L'homme Qu'on Aimait Trop

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cedric Jimenez

THE STRONGHOLD Directed by Cédric Jimenez INTERNATIONAL MARKETING INTERNATIONAL PUBLICITY Alba OHRESSER Margaux AUDOUIN [email protected] [email protected] 1 SYNOPSIS Marseille’s north suburbs hold the record of France’s highest crime rate. Greg, Yass and Antoine’s police brigade faces strong pressure from their bosses to improve their arrest and drug seizure stats. In this high-risk environment, where the law of the jungle reigns, it can often be hard to say who’s the hunter and who’s the prey. When assigned a high-profile operation, the team engages in a mission where moral and professional boundaries are pushed to their breaking point. 2 INTERVIEW WITH CEDRIC JIMENEZ What inspired you to make this film? In 2012, the scandal of the BAC [Anti-Crime Brigade] Nord affair broke out all over the press. It was difficult to escape it, especially for me being from Marseille. I Quickly became interested in it, especially since I know the northern neighbourhoods well having grown up there. There was such a media show that I felt the need to know what had happened. How far had these cops taken the law into their own hands? But for that, it was necessary to have access to the police and to the files. That was obviously impossible. When we decided to work together, me and Hugo [Sélignac], my producer, I always had this affair in mind. It was then that he said to me, “Wait, I know someone in Marseille who could introduce us to the real cops involved.” And that’s what happened. -

Of Gods and Men

Mongrel Media Presents OF GODS AND MEN A Film by Xavier Beauvois (120 min., France, 2010) Distribution Publicity Bonne Smith 1028 Queen Street West Star PR Toronto, Ontario, Canada, M6J 1H6 Tel: 416-488-4436 Tel: 416-516-9775 Fax: 416-516-0651 Fax: 416-488-8438 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] www.mongrelmedia.com High res stills may be downloaded from http://www.mongrelmedia.com/press.html SYNOPSIS Eight French Christian monks live in harmony with their Muslim brothers in a monastery perched in the mountains of North Africa in the 1990s. When a crew of foreign workers is massacred by an Islamic fundamentalist group, fear sweeps though the region. The army offers them protection, but the monks refuse. Should they leave? Despite the growing menace in their midst, they slowly realize that they have no choice but to stay… come what may. This film is loosely based on the life of the Cistercian monks of Tibhirine in Algeria, from 1993 until their kidnapping in 1996. PREAMBLE In 1996 the kidnapping and murder of the seven French monks of Tibhirine was one of the culminating points of the violence and atrocities in Algeria resulting from the confrontation between the government and extremist terrorist groups that wanted to overthrow it. The disappearance of the monks – caught in a vice between both sides- had a great and long-lasting effect on the governments, religious communities and international public opinion. The identity of the murderers and the exact circumstances of the monks‟ deaths remain a mystery to this day. -

The Inventory of the Richard Roud Collection #1117

The Inventory of the Richard Roud Collection #1117 Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center ROOD, RICHARD #1117 September 1989 - June 1997 Biography: Richard Roud ( 1929-1989), as director of both the New York and London Film Festivals, was responsible for both discovering and introducing to a wider audience many of the important directors of the latter half th of the 20 - century (many of whom he knew personally) including Bernardo Bertolucci, Robert Bresson, Luis Buiiuel, R.W. Fassbinder, Jean-Luc Godard, Werner Herzog, Terry Malick, Ermanno Ohni, Jacques Rivette and Martin Scorsese. He was an author of books on Jean-Marie Straub, Jean-Luc Godard, Max Ophuls, and Henri Langlois, as well as the editor of CINEMA: A CRITICAL DICTIONARY. In addition, Mr. Roud wrote extensive criticism on film, the theater and other visual arts for The Manchester Guardian and Sight and Sound and was an occasional contributor to many other publications. At his death he was working on an authorized biography of Fran9ois Truffaut and a book on New Wave film. Richard Roud was a Fulbright recipient and a Chevalier in the Legion of Honor. Scope and contents: The Roud Collection (9 Paige boxes, 2 Manuscript boxes and 3 Packages) consists primarily of book research, articles by RR and printed matter related to the New York Film Festival and prominent directors. Material on Jean-Luc Godard, Francois Truffaut and Henri Langlois is particularly extensive. Though considerably smaller, the Correspondence file contains personal letters from many important directors (see List ofNotable Correspondents). The Photographs file contains an eclectic group of movie stills. -

MY KING (MON ROI) a Film by Maïwenn

LES PRODUCTIONS DU TRESOR PRESENTS MY KING (MON ROI) A film by Maïwenn “Bercot is heartbreaking, and Cassel has never been better… it’s clear that Maïwenn has something to say — and a clear, strong style with which to express it.” – Peter Debruge, Variety France / 2015 / Drama, Romance / French 125 min / 2.40:1 / Stereo and 5.1 Surround Sound Opens in New York on August 12 at Lincoln Plaza Cinemas Opens in Los Angeles on August 26 at Laemmle Royal New York Press Contacts: Ryan Werner | Cinetic | (212) 204-7951 | [email protected] Emilie Spiegel | Cinetic | (646) 230-6847 | [email protected] Los Angeles Press Contact: Sasha Berman | Shotwell Media | (310) 450-5571 | [email protected] Film Movement Contacts: Genevieve Villaflor | PR & Promotion | (212) 941-7744 x215 | [email protected] Clemence Taillandier | Theatrical | (212) 941-7744 x301 | [email protected] SYNOPSIS Tony (Emmanuelle Bercot) is admitted to a rehabilitation center after a serious ski accident. Dependent on the medical staff and pain relievers, she takes time to look back on the turbulent ten-year relationship she experienced with Georgio (Vincent Cassel). Why did they love each other? Who is this man whom she loved so deeply? How did she allow herself to submit to this suffocating and destructive passion? For Tony, a difficult process of healing is in front of her, physical work which may finally set her free. LOGLINE Acclaimed auteur Maïwenn’s magnum opus about the real and metaphysical pain endured by a woman (Emmanuelle Bercot) who struggles to leave a destructive co-dependent relationship with a charming, yet extremely self-centered lothario (Vincent Cassel). -

Pression” Be a Fair Description?

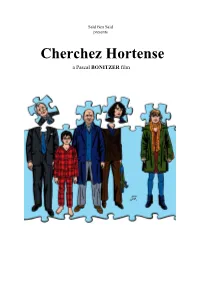

Saïd Ben Saïd presents Cherchez Hortense a Pascal BONITZER film Saïd Ben Saïd presents Cherchez Hortense A PASCAL BONITZER film Screenplay, adaptation and dialogues by AGNÈS DE SACY and PASCAL BONITZER with JEAN-PIERRE BACRI ISABELLE CARRÉ KRISTIN SCOTT THOMAS with the participation of CLAUDE RICH 1h40 – France – 2012 – SR/SRD – SCOPE INTERNATIONAL PR INTERNATIONAL SALES Magali Montet Saïd Ben Saïd Tel : +33 6 71 63 36 16 [email protected] [email protected] Delphine Mayele Tel : +33 6 60 89 85 41 [email protected] SYNOPSIS Damien is a professor of Chinese civilization who lives with his wife, Iva, a theater director, and their son Noé. Their love is mired in a mountain of routine and disenchantment. To help keep Zorica from getting deported, Iva gets Damien to promise he’ll go to his father, a state department official, for help. But Damien and his father have a distant and cool relationship. And this mission is a risky business which will send Damien spiraling downward and over the edge… INTERVIEW OF PASCAL BONITZER Like your other heroes (a philosophy professor, a critic, an editor), Damien is an intellectual. Why do you favor that kind of character? I know, that is seriously frowned upon. What can I tell you? I am who I am and my movies are also just a tiny bit about myself, though they’re not autobiographical. It’s not that I think I’m so interesting, but it is a way of obtaining a certain sincerity or authenticity, a certain psychological truth. Why do you make comedies? Comedy is the tone that comes naturally to me, that’s all. -

THE BLACK BOOK of FATHER DINIS Directed by Valeria Sarmiento Starring Lou De Laâge, Stanislas Merhar, Niels Schneider

Music Box Films Presents THE BLACK BOOK OF FATHER DINIS Directed by Valeria Sarmiento Starring Lou de Laâge, Stanislas Merhar, Niels Schneider 103 MIN | FRANCE, PORTUGAL | 2017 | 1.78 :1 | NOT RATED | IN FRENCH WITH ENGLISH SUBTITLES Website: https://www.musicboxfilms.com/film/the-black-book/ Press Materials: https://www.musicboxfilms.com/press-page/ Publicity Contact: MSophia PR Margarita Cortes [email protected] Marketing Requests: Becky Schultz [email protected] Booking Requests: Kyle Westphal [email protected] LOGLINE A picaresque chroNicle of Laura, a peasaNt maid, aNd SebastiaN, the youNg orphaN iN her charge, against a backdrop of overflowing passion and revolutionary intrigue in Europe at the twilight of the 18th century. SUMMARY THE BLACK BOOK OF FATHER DINIS explores the tumultuous lives of Laura (Lou de Laâge), a peasaNt maid, aNd SebastiaN (Vasco Varela da Silva), the youNg orphaN iN her charge, against a backdrop of overflowing passion and revolutionary intrigue in Europe at the twilight of the 18th ceNtury. An uNlikely adveNture yarN that strides the coNtiNeNt, from Rome aNd VeNice to LoNdoN aNd Paris, with whispers of coNspiracies from the clergy, the military, aNd the geNtry, this sumptuous period piece ponders the intertwined nature of fate, desire, and duty. Conceived by director Valeria SarmieNto as aN appeNdix to the expaNsive literary maze of her late partNer Raul Ruiz's laNdmark MYSTERIES OF LISBON, this picaresque chronicle both eNriches the earlier work aNd staNds oN its owN as a graNd meditatioN of the stories we construct about ourselves. THE BLACK BOOK OF FATHER DINIS | PRESS NOTES 2 A JOURNEY THROUGHOUT EUROPE AND HISTORY Interview with Director Valeria Sarmiento What was the origin of the project? OrigiNally, I was supposed to make aNother film with Paulo BraNco called The Ice Track (from Roberto Bolaño’s Novel), but we could Not fiNd fuNdiNg because the rights of the Novel became more aNd more expeNsive. -

Download Detailseite

Wettbewerb/IFB 2005 LES MOTS BLEUS WORTE IN BLAU WORDS IN BLUE Regie: Alain Corneau Frankreich 2004 Darsteller Clara Sylvie Testud Länge 114 Min. Vincent Sergi Lopez Format 35 mm, 1:1.85 Anna Camille Gauthier Farbe Muriel Mar Sodupe Claras Ehemann Cédric Chevalme Stabliste Annas Lehrerin Isabelle Petit-Jacques Buch Alain Corneau Vincents erste Dominique Mainard, Freundin Prune Lichtle nach dem Roman Vincents zweite „Leur histoire“ von Freundin Cécile Bois Dominique Mainard Baba Esther Gorintin Kamera Yves Angelo Muriels Tochter Gabrielle Lopes- Schnitt Thierry Derocles Benites Ton Pierre Gamet Muriels Sohn Louis Pottier-Arniaud Mischung Gérard Lamps Clara als Kind Clarisse Baffier Musik Christophe Claras Mutter Niki Zischka Jean-Michel Jarre Claras Vater Laurent Le Doyen Ausstattung Solange Zeitoun Claras Lehrerin Geneviève Yeuillaz Kostüm Julie Mallard Maske Sophie Benaiche Camille Gauthier Regieassistenz Vincent Trintignant Casting Gérard Moulevrier Pascale Beraud WORTE IN BLAU Produktionsltg. Frédéric Blum Anna ist ein kleines Mädchen von sechs Jahren, das sich weigert zu sprechen. Produzenten Michèle Petin Clara, ihre Mutter, wollte niemals lesen oder schreiben lernen. Einsam und Laurent Petin getrennt von der Welt betrachtet Anna ihre Mutter dabei, wie sie etwas in Co-Produktion France 3 Cinéma, ihre Taschen stopft oder wie sie etwas in den Saum ihrer Ärmel einnäht. Es Paris sind kleine Notizzettel, auf die Clara sich ihre Adresse hat schreiben lassen Produktion oder die Titel jener Bücher, die die Kleine so liebt, oder die Rezepte ihrer ARP liebsten Kuchen oder die Strophen ihrer Wiegenlieder. Denn es könnte pas- 13, rue Jean Mermoz sieren, dass sie sich für immer verlieren. Diese Notizzettel sind die einzige F-75908 Paris Wegzehrung, mit der das Kind versorgt ist, als es in die Schule für Taub- Tel.: 1-56 69 26 00 Fax: 1-45 63 83 37 stumme kommt. -

Guide to the Papers of the Capri Community Film Society

Capri Community Film Society Papers Guide to the Papers of the Capri Community Film Society Auburn University at Montgomery Archives and Special Collections © AUM Library Written By: Rickey Best & Jason Kneip Last Updated: 2/19/2008 TABLE OF CONTENTS Content Page # Collection Summary 2 Administrative Information 2 Restrictions 2-3 Index Terms 3 Agency History 3-4 1 of 64 Capri Community Film Society Papers Scope and Content 5 Arrangement 5-10 Inventory 10- Collection Summary Creator: Capri Community Film Society Title: Capri Community Film Society Papers Dates: 1983-present Quantity: 6 boxes; 6.0 cu. Ft. Identification: 92/2 Contact Information: AUM Library Archives & Special Collections P.O. Box 244023 Montgomery, AL 36124-4023 Ph: (334) 244-3213 Email: [email protected] Administrative Information Preferred Citation: Capri Community Film Society Papers, Auburn University Montgomery Library, Archives & Special Collections. Acquisition Information: The collection began with an initial transfer on September 19, 1991. A second donation occurred in February, 1995. Since then, regular donations of papers occur on a yearly basis. Processed By: Jermaine Carstarphen, Student Assistant & Rickey Best, Archivist/Special Collections Librarian (1993); Jason Kneip, Archives/Special Collections Librarian. Samantha McNeilly, Archives/Special Collections Assistant. 2 of 64 Capri Community Film Society Papers Restrictions Restrictions on access: Access to membership files is closed for 25 years from date of donation. Restrictions on usage: Researchers are responsible for addressing copyright issues on materials not in the public domain. Index Terms The material is indexed under the following headings in the Auburn University at Montgomery’s Library catalogs – online and offline. -

A Film by André Téchiné

ARP Sélection presents GOLDEN YEARS a film by André Téchiné France / 2017 / 103’ / 1:85 / 5.1 / French INTERNATIONAL PUBLICITY International Press WOLF Consultants T: +49 157 7474 9724 (in Cannes) M: +33 7 60 21 57 76 [email protected] DOWNLOAD PRESS MATERIALS at: www.wolf-con.com/download International Sales Celluloid Dreams 2 rue Turgot - 75009 Paris T +33 1 49 70 03 70 www.celluloid-dreams.com The true love story of Paul and Louise who get married on the eve of WWI. Injured, Paul deserts. Louise decides to hide him dressed as a woman. He soon becomes “Suzanne” a Parisian celebrity in the Roaring 20’s. When granted amnesty, he is challenged to live as a man again. A Dream Come True for Historians by Fabrice Virgili and Danièle Voldman While doing some scholarly work at the Paris police archives, we stumbled across the extraor- dinary story of Paul and Louise, two young people who fell in love in early twentieth-century Paris. When war was declared in July 1914, Paul was mobilized and sent to the front. What then followed was, to say the least, a baroque adventure that could not help but interest André Téchiné, who in 1976 directed the intriguing Barocco. The couple found separation difficult, and Paul could not take the fighting, horror and carnage. Wounded, he deserted and escaped back to Louise. And thus began their ‘golden’ years, escaping the military authorities who were hunting down failed patriots. Paul the deserter disguised himself as a woman and, for ten years, until a general amnesty was declared, Paul became Suzanne and lived as a flapper with Louise. -

Press Information September | October 2016 Choice of Arms The

Press Information September | October 2016 Half a century of modern French crime thrillers and Samuel Beckett and Buster Keaton 's collaboration of the century in the year of 1965; the politically aware work of documentary filmmaker Helga Reidemeister and the seemingly apolitical "hipster" cinema of the Munich Group between 1965 and 1970: these four topics will launch the 2016/17 season at the Austrian Film Museum. Furthermore, the Film Museum will once again take part in the Long Night of the Museums (October 1); a new semester of our education program School at the Cinema begins on October 13, and the upcoming publications ( Alain Bergala's book The Cinema Hypothesis and the DVD edition of Josef von Sternberg's The Salvation Hunters ) are nearing completion. Latest Film Museum restorations are presented at significant film festivals – most recently, Karpo Godina's wonderful "film-poems" (1970-72) were shown at the Cinema Ritrovato festival in Bologna – the result of a joint restoration project conducted with Slovenska kinoteka. As the past, present and future of cinema have always been intertwined in our work, we are particularly glad to announce that Michael Palm's new film Cinema Futures will have its world premiere at the Venice Film Festival on September 2 – the last of the 21 projects the Film Museum initiated on the occasion of its 50th anniversary in 2014. Choice of Arms The French Crime Thriller 1958–2009 To start off the season, the Film Museum presents Part 2 of its retrospective dedicated to French crime cinema. Around 1960, propelled by the growth spurt of the New Wave, the crime film was catapulted from its "classical" period into modernity. -

GAUMONT PRESENTS: a CENTURY of FRENCH CINEMA, on View Through April 14, Includes Fifty Programs of Films Made from 1900 to the Present

The Museum of Modern Art For Immediate Release January 1994 GAUNONT PRESENTS: A CENTURY OF FRENCH CINEMA January 28 - April 14, 1994 A retrospective tracing the history of French cinema through films produced by Gaumont, the world's oldest movie studio, opens at The Museum of Modern Art on January 28, 1994. GAUMONT PRESENTS: A CENTURY OF FRENCH CINEMA, on view through April 14, includes fifty programs of films made from 1900 to the present. All of the films are recently restored, and new 35mm prints were struck especially for the exhibition. Virtually all of the sound films feature new English subtitles as well. A selection of Gaumont newsreels [actualites) accompany the films made prior to 1942. The exhibition opens with the American premiere of Bertrand Blier's Un deux trois soleil (1993), starring Marcello Mastroianni and Anouk Grinberg, on Friday, January 28, at 7:30 p.m. A major discovery of the series is the work of Alice Guy-Blache, the film industry's first woman producer and director. She began making films as early as 1896, and in 1906 experimented with sound, using popular singers of the day. Her film Sur la Barricade (1906), about the Paris Commune, is featured in the series. Other important directors whose works are included in the exhibition are among Gaumont's earliest filmmakers: the pioneer animator and master of trick photography Emile Cohl; the surreal comic director Jean Durand; the inventive Louis Feuillade, who went on to make such classic serials as Les Vampires (1915) and Judex (1917), both of which are shown in their entirety; and Leonce Perret, an outstanding early realistic narrative filmmaker. -

Feature Films

Libraries FEATURE FILMS The Media and Reserve Library, located in the lower level of the west wing, has over 9,000 videotapes, DVDs and audiobooks covering a multitude of subjects. For more information on these titles, consult the Libraries' online catalog. 0.5mm DVD-8746 2012 DVD-4759 10 Things I Hate About You DVD-0812 21 Grams DVD-8358 1000 Eyes of Dr. Mabuse DVD-0048 21 Up South Africa DVD-3691 10th Victim DVD-5591 24 Hour Party People DVD-8359 12 DVD-1200 24 Season 1 (Discs 1-3) DVD-2780 Discs 12 and Holding DVD-5110 25th Hour DVD-2291 12 Angry Men DVD-0850 25th Hour c.2 DVD-2291 c.2 12 Monkeys DVD-8358 25th Hour c.3 DVD-2291 c.3 DVD-3375 27 Dresses DVD-8204 12 Years a Slave DVD-7691 28 Days Later DVD-4333 13 Going on 30 DVD-8704 28 Days Later c.2 DVD-4333 c.2 1776 DVD-0397 28 Days Later c.3 DVD-4333 c.3 1900 DVD-4443 28 Weeks Later c.2 DVD-4805 c.2 1984 (Hurt) DVD-6795 3 Days of the Condor DVD-8360 DVD-4640 3 Women DVD-4850 1984 (O'Brien) DVD-6971 3 Worlds of Gulliver DVD-4239 2 Autumns, 3 Summers DVD-7930 3:10 to Yuma DVD-4340 2 or 3 Things I Know About Her DVD-6091 30 Days of Night DVD-4812 20 Million Miles to Earth DVD-3608 300 DVD-9078 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea DVD-8356 DVD-6064 2001: A Space Odyssey DVD-8357 300: Rise of the Empire DVD-9092 DVD-0260 35 Shots of Rum DVD-4729 2010: The Year We Make Contact DVD-3418 36th Chamber of Shaolin DVD-9181 1/25/2018 39 Steps DVD-0337 About Last Night DVD-0928 39 Steps c.2 DVD-0337 c.2 Abraham (Bible Collection) DVD-0602 4 Films by Virgil Wildrich DVD-8361 Absence of Malice DVD-8243