Papers BMJ: First Published As 10.1136/Bmj.324.7344.1006 on 27 April 2002

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Roman York: from the Core to the Periphery

PROCEEDINGS OF THE WORLD CLASS HERITAGE CONFERENCE, 2011 Sponsored by York Archaeological Forum Roman York, from the Core to the Periphery: an Introduction to the Big Picture Patrick Ottaway PJO Archaeology Introduction Amongst the objectives of the 2012 World Class Heritage conference was a review of some of the principal research themes in York’s archaeology in terms both of what had been achieved since the publication of the York Development and Archaeology Study in 1991 (the ‘Ove Arup Report’) and of what might be achieved in years to come. As far as the Roman period is concerned, one of the more important developments of the last twenty years may be found in the new opportunities for research into the relationship between, on the one hand, the fortress and principal civilian settlements, north-east and south-west of the Ouse, - ‘the core’ – and, on the other hand, the surrounding region, in particular a hinterland zone within c. 3-4 km of the city centre, roughly between the inner and outer ring roads – ‘the periphery’. This development represents one of the more successful outcomes from the list of recommended projects in the Ove Arup report, amongst which was ‘The Hinterland Survey’ (Project 7, p.33). Furthermore, it responds to the essay in the Technical Appendix to the Arup report in which Steve Roskams stresses that it is crucial to study York in its regional context if we are to understand it in relation to an ‘analysis of Roman imperialism’ (see also Roskams 1999). The use of the term ‘imperialism’ here gives a political edge to a historical process more often known as ‘Romanisation’ for which, in Britain, material culture is the principal evidence in respect of agriculture, religion, society, technology, the arts and so forth. -

Researching the Roman Collections of the Yorkshire Museum

Old Collections, New Questions: Researching the Roman Collections of the Yorkshire Museum Emily Tilley (ed.) 2018 Page 1 of 124 Contents Introduction .............................................................................................................. 5 1. Research Agenda .............................................................................................. 7 1.1. Introduction ..................................................................................................... 8 1.2. Previous Research Projects ............................................................................ 9 1.3. Potential ......................................................................................................... 10 1.4. Organisations ................................................................................................. 12 1.5. Themes .......................................................................................................... 15 2. An Overview of the Roman Collections ......................................................... 21 2.1. Introduction ................................................................................................... 22 2.2. Summary of Provenance ............................................................................... 24 2.3. The Artefacts: Introduction ........................................................................... 25 2.4. Stone Monuments and Sculpture ................................................................ 26 2.5. Construction Materials ................................................................................. -

Alfonso Mendoza

Alfonso Mendoza Department of Economics Tel: +44 1 904 433791 The University of York E-mail: [email protected] Heslington, York, UK Web Page: YO10 5DD http://www-users.york.ac.uk/~amv101 Education - PhD, Economics, The University of York, United Kingdom, Oct. 1999 to Sep. 2003. Thesis: Monetary Policy Analysis and Conditional Volatility Models in Emerging Markets. - MSc., Project Analysis & Investments, The University of York, United Kingdom, Sep. 1998–Sep 1999. Dissertation: Market Efficiency in the Mexican Foreign Exchange Market. - MSc., Finance, Mexico Autonomous Institute of Technology (ITAM), Jan. 1995- Dec. 1996. Dissertation: Asset Management and Hedging with Swaps: the case of Bank One Co. - Diploma, Short Course in Social Projects Appraisal, CEPEP-BANOBRAS, Mexico, 1998 - Diploma, Mexican Stock Exchange (BMV), Jun. 1993-Jun. 1994. - B.S., Economics, State of Mexico Autonomous University, Sep. 1988-Jun. 1993. Thesis: International Capital Mobility and Economic Policy Efficiency in Mexico, an application of the Mundell-Fleming model. Publications ____and Fountas and S. Karanasos, M. "Output Variability and Economic Growth: the Japanese Case", Bulletin of Economic Research, July 2004. ____and Domac, I. "On the Effectiveness of Foreign Exchange Interventions, Evidence from Mexico and Turkey in the Post Float Periods", Policy Research Working Paper, No. 3288, The World Bank, April 2004. ____"The Inflation-output Volatility Tradeoff and exchange rate shocks in Mexico and Turkey", Central Bank Review, Vol 3, No. 1, January 2003. Work in Progress - "Modeling Long Memory and Default Risk Contagion in Latin American Sovereign Bond Markets", presented at the Annual Meeting of the Monetary, Macro and Finance Research Group Conference, University of Cambridge, September 2003. -

Habitats Regulations Assessment Screening Report September 2019

Heslington Parish Neighbourhood Plan (Submission Version) Habitats Regulations Assessment Screening Report September 2019 Heslington Parish Neighbourhood Plan Habitats Regulation Screening Report CONTENTS 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................. 3 Legislative Basis .................................................................................................................................... 3 Planning Context .................................................................................................................................. 5 2. Methodology................................................................................................................ 7 Identifying European Sites and their qualifying features..................................................................... 7 Qualifying features of the identified European Sites and summary of impacts .................................. 9 Appraisal of Neighbourhood Plan ...................................................................................................... 14 3. Screening Assessment ................................................................................................ 15 Part 1 Assessment of the Heslington Parish Neighbourhood Plan.............................................. 15 Part 2 Cumulative effects of the Neighbourhood Plan ................................................................ 36 4. Consultation .............................................................................................................. -

Selby District Council LDF

Selby District Council LDF Core Strategy Submission Draft: Examination in Public, Pre- hearing Meeting, Highways Agency and North Yorkshire County Council (NYCC) (Local Highways Agency) Position Statement 1 Introduction 1.1 The Highways Agency and NYCC have been in consultation with Selby District Council for some three years and as a statutory consultee has commented on the various draft versions of the Council’s Core Strategy proposals and their draft proposed development sites allocations. 1.2 The Highways Agency and NYCC, as local highways authority, are committed to working in partnership with Selby District Council to ensure that development is implemented in a sustainable and timely manner without an adverse impact on the safe and efficient operation of both the strategic road network and the local road network. 2 Strategic Road Network and Local Road Network Description 2.1 Within Selby District there are three sections of the Strategic Road Network (SRN) managed by the Highways Agency on behalf of the Secretary of State for Transport. These are: • M62 • A1(M) • A64(T) 2.2 The M62 and A1(M) are three lane dual carriageway motorways with grade separated junctions. The A64(T) is an all-purpose two lane dual carriageway with grade separated junctions. 2.3 The local road network (LRN) within Selby District is managed by NYCC as the Local Highway Authority. Operational conditions 2.4 At present no sections of the SRN or LRN within Selby district have regular weekday traffic congestion problems. However, the A64(T) acts as a commuter route between York and the towns and villages beyond and the West Yorkshire urban centres, thus there is a predominant traffic flow in the westbound direction in the morning peak and eastbound in the evening peak. -

The Newsletter of the Roman Finds Group LUCERNA: the NEWSLETTER of the ROMAN FINDS GROUP ISSUE 51, JULY 2016

LUCERNA Issue 51 • July 2016 The Newsletter of The Roman Finds Group LUCERNA: THE NEWSLETTER OF THE ROMAN FINDS GROUP ISSUE 51, JULY 2016 Editorial Contents Welcome to Lucerna 51. RFG News and Notices 1 This edition kicks off with a couple of updates from our AGM that was held during the RFG Spring Conference Bone Spatulate Strips From Roman London 6 back in April and the revised list of RFG Committee Glynn J.C. Davis members. In doing so we would like to welcome our newest committee member, Barbara Birley - you can Ongoing Research: 13 read a bit more about Barbara, her work and what she Global Glass Adornments Event Horizon in the hopes to bring to the RFG below. Congratulations also Late Iron Age and Roman Period Frontiers goes to Marta Alberti who has received the first ever RFG (100 BC - AD 250) Grant that has helped her research on spindle whorls Tatiana Ivleva from Vindolanda. Furthermore, there’s all you need to know about who’s talking and how to book your place The Roman Finds Group 15 at the next RFG Autumn Conference at the University Spring Conference Reviews of Reading on the 9th and 10th September 2016. Don’t miss out: we look forward to seeing many of you there. Recent Publications 24 This issue also contains a couple of interesting research Conferences and Events 24 pieces. The first is by Glynn Davis who gives us an insightful account of the use and significance of polished bone spatulate strips in London. The second, by Tatiana Communications Secretary (and Website Manager): Ivleva, is an update about her ongoing research on the Nicola Hembrey production, distribution and function of glass bracelets [email protected] in Roman Britain. -

Maple Cottage, Main Street, Heslington, York YO10 5DX Guide Price £595,000

Maple Cottage, Main Street, Heslington, York YO10 5DX Guide Price £595,000 • Detached Character • Three Bedrooms • Bath and En-Suite Bungalow Shower Room • Large Dining Kitchen • Courtyard Garden. • Easy Access to York City Garages Centre Micklegate | 01904 650650 58 Micklegate, York, North Yorkshire, YO1 6LF A beautifully presented detached bungalow situated BEDROOM 1 within the highly sought after Heslington area of York. The property is positioned up a gravelled drive way, providing a very private setting. ENTRANCE HALL An oak entrance door with glazed insert gives access to the entrance hall. Oak flooring. Coving to the ceiling. Built-in tank cupboard and further built-in cloaks cupboard. SITTING ROOM A good sized double bedroom with sliding door to the side elevation. Built-in wardrobes. Coving to the ceiling. EN-SUITE SHOWER ROOM The focal point of the sitting room is a fireplace with timber mantel, stone insert and hearth housing a real flame gas fire. Coving to the ceiling. Double doors to the front elevation. DINING KITCHEN Separate fully tiled shower cubicle, pedestal wash basin and low flush WC. Shaver point and light. Chrome ladder style heated towel rail. Extractor fan. BEDROOM 2 A good sized room with a range of fitted wall and floor units with work surfaces incorporating a single drainer ceramic sink. Built-in NEFF microwave and oven. Five ring gas hob with extractor fan over. Built- in fridge freezer, wine cooler, washing machine and A further double bedroom with windows to the side dishwasher. Tiled splashbacks. Separate dining area and rear elevations. Coving to the ceiling. -

York Flood Inquiry

York Flood Inquiry 1 2 Foreword On Boxing Day 2015, the city of York experienced exceptional flooding. Readers of this Report will be familiar with photographs and footage of York showing abandoned properties, marooned cars, residents being rescued from their homes in boats and Chinook helicopters airlifting equipment to repair the Foss Barrier. The problems did not recede as quickly as the water, many people were unable to return home for months whilst their houses were being repaired and businesses were put out of action for months on end. Even now, York is working to return to normal. In April 2016, I was appointed by City of York Council (CYC) as Chair of its independent Inquiry into the Boxing Day floods. Technical flooding expertise has been provided by the appointed panel members, Tom Toole and Laurence Waterhouse. Mr. Toole has had an extensive career in the Water Industry and he retired in late 2010 from his role as Associate Director/Commercial Director for the Arup UK Water Business. In the latter years of his career his experience enabled him to act as an Independent Expert Witness on many water related disputes. Mr. Waterhouse is the Technical Director of Flood Risk and Climate Change at Consulting Engineers Pell Frischmann. He is a past Chairman of the National Flood Forum and a Member of the United Nations Expert Panel on Climate Change Adaptation. He has over 40 years’ experience as a chartered surveyor specialising in flood protection. Over the last seven months the Inquiry Panel has held public meetings, considered over 50 written submissions and sent out a questionnaire to flood affected residents and businesses. -

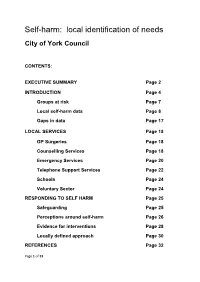

Self-Harm: Local Identification of Needs

Self-harm: local identification of needs City of York Council CONTENTS: EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Page 2 INTRODUCTION Page 4 Groups at risk Page 7 Local self-harm data Page 8 Gaps in data Page 17 LOCAL SERVICES Page 18 GP Surgeries Page 18 Counselling Services Page 18 Emergency Services Page 20 Telephone Support Services Page 22 Schools Page 24 Voluntary Sector Page 24 RESPONDING TO SELF HARM Page 25 Safeguarding Page 25 Perceptions around self-harm Page 26 Evidence for interventions Page 28 Locally defined approach Page 30 REFERENCES Page 32 Page 1 of 33 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Self-harm is reported to be a growing concern and issue locally. York does have slightly higher rates of hospital admissions due to self-harm than England average rates and anecdotal and audit information from a range of sources identifies growing concerns about increases in self- harm. There is a current gap in the availability of comprehensive and robust data to be able to clearly identify the full scope of the issue. There are inconsistent ways of recording, reporting and sharing self-harm related information about risk and prevalence where an incident does not result in a hospital admission. Where self-harming behaviour does result in a hospital admission, there is a good availability of local data but this does not provide a full picture about the scope of self-harm. A range of services and staff groups identify self-harm as a concern but information about the prevalence of this behaviour is not consistently collected or shared between services. There is a lack of readily available advice and information for people to access about self-harm, how to identify when self-harming behaviour may be happening, what to do and how to support someone who is self- harming. -

Heslington Village Design Statement HESLINGTON VILLAGE DESIGN STATEMENT

Heslington Village Design Statement HESLINGTON VILLAGE DESIGN STATEMENT INDEX 1 Introduction . 1 7 Elvington Airfield . 16 2 History . 4 8 Social Aspects of Heslington Today - 3 The Countryside and the Village. 5 Implications for Development . 16 3.1 The Village Setting . 5 9 Commercial. 18 3.2 Open Spaces in and around the Village . 6 10 Roads, Paths and Traffic . 19 3.3 Farming . 9 11 Visual Intrusion and Noise . 21 3.4 The Conservation Area . 10 11.1 Signs and Street Furniture . 21 4 The Built Environment . 13 11.2 Lighting and Security. 22 5 Crime Prevention . 15 11.3 Noise and Disruption . 22 6 Campus 3 Development . 15 Acknowledgements Key to cover photographs (left to right):- This Village Design Statement has been produced with the help Front cover: Heslington Hall; Main Street South; the Paddock; and support of so many that they cannot all be named St Paul’s Church; More House. individually, though the following are recorded who have Back inside cover: details of vernacular building materials in particularly contributed to its text and illustration; Nick Allen, Heslington. Mike Fernie, Angela Fisher, Richard Frost, Peter Hall, Sally Hawkswell, John Hutchinson (illustrations), John Jones, Back outer cover: window, Village Meeting Room; bell-tower, Jon Lovett, Bill McClean, Jeffrey Stern, David Strickland, Lord Deramore's School; window detail, St Paul’s Church, Tony Tolhurst and Ifan Williams. We would also like to thank doorway, number 10 Main Street [South]; headstone of Diane Cragg and Katherine Atkinson of CYC for their help and John West-Taylor (St Paul’s Church); door, Almshouses, advice in the preparation of this document. -

Heslington Road Estate York Yo10 5Bn

HESLINGTON ROAD ESTATE YORK YO10 5BN PRIME YORK DEVELOPMENT OPPORTUNITY Outstanding buildings and grounds of architectural and historical importance forming an exceptional development opportunity Current property for sale is arranged in three zoned lots, comprising approximately 132,000 sq ft (12,263 sq m) on a combined site sale area of circa 12.2 acres, which is situated within an established and picturesque walled 40 acre estate Located off Heslington Road, within 1 mile of York ZONE C: COTTAGE VILLA City Centre with proximity to a full range of services and amenities, including University of York and York • Grade II Listed Railway Station • 7,158 sq ft - 665 sq m • 0.58 acres - 0.23 hectares Offers are sought on a conditional or unconditional basis for whole or part of the property Suitable for a range of redevelopment uses, including residential, care, hotel or leisure, subject to the necessary consents. ZONE B: GARROW HILL HOUSE ZONE A: PRINCIPAL BUILDING • Grade II Listed • Grade II* Listed • 9,408 sq ft - 874 sq m • 115,412 sq ft (10,722 sq m) • 0.78 acres - 0.32 hectares • 10.84 acres - 4.39 hectares YORK RAILWAY STATION YORK MINSTER CLIFFORD’S TOWER HUNGATE RETAIL CORE RIVER OUSE BARBICAN WALMGATE FOSS ISLAND RETAIL PARK YORK CITY WALLS ST NICKS NATURE RESERVE YORK CEMETERY VITA LOW MOOR ALLOTMENTS HULL ROAD PARK WALMGATE STRAY UNIVERSITY OF YORK N L N O T K C O T S D R N O T L A M RD RTH WO HE TA NG H ALL LN 6 D 3 A O 0 1 R A N O T G N I G G I W E P J R A D M O A E D H O S R T R S L L R T HULL ROAD PARKU Y R E E H B Y ET X E -

The Relation of Village and Rural Pubs with Community Life and People’S Well-Being in Great Britain

GJAE 61 (2012), Number 4 The Economics of Beer and Brewing: Selected Contributions of the 2nd Beeronomics Conference The Relation of Village and Rural Pubs with Community Life and People’s Well-Being in Great Britain Der Zusammenhang zwischen ländlichen Pubs und sozialem Zusammenhalt und Lebensqualität in Großbritannien Ignazio Cabras University of York, U.K. Jesus Canduela and Robert Raeside Edinburgh Napier University, U.K. Abstract Proxy für örtliches Wohlbefinden. Die Ergebnisse dieser Arbeit liefern starke Argumente für die Förde- In Great Britain the make-up of rural communities is rung der Erhaltung ländlicher Pubs. changing. Young individuals are moving to cities and the population of rural communities is ageing. In this Schlüsselwörter context, it is important to sustain and enhance peo- ple’s well-being and community cohesion. The pur- ländliche Pubs; sozialer Zusammenhalt; sozio-öko- pose of this paper is to show that pubs are important nomische Entwicklung; ländliches Großbritannien facilitators of community cohesion and ultimately well-being of residents. This is done by compiling a database of secondary data at the parish level of rural 1 Introduction communities of England. From this data, measures of In economically richer countries, social cohesion is community cohesion and social interaction are de- important with regard to individuals’ wellbeing. This rived and correlated with the number of pubs within is particularly true for rural areas. The second half of the parish. Pubs are found to be statistically signifi- the twentieth century and the beginning of the twenty cantly positively associated with community cohesion first century have seen the development of large urban and social interaction.