The Causes of the English Civil

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Politics of Liberty in England and Revolutionary America

P1: IwX/KaD 0521827450agg.xml CY395B/Ward 0 521 82745 0 May 7, 2004 7:37 The Politics of Liberty in England and Revolutionary America LEE WARD Campion College University of Regina iii P1: IwX/KaD 0521827450agg.xml CY395B/Ward 0 521 82745 0 May 7, 2004 7:37 published by the press syndicate of the university of cambridge The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge, United Kingdom cambridge university press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge cb2 2ru, uk 40 West 20th Street, New York, ny 10011-4211, usa 477 Williamstown Road, Port Melbourne, vic 3207, Australia Ruiz de Alarcon´ 13, 28014 Madrid, Spain Dock House, The Waterfront, Cape Town 8001, South Africa http://www.cambridge.org C Lee Ward 2004 This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published 2004 Printed in the United States of America Typeface Sabon 10/12 pt. System LATEX 2ε [tb] A catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Ward, Lee, 1970– The politics of liberty in England and revolutionary America / Lee Ward p. cm. Includes bibliographical references (p. ) and index. isbn 0-521-82745-0 1. Political science – Great Britain – Philosophy – History – 17th century. 2. Political science – Great Britain – Philosophy – History – 18th century. 3. Political science – United States – Philosophy – History – 17th century. 4. Political science – United States – Philosophy – History – 18th century. 5. United States – History – Revolution, 1775–1783 – Causes. -

I. History and Ideology in the English Revolution1

THE HISTORICAL JOURNAL VOL. VIII 1965 No. 2 I. HISTORY AND IDEOLOGY IN THE ENGLISH REVOLUTION1 By QUENTIN SKINNER Christ's College, Cambridge IDEOLOGICAL arguments are commonly sustained by an appeal to the past, an appeal either to see precedents in history for new claims being advanced, or to see history itself as a development towards the point of view being advocated or denounced.2 Perhaps the most influential example from English history of this prescriptive use of historical information is provided by the ideological arguments associated with the constitutional revolution of the seventeenth century. It was from a propagandist version of early English history that the 'whig' ideology associated with the Parliamentarians—the ideology of customary law, regulated monarchy and immemorial Parliamen- tary right—drew its main evidence and strength. The process by which this 'whig' interpretation of history became bequeathed to the eighteenth century as accepted ideology has of course already been definitively labelled by Professor Butterfield, and described in his book on The Englishman and his History.3 It still remains, however, to analyse fully the various other ways in which awareness of the past became a politically relevant factor in English society during its constitutional upheavals. The acceptance of the ' whig' view of early English history in fact represented only the triumph of one among several conflictinb ideologies which had relied on identical historical backing to their claims. And despite the resolution of this conflict by universal acceptance of the ' whig' view, the ' whigs' themselves were nevertheless to be covertly influenced by the rival ideologies which their triumph might seem to have suppressed. -

Social-Property Relations, Class-Conflict and The

Historical Materialism 19.4 (2011) 129–168 brill.nl/hima Social-Property Relations, Class-Conflict and the Origins of the US Civil War: Towards a New Social Interpretation* Charles Post City University of New York [email protected] Abstract The origins of the US Civil War have long been a central topic of debate among historians, both Marxist and non-Marxist. John Ashworth’s Slavery, Capitalism, and Politics in the Antebellum Republic is a major Marxian contribution to a social interpretation of the US Civil War. However, Ashworth’s claim that the War was the result of sharpening political and ideological – but not social and economic – contradictions and conflicts between slavery and capitalism rests on problematic claims about the rôle of slave-resistance in the dynamics of plantation-slavery, the attitude of Northern manufacturers, artisans, professionals and farmers toward wage-labour, and economic restructuring in the 1840s and 1850s. An alternative social explanation of the US Civil War, rooted in an analysis of the specific path to capitalist social-property relations in the US, locates the War in the growing contradiction between the social requirements of the expanded reproduction of slavery and capitalism in the two decades before the War. Keywords origins of capitalism, US Civil War, bourgeois revolutions, plantation-slavery, agrarian petty- commodity production, independent-household production, merchant-capital, industrial capital The Civil War in the United States has been a major topic of historical debate for almost over 150 years. Three factors have fuelled scholarly fascination with the causes and consequences of the War. First, the Civil War ‘cuts a bloody gash across the whole record’ of ‘the American . -

Cromwelliana 2012

CROMWELLIANA 2012 Series III No 1 Editor: Dr Maxine Forshaw CONTENTS Editor’s Note 2 Cromwell Day 2011: Oliver Cromwell – A Scottish Perspective 3 By Dr Laura A M Stewart Farmer Oliver? The Cultivation of Cromwell’s Image During 18 the Protectorate By Dr Patrick Little Oliver Cromwell and the Underground Opposition to Bishop 32 Wren of Ely By Dr Andrew Barclay From Civilian to Soldier: Recalling Cromwell in Cambridge, 44 1642 By Dr Sue L Sadler ‘Dear Robin’: The Correspondence of Oliver Cromwell and 61 Robert Hammond By Dr Miranda Malins Mrs S C Lomas: Cromwellian Editor 79 By Dr David L Smith Cromwellian Britain XXIV : Frome, Somerset 95 By Jane A Mills Book Reviews 104 By Dr Patrick Little and Prof Ivan Roots Bibliography of Books 110 By Dr Patrick Little Bibliography of Journals 111 By Prof Peter Gaunt ISBN 0-905729-24-2 EDITOR’S NOTE 2011 was the 360th anniversary of the Battle of Worcester and was marked by Laura Stewart’s address to the Association on Cromwell Day with her paper on ‘Oliver Cromwell: a Scottish Perspective’. ‘Risen from Obscurity – Cromwell’s Early Life’ was the subject of the study day in Huntingdon in October 2011 and three papers connected with the day are included here. Reflecting this subject, the cover illustration is the picture ‘Cromwell on his Farm’ by Ford Madox Brown (1821–1893), painted in 1874, and reproduced here courtesy of National Museums Liverpool. The painting can be found in the Lady Lever Art Gallery in Port Sunlight Village, Wirral, Cheshire. In this edition of Cromwelliana, it should be noted that the bibliography of journal articles covers the period spring 2009 to spring 2012, addressing gaps in the past couple of years. -

French Revolution and English Revolution Comparison Chart Print Out

Socials 9 Name: Camilla Mancia Comparison of the English Revolution and French Revolution TOPIC ENGLISH REVOLUTION FRENCH REVOLUTION SIMILARITIES DIFFERENCES 1625-1689 Kings - Absolute monarchs - Absolute monarchs - Kings ruled as Absolute - English Kings believed in Divine - James I: intelligent; slovenly - Louis XIV: known as the “Sun King”; Monarchs Right of Kings and French did habits; “wisest fool in saw himself as center of France and - Raised foreign armies not Christendom”; didn’t make a forced nobles to live with him; - Charles I and Louis XVI both - Charles I did not care to be good impression on his new extravagant lifestyle; built Palace of did not like working with loved whereas Louis XVI initially subjects; introduced the Divine Versailles ($$) Parliament/Estates General wanted to be loved by his people Right Kings - Louis XV: great grandson of Louis XIV; - Citizens did not like the wives of - Charles I did not kill people who - Charles I: Believed in Divine only five years old when he became Charles I (Catholic) and Louis were against him (he Right of Kings; unwilling to King; continued extravagances of the XVI (from Austria) imprisoned or fined them) compromise with Parliament; court and failure of government to - Both Charles I and Louis XVI whereas Louis XVI did narrow minded and aloof; lived reform led France towards disaster punished critics of government - Charles I called Lord Strafford, an extravagant life; Wife - Louis XVI; originally wanted to be Archbishop Laud and Henrietta Maria and people loved; not interested -

The English Civil Wars a Beginner’S Guide

The English Civil Wars A Beginner’s Guide Patrick Little A Oneworld Paperback Original Published in North America, Great Britain and Australia by Oneworld Publications, 2014 Copyright © Patrick Little 2014 The moral right of Patrick Little to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted by him/her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 All rights reserved Copyright under Berne Convention A CIP record for this title is available from the British Library ISBN 9781780743318 eISBN 9781780743325 Typeset by Siliconchips Services Ltd, UK Printed and bound in Denmark by Nørhaven A/S Oneworld Publications 10 Bloomsbury Street London WC1B 3SR England Stay up to date with the latest books, special offers, and exclusive content from Oneworld with our monthly newsletter Sign up on our website www.oneworld-publications.com Contents Preface vii Map of the English Civil Wars, 1642–51 ix 1 The outbreak of war 1 2 ‘This war without an enemy’: the first civil war, 1642–6 17 3 The search for settlement, 1646–9 34 4 The commonwealth, 1649–51 48 5 The armies 66 6 The generals 82 7 Politics 98 8 Religion 113 9 War and society 126 10 Legacy 141 Timeline 150 Further reading 153 Index 157 Preface In writing this book, I had two primary aims. The first was to produce a concise, accessible account of the conflicts collectively known as the English Civil Wars. The second was to try to give the reader some idea of what it was like to live through that trau- matic episode. -

1 JAMES M. VAUGHN Department of History University Of

JAMES M. VAUGHN Department of History University of Texas at Austin 128 Inner Campus Dr. B7000 Austin, TX 78712-1739 EDUCATION Ph.D., Department of History, University of Chicago, Chicago, IL 2009 M.A., Division of the Social Sciences, University of Chicago, Chicago, IL 2004 B.A., Department of History, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY 2000 PROFESSIONAL APPOINTMENTS Assistant Professor, Department of History, University of Texas at Austin 2008 - present Assistant Director, Program in British Studies 2009 - present Jack Miller Research Fellow in Representative Institutions, the MacMillan 2011 - 2012 Center for International and Area Studies, Yale University, New Haven, CT PUBLICATIONS (including Accepted and In Press) Book Vaughn, J. M. (In production [copyediting], expected September 2018). The Politics of Empire at the Accession of George III: The East India Company and the Crisis and Transformation of Britain’s Imperial State. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. 130,000 words. Peer-Reviewed Journal Articles and Book Chapters Vaughn, J. M. (August 2017, published online as “ahead-of-print” featured article [DOI: 10.3366/brw.2017.0283]; in press, September 2018). John Company Armed: The English East India Company, the Anglo-Mughal War and Absolutist Imperialism, c. 1675-1690. Britain and the World, 11 (2). Austen, R. A., & Vaughn, J. M. (2011). The Territorialization of Empire: Social Imperialism and Britain’s Moves into India and Tropical Africa. In T. Falola and E. Brownell (Eds.), Africa, Empire and Globalization: Essays in Honor of A. G. Hopkins (193-212). Durham, NC: Carolina Academic Press. 1 Non-Peer Reviewed Articles Vaughn, J. M. (2013). 1776 in World History: The American Revolution as Bourgeois Revolution. -

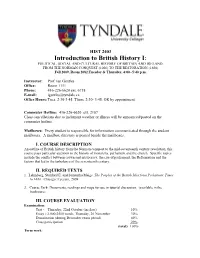

Introduction to British History I

HIST 2403 Introduction to British History I: POLITICAL, SOCIAL AND CULTURAL HISTORY OF BRITAIN AND IRELAND, FROM THE NORMAN CONQUEST (1066) TO THE RESTORATION (1660) Fall 2009, Room 2082,Tuesday & Thursday, 4:00--5:40 p.m. Instructor: Prof. Ian Gentles Office: Room 1111 Phone: 416-226-6620 ext. 6718 E-mail: [email protected] Office Hours: Tues. 2:30-3:45, Thurs. 2:30- 3:45, OR by appointment Commuter Hotline: 416-226-6620 ext. 2187 Class cancellations due to inclement weather or illness will be announced/posted on the commuter hotline. Mailboxes: Every student is responsible for information communicated through the student mailboxes. A mailbox directory is posted beside the mailboxes. I. COURSE DESCRIPTION An outline of British history from the Norman conquest to the mid-seventeenth century revolution, this course pays particular attention to the history of monarchy, parliament and the church. Specific topics include the conflict between crown and aristocracy, the rise of parliament, the Reformation and the factors that led to the turbulence of the seventeenth century. II. REQUIRED TEXTS 1. Lehmberg, Stanford E. and Samantha Meigs. The Peoples of the British Isles from Prehistoric Times to 1688 . Chicago: Lyceum, 2009 2. Course Pack: Documents, readings and maps for use in tutorial discussion. (available in the bookstore) III. COURSE EVALUATION Examination : Test - Thursday, 22nd October (in class) 10% Essay - 2,000-2500 words, Thursday, 26 November 30% Examination (during December exam period) 40% Class participation 20% (total) 100% Term work : a. You are expected to attend the tutorials, preparing for them through the lectures and through assigned reading. -

Anglo-Saxons and English Identity

Masaryk University Faculty of Arts Department of English and American Studies English Language and Literature Anna Šerbaumová Anglo-Saxons and English Identity Master’s Diploma Thesis Supervisor: Dr., M.A. Stephen Paul Hardy, Ph. D. 2010 I declare that I have worked on this thesis independently, using only the primary and secondary sources listed in the bibliography. V Plzni dne 22.11.2010 …………………………………………… I would like to thank my supervisor Dr., M.A. Stephen Paul Hardy, Ph.D. for his advice and comments, and my family and boyfriend for their constant support. Table of Contents 0 Introduction ............................................................................................................................ 1 1 Anglo-Saxon Period (410–1066) ........................................................................................... 4 1.1 Anglo-Saxon Settlement in Britain ................................................................................ 4 1.2 A Brief History of the Anglo-Saxon Period ................................................................... 5 1.3 ―Saxons‖,― English‖ or ―Anglo-Saxons‖? ..................................................................... 7 1.4 The Origins of English Identity and the Venerable Bede .............................................. 9 1.5 English Identity in the Ninth Century and Alfred the Great‘s Preface to the Pastoral Care ...................................................................................................... 15 1.6 Conclusion .................................................................................................................. -

STUART ENGLAND OVERVIEW HISTORY KNOWLEDGE ORGANISER 1603 – James I James I Was King of England and Scotland Following the Death of Elizabeth I

TIMELINE OF STUART ENGLAND OVERVIEW HISTORY KNOWLEDGE ORGANISER 1603 – James I James I was king of England and Scotland following the death of Elizabeth I. The period ended with the death of Queen Anne who was YEAR 8 – TERM 2 1605 – Gunpowder Plot succeeded by the Hanoverian, George I from the House of Hanover. 1625 – Charles I James I was a Protestant and his reign is most famous for the 1603 – 1714: STUART ENGLAND Gunpowder Plot. His son, Charles I, led the country into Civil War and 1625 – Charles I married a Catholic, Henrietta Maria was executed in 1649. This was followed by the period known as the KEY INDIVIDUALS (other than Commonwealth, where there was no monarch ruling the country. Monarchs – above) 1628 – Charles collected tax without Parliament’s permission Instead, Oliver Cromwell was Lord Protector and famously banned 1629 – Charles dissolved Parliament (until 1640) Christmas. The Restoration saw the Stuarts returned to the throne Samuel Pepys Henrietta Maria under the ‘Merry Monarch’ Charles II. This period is best known for the 1634 – Ship money collected Great Plague and the Great Fire of London. In 1688 powerful Archbishop Laud Robert Cecil 1637 – Scots rebelled against new Prayer Book and Archbishop Protestants in England overthrew James II and replaced him with his Guy Fawkes Oliver Cromwell daughter and son-in-law, William and Mary of Orange, in the ‘Glorious Laud cut Puritans’ ears off Revolution. The final Stuart, Anne, had 17 pregnancies but left no heir. Nell Gwyn Buckingham 1640 – Parliament reopened but argued with the King KEY TERMS 1642 – Charles tried to arrest 5 MPs. -

The Glorious Revolution Reconsidered: Whig Historiography

Author: Omar El Sharkawy Title: “The Glorious Revolution Reconsidered: Whig Historiography and Revisionism in Historical and Intellectual Context” Source: Prandium: The Journal of Historical Studies, Vol. 9, No. 1 (Fall, 2020). Published by: The Department of Historical Studies, University of Toronto Mississauga Stable URL: https://jps.library.utoronto.ca/index.php/prandium/index The Glorious Revolution is the subject of extensive discussion in relation to the meaning and conduct of revolutionary behavior.1 There are several schools of thought on the Glorious Revolution, but this paper focuses on the most firmly entrenched “traditional” perspective. In its most pure form, the traditional or “Whig” interpretation was first articulated by Thomas B. Macaulay in the nineteenth century. He viewed the Glorious Revolution as a mostly staid and boring affair: a moderate political revolution guided by the propertied political classes that established constitutionalism, parliamentary sovereignty, and religious toleration as the bedrock of English government. This revolution displaced a tyrannical Catholic monarch, James II, who was bent on absolute power and religious persecution. The “Whig interpretation of history” has been a source of both praise and criticism in the revolution’s long and well-established historiographical tradition.2 Modern scholarly debates concerning the revolution have almost completely revised the Whig perspective as a moderate and quintessentially English revolution. However, the interpretation of the degree of social -

English Civil War to Restoration Key Concept: Narrative Account Topic Summary Chronological Events Should Be Sequenced in Your Writing in Chronological Order

Unit 3: The English Civil War to Restoration Key concept: Narrative Account Topic Summary Chronological Events should be sequenced in your writing in chronological order. Past tense Narratives should be written in the past tense e.g. the king was crowned in 1660. 1660 Charles II is 1605 The Gun- 1629 The 1640 Charles I crowned King, powder Plot start of the recalls Parliament 1648 Parliament 1653 Oliver Crom- beginning the Third person Narratives should be written in the third person . Do not use ‘I’; ‘we’; or ‘you’ almost destroys ‘eleven-years to pay for the wins the Second well becomes ‘Lord Restoration Parliament Bishops’ War tyranny’ Civil War Protector’ Linking Connections should be made between events, linking them together in a clear se- quence. Relevant detail Include relevant details for each event you are describing, including dates, names, etc. 1625 Charles I 1637 Archbishop 1642 The English 1648 Trial and exe- 1603 James I 1658 Death of becomes King Laud introduces Civil War breaks cution of Charles I; becomes King Oliver Cromwell of England of England his prayer book to out England declared a Scotland Commonwealth Key People Charles I The second Stuart king of England, execut- Archbishop Laud Famously introduced new prayer ed by Parliament in 1648 following the Civil War. books along with other religious changes that bought back some Catholic practices. Keywords John Pym Puritan member of Parliament, and a Oliver Cromwell Parliamentary general, who be- major opponent of Charles I before the Civil War. came Lord Protector of the Commonwealth in 1653 Absolutist A ruler who has supreme authority and power Long Parliament A parliament, which met, on and off, from 1640- 1660 General Monck A general who had worked with Charles II The king of England following the Resto- Bishops’ War An uprising against Charles I’s religious reforms which Newcastle Propositions A series of Parliament’s demands in 1646, Charles I and Cromwell who dismissed Parliament ration.