Whale Teeth Tabua, Chiefship and Power in Eastern Fiji

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Case for Lau and Namosi Masilina Tuiloa Rotuivaqali

ACCOUNTABILITY IN FIJI’S PROVINCIAL COUNCILS AND COMPANIES: THE CASE FOR LAU AND NAMOSI MASILINA TUILOA ROTUIVAQALI ACCOUNTABILITY IN FIJI’S PROVINCIAL COUNCILS AND COMPANIES: THE CASE FOR LAU AND NAMOSI by Masilina Tuiloa Rotuivaqali A thesis submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Commerce Copyright © 2012 by Masilina Tuiloa Rotuivaqali School of Accounting & Finance Faculty of Business & Economics The University of the South Pacific September, 2012 DECLARATION Statement by Author I, Masilina Tuiloa Rotuivaqali, declare that this thesis is my own work and that, to the best of my knowledge, it contains no material previously published, or substantially overlapping with material submitted for the award of any other degree at any institution, except where due acknowledgement is made in the text. Signature………………………………. Date……………………………… Name: Masilina Tuiloa Rotuivaqali Student ID No: S00001259 Statement by Supervisor The research in this thesis was performed under my supervision and to my knowledge is the sole work of Mrs. Masilina Tuiloa Rotuivaqali. Signature……………………………… Date………………………………... Name: Michael Millin White Designation: Professor in Accounting DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to my beloved daughters Adi Filomena Rotuisolia, Adi Fulori Rotuisolia and Adi Losalini Rotuisolia and to my niece and nephew, Masilina Tehila Tuiloa and Malakai Ebenezer Tuiloa. I hope this thesis will instill in them the desire to continue pursuing their education. As Nelson Mandela once said and I quote “Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world.” i ACKNOWLEDGEMENT The completion of this thesis owes so much from the support of several people and organisations. -

We Are Kai Tonga”

5. “We are Kai Tonga” The islands of Moala, Totoya and Matuku, collectively known as the Yasayasa Moala, lie between 100 and 130 kilometres south-east of Viti Levu and approximately the same distance south-west of Lakeba. While, during the nineteenth century, the three islands owed some allegiance to Bau, there existed also several family connections with Lakeba. The most prominent of the few practising Christians there was Donumailulu, or Donu who, after lotuing while living on Lakeba, brought the faith to Moala when he returned there in 1852.1 Because of his conversion, Donu was soon forced to leave the island’s principal village, Navucunimasi, now known as Naroi. He took refuge in the village of Vunuku where, with the aid of a Tongan teacher, he introduced Christianity.2 Donu’s home island and its two nearest neighbours were to be the scene of Ma`afu’s first military adventures, ostensibly undertaken in the cause of the lotu. Richard Lyth, still working on Lakeba, paid a pastoral visit to the Yasayasa Moala in October 1852. Despite the precarious state of Christianity on Moala itself, Lyth departed in optimistic mood, largely because of his confidence in Donu, “a very steady consistent man”.3 He observed that two young Moalan chiefs “who really ruled the land, remained determined haters of the truth”.4 On Matuku, which he also visited, all villages had accepted the lotu except the principal one, Dawaleka, to which Tui Nayau was vasu.5 The missionary’s qualified optimism was shattered in November when news reached Lakeba of an attack on Vunuku by the two chiefs opposed to the lotu. -

Severe Tc Gita (Cat4) Passes Just South of Ono

FIJI METEOROLOGICAL SERVICES GOVERNMENT OF THE REPUBLIC OF FIJI MEDIA RELEASE No.35 5pm, Tuesday 13 February 2018 SEVERE TC GITA (CAT4) PASSES JUST SOUTH OF ONO Severe TC Gita (Category 4) entered Fiji Waters this morning and passed just south of Ono-i- lau at around 1.30pm this afternoon. Hurricane force winds of 68 knots and maximum momentary gusts of 84 knots were recorded at Ono-i-lau at 2pm this afternoon as TC Gita tracked westward. Vanuabalavu also recorded strong and gusty winds (Table 1). Severe “TC Gita” was located near 21.2 degrees south latitude and 178.9 degrees west longitude or about 60km south-southwest of Ono-i-lau or 390km southeast of Kadavu at 3pm this afternoon. It continues to move westward at about 25km/hr and expected to continue on this track and gradually turn west-southwest. On its projected path, Severe TC Gita is predicted to be located about 140km west-southwest of Ono-i-lau or 300km southeast of Kadavu around 8pm tonight. By 2am tomorrow morning, Severe TC Gita is expected to be located about 240km west-southwest of Ono-i-lau and 250km southeast of Kadavu and the following warnings remains in force: A “Hurricane Warning” remains in force for Ono-i-lau and Vatoa; A “Storm Warning” remains in force for the rest of Southern Lau group; A “Gale Warning” remains in force for Matuku, Totoya, Moala , Kadavu and nearby smaller islands and is now in force for Lakeba and Nayau; A “Strong Wind Warning” remains in force for Central Lau Group, Lomaiviti Group, southern half of Viti Levu and is now in force for rest of Fiji. -

Setting Priorities for Marine Conservation in the Fiji Islands Marine Ecoregion Contents

Setting Priorities for Marine Conservation in the Fiji Islands Marine Ecoregion Contents Acknowledgements 1 Minister of Fisheries Opening Speech 2 Acronyms and Abbreviations 4 Executive Summary 5 1.0 Introduction 7 2.0 Background 9 2.1 The Fiji Islands Marine Ecoregion 9 2.2 The biological diversity of the Fiji Islands Marine Ecoregion 11 3.0 Objectives of the FIME Biodiversity Visioning Workshop 13 3.1 Overall biodiversity conservation goals 13 3.2 Specifi c goals of the FIME biodiversity visioning workshop 13 4.0 Methodology 14 4.1 Setting taxonomic priorities 14 4.2 Setting overall biodiversity priorities 14 4.3 Understanding the Conservation Context 16 4.4 Drafting a Conservation Vision 16 5.0 Results 17 5.1 Taxonomic Priorities 17 5.1.1 Coastal terrestrial vegetation and small offshore islands 17 5.1.2 Coral reefs and associated fauna 24 5.1.3 Coral reef fi sh 28 5.1.4 Inshore ecosystems 36 5.1.5 Open ocean and pelagic ecosystems 38 5.1.6 Species of special concern 40 5.1.7 Community knowledge about habitats and species 41 5.2 Priority Conservation Areas 47 5.3 Agreeing a vision statement for FIME 57 6.0 Conclusions and recommendations 58 6.1 Information gaps to assessing marine biodiversity 58 6.2 Collective recommendations of the workshop participants 59 6.3 Towards an Ecoregional Action Plan 60 7.0 References 62 8.0 Appendices 67 Annex 1: List of participants 67 Annex 2: Preliminary list of marine species found in Fiji. 71 Annex 3 : Workshop Photos 74 List of Figures: Figure 1 The Ecoregion Conservation Proccess 8 Figure 2 Approximate -

Tuesday-27Th November 2018

PARLIAMENT OF THE REPUBLIC OF FIJI PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES DAILY HANSARD TUESDAY, 27TH NOVEMBER, 2018 [CORRECTED COPY] C O N T E N T S Pages Minutes … … … … … … … … … … 10 Communications from the Chair … … … … … … … 10-11 Point of Order … … … … … … … … … … 11-12 Debate on His Excellency the President’s Address … … … … … 12-68 List of Speakers 1. Hon. J.V. Bainimarama Pages 12-17 2. Hon. S. Adimaitoga Pages 18-20 3. Hon. R.S. Akbar Pages 20-24 4. Hon. P.K. Bala Pages 25-28 5. Hon. V.K. Bhatnagar Pages 28-32 6. Hon. M. Bulanauca Pages 33-39 7. Hon. M.D. Bulitavu Pages 39-44 8. Hon. V.R. Gavoka Pages 44-48 9. Hon. Dr. S.R. Govind Pages 50-54 10. Hon. A. Jale Pages 54-57 11. Hon. Ro T.V. Kepa Pages 57-63 12. Hon. S.S. Kirpal Pages 63-64 13. Hon. Cdr. S.T. Koroilavesau Pages 64-68 Speaker’s Ruling … … … … … … … … … 68 TUESDAY, 27TH NOVEMBER, 2018 The Parliament resumed at 9.36 a.m., pursuant to adjournment. HONOURABLE SPEAKER took the Chair and read the Prayer. PRESENT All Honourable Members were present. MINUTES HON. LEADER OF THE GOVERNMENT IN PARLIAMENT.- Madam Speaker, I move: That the Minutes of the sittings of Parliament held on Monday, 26th November 2018, as previously circulated, be taken as read and be confirmed. HON. A.A. MAHARAJ.- Madam Speaker, I beg to second the motion. Question put Motion agreed to. COMMUNICATIONS FROM THE CHAIR Welcome I welcome all Honourable Members to the second sitting day of Parliament for the 2018 to 2019 session. -

Criminal Causelist Monday – 29/03/21 Suva Magistrate's Court No. 1 at 9.30Am

CRIMINAL CAUSELIST MONDAY – 29/03/21 SUVA MAGISTRATE’S COURT NO. 1 AT 9.30AM Parties Case No. Offence MENTION 1. State against Jesoni Takuca 285/20 Absconding Bail 2. State against Jesoni Tukuca 718/17 Theft 3. State against Savenaca Lewatabe [Ba] 106/20 Disobedience Of Lawful Order 4. State against Taione Lesumaisolomone [Lakeba] 65/20 Absconding Bail 5. State against Taione Lesumaisolomone [Lakeba] 30/18 Indecent Assault 6. State against Amol Chand 1601/11 Obtaining Financial Advantage By Deception 7. State against Peniasi Vata [Lautoka] 293/21 Theft 8. State against Sakeasi Lotawa [Ba] 96/21 Assault Causing Actual Bodily Harm 9. State against Jitendra Kumar [Tavua] 206/20 Failure To Comply With Orders 10. State against Timaleti Utovou 404/21 Absconding Bail RETURNABLE 11. State against Mikaele Valesi Kovelotu [Rotuma] 2/18 Criminal Trespass 12. State against Timaima Tawake 154/17 Theft 13. State against Irami Namataga EJ 13/15 Aggravated Burglary Theft CRIMINAL CAUSELIST MONDAY – 29/03/21 SUVA MAGISTRATE’S COURT NO. 2 AT 9.30AM Parties Case No. Offence MENTION 1. State against Ritesh Prasad 377/21 Theft 2. State against Onisimo Tokalaulevu 342/21 Failure To Comply With Orders 3. MOH against Foods (Pacific) Pte Limited 126/20 Prohibited Claim 4. State against Pio Penaia Nawaqavuli 166/21 Burglary Theft 5. State against Jack Edward Hiramatsu 1206/19 Forgery Adi Mara Rufina Qaranivalu Using Forged Documents Melikiseteki Wara Obtaining Financial Advantage By Deception Seini Pece Tadulala 6. State against Sylvia Kuar Sing 1433/18 Assault Causing Actual Bodily Harm 7. State against Anita Reddy 1702/18 Theft REVIEW 8. -

Researchspace@Auckland

http://researchspace.auckland.ac.nz ResearchSpace@Auckland Copyright Statement The digital copy of this thesis is protected by the Copyright Act 1994 (New Zealand). This thesis may be consulted by you, provided you comply with the provisions of the Act and the following conditions of use: • Any use you make of these documents or images must be for research or private study purposes only, and you may not make them available to any other person. • Authors control the copyright of their thesis. You will recognise the author's right to be identified as the author of this thesis, and due acknowledgement will be made to the author where appropriate. • You will obtain the author's permission before publishing any material from their thesis. To request permissions please use the Feedback form on our webpage. http://researchspace.auckland.ac.nz/feedback General copyright and disclaimer In addition to the above conditions, authors give their consent for the digital copy of their work to be used subject to the conditions specified on the Library Thesis Consent Form and Deposit Licence. CONNECTING IDENTITIES AND RELATIONSHIPS THROUGH INDIGENOUS EPISTEMOLOGY: THE SOLOMONI OF FIJI ESETA MATEIVITI-TULAVU A thesis in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY The University of Auckland Auckland, New Zealand 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract .................................................................................................................................. vi Dedication ............................................................................................................................ -

Indigenous Itaukei Worldview Prepared by Dr

Indigenous iTaukei Worldview Prepared by Dr. Tarisi Vunidilo Illustration by Cecelia Faumuina Author Dr Tarisi Vunidilo Tarisi is an Assistant Professor of Anthropology at the University of Hawaiʻi at Hilo, where she teaches courses on Indigenous museology and heritage management. Her current area of research is museology, repatriation and Indigenous knowledge and language revitalization. Tarisi Vunidilo is originally from Fiji. Her father, Navitalai Sorovi and mother, Mereseini Sorovi are both from the island of Kadavu, Southern Fiji. Tarisi was born and educated in Suva. Front image caption & credit Name: Drua Description: This is a model of a Fijian drua, a double hulled sailing canoe. The Fijian drua was the largest and finest ocean-going vessel which could range up to 100 feet in length. They were made by highly skilled hereditary canoe builders and other specialist’s makers for the woven sail, coconut fibre sennit rope and paddles. Credit: Commissioned and made by Alex Kennedy 2002, collection of Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, FE011790. Link: https://collections.tepapa.govt.nz/object/648912 Page | 2 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................................................... 4 SECTION 2: PREHISTORY OF FIJI .............................................................................................................. 5 SECTION 3: ITAUKEI SOCIAL STRUCTURE ............................................................................................... -

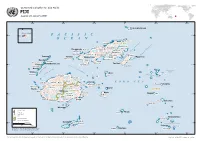

4348 Fiji Planning Map 1008

177° 00’ 178° 00’ 178° 30’ 179° 00’ 179° 30’ 180° 00’ Cikobia 179° 00’ 178° 30’ Eastern Division Natovutovu 0 10 20 30 Km 16° 00’ Ahau Vetauua 16° 00’ Rotuma 0 25 50 75 100 125 150 175 200 km 16°00’ 12° 30’ 180°00’ Qele Levu Nambouono FIJI 0 25 50 75 100 mi 180°30’ 20 Km Tavewa Drua Drua 0 10 National capital 177°00’ Kia Vitina Nukubasaga Mali Wainingandru Towns and villages Sasa Coral reefs Nasea l Cobia e n Pacific Ocean n Airports and airfields Navidamu Labasa Nailou Rabi a ve y h 16° 30’ o a C Natua r B Yanuc Division boundaries d Yaqaga u a ld Nabiti ka o Macuata Ca ew Kioa g at g Provincial boundaries Votua N in Yakewa Kalou Naravuca Vunindongoloa Loa R p Naselesele Roads u o Nasau Wailevu Drekeniwai Laucala r Yasawairara Datum: WGS 84; Projection: Alber equal area G Bua Bua Savusavu Laucala Denimanu conic: standard meridan, 179°15’ east; standard a Teci Nakawakawa Wailagi Lala w Tamusua parallels, 16°45’ and 18°30’ south. a Yandua Nadivakarua s Ngathaavulu a Nacula Dama Data: VMap0 and Fiji Islands, FMS 16, Lands & Y Wainunu Vanua Levu Korovou CakaudroveTaveuni Survey Dept., Fiji 3rd Edition, 1998. Bay 17° 00’ Nabouwalu 17° 00’ Matayalevu Solevu Northern Division Navakawau Naitaba Ngunu Viwa Nanuku Passage Bligh Water Malima Nanuya Kese Lau Group Balavu Western Division V Nathamaki Kanacea Mualevu a Koro Yacata Wayalevu tu Vanua Balavu Cikobia-i-lau Waya Malake - Nasau N I- r O Tongan Passage Waya Lailai Vita Levu Rakiraki a Kade R Susui T Muna Vaileka C H Kuata Tavua h E Navadra a Makogai Vatu Vara R Sorokoba Ra n Lomaiviti Mago -

P a C I F I C O C E

OCHA Regional Office for Asia Pacific FIJI Issued: 20 January 2008 177°E 178°E 179°E 180° 179°W 178°W Thikombia Island 177° Nalele Rotuma Island 16°S PACIFIC 16°S 12°30’ Rotuma Sumi OCEAN Namukalau Nambouono Vunivatu NORTHERN Nanduri Namboutini Nayarambale Napuka Yangganga Navindamu Labasa Nailou Yangganga Rabi Channel Korotasere Nakarambo Savu Sau Nawailevu Taveun i Mate i Vanuabalavu Riqold Channel Mbangasau t i Matei Yasawa a Yandua r Nggamea Vanua Levu t Qeleni Cicia S Ndenimanu o Nacula Ndaria o m o s Waiyevo Navotua Waisa m S o Matacawalevu Matathawa Levu Rave-rave Taveuni 17°S Yaqeta VATU-I-RA CHANNELThavanga 17°S Somosomo Navakawau UP RO Naviti G A W A EXPLORING S Waya S ISLES A Y Koro Nalauwaki NORT Thikombia BLIGH WATER Togow ere Koro HERN LAU Tavua Makongai GRO Nasau UP Nayavutoka Vanuakula Lautoka Navala Navai Ovalau KORO SEA Bureta Levuka Tu vu th a Tuvutha Mala WESTERN Nayavu Lawaki Malololailai Nadi Wairuarua Lovoni Bukuya Nairai Malolo Vunindawa Saweni Korovou EASTERN Momi Viti Levu CENTRAL Narewa Dromuna Ngau 18°S Naraiyawa Nayau Liku 18°S Namosi Nausori Bega Ngau Sigatoka Navua Vatukarasa SUVA e Levuka Lakemba ssag Pa qa Vanuavatu Be Waisomo Mbengga National Capital City, Town Moala Moala Major Airport River Namuka Llau Provincial Boundary Namuka International Boundary Vabea 0 20 40 Kilometers Kandavu 19°S Soso 19°S Nukuvou SOUTHERN LAU GROUP 0 20 40 Miles Kandavu Fulanga Ongea Projection: World Cylindrical Equal Area Nasau Andako Matuku Monothaki Map data sources: Global Discovery, FAO 177°E 178°E 179°E 180° 179°W 178°W The names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations Map Ref: OCHA_FJI_Country_v1_080120. -

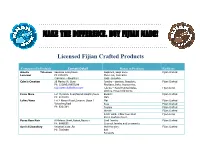

Make the Difference. Buy Fijian Made! ……………………………………………………….…

…….…………………………………………………....…. MAKE THE DIFFERENCE. BUY FIJIAN MADE! ……………………………………………………….…. Licensed Fijian Crafted Products Companies/Individuals Contact Detail Range of Products Emblems Amelia Yalosavu Sawarua Lokia,Rewa Saqamoli, Saqa Vonu Fijian Crafted Lesumai Ph:8332375 Mua i rua, Ramrama (Sainiana – daughter) Saqa -gusudua Cabe’s Creation 20 Marino St, Suva Jewelry - earrings, Bracelets, Fijian Crafted Ph: 3318953/9955299 Necklace, Belts, Accessories. [email protected] Fabrics – Hand Painted Sulus, Fijian Sewn Clothes, Household Items Finau Mara Lot 15,Salato Road,Namdi Heights,Suva Baskets Fijian Crafted Ph: 9232830 Mats Lolive Vana Lot 2 Navani Road,Suvavou Stage 1 Mat Fijian Crafted Votualevu,Nadi Kuta Fijian Crafted Ph: 9267384 Topiary Fijian Crafted Wreath Fijian Crafted Patch work- Pillow Case Bed Fijian Sewn Sheet Cushion Cover. Paras Ram Nair 6 Matana Street,Nakasi,Nausori Shell Jewelry Fijian Crafted Ph: 9049555 Coconut Jewelry and ornaments Seniloli Jewellery Veiseisei,Vuda ,Ba Wall Hanging Fijian Crafted Ph: 7103989 Belt Pendants Makrava Luise Lot 4,Korovuba Street,Nakasi Hand Bags Fijian Crafted Ph: 3411410/7850809 Fans [email protected] Flowers Selai Buasala Karova Settlement,Laucala bay Masi Fijian Crafted Ph:9213561 Senijiuri Tagi c/-Box 882, Nausori Iri-Buli Fijian Crafted Vai’ala Teruka Veisari Baskets, Place Mats Fijian Crafted Ph:9262668/3391058 Laundary Baskets Trays and Fruit baskets Jonaji Cama Vishnu Deo Road, Nakasi Carving – War clubs, Tanoa, Fijian Crafted PH: 8699986 Oil dish, Fruit Bowl Unik -

Republic of Fiji: the State of the World's Forest Genetic Resources

REPUBLIC OF FIJI This country report is prepared as a contribution to the FAO publication, The Report on the State of the World’s Forest Genetic Resources. The content and the structure are in accordance with the recommendations and guidelines given by FAO in the document Guidelines for Preparation of Country Reports for the State of the World’s Forest Genetic Resources (2010). These guidelines set out recommendations for the objective, scope and structure of the country reports. Countries were requested to consider the current state of knowledge of forest genetic diversity, including: Between and within species diversity List of priority species; their roles and values and importance List of threatened/endangered species Threats, opportunities and challenges for the conservation, use and development of forest genetic resources These reports were submitted to FAO as official government documents. The report is presented on www. fao.org/documents as supportive and contextual information to be used in conjunction with other documentation on world forest genetic resources. The content and the views expressed in this report are the responsibility of the entity submitting the report to FAO. FAO may not be held responsible for the use which may be made of the information contained in this report. STATE OF THE FOREST GENETIC RESOURCES IN FIJI Department of Forests Ministry of Fisheries and Forests for The Republic of Fiji Islands and the Secreatriat of Pacific Communities (SPC) State of the Forest Genetic Resources in Fiji _____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Table of Contents Executve Summary ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..…….. 5 Introduction ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..…….. 6 Chapter 1: The Current State of the Forest Genetic Resources in Fiji ………………………………………………………………….…….