U.S. POSTAL SERVICE, Respondent

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mutual Respect Is a Two Way Street!

MOUND 2010 Award Winning Publication CITY CARRIER St. Louis, Missouri Official Publication of Branch 343 Chartered 1892 Volume 62, No. 8 August 2011 MUTUAL RESPECT IS A MOUND MOUND city TWO WcityAY ST R EET ! PRESIDENTcarrier’S ARTICLE … BY BILL LISTER carrier ver the past year there have been severalOfficial incidents Publication where of employeesBranch 343 have been accused by manage- Official Publication of Branch 343 ment of talking or acting in a threateningSt. Louis, manner. MO Each of these employees were placed off the clock St. Louis, MO with management claiming an emergencyChartered situation 1892 from our contract, as well as a violation of the Joint Chartered 1892 OStatement on Violence in the Workplace. The Joint Statement was the eventual result of management’s foray into promoting managers who lacked the skills to talk to people in a professional and respectful manner, back in the mid 1980s. Many of these under-qualified yet upwardly mobile employees were incapable of managing, so they abused their power by constantly intimidating, coercing and threatening craft employees, to make the numbers. After two horribly regrettable shootings in two distant offices, the national parties of the USPS and all the postal unions signed the Joint Statement in a combined effort to stop the abuse. At that time, it seemed as though the service had finally realized that pushing its folks from the top levels to make the numbers by using any means possible, was the primary cause of all the problems on the workroom floor. Add someone who manages by intimidation and a craft employee with personal issues, and you have a recipe for disaster. -

Brown in Bologna! Programhandbook! Fall 2017!

Brown in Bologna! Program Handbook! Fall 2017! Brown University! Office of International Programs! Table of Contents Program Contacts ………………………………………………………………… 2 Welcome ………………………………………………………………………….. 3 – 4 Academic Information …………………………….………………………….…… 5 – 8 Health and Safety …………………………….………………………….………… 10 – 11 Money Matters …………………………….…………………………………….… 12 Arriving and Surviving …………………………….………………………….…….. 13 What to Bring …………………………….………………………….…………..… 14 – 15 Life in Bologna …………………………….………………………….…………..…16 – 18 A Final Note …………………………….………………………….…………..……19 1 Contacts Brown University in Bologna Via Belmeloro 7! 40126 Bologna!, Italy! Tel: +39 051 2960906 Fax: +39 051 6486678 When calling Italy from the U.S., remember the time difference. Italy is six hours ahead of U.S. EST. When it is l0 a.m. in Providence, it is 4 p.m. in Bologna. Program Staff Anna Maria Digirolamo Resident Director Email: [email protected] Cell Phone: +39 349 7509761 Stephen Marth (through August 31, 2017) Assistant Director Email: [email protected] Cell Phone: +39 344 0449628 Chiara Rani (as of September 1, 2017) Assistant Director Email: [email protected] Cell Phone: +39 349 8552313 Prof. Suzanne Stewart-Steinberg Brown in Italy Faculty Director 2017-18 Email: [email protected] Bologna Office Hours 8 a.m. – 6 p.m. during the first week; 8:30 a.m. – 4:30 p.m., M-Th!; 8:30 a.m. – 2 pm. Fridays Brown University Office of International Programs (OIP) Box 1973 Providence, RI 02912 Tel.: 401-863-3555! Fax: 401-863-3311 E-mail: [email protected] OIP Office Hours 8:30 a.m. – 5 p.m., M-F September – May 8 a.m. – 4 p.m., M-F June – August If you have an emergency outside of normal business hours at Brown, please call Brown University Public Safety at (401) 863-3322. -

Whistl International Pre-Sorted Customer Guide/November 2020 V1.1

International Pre-Sorted Customer Guide v1.1 Table of Contents 1.0 Overview ......................................................................................................................................................4 1.1 Who it suits .....................................................................................................................................................4 1.2 Minimum Spend ..............................................................................................................................................4 1.3 Included Services ...........................................................................................................................................4 1.4 Collections ......................................................................................................................................................4 1.5 Presentation ...................................................................................................................................................4 1.6 Force Majeure Events.....................................................................................................................................5 2.0 General Description ...............................................................................................................................6 2.1 Service Aims†..................................................................................................................................................6 2.2 Addressing Requirements -

Handbook PO-502 June 2017 Transmittal Letter

Mail TransportTransmittal Equipment Letter Handbook PO-502 June 2017 Transmittal Letter A. Introduction. This handbook is a complete revision of the September 1992 edition of Handbook PO-502, Container Methods. B. Explanation. This handbook provides information about the following: 1. Postal Service Mail Transport Equipment (MTE) policies and procedures. 2. MTE and all mail transport containers. 3. Use of mail transport containers. 4. Mail Transport Equipment Service Centers (MTESCs). C. Availability. This handbook is available for Postal Service employees on the Postal Service PolicyNet Web site at http://blue.usps.gov — in the left-hand column under “Essential Links,” click on PolicyNet, and then in the tabs across the top, click on HBKs. A link to this handbook is also available from the Network Operations Management Web site at http://blue.usps.gov/network-operations. D. Comments and Questions. Submit any comments or questions regarding the content of this handbook to the following address: MANAGER MAIL TRANSPORT EQUIPMENT UNITED STATES POSTAL SERVICE 475 L’ENFANT PLZ SW RM 7142 WASHINGTON DC 20260-7132 E. Effective Date. This is effective June 2017. All previous editions are rescinded and obsolete. Robert Cintron Vice President Network Operations The following trademarks appear in the handbook and are among the many trademarks owned by the United States Postal Service®: CON-CON®, Express Mail®, First-Class Mail®, First-Class Mail International®, Post Office™, Postal Service™, Priority Mail®, Priority Mail Express®, Priority Mail Express International®, Priority Mail International®, Registered Mail™, U.S. Postal Service®, and USPS®. This is not a comprehensive list of all Postal Service™ trademarks. -

Bologna Handbook 16-17

Bologna PROGRAM HANDBOOK Brown in Italy 2016-17 Welcome to what surely will be the most exciting time so far in your life as a student. It will be a year or semester of both enjoyment and frustration, but the great times in this adventure, we can assure you, will be far more numerous than the minor frustrations you are likely to encounter. This handbook should provide useful information that will help you to prepare for the experience and to relieve anxiety about what to expect. Plan to use it in conjunction with orientation materials provided during the pre-departure orientation and on-site in Bologna. This handbook is intended both for you, the student participant, and for your parents, because we feel that both those who go away and those who stay at home should share information about the international study experience. We urge both parents and students to take the time to read the handbook from cover to cover well before departure in order to be fully informed of its contents. If you do this, then at least you will know what questions you still don’t have answers for, and you will know whom to contact to find out. It is the nature of a guide like this to advise in strong language about “do’s and don’ts”. Please pay serious attention to these remarks, which are intended for your benefit. If you have any questions or concerns about anything now or while you’re away, please contact the OIP or the Brown in Bologna office at the numbers/e-mail below. -

Front Cover 2 Postal Bulletin 22310 (5-5-11)

Front Cover 2 postal bulletin 22310 (5-5-11) Contents COVER STORY PULL-OUT INFORMATION National Dog Bite Prevention Week, May 15–21, 2011. 3 Fraud POLICIES, PROCEDURES, AND Withholding of Mail Orders . 27 FORMS UPDATES Invalid Express Mail Corporate Account Numbers . 28 Missing, Lost, or Stolen U.S. Money Order Forms . 31 Manuals Missing, Lost, or Stolen Canadian Money Order Forms . 36 DMM Revision: Market Dominant Negotiated Verifying U.S. Postal Service Money Orders . 38 Service Agreement for First-Class Mail and Counterfeit Canadian Money Order Forms . 38 Standard Mail . 15 Toll-Free Number Available to Verify Canadian IMM Revision: Mail Preparation Revisions for Money Orders . 38 International Priority Airmail and International Surface Air Lift Service . 17 Other Information Publications Overseas Military/Diplomatic Mail . 39 Publication 431 Revision: Changes to Post Office Food Drive Poster . 45 Box Service and Caller Service Fee Groups. 19 Displaying the U.S. Flag and the POW-MIA Flag . 46 Publication 521, EAP Wallet Card, Has Been Revised . 20 ORGANIZATION INFORMATION Postal Bulletin Index Delivery Annual Index. PB 22302 (1-13-11) Mailbox Improvement Week, May 16–22 . 21 Human Resources RIF Competitive Areas for the Postal Service . 58 Intelligent Mail and Address Quality Indianapolis 500 Stamp Post Office Changes . 59 Mailing and Shipping Services Mail Alert . 60 Retail Stamps by Mail — Brochure Ordering Information . 61 Stamps/Philately USPS National Emergency Hotline Pictorial Postmarks Announcement . 63 Is your facility operating? Call 888-363-7462 How to Order the First Day of Issue Digital Color or Traditional Postmarks . 68 Supply Management Voyager eFleet Card Reconciliation Report and Training . -

Publication 220 Exhibits

August 2013 Transmittal Letter Dear Member of Congress: The United States Postal Service® understands that mail is a critical tool that helps keep you in touch with your constituents. We created our Discount “Postal Customer” Mailings: A Guide for the House of Representatives with your needs in mind. It contains important information to assist your staff and mail service provider to prepare “Postal Customer” mailings. The Guide contains detailed mail preparation and entry requirements. I hope the Guide will prove to be a valuable tool to assist you in preparing trouble-free saturation mailings. An electronic version has been provided to the HouseNet website and the House Franking Commission for posting on their intranet sites. If you need additional copies — either hard copy or electronic — please let us know. Along with assisting you and your office on Postal Service™-related legislative and public policy issues — including constituent case work — your Postal Service Government Relations representative is available to help you with your “Postal Customer” mailing or other mass mailings. Sincerely, Sheila T. Meyers Manager, Government Liaison Contents 1 Introduction. 1 2 Definitions . 3 3 Basics . 5 3-1 Minimum Requirements for All Mail. 5 3-2 Dimensions for Letter-Size Mail and Flat-Size Mail. 5 3-2.1 Letter-Size Mail . 5 3-2.2 Flat-Size Mail (Enhanced Carrier Route Saturation Mailings) . 5 3-3 Mailpiece Design . 6 3-3.1 Size . 6 3-3.2 Address Format . 6 3-3.3 Price Markings . 6 3-3.4 Use of In-Home Dates . 6 4 Indicias . 7 4-1 Franked Mail . -

King's Residence Only in Name

XEW-YORK DAILY TRIBUXE. SUNDAY! JANUARY 12, 1908. " sj f^B^^^^^^ > •eiP' >j f Worn Out in TenYear«=|: j| Inventor* Are Invited |i jTo £bnd In Improvements A?^*^**^ .^a^^, J sS^^ _^^^n____^->> \ • IFrom Th* —.bun* Bureau ) Washington. Jan. 11. "The Life and Advent- bbm of a Hail Bag by Uncle Sam," would be a. good title for a book much more interesting than many that find their way into print. No on» but Uncle Sam could do justice to the nar- rative, for no one but that dear, übiquitous old relative of ours could follow one of the busy pouches as it whirls across the continent, skims eve- the ocean or flies through space to bear its precious load of messages to the army of men, women and children anxiously awaiting its ne. Briefly, and to begin at the beginning, the par- ents of the young mail bag are Cotton and Leather. There is a—little iron and a little brass In its composition a strain -of strength you might say and it* birthplace is Lyons, X Y. That Is. ail the common pouches are born at Lyons. William Taylor, the man who has the government contract, might properly be called the rnai! bag's godfather. The registry- pouches hail from Trenton. N. J.. and at that place F. Coit Johnson stands sponsor for their careers. The cotton duck of which the bags are made comes from a mill in North Carolina, and It is woven so tightly as to be practically waterproof. In the weave there are thirteen stripes of blue. -

Procedures for Handling Registered Postal Bank Remittance Mail Handbook DM-902 April 2010 Transmittal Letter A

Procedures for Handling Registered Postal Bank Remittance Mail Handbook DM-902 April 2010 Transmittal Letter A. Introduction. Handbook DM-902, Procedures for Handling Registered Postal Bank Remittance Mail, has been developed to constitute the official procedures and requirements for handling and processing Registered Postal Bank Remittance Mail. These policies and procedures have been developed in accordance with the United States Postal Inspection Service’s® national security review of the Postal Service’s Registered Mail System. This Next Generation Registered Mail System is in alignment with the strategic goals outlined in the Postal Service Strategic Transformation Plan for improving security processes, streamlining operations, generating revenue, reducing cost, and achieving results with a customer-focused performance-based culture. The governing regulations for the domestic Registered Mail system are contained in the Mailing Standards of the United States Postal Service, Domestic Mail Manual (DMM®) 503.2.0. These instructions are consistent with the procedures provided in the Handbook DM- 901, Registered Mail, the Administrative Support Manual, and Handbook F-101, Field Accounting Procedures. B. Availability. Handbook DM-902 is available via the Postal Service PolicyNet Web site: Go to http://blue.usps.gov. In the left-hand column,under “Essential Links,” click PolicyNet. Click HBKs. (The direct URL for the Postal Service PolicyNet Web site is http://blue.usps.gov/cpim.) C. Comments. 1. Content. Refer all questions and suggestions about the content of this document to: PROCESSING OPERATIONS US POSTAL SERVICE 475 L’ENFANT PLAZ SW WASHINGTON, DC 20260-6808 2. Clarity. Refer all questions about the organization of this document and any editorial suggestions to: INFORMATION POLICIES AND PROCEDURES US POSTAL SERVICE 475 L’ENFANT PLAZ SW WASHINGTON, DC 20260-6808 Jordan M. -

Postal Bulletin 22089 (11-14-02)

SEE PAGE 8 FOR INFORMATION ON IMPROVING SECURITY EFFORTS PUBLISHED SINCE MARCH 4, 1880 PB 22089, November 14, 2002 R 2 POSTAL BULLETIN 22089 (11-14-02) CONTENTS The Postal Bulletin is also available on the World Wide Employes (continued) Web at http://www.usps.com/cpim/ftp/bulletin/pb.htm for 2003 Social Security and Medicare Tax Withholding. 71 customers and at http://blue.usps.gov for employees. Form W-5 Renewal. 71 Penalty Overtime Exclusion. 71 Christmas Pay Procedures for Rural Carriers. 72 USPSNEWS@WORK . 3 2002 to 2003 Leave Year — Annual Leave Carryover. 89 Notice to all Employees: Thrift Savings Plan Administrative Services Fact Sheet. 91 Directives and Forms Update. 5 Door, Keys, and LLVs — Postal Service Security Efforts Finance Need Improvement. 8 Districts Migrating From SFAS to SAFR: SAFR Unit Maintenance Application. 93 Customer Relations Notice Available Online: Notice 25, Postal Accounting Mail Alert. 11 Period Planning Schedule, Postal Fiscal Year 2003 . 93 Publicity Kit: Holiday 2002 Publicity Kit for Annual Vending Machine Income Report Due Soon. 94 Postmasters. 11 International Mail Domestic Mail ICM Updates: International Customized Mail. 97 Correction/DMM Transformation: Ordering Information for DMM 100. 30 Philately DMM Revision: Simplified Address Format for Letter-Size Pictorial Cancellations Announcement. 99 and Flat-Size Standard Mail and Periodicals. 30 Special Cancellation Die Hubs. 101 DMM Revision: Metal Strapping Materials on Pallets. 32 DMM Revision: Realignment of Buffalo and Pittsburgh Summaries of Recent USPS News Releases . 102 Postal Service Facilities for Deposit of DBMC Rate Post Offices Standard Mail and Package Services Machinable Reminder: Retrieval of Plastic Label Holders. -

Show Guide 2008

ROT& MELBOUU SUO September 18-28 ow.com.au. w.royalsh wwOfficial Show Guide 2008 .: ..-..",.. Grand Thomas Cook & Wrangler i. :1 Pavilion Show Sale %.,;:. ''. THOMAS COOK 0 BOOT 8, CLOTHING CO Carnival 50% to 80% off a great range ' Grounds Wrangler of Clothing and Boots The Western Original (Under the Public Stand closest to the main Carnival Map 6 I) Railway Entrance www.royalshowcom.a President's welcome FAMILIES from the city, the country and our Let the rural centres will come together for the 2008 Royal Melbourne Show. an event which is marked as a "must attend" on the calendars of hundreds of thousands of Victorians. The Royal Agricultural Society of Victoria welcomes you to its 153rd Show, the only family event in the state that unites city dwellers and country folk for 11 days of fun, festivity, entertainment, education and participation. Generations have taken home a lifetime of memories to treasure and share with family members and friends. Society patron. the Governor of Victoria David de Kretser, will officially open the Show at noon on Saturday, September 20. If you have not been to the Show for a couple of years you will be amazed by the great design and layout of the indoor and outside spaces at the Showgrounds —the results of a vast overhaul undertaken during 2005-2006. This people-friendly site has spacious walkways linking well-appointed pavilions with areas to rein, listen to music or watch amazing demonstrations while enjoying fine food and beverages. The return of horses to the Show this year will restore a crucial balance to the event, enhancing the activities on the Coca-Cola Arena with competitions and entertainment. -

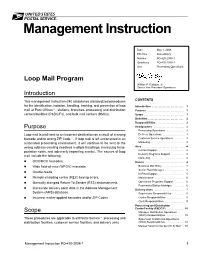

Management Instruction PO-420-2008-1 1 Definitions

R Management Instruction Date May 1, 2008 Effective Immediately Number PO-420-2008-1 Obsoletes PO-420-1999-1 Unit Processing Operations Loop Mail Program William P. Galligan, Jr. Senior Vice President Operations Introduction This management instruction (MI) establishes standardized procedures CONTENTS for the identification, isolation, handling, tracking, and prevention of loop Introduction. 1 mail at Post Officest, stations, branches, processing and distribution Purpose. 1 centers/facilities (P&DC/Fs), and bulk mail centers (BMCs). Scope. 1 Definition. 2 Responsibilities. 2 Purpose Headquarters. 2 Processing Operations. 2 Loop mail is mail sent to an incorrect destination as a result of a wrong Delivery Operations. 3 barcode and/or wrong ZIP Codet. If loop mail is left uncorrected in an Customer Service Operations. 3 automated processing environment, it will continue to be sent to the Marketing. 3 wrong address creating needless multiple handlings, increasing trans- Area. 4 portation costs, and adversely impacting service. The causes of loop In-Plant Support. 4 Delivery Programs Support. 4 mail include the following: Marketing. 4 H OCR/RCR miscodes. District. 4 H Wide field-of-view (WFOV) misreads. Business Mail Entry. 4 Senior Plant Manager. 5 H Double-feeds. In-Plant Support. 5 H Remote encoding center (REC) keying errors. Maintenance. 6 H Manually stamped Return-To-Sender (RTS) endorsements. Operations Programs Support. 6 Postmaster/Station Manager. 6 H Inaccurate delivery point data in the Address Management Delivery Units. 7 System (AMS) database. Supervisors Responsibilities. 8 H Incorrect mailer-applied barcodes and/or ZIP Codes. Carrier Responsibilities. 8 Clerk Responsibilities. 9 Processing and Distribution Center/Facility (P&DC/F).