Good Housekeeping Mailing List Page 1 of 2 Case 1:15-Cv-09279-AT-JLC Document 1-1 Filed 11/24/15 Page 2 of 3

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Entertainment & Syndication Fitch Group Hearst Health Hearst Television Magazines Newspapers Ventures Real Estate & O

hearst properties WPBF-TV, West Palm Beach, FL SPAIN Friendswood Journal (TX) WYFF-TV, Greenville/Spartanburg, SC Hardin County News (TX) entertainment Hearst España, S.L. KOCO-TV, Oklahoma City, OK Herald Review (MI) & syndication WVTM-TV, Birmingham, AL Humble Observer (TX) WGAL-TV, Lancaster/Harrisburg, PA SWITZERLAND Jasper Newsboy (TX) CABLE TELEVISION NETWORKS & SERVICES KOAT-TV, Albuquerque, NM Hearst Digital SA Kingwood Observer (TX) WXII-TV, Greensboro/High Point/ La Voz de Houston (TX) A+E Networks Winston-Salem, NC TAIWAN Lake Houston Observer (TX) (including A&E, HISTORY, Lifetime, LMN WCWG-TV, Greensboro/High Point/ Local First (NY) & FYI—50% owned by Hearst) Winston-Salem, NC Hearst Magazines Taiwan Local Values (NY) Canal Cosmopolitan Iberia, S.L. WLKY-TV, Louisville, KY Magnolia Potpourri (TX) Cosmopolitan Television WDSU-TV, New Orleans, LA UNITED KINGDOM Memorial Examiner (TX) Canada Company KCCI-TV, Des Moines, IA Handbag.com Limited Milford-Orange Bulletin (CT) (46% owned by Hearst) KETV, Omaha, NE Muleshoe Journal (TX) ESPN, Inc. Hearst UK Limited WMTW-TV, Portland/Auburn, ME The National Magazine Company Limited New Canaan Advertiser (CT) (20% owned by Hearst) WPXT-TV, Portland/Auburn, ME New Canaan News (CT) VICE Media WJCL-TV, Savannah, GA News Advocate (TX) HEARST MAGAZINES UK (A+E Networks is a 17.8% investor in VICE) WAPT-TV, Jackson, MS Northeast Herald (TX) VICELAND WPTZ-TV, Burlington, VT/Plattsburgh, NY Best Pasadena Citizen (TX) (A+E Networks is a 50.1% investor in VICELAND) WNNE-TV, Burlington, VT/Plattsburgh, -

Margaret Cousins

Margaret Cousins: An Inventory of Her Papers at the Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center Descriptive Summary Creator Cousins, Margaret, 1905- Title Margaret Cousins Papers Dates: 1921-73 Extent 35 boxes (14.5 linear feet) Abstract: The papers of Texas writer and editor Margaret Cousins include correspondence and manuscripts reflecting her career, particularly as contributor to women's magazines, as editor of Lyndon Johnson's memoir, and as senior editor at Doubleday Publishing Company. RLIN Record # TXRC91-A12 Language English. Access Open for Research Administrative Information Acquisition Gift, 1973 Processed by Donald Firsching, Kendra Trachta, Miriam Wilde, 1990. Repository: Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center, University of Texas at Austin Cousins, Margaret, 1905- Biographical Sketch Born in Munday, Knox County, Texas, on January 26, 1905, Margaret Cousins was the first child of Walter Henry and Sue Margaret Reeves Cousins. Largely through the influence of her father, Margaret displayed an interest in pursuing a literary career at a young age. Upon graduating from Bryan Street High School in Dallas, Texas, in 1922, Cousins entered the University of Texas at Austin with a major in English literature. When Cousins left the university in 1926, she found employment as an apprentice on her father's Southern Pharmaceutical Journal in Dallas, advancing to associate editor in 1930 and editor in 1935. Cousins moved to New York City in 1937 to work as assistant editor of the Pictorial Review. When the Pictorial Review ceased publication in 1939, she began work as a copy writer in the promotional department of Hearst Magazines, Inc. Over the next few years she read manuscripts on a free-lance basis and wrote fashion captions for Heart's Good Housekeeping, to which she had been a contributor as early as 1930, when her poem “Indian Summer” appeared in the November issue. -

Good Housekeeping

Good Housekeeping CM405 - Group B Carly Boxer, Qing Li, Yilun Gu, Shunsuke Rachi The Magazine ● Class: Home Service & Home ● Profile: Print and digital publication, focuses on food, nutrition, fashion , beauty, relationships, home decorating and home care, health and child care and consumer and social issues. ● History 1st Edition published On May 2, 1885 by Clark W. Bryan Hearst bought Good Housekeeping in 1911 ● Publishing company Hearst Corporation ● Position: Symbol of consumer protection and quality assurance ● Field served: Her, Her Family, and Her Home Brief Introduction Some Numbers... 1. Circulation Total Circulation: 4,396,795 2. Cost per issue Monthly print + digital $2.50 per magazine 3. Annual subscription rate Monthly print + digital $21.97 annual fee Total Paid & Verified Subscriptions 4,057,525 92.3% 4. Circulation by geography Hearst One of the nation’s largest diversified media and information companies Started the business in 1887 Founder: William Randolph Hearst “Great content drives distribution, advertising and customers.” CONTENT CREATIVITY CONNECTION Hearst Daily 15 Newspaper 100+ Weekly Magazines 34Newspaper Around the world #2 US Magazine Publisher 29 28 14 150 TV Stations Websites Mobile sites Apps Audience (000) Readers Per Copy Median Age Median Household Income Adult Men Women Adult Men Women Adult Men Women Adult Men Women 19,032 1,975 17,057 4.45 0.46 3.99 55.6 57.4 55.4 $63,161 $62,246 $63,272 Reader Demographics Good Housekeeping is read by nearly one out of five American women each month. ● Women age 54.8 ● $61,694 income ● Home owners ● Graduated college ● Employed ● Married Advertisers For HER Beauty Clothing Sanitary For HER FAMILY For HER HOME Food Supermarket Seasoning Furniture Medicine Sanitizer Electronics Textile Our Competitor -- BHG 1. -

HEARST PROPERTIES HUNGARY HEARST MAGAZINES UK Hearst Central Kft

HEARST PROPERTIES HUNGARY HEARST MAGAZINES UK Hearst Central Kft. (50% owned by Hearst) All About Soap ITALY Best Cosmopolitan NEWSPAPERS MAGAZINES Hearst Magazines Italia S.p.A. Country Living Albany Times Union (NY) H.M.C. Italia S.r.l. (49% owned by Hearst) Car and Driver ELLE Beaumont Enterprise (TX) Cosmopolitan JAPAN ELLE Decoration Connecticut Post (CT) Country Living Hearst Fujingaho Co., Ltd. Esquire Edwardsville Intelligencer (IL) Dr. Oz THE GOOD LIFE Greenwich Time (CT) KOREA Good Housekeeping ELLE Houston Chronicle (TX) Hearst JoongAng Y.H. (49.9% owned by Hearst) Harper’s BAZAAR ELLE DECOR House Beautiful Huron Daily Tribune (MI) MEXICO Laredo Morning Times (TX) Esquire Inside Soap Hearst Expansion S. de R.L. de C.V. Midland Daily News (MI) Food Network Magazine Men’s Health (50.1% owned by Hearst UK) (51% owned by Hearst) Midland Reporter-Telegram (TX) Good Housekeeping Prima Plainview Daily Herald (TX) Harper’s BAZAAR NETHERLANDS Real People San Antonio Express-News (TX) HGTV Magazine Hearst Magazines Netherlands B.V. Red San Francisco Chronicle (CA) House Beautiful Reveal The Advocate, Stamford (CT) NIGERIA Marie Claire Runner’s World (50.1% owned by Hearst UK) The News-Times, Danbury (CT) HMI Africa, LLC O, The Oprah Magazine Town & Country WEBSITES Popular Mechanics NORWAY Triathlete’s World Seattlepi.com Redbook HMI Digital, LLC (50.1% owned by Hearst UK) Road & Track POLAND Women’s Health WEEKLY NEWSPAPERS Seventeen Advertiser North (NY) Hearst-Marquard Publishing Sp.z.o.o. (50.1% owned by Hearst UK) Town & Country Advertiser South (NY) (50% owned by Hearst) VERANDA MAGAZINE DISTRIBUTION Ballston Spa/Malta Pennysaver (NY) Woman’s Day RUSSIA Condé Nast and National Magazine Canyon News (TX) OOO “Fashion Press” (50% owned by Hearst) Distributors Ltd. -

2020 Genesis G70 Collects Good Housekeeping Award for Second Consecutive Year

2020 GENESIS G70 COLLECTS GOOD HOUSEKEEPING AWARD FOR SECOND CONSECUTIVE YEAR FOUNTAIN VALLEY, Calif., April 30, 2020 – Genesis today announced that its entry-luxury G70 was recognized as Good Housekeeping magazine’s 2020 Best New Family Car Award Winner in the Luxury Sedan category. This accolade represents the 21st award from a major, well- respected third-party since the G70’s launch in the Fall of 2018. “The G70 is the spark in our lineup. It’s the spring in our step,” said Mark Del Rosso, President and CEO of Genesis Motor North America. “So we just love it when third parties like Good Housekeeping get to experience the same feeling and share that with their audience.” “It’s a super fun-to-drive, upscale vehicle…,” wrote Good Housekeeping editors. “The exterior is designed to get noticed – and if you get behind the wheel, you’ll notice it does turn heads.” As the first Genesis model in the highly competitive entry-luxury sedan segment, G70 outperforms legacy luxury sport sedans with driver-focused performance. Since its debut, the G70 has been named the 2019 North American Car of the Year, the MotorTrend 2019 Car of the Year, as well as a category winner in the Car and Driver 2019 10Best awards, among more than a dozen other significant third-party industry awards. G70’s ability to acquire such a wide array of prominent industry awards is proof it resets benchmarks and expectations among luxury sport sedans, with the holistic integration of performance, refined luxury, aerodynamic design and an extensive array of passive and active safety equipment available. -

2013 Syndicate Directory

2013 Syndicate Directory NEW FEATURES CUSTOM SERVICES EDITORIAL COMICS POLITICAL CARTOONS What’s New in 2013 by Norman Feuti Meet Gil. He’s a bit of an underdog. He’s a little on the chubby side. He doesn’t have the newest toys or live in a fancy house. His parents are split up – his single mother supports them with her factory job income and his father isn’t around as often as a father ought to be. Gil is a realistic and funny look at life through the eyes of a young boy growing up under circumstances that are familiar to millions of American families. And cartoonist Norm Feuti expertly crafts Gil’s world in a way that gives us all a good chuckle. D&S From the masterminds behind Mobilewalla, the search, discovery and analytics engine for mobile apps, comes a syndicated weekly column offering readers both ratings and descriptions of highly ranked, similarly themed apps. Each week, news subscribers receive a column titled “Fastest Moving Apps of the Week,” which is the weekly hot list of the apps experiencing the most dramatic increases in popularity. Two additional “Weekly Category” features, pegged to relevant news, events, holidays and calendars, are also available. 3TW Drs. Oz and Roizen give readers quick access to practical advice on how to prevent and combat conditions that affect overall wellness and quality of life. Their robust editorial pack- age, which includes Daily Tips, a Weekly Feature and a Q & A column, covers a wide variety of topics, such as diet, exercise, weight loss, sleep and much more. -

Women's Magazines 1940-1960 Gender Roles and the Popular Press

THE BEDFORD SERIES IN HISTORY AND CULTURE Women's Magazines 1940-1960 Gender Roles and the Popular Press Edited with an Introduction by Nancy A. Walker Vanderbilt University Palgrave Macmillan For Bedford/St. Martin's History Editor: Katherine E. Kurzman Developmental Editor: Kate Sheehan Roach Production Editor: Stasia Zomkowski Marketing Manager: Charles Cavaliere Production Assistants: Melissa Cook, Beth Remmes Copyeditor: Barbara G. Flanagan Text Design: Claire Seng-Niemoeller Indexer: Steve Csipke Cover Design: Richard Emery Design, Inc. Cover Art: Women under hairdryers reading. UPI photo, 1961. UPI/Corbis-Bettmann. Composition: ComCom Printing and Binding: Haddon Craftsmen, Inc. President: Charles H. Christensen Editorial Director: Joan E. Feinberg Director ofEditing, Design, and Production: Marcia Cohen Managing Editor: Elizabeth M. Schaaf Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 97-74972 Copyright© 1998 by Bedford/St. Martin's All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted by any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, record ing, or otherwise, except as may be expressly pennitted by the applicable copyright statutes or in writing by the Publisher. Manufactured in the United States of America. 2 1 0 9 8 fedcba For information, write: Bedford/St. Martin's, 75 Arlington Street, Boston, MA 02116 (617-426-7440) ISBN: 978-0-312-10201-2 (paperback) ISBN 978-1-349-61484-3 ISBN 978-1-137-05068-7 (eBook) DOI 10. 1007/978-1-137-05068-7 Acknowledgments Figure 1. KLEENEX® and DELSEY® Tissue Products are registered trademarks of and used with permission of the Kimberly-Clark Corporation. -

Courtship at Seventeen

Winner of the 2014 Valentine J. Belfiglio Paper Prize Courtship at Seventeen: The Construction of Dissenting Feminine and Masculine Roles from 1955-1965 by Aiesha McFadden In the mid-1940s, white middle-class teenage females began to garner attention as growing free agents with money to spend and boys to date. According to renowned U.S. publisher, Walter Annenberg, these were also the young women who would lead America in the postwar era as citizen wives and mothers. Thus, a concentrated focus to help them transform from a girl to a woman began to take shape. In 1944, Annenberg launched Seventeen, a magazine geared towards young women aged 13 to 19, to address the economic, and more importantly in terms of this study, the sociocultural ideals and expectations of this demographic. Providing “sensible,” “wholesome,” and friendly advice to young girls on fashion, beauty, popular culture, and love, Seventeen immediately became the “bible” of the teen magazine genre by selling 94% of all copies published in its first year, 1 million after the first 16 months, and more than 2.5 million by July 1949.1 According to Seventeen’s promoters, friends and family shared copies with each other, ensuring that the magazine reached over half of the six million teenage girls in the United States.2 Thus, Seventeen was ideally 1 Kelley Massoni, “Bringing up ‘Baby:’ The Birth and Early Development of Seventeen Magazine” (PhD. dissertation, Wichita State University, 1999), 48 - 49. Seventeen was part of a portfolio of magazines and newspapers published by Annenberg’s Triangle Publications, Inc. 2 Although many different cultural groups comprised teenagers, the focus of this research is on white middle-class teenagers because this was the target demographic of Seventeen during the time period being studied. -

Presentation Outline 1. 2015 Economic Impact Study Results 2

Presentation Outline 1. 2015 Economic Impact Study Results 2. 2015 Event and Marketing Recap 3. 2016 Budget Review and Request Sugar Land Wine & Food Affair Economic Impact Study Results • $586,531 – Estimated Overall Economic Impact Category Estimated Economic Impact Food Sales $146,633 Shopping $129,037 Entertainment $193,555 Transportation $35,192 Hotel Spending $82,114 TOTAL $586,531 Sugar Land Wine & Food Affair Economic Impact Study Key Findings • Overnight Stays • Demographics Gender Income Age Male 36% Under $25,000 3% 18-24 8% Female 64% $25,000 - $49,999 7% 25-34 25% $50,000 - $74,999 19% 35-44 22% $75,000 - $100,00 23% 45-54 23% $100,000 + 48% 55-64 16% 65 + 6% Sugar Land Wine & Food Affair Looking Ahead… • Visit Sugar Land Brand – Social Media and Online Partnership – VSL Logo Visibility – VSL “Welcome” presence opportunity 2015 HIGHLIGHTS THE NUMBERS 30K 5,260 BITES TASTED BEERS POURED 505 WINES ATTENDANCE ATTENDANCE CONT. AS SEEN ON 365 Things to Do in EntertainmentNutz Houstoniamag.com Houston eWallstreeter Jewish Herald Voice Austin Food Magazine examiner.com localwineevents CarissaRaman.com FoodReference.com KHOU CBS Radio Fort Bend Independent KTRK Chron.com Fort Bend Lifestyles & Homes Mix 96.5 Community Impact News Fort Bend Star My Table Magazine CultureMap Houston FOX 26 Prime Living Magazine Daily Meal GHCVB Society Diaries Dailynews724 Good Taste with Tanji Sugar Land Sun Dallas Modern Luxury Guidry News Service Online Thrillist DallasNews.com Hank on Food visithoustontexas.com Eater Houston Houston Chronicle Wandering Educators Eating Our Words Houston Lifestyles & Homes YourFortBendNews Edible Austin Houston Newcomer Guides YourHoustonNews Edible Dallas Houston Press WEB & SOCIAL COVERAGE WEB & SOCIAL COVERAGE CONT. -

THE BIRTH and EARLY DEVELOPMENT of SEVENTEEN MAGAZINE by Copyright 2007 Kelley Massoni MA, Wichita State U

BRINGING UP ABABY@: THE BIRTH AND EARLY DEVELOPMENT OF SEVENTEEN MAGAZINE by Copyright 2007 Kelley Massoni M.A., Wichita State University, 1999 Submitted to the graduate degree program in Sociology and the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Kansas In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy _________________________________ Joey Sprague, Chair _________________________________ Robert J. Antonio _________________________________ William G. Staples _________________________________ Carol A. B. Warren _________________________________ Sherrie Tucker, American Studies Date Defended: ___________________ The Dissertation Committee for Kelley Massoni certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: BRINGING UP “BABY”: THE BIRTH AND EARLY DEVELOPMENT OF SEVENTEEN MAGAZINE _______________________________ Joey Sprague, Chair _________________________________ Robert J. Antonio _________________________________ William G. Staples _________________________________ Carol A. B. Warren _________________________________ Sherrie Tucker Date approved_____________________ ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Very much like my dissertation subjects, Helen Valentine and Seventeen, this project began as my conceptual creation and grew to become my own “baby.” However, again as with Helen and Seventeen, it took a village to raise this baby, and I am grateful and indebted to the people who assisted in this process. First and foremost, I must thank my dissertation committee members. Joey Sprague, my dissertation chair, “baby’s” godmother, and editor extraordinaire, helped me distill and analyze a sometimes overwhelming motherlode of data riches. As with the very best labor coaches, she knew when to cajole, to push, to soothe – and when to just leave me be. Many thanks to Bob Antonio, for having such faith in this project, offering helpful guidance along the way, and talking me off the occasional ledge. -

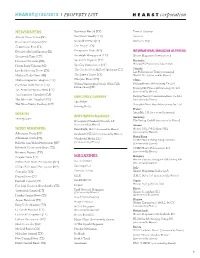

Hearst@125/2012 Property List

HEARST@125/2012 x PROPERTY LIST NEWSPAPERS Northeast Herald (TX) Town & Country Albany Times Union (NY) Northwest Weekly (TX) Veranda Beaumont Enterprise (TX) Norwalk Citizen (CT) Woman’s Day Connecticut Post (CT) Our People (TX) Edwardsville Intelligencer (IL) Pennysaver News (NY) INTERNATIONAL MAGAZINE ACTIVITIES Greenwich Time (CT) Randolph Wingspread (TX) Hearst Magazines International Houston Chronicle (TX) Southside Reporter (TX) Australia Hearst/ACP (50% owned by Hearst) Huron Daily Tribune (MI) Spa City Moneysaver (NY) The Greater New Milford Spectrum (CT) Canada Laredo Morning Times (TX) Les Publications Transcontinental Midland Daily News (MI) The Zapata Times (TX) Hearst Inc. (49% owned by Hearst) Midland Reporter-Telegram (TX) Westport News (CT) China Beijing Hearst Advertising Co. Ltd. Plainview Daily Herald (TX) Wilton/Gansevoort/South Glens Falls Moneysaver (NY) Beijing MC Hearst Advertising Co. Ltd. San Antonio Express-News (TX) (49% owned by Hearst) San Francisco Chronicle (CA) DIRECTORIES COMPANY Beijing Trends Communications Co. Ltd. The Advocate, Stamford (CT) (20% owned by Hearst) LocalEdge The News-Times, Danbury (CT) Shanghai Next Idea Advertising Co., Ltd. Metrix4Media France WEBSITES Inter-Edi, S.A. (50% owned by Hearst) INVESTMENTS/ALLIANCES Seattlepi.com Germany Newspaper National Network, LP Elle Verlag GmbH (50% owned by Hearst) (5.75% owned by Hearst) Greece WEEKLY NEWSPAPERS NewsRight, LLC (7.2% owned by Hearst) Hearst DOL Publishing S.R.L. (50% owned by Hearst) Advertiser North (NY) quadrantONE, LLC (25% owned by Hearst) Advertiser South (NY) Hong Kong Wanderful Media, LLC SCMP Hearst Hong Kong Limited (12.5% owned by Hearst) Ballston Spa/Malta Pennysaver (NY) (30% owned by Hearst) Bulverde Community News (TX) SCMP Hearst Publications Ltd. -

Cathie Black, President of Hearst Magazines, Sees a Bright Future for a Much- Misunderstood Medium

Leadership Interview “We had a choice. We could sit back and let the negative discussion of our industry take its course, or we could take action.” Despite one of the toughest periods in history for the magazine industry, Cathie Black, president of Hearst Magazines, sees a bright future for a much- misunderstood medium. Talking to THE FOCUS, she describes how her company came through the economic storm and how resilience can be about sticking to your convictions. Photos: Jürgen Frank 6 THE FOCUS VOL. XIV/1 Leadership Interview the Focus: According to Hearst Corporation’s 2009 Annual Review, the strategy for coping with the recent recession turned on innovation, a path that has been fol- lowed by some of the world’s most successful compa- nies during tough economic times. To what extent was innovation responsible for Hearst’s resilience? Cathie Black: Hearst has always been innovative. When the advent of television hurt the pillar of the company, its newspaper operations, Hearst expanded into maga- zines and television. The company got into cable when it was first emerging decades ago. Today we’re in inter- active media and about 200 other businesses. Within the magazine division, we’ve really pushed technology, we’ve pushed efficiency, and – in terms of being resil- the hearst CorPoratIon ient – we always have a couple of prospective magazine From newspapers to new media ideas in the petri dish that are being considered. on March 4, 1887, a young man named William the Focus: During the downturn you launched a new randolph hearst first placed his name on the publication, Food Network Magazine.