Durham E-Theses

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sukhothai Phitsanulok Phetchabun Sukhothai Historical Park CONTENTS

UttaraditSukhothai Phitsanulok Phetchabun Sukhothai Historical Park CONTENTS SUKHOTHAI 8 City Attractions 9 Special Events 21 Local Products 22 How to Get There 22 UTTARADIT 24 City Attractions 25 Out-Of-City Attractions 25 Special Events 29 Local Products 29 How to Get There 29 PHITSANULOK 30 City Attractions 31 Out-Of-City Attractions 33 Special Events 36 Local Products 36 How to Get There 36 PHETCHABUN 38 City Attractions 39 Out-Of-City Attractions 39 Special Events 41 Local Products 43 How to Get There 43 Sukhothai Sukhothai Uttaradit Phitsanulok Phetchabun Phra Achana, , Wat Si Chum SUKHOTHAI Sukhothai is located on the lower edge of the northern region, with the provincial capital situated some 450 kms. north of Bangkok and some 350 kms. south of Chiang Mai. The province covers an area of 6,596 sq. kms. and is above all noted as the centre of the legendary Kingdom of Sukhothai, with major historical remains at Sukhothai and Si Satchanalai. Its main natural attraction is Ramkhamhaeng National Park, which is also known as ‘Khao Luang’. The provincial capital, sometimes called New Sukhothai, is a small town lying on the Yom River whose main business is serving tourists who visit the Sangkhalok Museum nearby Sukhothai Historical Park. CITY ATTRACTIONS Ramkhamhaeng National Park (Khao Luang) Phra Mae Ya Shrine Covering the area of Amphoe Ban Dan Lan Situated in front of the City Hall, the Shrine Hoi, Amphoe Khiri Mat, and Amphoe Mueang houses the Phra Mae Ya figure, in ancient of Sukhothai Province, this park is a natural queen’s dress, said to have been made by King park with historical significance. -

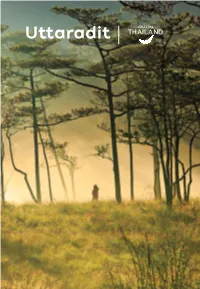

Uttaradit Uttaradit Uttaradit

Uttaradit Uttaradit Uttaradit Namtok Sai Thip CONTENTS HOW TO GET THERE 7 ATTRACTIONS 8 Amphoe Mueang Uttaradit 8 Amphoe Laplae 11 Amphoe Tha Pla 16 Amphoe Thong Saen Khan 18 Amphoe Nam Pat 19 EVENTS & FESTIVALS 23 LOCAL PRODUCTS AND SOUVENIRS 25 INTERESTING ACTIVITIES 27 Agro-tourism 27 Golf Course 27 EXAMPLES OF TOUR PROGRAMMES 27 FACILITIES IN UTTARADIT 28 Accommodations 28 Restaurants 30 USEFUL CALLS 32 Wat Chedi Khiri Wihan Uttaradit Uttaradit has a long history, proven by discovery South : borders with Phitsanulok. of artefacts, dating back to pre-historic times, West : borders with Sukhothai. down to the Ayutthaya and Thonburi periods. Mueang Phichai and Sawangkhaburi were HOW TO GET THERE Ayutthaya’s most strategic outposts. The site By Car: Uttaradit is located 491 kilometres of the original town, then called Bang Pho Tha from Bangkok. Two routes are available: It, which was Mueang Phichai’s dependency, 1. From Bangkok, take Highway No. 1 and No. 32 was located on the right bank of the Nan River. to Nakhon Sawan via Phra Nakhon Si Ayutthaya, It flourished as a port for goods transportation. Ang Thong, Sing Buri, and Chai Nat. Then, use As a result, King Rama V elevated its status Highway No. 117 and No. 11 to Uttaradit via from Tambon or sub-district into Mueang or Phitsanulok. town but was still under Mueang Phichai. King 2. From Bangkok, drive to Amphoe In Buri via Rama V re-named it Uttaradit, literally the Port the Bangkok–Sing Buri route (Highway No. of the North. Later Uttaradit became more 311). -

Informal Relationship Patterns Among Staff of Local Health and Non-Health Organizations in Thailand Mano Maneechay1,2 and Krit Pongpirul1,3,4,5*

Maneechay and Pongpirul BMC Health Services Research (2015) 15:113 DOI 10.1186/s12913-015-0781-8 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Informal relationship patterns among staff of local health and non-health organizations in Thailand Mano Maneechay1,2 and Krit Pongpirul1,3,4,5* Abstract Background: Co-operation among staff of local government agencies is essential for good local health services system, especially in small communities. This study aims to explore possible informal relationship patterns among staff of local health and non-health organizations in the context of health decentralization in Thailand. Methods: Tambon Health Promoting Hospital (THPH) and Sub-district Administrative Organization (SAO) represented local health and non-health organizations, respectively. Based on the finding from qualitative interview of stakeholders, a questionnaire was developed to explore individual and organizational characteristics and informal relationships between staff of both organizations. Respondents were asked to draw ‘relationship lines’ between each staff position of health and non-health organizations. ‘Degree of relationship’ was assessed from the number that respondent assigned to each of the lines (1, friend; 2, second-degree relative; 3, first-degree relative; 4, spouse). The questionnaire was distributed to 748 staff of local health and non-health organizations in 378 Tambons. A panel of seven experts was asked to look at all responded questionnaires to familiarize with the content then discussed about possible categorization of the patterns. Results: Responses were received from 73.0% (276/378) Tambons and 59.0% (441/748) staff. The informal relationships were classified into four levels: strong, moderate, weak and no informal relationship, mainly because of potential impact on local health services system. -

General Information Current Address 89 Moo 5, Tambon Wat Phra Bat

Mr. Chatbhumi Amnatnua The Hostess The Political Science Association of Kasetsart University General Information Current Address 89 Moo 5, Tambon Wat Phra Bat Tha Uthen District Nakhon Phanom Province 48120 Date of Birth April 1, 1981 Birth Place Nakhon Phanom Marital Status: Single Nationality: Thai Nationality: Thai Religion: Buddhist Mobile Phone 063-903-0009 Email: [email protected] The formal workplace: The administrative office of That Phanom District, Nakhon Phanom Province (Address: 299 Moo 6 Tambol That Phanom Amphoe That Phanom Nakhon Phanom 48110, Tel: 042-532-023) Educational Background 1. Primary School, Ban Pak Thuy School, 1994 2. Junior High School Nakhon Phanom Wittayakhom School, 1997 3. High School Nakhon Phanom Wittayakhom School, 2000 4. Undergraduate Bachelor of Laws Sripatum University, 2004 5. Master's Degree Master of Arts (Political Science), Kasetsart University, 2008 Career History (Start working - present) 1. Analyst position, Policy and Action Plan of National Economic and Social Advisory Council 1 June 2009 2. Policy Analyst positions. Policy and Action Plan of National Economic and Social Advisory 1 June 2013 3. District Officer (Administrative Officer) of Krok Phra District Department of Administration 1 July 2015 - 15 May 2016 4. District bailiff (administrative officer) in charge of Tha Tako district Department of Provincial Administration 16 May 2016 - 4 June 2016 5. District Bailiff (Administrative Officer) at Phraya Khiri District Department of Administration June 5, 2560 - July 10, 2560 6. The district secretary (the competent administrator), the administrator of the district. Department of Administration 11 July 2560 - present Profile of the Past Seminar and Workshop 1. Department of District Administration, No.218, BE 2556, College of Administration 2. -

Levi Strauss & Co. Factory List

Levi Strauss & Co. Factory List Published : November 2019 Total Number of LS&Co. Parent Company Name Employees Country Factory name Alternative Name Address City State Product Type (TOE) Initiatives (Licensee factories are (Workers, Staff, (WWB) blank) Contract Staff) Argentina Accecuer SA Juan Zanella 4656 Caseros Accessories <1000 Capital Argentina Best Sox S.A. Charlone 1446 Federal Apparel <1000 Argentina Estex Argentina S.R.L. Superi, 3530 Caba Apparel <1000 Argentina Gitti SRL Italia 4043 Mar del Plata Apparel <1000 Argentina Manufactura Arrecifes S.A. Ruta Nacional 8, Kilometro 178 Arrecifes Apparel <1000 Argentina Procesadora Serviconf SRL Gobernardor Ramon Castro 4765 Vicente Lopez Apparel <1000 Capital Argentina Spring S.R.L. Darwin, 173 Federal Apparel <1000 Asamblea (101) #536, Villa Lynch Argentina TEXINTER S.A. Texinter S.A. B1672AIB, Buenos Aires Buenos Aires <1000 Argentina Underwear M&S, S.R.L Levalle 449 Avellaneda Apparel <1000 Argentina Vira Offis S.A. Virasoro, 3570 Rosario Apparel <1000 Plot # 246-249, Shiddirgonj, Bangladesh Ananta Apparels Ltd. Nazmul Hoque Narayangonj-1431 Narayangonj Apparel 1000-5000 WWB Ananta KASHPARA, NOYABARI, Bangladesh Ananta Denim Technology Ltd. Mr. Zakaria Habib Tanzil KANCHPUR Narayanganj Apparel 1000-5000 WWB Ananta Ayesha Clothing Company Ltd (Ayesha Bangobandhu Road, Tongabari, Clothing Company Ltd,Hamza Trims Ltd, Gazirchat Alia Madrasha, Ashulia, Bangladesh Hamza Clothing Ltd) Ayesha Clothing Company Ltd( Dhaka Dhaka Apparel 1000-5000 Jamgora, Post Office : Gazirchat Ayesha Clothing Company Ltd (Ayesha Ayesha Clothing Company Ltd(Unit-1)d Alia Madrasha, P.S : Savar, Bangladesh Washing Ltd.) (Ayesha Washing Ltd) Dhaka Dhaka Apparel 1000-5000 Khejur Bagan, Bara Ashulia, Bangladesh Cosmopolitan Industries PVT Ltd CIPL Savar Dhaka Apparel 1000-5000 WWB Epic Designers Ltd 1612, South Salna, Salna Bazar, Bangladesh Cutting Edge Industries Ltd. -

Providers-Thailand.Pdf

City Provider Name Address Line 1 Address Line 2 Province/State Zip Code Phone Provider Type Bangkok Vejthani Hospital 1 Ladprao Road 111 Klong-Chan, 10240 66.2.734.0000 Hospital Bangkapi Bangkok Samitivej Sukhumvit 133 Sukhumvit 49, Klongtan Vadhana 10110 66.2.022.2900 Hospital Hospital Nua Bangkok Bangkok Hospital 2 Soi Soonvijai 7, New Huay Kwang 10310 66.2.310.3000 Hospital Petchburi Road Bangkok Bumrungrad International 33 Sukumvit Road 3 (Soi Wattana 10110 66.2.066.8888 Hospital Hospital Nana Nua) Bangkok Aetna Family Clinic, 39/626 Mu 3, Samakkee Bangtarad Nonthabur 11120 66.2.960.4216 Clinic Nichada Road, Pakkred Bangkok Samitivej Srinakarin 488 Srinakarin Road Suanluang 10250 66.2.378.9018 Hospital Hospital Bangkok Samitivej Srinakarin 488 Srinakarin Road, 3rd Suanluang 10250 66.2.731.7000 Hospital Children's Hospital Floor Bangkok Bangkok Hospital China 624 Yaowarat Road Samphanthawo 10100 662.118.7888 Hospital Town ng Bangkok Paolo Hospital 670/1 Phaholyothin Road Samsennai Phayathai 10400 66.2271.7000 Hospital Phaholyothin X11247 Bangkok BNH Hospital 9/1, Convent Road Silom 10500 66.2.022.0700 Hospital Bangkok Global Doctor Clinic - Interchange Tower Asoke, 399 Sukhumvit Road 10110 66.2.611.2929 Hospital Bangkok - Sukhumvit Ground Floor Bangkok Global Doctor Clinic - Shop 4, G/F, Holiday Inn 981 Silom Road 10500 66.2.236.8444 Hospital Bangkok - Silom Silom Hotel Bangkok Medconsult Clinic The Racquet Club, 3th Floor Sukhumvit Soi 49/9 10110 66.2.018.7855 Clinic Bophut Bangkok Hospital Samui 57 Moo 3, Thaweerat Surat Thani 84320 66.77.429.500 Hospital Phakdee Road Chanthab Bangkok Hospital 25/14 Thaluang Road Watmai, Muang 22000 66.39.351.467 Hospital uri Chanthaburi Chiang Bangkok Hospital 88/9 Moo 6, Chiang Mai- Tambon Nong Pa 50000 66.52.089888 Hospital Mai Chiangmai Lampang Road Khrang Chonburi Samitivej Chonburi 888/88 Village No. -

No.1 Thai-Yunnan Project Newsletter June 1988

[Last updated: 28 April 1992] ----------------------------------------------------------------------------- No.1 Thai-Yunnan Project Newsletter June 1988 Number One June 1988 participants Mr. Anuchat Poungsomlee, Environmental studies Mr. S. Bamber, Traditional healing, medical botany Dr. P. Bellwood, Prehistory Mr. E.C. Chapman, Geography, rural economy Ms. Cholthira Satyawadhna, Anthrop., Mon-Khmer sps. Dr. Marybeth Clark, Hmong & Vietnamese linguistics Mr. Andrew Cornish, Economic Anthrop. Dr. Jennifer Cushman, Chinese in SE Asia Dr. Anthrony Diller, Linguistics, Tai Dr. John Fincher, History Ms. Kritaya Archavanitkul, Demography Dr. Helmut Loofs-Wissowa, Archaeology, bronze age Dr. David Marr, Viet. history Dr. Douglas Miles, Anthropology, Yao Mr. George Miller, Library Dr. Jean Mulholland, Ethno- pharmacology Mrs. Susan Prentice, Library Mr. Preecha Juntanamalaga, Tai languages, history Ms. Somsuda Rutnin, Prehistory & Archaeology Dr. L. Sternstein, Geography, population Dr. B.J. Terwiel, Ethnography, Tai ethnohistory Ms. Jill Thompson, Archaeology, ethnobotany Dr. Esta Ungar, Sino- Vietnamese relations Dr. Jonathon Unger, Sociology Dr. Gehan Wijeyewardene, Anthropology, Tai Mr. Ian Wilson, Political Science Prof. Douglas Yen, Prehistory, ethnobotany The Thai-Yunnan Project The Thai-Yunnan Project is concerned with the study of the peoples of the border regions betwen the Peoples Republic of China and the mainland states of Southeast Asia (Vietnam, Laos, Thailand and Burma). The project encompasses the study of the languages, cultures and societies of the constituent peoples as well as of their inter-relations within and across national boundaries. Practicalities make it necessary to focus our immediate interests on the more southern regions of Yunnan and northern Thailand. Academic knowledge of Yunnan, particularly as represented in published Western literature is superficial; yet in theoretical and strategic terms it is an area of great interest. -

Learning from the Recent Past Extreme Climatic Events for Future Planning

Addressing Non-economic Losses and Damages Associated with Climate Change: Learning from the Recent Past Extreme Climatic Events for Future Planning Yohei Chiba and S.V.R.K. Prabhakar Addressing Non-economic Losses and Damages Associated with Climate Change: Learning from the Recent Past Extreme Climatic Events for Future Planning Edited by: Yohei Chiba and S.V.R.K. Prabhakar Contact [email protected] Institute for Global Environmental Strategies (IGES), Hayama, Japan APN website: http://www.apn-gcr.org/resources/items/show/1943 IGES website: https://www.iges.or.jp/en/natural-resource/ad/landd.html Suggested Citation Chiba, Y. and S.V.R.K. Prabhakar (Eds.). 2017. Addressing Non-economic Losses and Damages Associated with Climate Change: Learning from the Recent Past Extreme Climatic Events for Future Planning. Kobe, Japan: Asia-Pacific Network for Global Change Research (APN) and Institute for Global Environmental Strategies (IGES). Copyright © 2017 Asia-Pacific Network for Global Change Research APN seeks to maximise discoverability and use of its knowledge and information. All publications are made available through its online repository “APN E-Lib” (www.apn-gcr.org/resources/). Unless otherwise indicated, APN publications may be copied, downloaded and printed for private study, research and teaching purposes, or for use in non-commercial products or services. Appropriate acknowledgement of APN as the source and copyright holder must be given, while APN’s endorsement of users’ views, products or services must not be implied in any way. For reuse requests: http://www.apn-gcr.org/?p=10807 Table of Content List of Contributors ........................................................................................................ iii Acknowledgments ........................................................................................................ -

Central-Local Government Relations in Thailand

Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Management Report2012 Thailand PublicFinancial Delivery Service Improving Thailand Relations in Government Central-Local Central-Local Government Relations in Thailand Improving Service Delivery Thailand Public Financial Management Report 2012 ©2012 The World Bank The World Bank 30th Floor, Siam Tower 989 Rama 1 Road, Pathumwan Bangkok 10330, Thailand (66) 0-2686-8300 www.worldbank.org/th This volume is a product of the staff of the World Bank with external contributions. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this volume do not necessarily reflect the views of The World Bank, its Board of Executive Directors, or the governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judge- ment on the part of The World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. Rights and Permissions The material in this publication is copyrighted. Copying and/or transmitting portions or all of this work without permission may be a violation of applicable law. The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank encourages dissemination of its work and will normally grant permission to reproduce portions of the work promptly. For permission to photocopy or reprint any part of this work, please send a request with complete information to the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc., 222 Rose- wood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, USA, telephone 978-750-8400, fax 978-750-4470, www.copyright.com. -

2016/12/8 更新 No NAME ADDRESS 3 CPF (THAILAND) PUBLIC

タイ(生鮮家きん肉) 2016/12/8 更新 No NAME ADDRESS 48 MOO 9, SUWINTHAWONG ROAD, SANSAB, MINBURI, 3 CPF (THAILAND) PUBLIC COMPANY LIMITED BANGKOK 10510, THAILAND 128 NAWAMIN ROAD, RAMINRA, KHAN NA YAO, BANGKOK 4 SAHA FARMS CO., LTD. 10230, THAILAND 30/3 MOO 3, SUWINTHAWONG ROAD, LAMPAKCHEE, 5 CPF (THAILAND) PUBLIC COMPANY LIMITED NONG JOK, BANGKOK 10530, THAILAND 87 MOO 9, BUDDHAMONTHON 5 ROAD, SAMPHRAN DISTRICT, 6 LAEMTHONG FOOD PRODUCTS CO., LTD. NAKHONPATHOM 73210, THAILAND 54 MOO 5, PAHOLYOTHIN RD., KHLONG NUENG, KHLONG LUANG, PATHUMTHANI 7 CENTRAL POULTRY PROCESSING CO., LTD. 12120, THAILAND 4/2 MOO 7, SOI SUKAPIBAL 2, BUDHAMONTHON 5 ROAD, OM NOI, KRATHUM BAEN, 10 BETTER FOODS CO., LTD. SAMUT SAKHON 74130, THAILAND 209 MOO 1, TEPARAK RD., KM.20.5, BANG SAO THONG, SAMUT PRAKAN 10540, 11 GFPT PUBLIC COMPANY LIMITED THAILAND 18/1 MOO 12, LANGWATBANGPLEEYAINAI RD., BANGPHLIYAI, BANGPHLI, 14 BANGKOK RANCH PUBLIC CO., LTD. SAMUTPRAKAN 10540, THAILAND SOUTH-EAST ASIAN PACKAGING AND CANNING CO., 233 MOO 4, SOI 2 BANPOO INDUSTRIAL ESTATE, AMPHOE MUANG, SAMUTPRAKARN 17 LTD. PROVINCE 10280, THAILAND 111 SOI BANGNA-TRAD 20, BANGNA-TRAD ROAD, BANGNA, BANGKOK 10260, 18 CPF (THAILAND) PUBLIC COMPANY LIMITED THAILAND 20/2 MOO 3, SUWINTHAWONG ROAD, SANSAB, MINBURI, BANGKOK 10510, 21 CPF (THAILAND) PUBLIC COMPANY LIMITED THAILAND 150 MOO 7, TANDIEW, KAENGKHOI, SARABURI 18110, 23 CPF (THAILAND) PUBLIC COMPANY LIMITED THAILAND 69 MOO 6, MUAK LEK-WANG MUANG RD., KAMPRAN, 25 SUN FOOD INTERNATIONAL CO., LTD. WANG MUANG, SARABURI 18220, THAILAND 101/1 NAVANAKORN INDUSTRIAL ESTATE, 27 SNACKY THAI CO., LTD. PHAHOL YOTHIN RD., KLONG 1, KHLONG LUANG, PATHUM THANI 12120, THAILAND 1/21 MOO 5, ROJANA INDUSTRIAL PARK, KANHAM, UTHAI, 29 THAI NIPPON FOODS CO., LTD. -

Attacks on Health Care

Attacks on Health Care Monthly News Brief July SHCC Attacks on Health Care 2020 The section aligns with the definition of attacks on health care used by the Safeguarding Health in Conflict Coalition (SHCC). This monthly digest Africa comprises threats and Cameroon violence as well as protests 06 July 2020: In Mamfe city, Southwest region, seven health workers and other events affecting the were detained by security forces during a security operation in the area. delivery of and access to Source: Human Rights Watch health care. Around 07 July 2020: In Kumbo city, Bui district, Northwest region, It is prepared by Insecurity Shisong Hospital was stormed by members of the military who Insight from information threatened to remove patients they suspected to be Ambazonia available in open sources. fighters. A nurse was almost beaten for defending the medical The incidents reported are not a treatment of people without discrimination. Source: Mimimefo Info complete nor a representative list of all events that affected the 09 July 2020: Near Kumba city, Meme department, South West region, provision of health care and a Cameroonian volunteer community health worker employed by MSF have not been independently was kidnapped and killed. An Ambazonian separatist group fighting verified government forces in the region first claimed responsibility in a video circulating on social media, before a denial from the political branch of Access data from the Attacks on the independence movement in exile. In the video, the aid worker was Health Care Monthly News Brief accused by these fighters of “being a spy in the pay of the government”. -

Participation of Local People in Water Management: Evidence from the Mae Sa Watershed, Northern Thailand

EPTD Discussion Paper No. 128 PARTICIPATION OF LOCAL PEOPLE IN WATER MANAGEMENT: EVIDENCE FROM THE MAE SA WATERSHED, NORTHERN THAILAND Helene Heyd and Andreas Neef Environment and Production Technology Division International Food Policy Research Institute 2033 K Street, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20006 U.S.A. December 2004 Copyright © 2004: International Food Policy Research Institute EPTD Discussion Papers contain preliminary material and research results, and are circulated prior to a full peer review in order to stimulate discussion and critical comment. It is expected that most Discussion Papers will eventually be published in some other form, and that their content may also be revised. ABSTRACT In the early 1990s, Thailand launched an ambitious program of decentralized governance, conferring greater responsibilities upon sub-district administrations and providing fiscal opportunities for local development planning. This process was reinforced by Thailand’s new Constitution of 1997, which explicitly assures individuals, communities and local authorities the right to participate in the management of natural resources. Drawing on a study of water management in the Mae Sa watershed, northern Thailand, this study analyzes to what extent the constitutional right for participation has been put into practice. To this end, a stakeholder analysis was conducted in the watershed, with a focus on the local people’s interests and strategies in water management and the transformation of participatory policies through government agencies at the local level. Government line departments were categorized into development- and conservation-oriented agencies. While government officers stressed the importance of stakeholder inclusion and cooperation with the local people, there is a sharp contrast between the official rhetoric and the reality on the ground.