauthaurung people, whose ancestors lived for thousands of years off the lands in the eastern areas of the Otway Ranges. Wauthaurung people continue their spiritual and physical connection here today.” -Ranger In Charge, Dale Antonysen A daily bus service between Geelong, Lorne and Wedge-tailed Apollo Bay connects with train services to Eagle. Melbourne. For timetable details call V/Line Country Information on 13 2232. The Parks provide n o t evital s homes, food and shelter for Picnicking and Camping Eagles and a Picnic opportunities abound with lovely settings huge variety of at Blanket Leaf, Sheoak, Distillery Creek, Grey other species, including 43 River and Moggs Creek, to name a few. There species only found are many beautiful places to picnic, be sure to in the Parks and plan your visit to get the most out of your day! nowhere else in There are excellent camping opportunities the world! throughout the Parks. Whether you are looking Getting out and about for a family friendly place to park your caravan or a solitary night under the stars there’s something The Parks provide a multitude of activities for to cater to every need. Please refer to the Park visitors to enjoy. Camping, fishing, horse riding, Camping Guide overleaf for further information. -

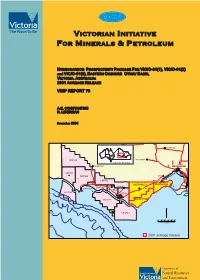

V I F M & P V I F M & P

VMPi VIICTORIAN NITIATIVE FMOR INERALS &P ETROLEUM HYDROCARBON P ROSPECTIVITY P ACKAGE F OR VIC/O-01(1), VIC/O-01(2) andVIC/O-01(3) , E ASTERN O NSHORE O TWAY B ASIN, VAICTORIA, USTRALIA: 2001 ACREAGE R ELEASE VIMP REPORT 70 A.E. CONSTANTINE N. LIBERMAN November 2001 KYNETON PEP160 BALLARAT AREA OF INTEREST HAMILTON MELBOURNE PEP151 PEP150 LARA PEP159 GEELONG VIC/O-01(1) VIC/O-01(3) PEP152 (b) COBDEN 200m COLAC PORTLAND PEP154(a) VIC/P46 1000m PEP153 VIC/O-01(2) VIC/P44 2000m 3000m VIC/P43 0 10 20 30 40 50 Km 4000m 2001 acreage release . VIMP Report 70 Hydrocarbon prospectivity package for VIC/O-01(1), VIC/O-01(2) and VIC/O-01(3), Eastern Onshore Otway Basin, Victoria, Australia 2001 Acreage Release A. Constantine and N. Liberman November 2001 Bibliographic reference: CONSTANTINE, A. and LIBERMAN, N., 2001. Hydrocarbon Prospectivity Package for VIC/O-01(1), VIC/O-01(2) and VIC/O-01(3), Eastern Onshore Otway Basin, Victoria, Australia. 2001 Acreage Release. Victorian Initiative for Minerals and Petroleum Report 70. Department of Natural Resources and Environment. © Crown (State of Victoria) Copyright 2001 Petroleum Development ISSN 1323 4536 ISBN 0 7306 9472 0 (Hard Copy) ISBN 0 7306 9473 9 (CD-ROM) This report may be purchased from: Business Centre Minerals & Petroleum Department of Natural Resources and Environment 8th Floor, 240 Victoria Parade East Melbourne, Victoria 3002, Australia For further technical information contact: Manager Petroleum Development Department of Natural Resources and Environment PO Box 500 East Melbourne, Victoria 3002, Australia Website: www.nre.vic.gov.au/minpet/index.htm Authorship and Acknowledgments: The package was compiled and collated by the Basin Studies Group of the Petroleum Development Unit. -

A Brief Audit of the Corangamite Groundwater Monitoring Program

A BRIEF AUDIT OF THE CORANGAMITE GROUNDWATER MONITORING PROGRAM November 2001 AGRICULTURE VICTORIA - BENDIGO CENTRE FOR LAND PROTECTION RESEARCH Monitoring Report No. 42 Ó The State of Victoria, Department of Natural Resources & Environment, 2001 Published by the Department of Natural Resources and Environment Agriculture Victoria - Bendigo – Centre for Land Protection Research Cnr Midland Highway and Taylor St Epsom Vic 3551 Australia Ó The State of Victoria, Department of Natural Resources & Environment, 2001 Published by the Department of Natural Resources and Environment Agriculture Victoria - Bendigo – Centre for Land Protection Research Cnr Midland Highway and Taylor St Epsom Vic 3551 Australia Website: http://www.nre.vic.gov.au/clpr The National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry: Pillai, Mayavan A brief audit of the Corangamite groundwater monitoring program ISBN 0 7311 4989 0 1. Groundwater – Victoria – Corangamite, Lake, Region. 2. Hydrogeological surveys – Victoria – Corangamite, Lake, Region. I. Centre for Land Protection Research (Vic.). II. Title. (Series : Monitoring report (Centre for Land Protection Research) ; 42). 551.49099457 ISSN 1324 4388 This publication may be of assistance to you but the State of Victoria and its employees do not guarantee that the publication is without flaw of any kind or is wholly appropriate for your particular purposes and therefore disclaims all liability for any error, loss or other consequence which may arise from you relying on any information in this publication. Agriculture Victoria Bendigo - CLPR SUMMARY Across the Corangamite Salinity Region there are in the order of 580 NRE and community groundwater monitoring bores, grouped in 28 distinct monitoring networks that have progressively been established since the late 1980s. -

Barwon Water Annual Report 2010-2011

2010-2011 ANNUAL REPORT SERVICE AREA MAP | PARt 1 – Year in review | PARt 2 – WATER CONSUMPTION AND DROUGHT RESPonse | PARt 3 – ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL SUSTAINABILITY SERVICE AREA 2 P ARt 4 – CORPORATE INFORMAtion | PARt 5 – PERFORMANCE REPORt | PARt 6 – Financial stATEments | PARt 7 – disclOSURE INDEX CONTENTS Service area map 2 Part 1 – Year in review 4 About us 4 At a glance 6 Message from the Chairman 7 Message from the Managing Director 8 Summary of financial results 10 P art 2 – Water consumption and drought response 14 Water consumption report 14 Corporate water consumption 15 Major non-residential water users 15 Drought Response Plan 16 Part 3 – Environmental and social sustainability 17 Environmental sustainability – Environmental Consultative Committee report 17 – Water Supply Demand Strategy (2012-2017) 17 – Recycled water 17 – Conservation programs and initiatives 18 – Catchment management and biodiversity 19 – Greenhouse gas emissions 20 – Bulk entitlement reporting 23 Social sustainability – Customer Consultative Committee report 27 – Community Service Obligations 28 Part 4 – Corporate information 29 Organisational structure 29 Board committees 30 Board Directors 31 Employment data 33 Health, safety and environment 34 Access to information 36 Other Acts 37 Applicable policies 38 Part 5 – Performance report 39 Part 6 – Financial statements 44 Part 7 – Disclosure index 81 B ARWON WATER ANNUAL REPORt 2010-2011 3 SERVICE AREA Map | PARt 1 – YeAR IN REVIEW | PARt 2 – WATER CONSUMPTION AND DROUGHT RESPonse | PARt 3 – ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL SUSTAINABILITY PART 1 YEAR IN REVIEW A bout us A ssets The Colac system provides water to urban and rural districts extending as far – 10 major reservoirs B arwon Water (Barwon Region Water north as Cressy. -

Groundwater Impact Assessment – Conceptual Report Onshore Otway Basin, Victoria

VICTORIAN GAS PROGRAM Groundwater impact assessment – Conceptual report Onshore Otway Basin, Victoria S. Torkzaban, M. Hocking, A. Gaal, S. Manamperi & C.P. Iverach Victorian Gas Program Technical Report 34 September 2020 Authorised by the Director, Geological Survey of Victoria Department of Jobs, Precincts and Regions 1 Spring Street Melbourne Victoria 3000 Telephone (03) 9651 9999 © Copyright State of Victoria, 2020. Department of Jobs, Precincts and Regions 2020 Except for any logos, emblems, trademarks, artwork and photography this work is made available under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia licence. To view a copy of this licence, visit creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/au. It is a condition of this Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Licence that you must give credit to the original author who is the State of Victoria. This document is also available in an accessible format at www.djpr.vic.gov.au Bibliographic reference TORKZABAN, S., HOCKING, M., GAAL, A., MANAMPERI, S. & IVERACH, C.P., 2020. Groundwater impact assessment - conceptual report, onshore Otway Basin, Victoria. Victorian Gas Program Technical Report 34. Geological Survey of Victoria. Department of Jobs, Precincts and Regions. Melbourne, Victoria. 94p. ISBN 978-1-76090-385-5 (pdf/online/MS word) Geological Survey of Victoria Catalogue Record 161884 Key Words conceptual model, gas, groundwater, Otway Basin, water balance Acknowledgements The CAT3D recharge model was provided by Craig Beverly (Agriculture Victoria). Bore hydrographs were developed by Tiffany Bold, and Cassady O’Neill and Josh Grover provided gas/groundwater volumetric production calculations and potentiometric surface maps. Karsten Michael, Praveen Rachakonda and Paul Wilkes (CSIRO) provided review comments and Randal Nott (DELWP) reviewed the report. -

Annual Report 2016-2017 Service Area

Annual Report 2016-2017 Service Area Water District Lakes Barwon Water reservoir Special water supply catchment Water channel/pipelines Main sewer Water service basin/tank Water treatment plant Groundwater production bores Water reclamation plants Sewer Flow Management Facility Recycled Water Plant Recycled water tank Recycled water pipeline Outfall 02 | Barwon Water Annual Report 2016-17 Contents Part 1 – Year in review 4 Part 4 – Corporate information 35 About us 5 Organisational structure 36 At a glance 7 Board committees 37 Message from the Chair and Managing Director 8 Board Directors 38 Summary of financial results 10 Employment data 40 Health, Safety and Wellbeing 43 Part 2 – Water consumption 13 Safety, Quality and Environment 44 Water consumption report 14 Access to information 45 Corporate water consumption 16 Other Acts 46 Major non-residential water users 16 Applicable policies 46 Part 3 – Environmental and social sustainability 17 Part 5 – Performance report 48 Environmental sustainability 18 Part 6 – Financial statements 57 • Sustainable water use 18 • Community engagement 21 Part 7 – Disclosure index 109 • Drought Response Plan 22 • Drinking water quality 22 • Environmental flows 22 • Other statutory obligations 23 Water District • Carbon emissions 25 Lakes • Bulk entitlement reporting 27 Barwon Water reservoir Social sustainability 33 Special water supply catchment • Customer Consultative Committee report 33 Water channel/pipelines Main sewer • Community Service Obligations 33 Water service basin/tank Water treatment plant Groundwater production bores Water reclamation plants Sewer Flow Management Facility Recycled Water Plant Recycled water tank Recycled water pipeline Outfall Part 1: Year in review 04 | Barwon Water Annual Report 2016-17 Part 1: Year in review Responsible Body Declaration We service a community of more than the economic, social and environmental 300,000 permanent residents over 8,100 dimensions of regional prosperity: In accordance with the Financial square kilometres. -

Barwon Downs Borefield

Barwon Downs Borefield Background and Submission 26 November 2018 1 Acknowledgements Traditional owner acknowledgement Barwon Water acknowledges the traditional custodians of the land on which we live today. We pay our respect to their Elders past, present and future. We recognise and respect their culture, beliefs and ongoing connection to the land over thousands of years. We would also like to give a special thanks to Kuuyang Maar, who have provided invaluable input and insight during the engagement process. Barwon Downs Groundwater Community Reference Group acknowledgement We would like to thank our Community Reference Group1 who have been actively involved in the Barwon Downs licence renewal project since 2013. Barwon Water greatly appreciates the dedication and insight each member contributed to this project. As well as ensuring that the monitoring program captured and addressed key areas of community concern, the reference group also provided valuable support to Barwon Water during the broader engagement process with the local community. Each community reference group member has dedicated a substantial amount of time and effort over the past five years for which we are very grateful. Through the process we have heard a diverse range of opinions, engaged in rich discussions and seen the project through the lens of the community. Members of the community reference group we would like to thank are: Jan Greig (Chair) Doug Chant Gavin Brien Robin Povey Malcolm Gardiner Hans Fankhanel Robert Maxwell Henry Bongers Community workshop participants’ acknowledgement We would like to thank all the participants who were involved in the 2017 Barwon Downs licence renewal community and stakeholder workshops for both their time, and their considered and thoughtful contributions. -

Barwon Downs Technical Works Program Barwon Water

Barwon Downs Technical Works Program Barwon Water Integration Report FINAL REPORT 22 March 2017 Integration Report Barwon Water Integration Report Barwon Downs Technical Works Program Project No: IS129200 Document Title: Integration Report Document No.: IS129200-100 Revision: FINAL REPORT Date: 22 March 2017 Client Name: Barwon Water Client No: Project Manager: Louise Lennon Author: Louise Lennon File Name: J:\IE\Projects\03_Southern\IS129200\21 Deliverables\Integration report\Final report\Barwon Downs Integration Report FINAL REPORT.docx Jacobs Group (Australia) Pty Limited ABN 37 001 024 095 Floor 11, 452 Flinders Street Melbourne VIC 3000 PO Box 312, Flinders Lane Melbourne VIC 8009 Australia T +61 3 8668 3000 F +61 3 8668 3001 www.jacobs.com © Copyright 2017 Jacobs Group (Australia) Pty Limited. The concepts and information contained in this document are the property of Jacobs. Use or copying of this document in whole or in part without the written permission of Jacobs constitutes an infringement of copyright. Limitation: This report has been prepared on behalf of, and for the exclusive use of Jacobs’ Client, and is subject to, and issued in accordance with, the provisions of the contract between Jacobs and the Client. Jacobs accepts no liability or responsibility whatsoever for, or in respect of, any use of, or reliance upon, this report by any third party. Document history and status Revision Date Description By Review Approved DRAFT Preliminary draft report NU ,FD, LL LL LL DRAFT v2 13/09/2016 Draft report LL GH GH FINAL 25/11/2016 Final draft report LL SP SP FINAL 22/03/2017 Final report LL GH GH IS129200-100 i Integration Report Contents An important note about your report .................................................................................................................. -

Strategic Fire Management Plan

Strategic fire management plan Otway District 2017 – 2020 Shires of Corangamite, Colac Otway and Surf Coast Inset a pic (from Wye fire?) Version Control Table Version Release Date Author Changes 1.0 4 November 2016 Cheryl Nagel and First complete working draft of plan for review of Peter Ashton Steering Group 1.1 9 November 2016 Cheryl Nagel and Draft refined throughout and provided to Project Peter Ashton Control Group for review 1.2 10 November 2016 Cheryl Nagel and Draft updated to include Project Control Group Peter Ashton direction and provided to members of all three MFMPCs for review and endorsement, specifically: Moved aim and objectives to front Reduced section on vulnerable people Created new section of strategic direction headlines from action table Minor text refinement 1.3 11 November 2016 Cheryl Nagel and Actions removed from document with strategic Peter Ashton directions headlines retained, under direction of project control group. Other minor updates. 1.4 15 November 2016 Cheryl Nagel and Minor adjustments following further direction of Peter Ashton the project control group. Submitted to each MFMPC and MEMPC for endorsement. 1.5 21 November 2016 Cheryl Nagel and Minor adjustments to incorporate MFMPC and Peter Ashton MEMPC review, minor editing and formatting improvements. Submitted to the Barwon South West Regional Fire Management Planning Committee for review 2 3 Front cover photograph – Fire approaching Wye River on Christmas day 2015; Andrew Hack Context statement This is the first version of a strategic fire management plan across the three Otway Shires. It replaces and supersedes the Municipal Fire Management Plans of Corangamite Shire, Colac Otway Shire and Surf Coast Shire which all have an expiry date of March 2017. -

Great Otway Destination Management Plan 2009

CARING FOR COUNTRY — THE OTWAYS AND YOU Great Otway National Park and Otway Forest Park Management Plan December 2009 Published in December 2009 by Parks Victoria, Level 10, 535 Bourke Street, Melbourne, Victoria 3000 and the Department of Sustainability and Environment, 8 Nicholson Street, East Melbourne 3002 Parks Victoria and DSE 2009, Caring for Country — The Otways and You. Great Otway National Park and Otway Forest Park Management Plan, Parks Victoria and DSE, Melbourne Cover photos from top left: Gunditjmara and Kirrae Whurrong dance group (Photo: Terry Woodcroft), and Melba Gully, Spot-tailed Quoll and Cora Lynn Cascades (Photos: Parks Victoria) National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Caring for Country — The Otways and You. Great Otway National Park and Otway Forest Park Management Plan / Parks Victoria and Dept of Sustainability and Environment ISBN 9780731183845 (pbk) Bibliography. National parks and reserves--Victoria--Otway Range. Tourism--Victoria--Otway Range--Planning. Recreation--Victoria--Otway Range--Planning. Otway National Park (Vic.) Otway Forest Park (Vic.) Parks Victoria. Victoria. Dept of Sustainability and Environment 333.783099457 Acknowledgements Acknowledgement of Country : In their rich culture, Aboriginal Australians are intrinsically connected to the continent — including the area now known as Victoria. Parks Victoria and the Department of Sustainability and Environment recognise that the parks are part of Country of the Traditional Owners. Parks Victoria and the Department of Sustainability and Environment are grateful to all those organisations and individuals who have contributed to this Management Plan. Note: Technical terms used in this plan are explained in the Glossary at the end of the plan. Disclaimers This plan is prepared without prejudice to any negotiated or litigated outcome of any native title determination applications covering land or waters in the plan’s area.