Exploratory Serial Narratives Récits Sériels Exploratoires

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

68Th EMMY® AWARDS NOMINATIONS for Programs Airing June 1, 2015 – May 31, 2016

EMBARGOED UNTIL 8:40AM PT ON JULY 14, 2016 68th EMMY® AWARDS NOMINATIONS For Programs Airing June 1, 2015 – May 31, 2016 Los Angeles, CA, July 14, 2016– Nominations for the 68th Emmy® Awards were announced today by the Television Academy in a ceremony hosted by Television Academy Chairman and CEO Bruce Rosenblum along with Anthony Anderson from the ABC series black-ish and Lauren Graham from Parenthood and the upcoming Netflix revival, Gilmore Girls. "Television dominates the entertainment conversation and is enjoying the most spectacular run in its history with breakthrough creativity, emerging platforms and dynamic new opportunities for our industry's storytellers," said Rosenblum. “From favorites like Game of Thrones, Veep, and House of Cards to nominations newcomers like black-ish, Master of None, The Americans and Mr. Robot, television has never been more impactful in its storytelling, sheer breadth of series and quality of performances by an incredibly diverse array of talented performers. “The Television Academy is thrilled to once again honor the very best that television has to offer.” This year’s Drama and Comedy Series nominees include first-timers as well as returning programs to the Emmy competition: black-ish and Master of None are new in the Outstanding Comedy Series category, and Mr. Robot and The Americans in the Outstanding Drama Series competition. Additionally, both Veep and Game of Thrones return to vie for their second Emmy in Outstanding Comedy Series and Outstanding Drama Series respectively. While Game of Thrones again tallied the most nominations (23), limited series The People v. O.J. Simpson: American Crime Story and Fargo received 22 nominations and 18 nominations respectively. -

S:\Civil\Clark Class Cert.Wpd

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT MIDDLE DISTRICT OF NORTH CAROLINA SABRINA CLARK, on behalf of ) herself and a class of those ) similarly situated, ) ) Plaintiffs, ) v. ) ) MEMORANDUM OPINION ) AND RECOMMENDATION WELLS FARGO FINANCIAL, INC., ) WELLS FARGO FINANCIAL ) 1:08CV343 NORTH CAROLINA, INC., ) d/b/a WELLS FARGO FINANCIAL ) and WELLS FARGO FINANCIAL ) ACCEPTANCE, and DOES 1-50, ) ) Defendants. ) This matter is before the court on a motion to dismiss Plaintiffs’ collective action and class action claims or, alternatively, for summary adjudication by Defendants Wells Fargo Financial, Inc. and Wells Fargo Financial North Carolina, Inc. (collectively “Wells Fargo” or “Defendants”) (docket no. 11), and on Plaintiffs’ motion to stay the deadline for filing a motion for class certification (docket no. 19). The parties have responded in opposition to the respective motions, and the matter is ripe for disposition. Furthermore, the parties have not consented to the jurisdiction of the magistrate judge. The motions must, therefore, be dealt with by way of recommendation. For the following reasons, it will be recommended that the court deny Defendants’ motion to dismiss and grant Plaintiffs’ motion to stay. Case 1:08-cv-00343-NCT-WWD Document 28 Filed 10/30/08 Page 1 of 20 Background Plaintiff Sabrina Clark filed this purported class action on behalf of herself and others similarly situated, based on Wells Fargo’s alleged failure to pay overtime to Plaintiffs in accordance with the Fair Labor Standards Act (“FLSA”), 29 U.S.C. § 210 et seq.1 Plaintiffs seek to have this court grant a motion for a conditional collective class action under section 216(b) of the FLSA. -

Walpole Public Library DVD List A

Walpole Public Library DVD List [Items purchased to present*] Last updated: 9/17/2021 INDEX Note: List does not reflect items lost or removed from collection A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z Nonfiction A A A place in the sun AAL Aaltra AAR Aardvark The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, ABB V.1 vol.1 The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, ABB V.2 vol.2 The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, ABB V.3 vol.3 The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, ABB V.4 vol.4 ABE Aberdeen ABO About a boy ABO About Elly ABO About Schmidt ABO About time ABO Above the rim ABR Abraham Lincoln vampire hunter ABS Absolutely anything ABS Absolutely fabulous : the movie ACC Acceptable risk ACC Accepted ACC Accountant, The ACC SER. Accused : series 1 & 2 1 & 2 ACE Ace in the hole ACE Ace Ventura pet detective ACR Across the universe ACT Act of valor ACT Acts of vengeance ADA Adam's apples ADA Adams chronicles, The ADA Adam ADA Adam’s Rib ADA Adaptation ADA Ad Astra ADJ Adjustment Bureau, The *does not reflect missing materials or those being mended Walpole Public Library DVD List [Items purchased to present*] ADM Admission ADO Adopt a highway ADR Adrift ADU Adult world ADV Adventure of Sherlock Holmes’ smarter brother, The ADV The adventures of Baron Munchausen ADV Adverse AEO Aeon Flux AFF SEAS.1 Affair, The : season 1 AFF SEAS.2 Affair, The : season 2 AFF SEAS.3 Affair, The : season 3 AFF SEAS.4 Affair, The : season 4 AFF SEAS.5 Affair, -

Fargo Tannery

/THE SOME ECCENTRIC FuNu .al What is Womanfs < An enormous crowd gathered « ..Chester, England, a few months ap -to witness the funeral of an electrics Beauty but Health? engineer, who w bb carried to the cen, etery in a coffin that had been labon And the Basis of Her Health and ou.sly constructed by himself out ol Vigor Lies in the Careful Reg To the Merit o f Lydia E. Pink 4,000 match boxes. These, with their ulation of the Bowels. ham’s Vegetable Com tops visible and advertising their re I f woman’s beauty depended upon spective makers, were varnished over cosmetics, every woman would be a pound during Change and strengthened Inside with wood. * ✓ picture of loveliness. But beauty lies o f Life. On the coffin was placed an electric deeper than that It lies in health. In •battery. the majority of cases the basis of Ancient Lindisfarne Castle Some years ago a maiden lady died health, and the cause of sickness, can Streator, H .—" I Bhallalways praise at Calemis-sur-Lys, in France, who be traced to the action of the bowels. Lydia E. Pinkham’s Vegetable Com was reported to have been a champi(#t The headaches, the lassitude, the pound wherever I snuff taker. She enjoyed singularly sallow akin and the luBterless eyes are go. It baa done me good health, retained all her mental usually due to constipation. So many so much good at faculties, and died at a ripe old age. things that women do habitually con Change o f Life, and Her funeral was most extraordinary. -

STEM Skill Booster: Knight Training Supplies

STEM Skill Booster: Knight Training Supplies Craft Sticks (6) Rubber Bands (5) Plastic Spoon Pom-Pom Ball Paperclip Glue (not included) Markers or Crayons (not included) Scissors (not included) Optional – Cereal Box or Cardboard (not included) Instructions Can you become a Knight of the West Fargo Public Library? Complete the packet to test your skills. We have devised a number of activities for you to complete and gain your knighthood. You will design your Coat of Arms, build a castle, construct a catapult and encounter dragons. Good luck! STEM Concepts Construct – to build or create Engineer – a person who design and builds machines, systems or structures Four Forces of Flight – the four forces that help an airplane (or object) fly Lift – holds the airplane in the air, often created by the wings Thrust – moves an aircraft in the direction of motion, often created by an engine or propeller Drag – acts opposite to the direction of motion or slows down an object Weight – caused by gravity, bring objects down Coat of Arms A Coat of Arms was the image or icon of a family in medieval times. Colors and symbols were chosen to represent different strengths and the history of the family. Design your own Coat in the drawing below. Choose colors and images to represent what you think a valiant knight should be or to represent your family. Shield Often a Coat of Arms is worn on a knight’s shield. For an added challenge build your shield and include your Coat of Arms. 1. Draw the shape of a shield onto something sturdy you can cut, like cardboard or an empty cereal box. -

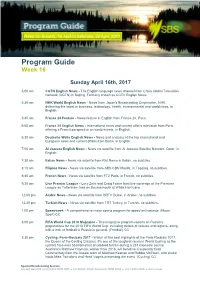

Program Guide Week 16

Week 16: Sunday, 16 April to Saturday, 22 April, 2017 Program Guide Week 16 Sunday April 16th, 2017 5:00 am CGTN English News - The English language news channel from China Global Television Network (CGTN) in Beijing. Formerly known as CCTV English News. 5:30 am NHK World English News - News from Japan's Broadcasting Corporation, NHK, delivering the latest in business, technology, health, environmental and world news, in English. 5:45 am France 24 Feature - News feature in English from France 24, Paris. 6:00 am France 24 English News - International news and current affairs television from Paris, offering a French perspective on world events, in English. 6:30 am Deutsche Welle English News - News and analysis of the top international and European news and current affairs from Berlin, in English. 7:00 am Al Jazeera English News - News via satellite from Al Jazeera Satellite Network, Qatar, in English. 7:30 am Italian News - News via satellite from RAI Rome in Italian, no subtitles. 8:10 am Filipino News - News via satellite from ABS-CBN Manila, in Tagalog, no subtitles. 8:40 am French News - News via satellite from FT2 Paris, in French, no subtitles. 9:30 am Live Premier League - Lucy Zelic and Craig Foster host live coverage of the Premiere League as Tottenham take on Bournemouth at White Hart Lane. 12:00 pm Arabic News - News via satellite from DRTV Dubai, in Arabic, no subtitles. 12:30 pm Turkish News - News via satellite from TRT Turkey, in Turkish, no subtitles. 1:00 pm Speedweek - A comprehensive motor sports program for speed enthusiasts. -

Press Contacts for the Television Academy: 818-264

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Post-awards presentation (approximately 7:00PM, PDT) September 10, 2016 WINNERS OF THE 68th CREATIVE ARTS EMMY® AWARDS ANNOUNCED (Los Angeles, Calif. - September 10, 2016) The Television Academy tonight presented the first of its two 2016 Creative Arts Emmy® Awards ceremonies for programs and individual achievements at the Microsoft Theater in Los Angeles. This initial awards ceremony of the 68th Emmys honored guest performers on television drama series and comedy series, as well as the many talented artists and craftspeople behind the scenes who create television excellence. Executive produced by Bob Bain, this year’s Creative Arts Awards featured an array of notable presenters, among them Rachel Bloom, Mel B, Joanne Froggatt, Michael Kelly, Margo Martindale, Laurie Metcalf, Bob Newhart and Bradley Whitford. For more information, visit Emmys.com PRESS CONTACTS FOR THE TELEVISION ACADEMY: Jim Yeager breakwhitelight public relations [email protected] 818-264-6812 Stephanie Goodell breakwhitelight public relations [email protected] 818-462-1150 TELEVISION ACADEMY 2016 CREATIVE ARTS EMMY AWARDS – SATURDAY The awards, as tabulated by the independent accounting firm of Ernst & Young LLP, were distributed as follows: Program Individual Total HBO - 11 11 FX Networks 1 9 10 PBS - 5 5 Amazon - 4 4 CBS 1 1 2 Showtime - 2 2 ABC 1 - 1 AMC - 1 1 Cartoon Network 1 - 1 CNN - 1 1 Comedy Central 1 - 1 CW - 1 1 NBC - 1 1 Netflix - 1 1 Nickelodeon - 1 1 Oculus Platform 1 - 1 Starz - 1 1 USA - 1 1 A complete list of all awards presented tonight is attached. The final page of the attached list includes a recap of all programs with multiple awards. -

DVD LISTINGS Dec. 2019

DVD LISTINGS Dec. 2019 New DESCRIPTION # 1 21 2 10,000 BC 3 10TH KINGDOM 4 12 ANGRY MEN 5 13 GOING ON 30 6 17 AGAIN 7 20 BLAZING WESTERN MOVIES 8 20 YEARS WITH DOLPHINS 9 200 CLASSIC CARTOONS 10 2001 - A SPACE ODYSSEY 11 2010 - YEAR WE MADE CONTACT, THE 12 25TH HOUR 13 27 DRESSES 14 28 DAYS 15 3 DAYS OF THE CONDOR 16 40 DAYS AND 40 NIGHTS 17 50 FIRST DATES 18 6TH DAY, THE 19 6TH DAY, THE 20 A DOG'S WAY HOME 21 ABOUT SCHMIDT 22 ABYSS, THE 23 ACADEMY AWARD WINNER 24 ACCIDENTAL SPY 25 ADAM 26 ADVISE AND CONSENT 27 AFTER THE SUNSET 28 AGE OF CONSENT 29 AGE OF INNOCENCE 30 AGENT HAMILTON 31 AGNES BROWN 32 AIR FORCE ONE 33 AIRPLANE 34 ALAMO 35 ALEX CROSS 36 ALFRED HITCHOCK TV SERIES SET 37 ALI 38 ALICE IN WONDERLAND 39 ALIEN, THE 40 ALIVE 41 ALL ABOUT EVE 42 ALL THE PRSIDENT MEN 43 ALONG CAME POLLY 44 ALWAYS 45 AMADEUS 46 AMAZING ADVENTURE (B/W) 47 AMAZING MYSTERIES OF ANCIENT PROPHETS 48 AMELIE PHSC Video Library Inventory List 1 - 24 9/1/2020 1:57 PM DVD LISTINGS Dec. 2019 New DESCRIPTION # 49 AMERICAN HISTORY X 50 AMERICAN IN PARIS, AN 51 AMERICAN PRESIDENT, THE 52 AMERICA'S MOST SCENIC DRIVES 53 AMERICA'S NATIONAL TREASURES 54 AMERICA'S SWEETHEARTS 55 ANALYSE THAT 56 ANATOMY OF A MURDER 57 AND THE BAND PLAYED ON 58 ANDROMEDA STRAIN, THE 59 ANDY WILLIAMS CHRISTMAS SHOW 60 ANGEL AND THE BADMAN 61 ANGEL ON MY SHOULDER 62 ANGER MANAGEMENT 63 ANGRY RED PLANET, THE 64 ANNIE HALL 65 ANSEL ADAMS 66 ANTWONE FISHER 67 ANY GIVEN SUNDAY 68 APARTMENT, THE 69 APOCALYPSE NOW 70 APPALOOSA 71 ARSENIC AND OLD LACE 72 ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE (AI) 73 AS GOOD AS IT GETS 74 ASTRONAUT FARMER 75 ATONEMENT 76 AUGUST RUSH 77 AUGUST: OSAGE COUNTY 78 AUSTRALIA 79 AUTHOR 80 AUTHORS ANONYMOUS 81 AUTUMN IN NEW YORK 82 AVIATOR, THE 83 AVP-ALIENS VS. -

Nomination Press Release Award Year: 2016

Nomination Press Release Award Year: 2016 Outstanding Character Voice-Over Performance Family Guy • Pilling Them Softly • FOX • 20th Century Fox Television Seth MacFarlane as Peter Griffin, Stewie Griffin, Brian Griffin, Glenn Quagmire, Dr. Hartman, Tom Tucker, Mr. Spacely South Park • Stunning and Brave • Comedy Central • Central Productions Trey Parker as PC Principal, Cartman South Park • Tweek x Craig • Comedy Central • Central Productions Matt Stone as Craig Tucker, Tweek, Thomas Tucker SuperMansion • Puss in Books • Crackle • Stoopid Buddy Stoodios Keegan-Michael Key as American Ranger, Sgt. Agony SuperMansion • The Inconceivable Escape of Dr. Devizo • Crackle • Stoopid Buddy Stoodios Chris Pine as Dr. Devizo, Robo-Dino Outstanding Animated Program Archer • The Figgis Agency • FX Networks • FX Studios Bob's Burgers • The Horse Rider-er • FOX • Bento Box Entertainment Phineas and Ferb Last Day of Summer • Disney XD • Disney Television Animation The Simpsons • Halloween of Horror • FOX • Gracie Films in association with 20th Century Fox Television South Park • You're Not Yelping • Comedy Central • Central Productions Outstanding Short Form Animated Program Adventure Time • Hall of Egress • Cartoon Network • Cartoon Network Studios The Powerpuff Girls • Once Upon A Townsville • Cartoon Network • Cartoon Network Studios Robot Chicken • Robot Chicken Christmas Special: The X-Mas United • Adult Swim • Stoopid Buddy Stoodios SpongeBob SquarePants • Company Picnic • Nickelodeon • Nickelodeon Steven Universe • The Answer • Cartoon Network -

Alexandru Ioan Cuza

LINGUACULTURE 1, 2016 “THIS IS A […] STORY;”” THE REFUSAL OF A MASTER TEXT IN NOAH HAWLEY’S FARGO ALLEN H. REDMON Texas A&M University Central Texas, USA Abstract Each episode of Noah Hawley’s first two seasons of Fargo begins with the same claim: “this is a true story.” The claim might invite the formation of what Thomas Leitch (2007) calls a “privileged master text,” except that Hawley undermines the creation of such a text in at least two ways. On the one hand, Hawley uses his truth claim as a way to direct his audience into the film he is adapting – Joel and Ethan Coen’s (1996) film by the same name. Hawley ensures throughout his first season that those who know or who come-to-know the Coens’ work will recognize his story as an extension of the Coens’s world. Hawley references the Coens’ world so much that his audience is never entirely outside the Coens’ universe, and certainly not in any world a story based on a true event might pretend to occupy. At the same time, Hawley allows different speakers to make the opening truth claim by the end of his second season, which further prevents his truth assertion from locating viewers in any actual world. Hawley’s second move reveals that true stories are always subjective stories, which means they are always constructed stories. In this way, a true story is no more definitive than any other story. All stories are, in keeping with Jorge Luis Borges’ attitude toward definitive texts, only a draft or a version of a story. -

National Register of Historic Places Single Property Listings Illinois

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES SINGLE PROPERTY LISTINGS ILLINOIS FINDING AID One LaSalle Street Building (One North LaSalle), Cook County, Illinois, 99001378 Photo by Susan Baldwin, Baldwin Historic Properties Prepared by National Park Service Intermountain Region Museum Services Program Tucson, Arizona May 2015 National Register of Historic Places – Single Property Listings - Illinois 2 National Register of Historic Places – Single Property Listings - Illinois Scope and Content Note: The National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) is the official list of the Nation's historic places worthy of preservation. Authorized by the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, the National Park Service's National Register of Historic Places is part of a national program to coordinate and support public and private efforts to identify, evaluate, and protect America's historic and archeological resources. - From the National Register of Historic Places site: http://www.nps.gov/nr/about.htm The Single Property listing records from Illinois are comprised of nomination forms (signed, legal documents verifying the status of the properties as listed in the National Register) photographs, maps, correspondence, memorandums, and ephemera which document the efforts to recognize individual properties that are historically significant to their community and/or state. Arrangement: The Single Property listing records are arranged by county and therein alphabetically by property name. Within the physical files, researchers will find the records arranged in the following way: Nomination Form, Photographs, Maps, Correspondence, and then Other documentation. Extent: The NRHP Single Property Listings for Illinois totals 43 Linear Feet. Processing: The NRHP Single Property listing records for Illinois were processed and cataloged at the Intermountain Region Museum Services Center by Leslie Matthaei, Jessica Peters, Ryan Murray, Caitlin Godlewski, and Jennifer Newby. -

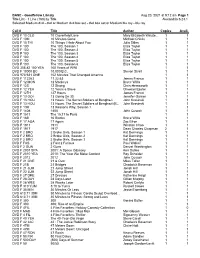

Goodfellow Library 1 Page Aug 20, 2021 at 9:12 Am Title List

BASE - Goodfellow Library Aug 20, 2021 at 9:12 am 1 Page Title List - 1 Line (160) by Title Alexandria 6.23.1 Selected:Medium dvd - dvd or Medium dvd box set - dvd box set or Medium blu ray - blu ray Call # Title Author Copies Avail. DVD F 10 CLO 10 Cloverfield Lane Mary Elizabeth Winste... 1 1 DVD F 10M 10 Minutes Gone Michael Chiklis 1 1 DVD F 10 THI 10 Things I Hate About You Julia Stiles 1 1 DVD F 100 The 100, Season 1 Eliza Taylor 1 1 DVD F 100 The 100, Season 2 Eliza Taylor 1 1 DVD F 100 The 100, Season 3 Eliza Taylor 1 1 DVD F 100 The 100, Season 4 Eliza Taylor 1 1 DVD F 100 The 100, Season 5 Eliza Taylor 1 1 DVD F 100 The 100, Season 6 Eliza Taylor 1 1 DVD 355.82 100 YEA 100 Years of WWI 1 1 DVD F 10000 BC 10,000 B.C. Steven Strait 1 1 DVD 973.931 ONE 102 Minutes That Changed America 1 1 DVD F 112263 11.22.63 James Franco 1 1 DVD F 12 MON 12 Monkeys Bruce Willis 1 1 DVD F 12S 12 Strong Chris Hemsworth 1 1 DVD F 12 YEA 12 Years a Slave Chiwetel Ejiofor 1 1 DVD F 127H 127 Hours James Franco 1 1 DVD F 13 GOI 13 Going On 30 Jennifer Garner 1 1 DVD F 13 HOU 13 Hours: The Secret Soldiers of Benghazi John Krasinski 1 1 DVD F 13 HOU 13 Hours: The Secret Soldiers of Benghazi (B..