PDAAR451.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Electricity Needs Assessment

Electricity needs Assessment Atoll (after) Island boxes details Remarks Remarks Gen sets Gen Gen set 2 Gen electricity electricity June 2004) June Oil Storage Power House Availability of cable (before) cable Availability of damage details No. of damaged Distribution box distribution boxes No. of Distribution Gen set 1 capacity Gen Gen set 1 capacity Gen set 2 capacity Gen set 3 capacity Gen set 4 capacity Gen set 5 capacity Gen Gen set 2 capacity set 2 capacity Gen set 3 capacity Gen set 4 capacity Gen set 5 capacity Gen Total no. of houses Number of Gen sets Gen of Number electric cable (after) cable electric No. of Panel Boards Number of DamagedNumber Status of the electric the of Status Panel Board damage Degree of Damage to Degree of Damage to Degree of Damaged to Population (Register'd electricity to the island the to electricity island the to electricity Period of availability of Period of availability of HA Fillladhoo 921 141 R Kandholhudhoo 3,664 538 M Naalaafushi 465 77 M Kolhufushi 1,232 168 M Madifushi 204 39 M Muli 764 134 2 56 80 0001Temporary using 32 15 Temporary Full Full N/A Cables of street 24hrs 24hrs Around 20 feet of No High duty equipment cannot be used because 2 the board after using the lights were the wall have generators are working out of 4. reparing. damaged damaged (2000 been collapsed boxes after feet of 44 reparing. cables,1000 feet of 29 cables) Dh Gemendhoo 500 82 Dh Rinbudhoo 710 116 Th Vilufushi 1,882 227 Th Madifushi 1,017 177 L Mundoo 769 98 L Dhabidhoo 856 130 L Kalhaidhoo 680 94 Sh Maroshi 834 166 Sh Komandoo 1,611 306 N Maafaru 991 150 Lh NAIFARU 4,430 730 0 000007N/A 60 - N/A Full Full No No 24hrs 24hrs No No K Guraidhoo 1,450 262 K Huraa 708 156 AA Mathiveri 73 2 48KW 48KW 0002 48KW 48KW 00013 breaker, 2 ploes 27 2 some of the Full Full W/C 1797 Feet 24hrs 18hrs Colappes of the No Power house, building intact, only 80KW generator set of 63A was Distribution south east wall of working. -

Population and Housing Census 2014

MALDIVES POPULATION AND HOUSING CENSUS 2014 National Bureau of Statistics Ministry of Finance and Treasury Male’, Maldives 4 Population & Households: CENSUS 2014 © National Bureau of Statistics, 2015 Maldives - Population and Housing Census 2014 All rights of this work are reserved. No part may be printed or published without prior written permission from the publisher. Short excerpts from the publication may be reproduced for the purpose of research or review provided due acknowledgment is made. Published by: National Bureau of Statistics Ministry of Finance and Treasury Male’ 20379 Republic of Maldives Tel: 334 9 200 / 33 9 473 / 334 9 474 Fax: 332 7 351 e-mail: [email protected] www.statisticsmaldives.gov.mv Cover and Layout design by: Aminath Mushfiqa Ibrahim Cover Photo Credits: UNFPA MALDIVES Printed by: National Bureau of Statistics Male’, Republic of Maldives National Bureau of Statistics 5 FOREWORD The Population and Housing Census of Maldives is the largest national statistical exercise and provide the most comprehensive source of information on population and households. Maldives has been conducting censuses since 1911 with the first modern census conducted in 1977. Censuses were conducted every five years since between 1985 and 2000. The 2005 census was delayed to 2006 due to tsunami of 2004, leaving a gap of 8 years between the last two censuses. The 2014 marks the 29th census conducted in the Maldives. Census provides a benchmark data for all demographic, economic and social statistics in the country to the smallest geographic level. Such information is vital for planning and evidence based decision-making. Census also provides a rich source of data for monitoring national and international development goals and initiatives. -

Villas and Residences | Club Intercontinental Benefits | Opening Special | Getting Here

VILLAS AND RESIDENCES | CLUB INTERCONTINENTAL BENEFITS | OPENING SPECIAL | GETTING HERE RESTAURANTS AND BARS | OCEAN CONSERVATION PROGRAM & COLLABORATION WITH MANTA TRUST | AVI SPA & WELLNESS AND KIDS CLUB A new experience lies ahead of you this September with the opening of the new InterContinental Maldives Maamunagau Resort. Spread over a private island with lush tropical greenery, InterContinental Maldives Maamunagau Resort seamlessly blends with the awe-inspiring natural beauty of the island. Resort facilities include: • 81 Villas & Residences • 6 restaurants and bars • Club InterContinental benefits • “The Retreat” - an adults only lounge • An overwater spa • 5 Star PADI certified diver center oering courses and daily expeditions with an on-site Marine Biologist • Planet Trekkers children’s facility VILLAS AND RESIDENCES Experience Maldives’ breathtaking vistas from each of the spacious 81 Beach, Lagoon and Overwater Villas and Residences at the InterContinental Maldives Maamunagau Resort. Choose soothing lagoon or dramatic ocean views with a perfect vantage point from your private terrace for a spectacular Bedroom - Overwater Pool Villa Outdoor Pool Deck - Overwater Pool Villa sunrise or sunset. Each Villa or Residence is tastefully designed encapsulating the needs of the modern nomad infused with distinct Maldivian design; featuring one, two or three separate bedrooms, lounge with an ensuite complemented by a spacious terrace overlooking the ocean or lagoon with a private pool. GO TO TOP Livingroom - Lagoon Pool Villa Bedroom - One -

List of MOE Approved Non-Profit Public Schools in the Maldives

List of MOE approved non-profit public schools in the Maldives GS no Zone Atoll Island School Official Email GS78 North HA Kelaa Madhrasathul Sheikh Ibrahim - GS78 [email protected] GS39 North HA Utheem MadhrasathulGaazee Bandaarain Shaheed School Ali - GS39 [email protected] GS87 North HA Thakandhoo Thakurufuanu School - GS87 [email protected] GS85 North HA Filladhoo Madharusathul Sabaah - GS85 [email protected] GS08 North HA Dhidhdhoo Ha. Atoll Education Centre - GS08 [email protected] GS19 North HA Hoarafushi Ha. Atoll school - GS19 [email protected] GS79 North HA Ihavandhoo Ihavandhoo School - GS79 [email protected] GS76 North HA Baarah Baarashu School - GS76 [email protected] GS82 North HA Maarandhoo Maarandhoo School - GS82 [email protected] GS81 North HA Vashafaru Vasahfaru School - GS81 [email protected] GS84 North HA Molhadhoo Molhadhoo School - GS84 [email protected] GS83 North HA Muraidhoo Muraidhoo School - GS83 [email protected] GS86 North HA Thurakunu Thuraakunu School - GS86 [email protected] GS80 North HA Uligam Uligamu School - GS80 [email protected] GS72 North HDH Kulhudhuffushi Afeefudin School - GS72 [email protected] GS53 North HDH Kulhudhuffushi Jalaaludin school - GS53 [email protected] GS02 North HDH Kulhudhuffushi Hdh.Atoll Education Centre - GS02 [email protected] GS20 North HDH Vaikaradhoo Hdh.Atoll School - GS20 [email protected] GS60 North HDH Hanimaadhoo Hanimaadhoo School - GS60 -

ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT for the Construction of a Slipway in Goidhoo Island, Shaviyani Atoll, Maldives

ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT For the construction of a slipway in Goidhoo Island, Shaviyani Atoll, Maldives Photo: Water Solutions Proposed by: 3L Construction PVT.LTD Prepared by: Hassan Shah (EIA P02/2007) For Water Solutions Pvt. Ltd., Maldives May 2018 BLANK PAGE EIA For the construction of a slipway in Goidhoo Island, Shaviyani Atoll 1 Table of contents 1 Table of contents ...................................................................................................... 3 2 List of Figures and Tables ........................................................................................ 7 3 Declaration of the consultants .................................................................................. 8 4 Proponents Commitment and Declaration ............................................................... 9 5 Non-Technical Summary ....................................................................................... 13 6 Introduction ............................................................................................................ 15 6.1 Structure of the EIA ........................................................................................... 15 6.2 Aims and Objectives of the EIA ........................................................................ 15 6.3 EIA Implementation .......................................................................................... 15 6.4 Rational for the formulation of alternatives ....................................................... 15 6.5 Terms of Reference........................................................................................... -

Conservation and Population Ecology of Manta Rays in the Maldives

Conservation and Population Ecology of Manta Rays in the Maldives Guy Mark William Stevens Doctor of Philosophy University of York Environment August 2016 2 Abstract This multi-decade study on an isolated and unfished population of manta rays (Manta alfredi and M. birostris) in the Maldives used individual-based photo-ID records and behavioural observations to investigate the world’s largest known population of M. alfredi and a previously unstudied population of M. birostris. This research advances knowledge of key life history traits, reproductive strategies, population demographics and habitat use of M. alfredi, and elucidates the feeding and mating behaviour of both manta species. M. alfredi reproductive activity was found to vary considerably among years and appeared related to variability in abundance of the manta’s planktonic food, which in turn may be linked to large-scale weather patterns such as the Indian Ocean Dipole and El Niño-Southern Oscillation. Key to helping improve conservation efforts of M. alfredi was my finding that age at maturity for both females and males, estimated at 15 and 11 years respectively, appears up to 7 – 8 years higher respectively than previously reported. As the fecundity of this species, estimated at one pup every 7.3 years, also appeared two to more than three times lower than estimates from studies with more limited data, my work now marks M. alfredi as one of the world’s least fecund vertebrates. With such low fecundity and long maturation, M. alfredi are extremely vulnerable to overfishing and therefore needs complete protection from exploitation across its entire global range. -

Findings of the Vulnerability and Capacity Assessment in Maduvvaree and Meedhoo

PROVENTION CONSORTIUM Community Risk Assessment and Action Planning project MALDIVES – Maduvvaree and Meedhoo © www.strathlorntravel.co.uk Findings of the Vulnerability and Capacity Assessment In Maduvvaree and Meedhoo CRA Toolkit This case study is part of a broader ProVention Consortium initiative aimed at collecting and analyzing community risk assessment cases. For CASE STUDY more information on this project, see www.proventionconsortium.org. Bibliographical reference: International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies, Findings of the Vulnerability Capacity Assessment Community: Maduvvaree and Meedhoo, IFRC, Geneva, Switzerland (2006). Click-on reference to the ReliefWeb country file for Maldives: http://www.reliefweb.int/rw/dbc.nsf/doc104?OpenForm&rc=3&cc=mdv Note: A Guidance Note has been developed for this case study. It contains an abstract, analyzes the main findings of the study, provides contextual and strategic notes and highlights the main lessons learned from the case. The guidance note has been developed by Stephanie Bouris in close collaboration with the author(s) of the case study and the organization(s) involved. International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies Maldives – Federation Secretariat and Country Delegation - and Communities from Maduvvarey and Meedhoo VCA Vulnerability and Capacity Assessment 23th – 29th June 2006 1. Introduction: The disaster risk scenario for the Maldives can be described as moderate in general. Despite this, the Maldives was among the most severely affected countries hit by the Asian Tsunami on December 26th 2004. The Maldives experiences moderate risk conditions owing to a low probability of hazard occurrence and high vulnerability from exposure due to geographical, topographical and socio-economic factors. -

37327 Public Disclosure Authorized

37327 Public Disclosure Authorized REPUBLIC OF THE MALDIVES Public Disclosure Authorized TSUNAMI IMPACT AND RECOVERY Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized JOINT NEEDS ASSESSMENT WORLD BANK - ASIAN DEVELOPMENT BANK - UN SYSTEM ki QU0 --- i 1 I I i i i i I I I I I i Maldives Tsunami: Impact and Recovery. Joint Needs Assessment by World Bank-ADB-UN System Page 2 ABBREVIATIONS ADB Asian Development Bank DRMS Disaster Risk Management Strategy GDP Gross Domestic Product GoM The Government of Maldives IDP Internally displaced people IFC The International Finance Corporation IFRC International Federation of Red Cross IMF The International Monetary Fund JBIC Japan Bank for International Cooperation MEC Ministry of Environment and Construction MFAMR Ministry of Fisheries, Agriculture, and Marine Resources MOH Ministry of Health NDMC National Disaster Management Center NGO Non-Governmental Organization PCB Polychlorinated biphenyls Rf. Maldivian Rufiyaa SME Small and Medium Enterprises STELCO State Electricity Company Limited TRRF Tsunami Relief and Reconstruction Fund UN United Nations UNFPA The United Nations Population Fund UNICEF The United Nations Children's Fund WFP World Food Program ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This report was prepared by a Joint Assessment Team from the Asian Development Bank (ADB), the United Nations, and the World Bank. The report would not have been possible without the extensive contributions made by the Government and people of the Maldives. Many of the Government counterparts have been working round the clock since the tsunami struck and yet they were able and willing to provide their time to the Assessment team while also carrying out their regular work. It is difficult to name each and every person who contributed. -

Job Applicants' Exam Schedule February 2016

Human Resource Management Section Maldives Customs Service Date: 8/2/2016 Job Applicants' Exam Schedule February 2016 Exam Group 1 Exam Venue: Customs Head Office 8th Floor Date: 14 February 2016 Time: 09:00 AM # Full Name NID Permanent Address 1 Hussain Ziyad A290558 Gumreege/ Ha. Dhidhdhoo 2 Ali Akram A269279 Olhuhali / HA. Kelaa 3 Amru Mohamed Didi A275867 Narugisge / Gn.Fuvahmulah 4 Fathimath Rifua A287497 Chaman / Th.Kinbidhoo 5 Ausam Mohamed Shahid A300096 Mercy / Gdh.Gadhdhoo 6 Khadheeja Abdul Azeez A246131 Foniluboage / F.Nilandhoo 7 Hawwa Raahath A294276 Falhoamaage / S.Feydhoo 8 Mohamed Althaf Ali A278186 Hazeleen / S.Hithadhoo 9 Aishath Manaal Khalid A302221 Sereen / S.Hithadhoo 10 Azzam Ali A296340 Dhaftaru. No 6016 / Male' 11 Aishath Suha A258653 Athamaage / HA.filladhoo 12 Shamra Mahmoodf A357770 Ma.Rinso 13 Hussain Maaheen A300972 Hazaarumaage / Gdh.Faresmaathodaa 14 Reeshan Mohamed A270388 Bashimaa Villa / Sh.Maroshi 15 Meekail Ahmed Nasym A165506 H. Sword / Male' 16 Mariyam Aseela A162018 Gulraunaage / R. Alifushi 17 Mohamed Siyah A334430 G.Goidhooge / Male' 18 Maish Mohamed Maseeh A322821 Finimaage / SH.Maroshi 19 Shahim Saleem A288096 Shabnamge / K.Kaashidhoo 20 Mariyam Raya Ahmed A279017 Green villa / GN.Fuvahmulah 21 Ali Iyaz Rashid A272633 Chamak / S.Maradhoo Feydhoo 22 Adam Najeedh A381717 Samandaru / LH.Naifaru 23 Aishath Zaha Shakir A309199 Benhaage / S.Hithadhoo 24 Aishath Hunaifa A162080 Reehussobaa / R.Alifushi 25 Mubthasim Mohamed Saleem A339329 Chandhaneege / GA.Dhevvadhoo 26 Mohamed Thooloon A255587 Nooraanee Villa / R. Alifushi 27 Abdulla Mubaah A279986 Eleyniri / Gn.Fuvahmulah 28 Mariyam Hana A248547 Nookoka / R.Alifushi 29 Aishath Eemaan Ahmed A276630 Orchid Fehi / S.Hulhudhoo 30 Haroonul Rasheed A285952 Nasrussaba / Th. -

COUNTRY LEVEL EVALUATION Maldives

COUNTRY LEVEL EVALUATION Maldives Draft Final Report VOLUME II: ANNEXES 26th November 2010 Evaluation carried out on behalf of the European Commission Framework contract for Multi-country thematic and regional/country-level strategy evaluation studies and synthesis in the area of external co-operation Italy LOT 4: Evaluation of EC geographic co-operation strategies for countries/regions in Asia, Latin America, the Aide à la Décision Economique Southern Mediterranean and Eastern Europe (the area Belgium of the New Neighbourhood Policy) Ref.: EuropeAid/122888/C/SER/Multi Particip GmbH Germany Evaluation of the European Commission‟s Co-operation with Deutsches Institut für Entwicklungspolitik Maldives Germany Country Level Evaluation Overseas Development Institute Contract n° EVA 2007/geo-non-ACP United Kingdom Draft Final Report VOLUME II: ANNEXES European Institute for Asian Studies Belgium Instituto Complutense de Estudios Internacionales Spain A consortium of DRN, ADE, Particip, DIE, ODI, EIAS & ICEI c/o DRN, leading company: Headquarters Via Ippolito Nievo 62 November 2010 00153 Rome, Italy Tel: +39-06-581-6074 Fax: +39-06-581-6390 This report has been prepared by the consortium DRN, mail@drn•network.com ADE, Particip, DIE, ODI, EIAS & ICEI. Belgium office Square Eugène Plasky, 92 The opinions expressed in this document represent the 1030 Brussels, Belgium Tel: +32-2-732-4607 views of the authors, which are not necessarily shared Tel: +32-2-736-1663 by the European Commission or by the authorities of the Fax: +32-2-706-5442 [email protected] countries concerned. Evaluation of the European Commission‟s Co- operation with Maldives Country Level Evaluation The report consists of two volumes: VOLUME I: DRAFT FINAL REPORT VOLUME II: ANNEXES VOLUME I: DRAFT FINAL REPORT 0. -

Energy Supply and Demand

Technical Report Energy Supply and Demand Fund for Danish Consultancy Services Assessment of Least-cost, Sustainable Energy Resources Maldives Project INT/99/R11 – 02 MDV 1180 April 2003 Submitted by: In co-operation with: GasCon Project ref. no. INT/03/R11-02MDV 1180 Assessment of Least-cost, Sustainable Energy Resources, Maldives Supply and Demand Report Map of Location Energy Consulting Network ApS * DTI * Tech-wise A/S * GasCon ApS Page 2 Date: 04-05-2004 File: C:\Documents and Settings\Morten Stobbe\Dokumenter\Energy Consulting Network\Løbende sager\1019-0303 Maldiverne, Renewable Energy\Rapporter\Hybrid system report\RE Maldives - Demand survey Report final.doc Project ref. no. INT/03/R11-02MDV 1180 Assessment of Least-cost, Sustainable Energy Resources, Maldives Supply and Demand Report List of Abbreviations Abbreviation Full Meaning CDM Clean Development Mechanism CEN European Standardisation Body CHP Combined Heat and Power CO2 Carbon Dioxide (one of the so-called “green house gases”) COP Conference of the Parties to the Framework Convention of Climate Change DEA Danish Energy Authority DK Denmark ECN Energy Consulting Network elec Electricity EU European Union EUR Euro FCB Fluidised Bed Combustion GDP Gross Domestic Product GHG Green house gas (principally CO2) HFO Heavy Fuel Oil IPP Independent Power Producer JI Joint Implementation Mt Million ton Mtoe Million ton oil equivalents MCST Ministry of Communication, Science and Technology MOAA Ministry of Atoll Administration MFT Ministry of Finance and Treasury MPND Ministry of National Planning and Development NCM Nordic Council of Ministers NGO Non-governmental organization PIN Project Identification Note PPP Public Private Partnership PDD Project Development Document PSC Project Steering Committee QA Quality Assurance R&D Research and Development RES Renewable Energy Sources STO State Trade Organisation STELCO State Electric Company Ltd. -

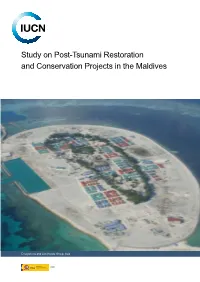

Study on Post-Tsunami Restoration and Conservation Projects in the Maldives

Study on Post-Tsunami Restoration and Conservation Projects in the Maldives Ecosystems and Livelihoods Group, Asia Study on Post-Tsunami Restoration and Conservation Projects in the Maldives Marie Saleem and Shahaama A. Sattar February 2009. Cover photo: Thaa Vilufushi after reclamation © Hissan Hassan Table of Contents 1 Introduction ................................................................................................... 3 2 Summary of post-tsunami restoration and conservation initiatives ............... 7 3 ARC/CRC Waste Management Programme .............................................. 11 3.1 Background ......................................................................................... 11 3.2 Summaries of outcomes in the Atolls .................................................. 12 3.2.1 Ari Atoll ......................................................................................... 13 3.2.2 Baa Atoll ....................................................................................... 13 3.2.3 Dhaalu Atoll .................................................................................. 13 3.2.4 Gaaf Alifu and Gaaf Dhaalu Atolls ................................................ 14 3.2.5 Haa Alifu Atoll............................................................................... 14 3.2.6 Haa Dhaalu Atoll .......................................................................... 15 3.2.7 Kaafu and Vaavu Atolls ................................................................ 15 3.2.8 Laamu Atoll .................................................................................