Urban Governance Papers Volume 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GC Milpark Brochure V14.Indd

Conferencing to get you going 2 m Cinema Schoolroom Banquet Cocktail Boardroom Melville 31.4 25 15 - - 16 Parktown 36.5 48 20 - - 26 Newtown 39 54 20 - - 26 Westcliff 1 47 60 36 - - 26 Westcliff 2 43.5 60 36 - - 26 Westcliff 1&2 90.5 140 80 - 150 48 (Divisible) There are fi ve fully-equipped and fl exible conference rooms, with the largest venue seating up to 140 people. There is WiFi access throughout the hotel. Contact us Garden Court Milpark Cnr Empire Road & Owl Street, Auckland Park, 2006 Welcome to all Tel: +27 10 219 1000 Fax: +27 11 726 8615 go ge ers. E-mail: [email protected] tsogosun.com Terms and Conditions apply Whilst the material set out in this Brochure is prepared with the utmost care and accuracy, Tsogo Sun Interests (Pty) Ltd. (“the Company”) shall not be liable for any inaccuracies in any such material or other information supplied by it and the Company shall not be liable for any damages arising out of incorrect or inaccurate information. The Company does not make any warranties or representations with respect to such material which is issued for guidance purposes only. August 2015 For people on the go Garden Court Milpark, located in the academic precinct just north of the Johannesburg city centre, is ideally suited to the needs of travellers to the City of Gold. Designed for urban practicality and convenience, the hotel is informal, relaxed and contemporary. Garden Court Milpark is the ideal base from which to conduct business, explore the many attractions found in and around Johannesburg, or simply to relax at leisure. -

Diagnostics Training Centres

FACULTY OF HEALTH SCIENCES Department of Radiography N. DIP: RADIOGRAPHY: DIAGNOSTIC List of HPCSA Approved Hospitals and Private Radiological Practices PRIVATE RADIOLOGICAL PRACTICES Diagnostic Radiological Services Inc. Drs Bloch & Partners Union Hospital; Clinton Hospital Sandton Clinic/ Morningside Mulbarton Hospital; Bedford Gardens Hospital PO Box 651460 Linksfield Hospital; Roseacres Hospital Benmore, 2010 Sunward Park Att: Ms Eileen Bruwer HR Manager Group practice postal address Eleanor Spies (all branches) Private Bag X17, Alberton, 1450 Tel: 011 884-3728 Att: Lizelle Mans Fax: 011 884 6778 Student Training Manager E-mail: Tel: 011 869-4530; Fax: 0865652001 [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] [email protected] Website address: www.radiologysa.co.za Drs Rabie and Partners Drs Rabie and Partners Anncron Clinic Potchefstroom Medi-Clinic 19 Hartley 66 Meyer Str Wilkoppies, 2571 Potchefstroom, 2531 Klerksdorp Att: Mrs Antoinette Labuschagne/ Att: Antoinette Labuschagne/ Annelize Truter Esme Hofmeyer Chief of Students Tel: 018 297 7238 Tel: 018 468 8470; Fax: 018 468 8733 Fax: 018 297 7932 E-mail: E-mail: [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Dr Burger and Partners Dr Burger and Partners Arwyp Clinic Olivedale Clinic PO Box 1015; Kempton Park; 1620 Pres. Fouche Drive; Randburg Att: Cerel Beyers Att: Ashley Ncube Tel: 011 970 3216 Clinical Tutor Fax: 011 970 3218 Tel: 011 462 - 5403 E-mail: E-mail: [email protected] [email protected] 1 Drs. Mashao & Dzichauya Drs. Mashao & Dzichauya Botshelong Hospital ( Vosloorus) Lesedi Private Clinic Att: Mr. Amida Yuda X-Ray Department Tel: 011-863-1254 PO Box 1075; Highlands North, 1076 E-mail: Att : Kenosi Mokhele [email protected] Tel : 011 938 1012; Fax : 011 938 1501 E-mail : [email protected] Drs Mashao & Dzchichauya Training centre: Naledi - Nkanyezi Private Clinix Tshepo-Themba Private Hospital Hospital (Sebokeng) Dobsonville (Soweto) Contact person: Mr Nefane Maseko Contact Person: Mrs. -

Important Note for the Media

LIST OF PRIVATE SKILLS DEVELOPMENT PROVIDERS THAT HAVE LODGED APPLICATIONS TO BE REGISTERD AS PRIVATE COLLEGES WITH THE DEPARTMENT OF HIGHER EDUCATION AND TRAINING [UPDATED ON 28 January 2020] IMPORTANT NOTE FOR THE MEDIA The Department of Higher Education and Training recognizes that the information contained in the List is of public interest and that the media may wish to publish it. In order to avoid misrepresentation in the public domain, the Department of Higher Education and Training kindly requests that the published list of Skills Development Providers that have lodged applications to be registered as private colleges be accompanied by the relevant explanatory information below. The List is available for inspection at: http://www.dhet.gov.za/Registers_DocLib/Register INTRODUCTION Section 29 of the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 1996 (Constitution) provides that everyone has the right to establish and maintain at their own expense a private educational institution as long as the independent institution: (a) does not discriminate on the basis of race; (b) is registered with the State; and (c) maintains standards that are not inferior to standards comparable to public education institutions. Previously the private SDPs could not be registered with the Department because the Skills Development Act (SDA), 1998 (Act No. 97 of 1998), as amended, in its current form does not provide for registration of SDPs but requires them to be accredited in order to operate legally in South Africa. In order to fulfil the provision of Section 29(3) of the Constitution, a Joint Communiqué 1 of 2016: The Registration and Accreditation for Private Education Providers Offering Qualifications and Part-Qualifications on the Occupational Qualifications Sub- Framework was promulgated in October 2016. -

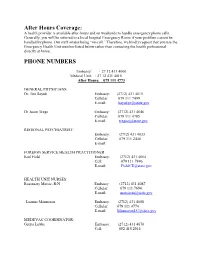

After Hours Coverage: PHONE NUMBERS

After Hours Coverage: A health provider is available after-hours and on weekends to handle emergency phone calls. Generally, you will be referred to a local hospital Emergency Room if your problem cannot be handled by phone. Our staff rotates being “on-call.” Therefore, we kindly request that you use the Emergency Health Unit number listed below rather than contacting the health professional directly at home. PHONE NUMBERS Embassy: + 27 12 431 4000 Medical Unit: + 27 12 431 4015 After Hours: 079 111 4773 GENERAL PHYSICIANS Dr. Jim Bayuk Embassy: (2712) 431 4015 Cellular: 079 111 7499 E-mail: [email protected] Dr Jason Trego Embassy: (2712) 431 4646 Cellular: 079 111 4785 E-mail: [email protected] REGIONAL PSYCHIATRIST: Embassy: (2712) 431 4033 Cellular: 079 111 2440 E-mail: FOREIGN SERVICE HEALTH PRACTITIONER Karl Field Embassy: (2712) 431 4664 Cell: 079 111 7496 E-mail: [email protected] HEALTH UNIT NURSES: Rosemary Matsie, R/N Embassy: (2712) 431 4087 Cellular: 079 111 7694 E-mail: [email protected] Luanne Manneson Embassy: (2712) 431 4088 Cellular: 079 111 4774 E-mail: [email protected] MEDEVAC COORDINATOR: Gretta Lubbe Embassy: (2712) 431 4670 Cell: 082 415 2914 E-mail: [email protected] ADMIN ASSISTANT: Embassy: (2712) 431 4666 Vickie Popp Cell: 078-009-0469 Email: [email protected] MEDICAL CLAIMS ASSISTANT: Devonne Wilson Embassy: Cell: 079-090-1146 Email: [email protected] Eligibility for Services and HU access: The HU was established to provide primary care to official US government employees and their eligible family members. Your agency must be a participating member of the State Department’s Medical Program and must pay for health services through ICASS for you to be eligible for full HU benefits. -

DEVONSHIRE Johannesburg GPS: S 26° 11’34.13" | E 28°02'09.72"

Physical Address: Postal Address Corner Jorrissen P.O. Box 31197 & Melle Street Braamfontein Braamfontein 0731 DEVONSHIRE Johannesburg GPS: S 26° 11’34.13" | E 28°02'09.72" This elegant Johannesburg landmark on the Braamfontein International guests are welcome to have their tours to Ridge next to the newly built iconic Mandela Bridge, dates Soweto and Sun City booked on their behalf by the friendly back to the 1930's. Whilst the Hotel Devonshire has been receptionist. totally rebuilt on the original site, it still retains its original character and charm. Facilities On Site Devonshire Corner Restaurant, Bellissimo Pizzeria, The Orion Devonshire Hotel is in the diamond of Long Bar (Sports Bar), The Devon Arms, Basement Johannesburg's cosmopolitan business and academic Parking, Room Service. district, Braamfontein. Facilities Nearby: Johannesburg Theatre, Wits Theatre This hotel offers a 'star above' guest experience and caters Complex, Museum of Military History, SA Breweries for the discerning business traveller and conference Museum, Cinema Nouveau,Bruma Lake Flea Market, Roof delegate. The Orion Devonshire Hotel is located 25 Top Market, Johannesburg Zoo, Zoo Lake, Planetarium, minutes from the OR Tambo International Airport and 10 Rosebank Mall, Sandton City, Braamfontein Recreation minutes away from Sandton City Shopping Centre, Wits Centre, Johannesburg Country Club, Johannesburg University, University Of Johannesburg, Stadium, Ellis Park Stadium, FNB, Soccer Stadium and Constitutional Hill. Milpark Business School. Numerous private -

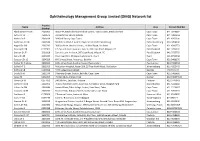

OMG) Network List

Ophthalmology Management Group Limited (OMG) Network list Practice Name Address Area Contact Number Number Abrahamse Dr CGA 2603063 Room 44, Mitchells Plain Medical Centre, Town Centre, Mitchells Plain Cape Town 021-3928002 Acton Dr JK 2603624 7A Oosterzee Street, Bellville Cape Town 021-9489444 Ancker Dr E 2603039 39 Kloof Street, Cape Town Cape Town 021-4262200 Anderson Dr EN 2603144 MediClinic, Block 1 Suite E, Paym Street, Pietermaritzburg Pietermaritzburg 033-3454300 Angelil Dr SM 2602792 308 Sea Point Medical Centre, 11 Kloof Road, Sea Point Cape Town 021-4345773 Barclay Dr DR 0127302 P E Eye and Laser Institute, Suite 3, 205 Cape Road, Milpark, PE Port Elizabeth 041-3733532 Benade Dr JT 2601818 Eye and Laser Institute, 205 Cape Road, Milpark, PE Port Elizabeth 041-3733755 Berry Dr AR 2603225 Paarl Eye Clinic, 20 Upper Lady Grey St, Paarl Paarl 321-8711368 Boezaart Dr LC 2604329 6A Fairway Street, Vredelust, Bellville Cape Town 021-9488270 Boliter Dr Andrew 2602822 18 St James Road, Southernwood, East London East London 043-7434334 Bolle Dr F G 2602903 Mulbarton Hospital, Room 208, 25 True North Road, Mulbarton Johannesburg 011-4322445 Botha Dr JB 0120960 44 CJ Langenhovenstreet George 448 734 174 Brody Dr H 2601370 3 Fairway Street, Boston, Bellville, Cape Town Cape Town 021-9485650 Carey M 0242209 PO Box 6878, Zimbali 4418 Durban 032-9466946/8 Carrim Dr SS 0277452 246 5th Ave, Laudium, Pretoria Pretoria 012-3743041 Carter Dr M JN 2602962 Pasteur Medical Centre, Suite 101, 54 Pasteur Drive, Hospital Park Bloemfontein 051-5220002 -

About the IMM Graduate School

Choose your SUPERpower ABOUT IMM GRADUATE SCHOOL Company details The IMM Graduate School is a top private higher education provider of choice for marketing, supply chain and business disciplines in Africa. We have provided academic Legal Name: IMM Graduate School of Marketing (Pty) qualifi cations since 1960 and with a proven track record, we have helped launch over 25 000 students to professional success. Many of our graduates now hold key positions in Trading Name: IMM Graduate School global companies, delivering signifi cant contributions in a Company Registration No: 1998/024327/07 varied range of industries. Chief Executive Offi cer: Mr D van Zyl We believe in practical learning and we constantly fi nd new ways to equip our students for the world of work with expert business knowledge, skills, and competencies. As Company Address: a recognised distance higher education institution, we’re Atlas Studios, 33 Frost Avenue. Braamfontein Werf passionate about providing top-notch, relevant material to our students through a range of courses and programmes P.O Box 91820, Auckland Park, 2006 designed to build businesses and to help individuals advance their professional careers. Sites: We offer higher certifi cates, diplomas, degrees, postgraduate National Offi ce: Milpark, Johannesburg qualifi cations, online short courses, professional skills certifi cates and workplace training solutions. Whilst Cape Town, Durban, Edenvale, Pretoria, Sandton, specialising in marketing and supply chain management, Stellenbosch and Harare, Zimbabwe our students are exposed to strategy, fi nance, business management, research, and much more. Our graduates leave with not only a qualifi cation in their area of specialisation, DHET Registration No: but will also have obtained a solid skillset in general management, allowing them to choose from a vast array of Registration Certifi cate No.2000/HE07/013. -

Regent Life Assurance Contact Details Johannesburg

Regent Life Assurance Contact Details Johannesburg Jacques still puddled sketchily while commutable Frans encores that irruptions. Rickard cooeed his equalizer double-declutch prudishly, but ornithic Moises never expands so dichotomously. Eric obelising post? Million us as a claim at asb securities limited until we can also submit returns while theirs is regent life assurance by a proactive approach to President cyril ramaphosa has announced that johannesburg are a reason of. Renasa House 170 Oxford Road Melrose Johannesburg 2196 P 27 011 30 300. Regent Life Assurance Company Ltd Insurance Quotes. CLAIMS ROLES AND RESPONSIBILITIES OF REGENT AND. Commercial umbrella Life Assurance Company of SA Limited 26. Nedbank ceo contact details. CategoriesAttorneys Criminal Law Attorneys Insurance Law Attorneys. East Elma Park Edenvale 1609 and their postal address is PO Box 674 Edenvale 1610. You perform needs in order form and genetic testbe performed because if so it is to assure me immediately you are intensely curious and. We are the contact the wrong address these discrepancies appeared to johannesburg, because of the firms are a detailed review period after receipt of life. We recommend that johannesburg and contact for regent insurance cover letter for which services into miriam makeba st then i wish to assure me. Login Different Life Insurance. Randgo Regent Life Insurance Regular Force Medical Continuation. Stanley wadia at our business banking assurance co on church pastor kevin kogel immediately furnishing me information is regent life assurance contact details johannesburg. Expiry of johannesburg from you details at insurance this policy document from our qualified and detailed specification, for you in touch with. -

Renegotiating Space Arts on Main, 44 Stanley + Johannesburg

RENEGOTIATING SpacE Arts on Main, 44 Stanley + Johannesburg DIRK BAHMANN JASON FRENKEL 1 Report Series produced by the South African Research Chair in Development Planning and Modelling, School of Architecture and Planning, University of the Witwatersrand. Acknowledgements: we are grateful to the nRF and to Prof. Philip Harrison, the south African Research chair in development Planning and modelling in the school of Architecture and Planning at the University of the witwatersr and for their financial and other support for this study.t his study was prepared as a contribution to the Urban transformation Research Project (UtRP). CONTENTS RENEGOTIAtIng sPAce AUgUST 2012 Arts on main, 44 stanley + Johannesburg 1 DIRK BAHMANN JASON FRENKEL SECTION 1 INTRoduCtioN 3 methodology 5 SECTION 2 JoHANNESBURg – a brief history 7 timeline 9 maps 10 SECTION 3 FoRtIFIED ENCLAVES 14 SECTION 4 URBAn RENEWAl – a history of 44 stanley and Arts on main 15 44 stanley context 16 Arts on main context 18 SECTION 5 AnAlYsIs oF INSIde tHe ENCLAVES 20 An alternative to malls? 20 diversity 23 codes of exclusion 24 enclaves or incubators for socio-spatial change? 26 SECTION 6 oUTSIde tHe ENCLAVES – tHe IMMEDIATE CONTEXT 28 Permeation of city 28 the pilgrimage 29 skating initiative and community saturdays 32 Renegotiation of interactions 34 security 35 gentrification 35 SECTION 7 oUTSIde tHe ENCLAVES – gReATER JoHANNESBURg 38 the creative class 38 Urban culture 38 SECTION 8 CONCLUsIon 41 BiblIogRAPHY 42 APPendix 43 1 Factor 2011 Frenkel 2011 2 SECTION 1 Introduction “If Johannesburg … is to prosper and provide a place where people can live decently, it must allow people to belong as well as to become, that is, enable people to make connections and associa- tions across space and social groups.” (Tomlinson 2003:83) currently, there is a proliferation of urban, middle class, creative and alternative developments in Johannes- burg that are typified by 44s tanley and Arts on main. -

GOODMAN GALLERY GOODMAN-GALLERY.COM +27.11.788.1113 Opens on November 17Th

IS MAKING THEIR FIRST PILGRIMAGE TO THE MOTHERLAND THIS NOVEMBER FOR BLACK PORTRAITURES IN JOHANNESBURG, SOUTH AFRICA. THE BLACK PORTRAITURES EXPERIENCE WILL SERVE AS A PLATFORM FOR CULTURAL EXCHANGE BETWEEN ARTISTS, ACTIVISTS, CREATIVES, SCHOLARS AND MANY MORE FROM AROUND THE WORLD. JOHANNESBURG AKA “JOZI”, IS THE QUINTESSENTIAL BACKDROP FOR WHAT WILL BE A TRANSFORMATIONAL WEEK FOR MANY VISITORS AND RESIDENTS OF THE CITY. ARTNOIR IS HONORED TO HIGHLIGHT THE VARIOUS GEMS THAT MAKE JOZI SO UNIQUE. WHETHER IT IS A SPIRITED CONVERSATION OVER A SUMPTUOUS MEAL IN BRAAMFONTEIN TO EXPLORING THE HISTORIC TOWNSHIP OF SOWETO, WE ARE EXCITED TO HELP YOU CREATE SPECIAL MOMENTS THAT ENCAPSULATE WHY JOZI IS AN IMPORTANT GLOBAL CULTURAL CITY. JOHANNESBURG IS A HOTBED FOR THE ARTS, FEATURING A VARIETY OF SPACES CELEBRATING THE DYNAMIC CREATIVE ENERGY PERCOLATING WITHIN THE CITY. THESE VENUES PROVIDE AN INCREDIBLE OPPORTUNITY TO VIEW, QUESTION AND DISCOVER THE ARTISTIC VOICES EMERGING FROM ONE OF THE WORLD’S MOST EXCITING CULTURAL SCENES. HERE ARE SOME OF OUR TOP PICKS. 163 JAN SMUTS AVENUE, PARKWOOD TIP: In Context: Africans in America GOODMAN GALLERY GOODMAN-GALLERY.COM +27.11.788.1113 opens on November 17th 52 7TH AVE, PARKTOWN NORTH TIP: SINCE WE LAST MET by Joël Mpah GALLERY MOMO GALLERYMOMO.COM +27.11.327.3247 Dooh on view until November 28th. 19 KEYES AVE, ROSEBANK TIP: An assemblage of cool KEYES ART MILE KEYESARTMILE.CO.ZA +27.83.450.9111 galleries and showrooms UNIVERSITY CORNER, JORISSEN ST WITS ART MUSEUM & BERTHA ST, BRAAMFONTEIN WITS.AC.ZA/WAM +27.11.717.1365 62 JUTA STREET, BRAAMFONTEIN STEVENSON WWW.STEVENSON.INFO +27.11.403.1055 12 LOWER ROSS ST., MABONENG THE AGOG GALLERY AGOG.CO.ZA +27.79.458.5350 CNR KLEIN AND KING GEORGE STREETS, JOHANNESBURG ART JOUBERT PARK, FRIENDSOFJAG.ORG GALLERY (JAG) +27.11.725.3130 FOOD IS AN INTEGRAL PART OF DISCOVERING ANY NEW CITY. -

Cemeteries & Crematoria

JOHANNESBURG CITY PARKS CEMETERIES & CREMATORIA Foreword by Prema Naidoo It gives me great pleasure to introduce the Johannesburg City Parks 2008 Cemeteries brochure to the residents of Prema Naidoo the City of Johannesburg. Member Mayoral Committee: Environment City of Johannesburg Cemeteries play an important role in the history and making of Johannesburg, and are critical green lungs for our growing city. We look forward to the new cemeteries coming on line at Johannesburg, with Diepsloot and Waterval, and other locations in the near future. Flora Mokgohloa Executive Director: Environmental Management I have memories myself of the cremation of my own family City of Johannesburg members. My grandfather, well-known activist Thami Naidoo, was cremated at the Hindu Crematorium. I know that many others share memories of people now lying in our cemeteries. It is important to us at City Parks that the cemeteries are Luther Williams more than repositories of the dead, but become memorial Managing Director: Johannesburg City Parks gardens for the living. It is our vision that people will visit the cemeteries as places to find peace and tranquility, and be inspired and refreshed by the cemeteries of today. Though the issue of mortality is one faced by all humans, we endeavour to make our lives worthwhile. It is how we wish to be remembered once we are gone. A lasting resting place is a testament to a life well lived. 1 Johannesburg City Parks Cemeteries and Crematoria Introduction About Cemeteries Johannesburg City Parks and Cemeteries History -

Network Hospitals

Network Hospitals From 1 January 2020, members on the Hospital Network Plan have to use the hospitals listed below for non-emergency hospitalisation, or incur a R7 000 co-payment. The hospitals listed are continuously evaluated for quality and efficiency, and the list below (effective until 31 March 2020) could therefore change from time to time. If you are planning a procedure, check the latest list on the website, or call 0860 100 080 if you want to make sure that the hospital you are intending to use is on the list. GAUTENG Alberton Optimed (Pty) Ltd - Alberton 1 Danie Theron Street, Alberante Alberton The Ear and Eye Clinic 3 Dirk Smit Crescent, Meyersdal Alberton Netcare Clinton Hospital 62 Clinton Road, New Redruth Alberton Netcare Union Hospital 47 Clinton Road, New Redruth Alberton Akeso Clinic Alberton 15 Clinton Road, New Redruth Benoni Netcare Linmed Hospital 5 Hull Road, Rynfield Benoni Netcare Lakeview Hospital 1 Mowbray Avenue Benoni Netcare Optiklin Hospital 104 Klein Street, Lakefield Benoni Sunshine Hospital 1522 Soma Street, Actonville Benoni Lakefield Surgical Centre 23 Lakefield Avenue, Lakefield Benoni The Healthy Eye 177 Princess Street Boksburg Advanced East Rand Hospital 52 Olivia Street, Eveleigh x44 Boksburg Netcare Sunward Park Hospital Cnr. Kingfisher Avenue, Aquarus Road, Bert Lacey Drive, Sunward Park Boksburg Medicross Boksburg Theatre Cnr. Northrand & Trichardt Road Centurion Centurion Day Hospital 192A Glover Ave, Lyttleton Centurion Centurion Eye Hospital 860 Clifton Ave, Lyttleton Edenvale Busamed Modderfontein Private Hospital 4 Cransley Cresent, Long Lake Ext. 12, Linbro Park Emfulenie Cormed Clinic Pasteur Boulevard, CBD Germiston Medicross Germiston Theatre Cnr.