The Role of Memory in the Transmission of Georgian Chant 501

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

State of Conservation Report by The

au_(_~ b.-,rl.-,~ooaa~(Y)b J'tJ~6'tJ~'tJ~o aaaJao~~a(Y)<'>Ob ~..,e aob a~(Y)a6'tJ ~o b.-,.-,0a66(Y) Georgian National Agency for Cultural Heritage Preservation(,i-1/J. " ..:.'d)___ 0 u (ri _ ..;._ ---------- 201s v· To: Mr. Kishore Rao, Director World Heritage Centre 7, Place de Fontenoy 75352, Paris 07 SP Dear Mr. Rao, In conformity with the decisions of the 38th session of t he World Heritage Committee, held in Do ha, Qatar in 2014, I would like to present for your consideration the State of Conservation report of the Bagrati Cathedral an d Gelati Monastery World Heritage Site as well as the State of Conservation and Progress Re ports of the Historical Monuments of Mtskheta World Heritage Site. On behalf of the National Agency for Cultural Heritage Preservation of Georgia, I would like to reiterate the deep commitment to the implementation of the World Heritage Convention. Please, accept the assurance of my highest consideration. Nikoloz Antidze Director General (;" ~__.:, Annex 1: SoC report Historical Mo uments of Mtskheta Annex 2: Progress Report Historic I Monuments of Mtksheta Annex 3: SoC report Bagrati cathedral and Gelati Monastery 0105. J.m?loS!!_'o ho. m.'>6'Z}t!•'> 030S!!,'O h d· No5, (~lJR'· ( +995 32) 93 24 11, 93 23 94 5 Tabukashvili str. Tbilisi 0105. Tel.(+995 32) 93 24 II, 93 23 94 Bagrati Cathedral and Gelati Monastery, C 710 The present folder contains: 1. State of Conservation Report of the Bagrati Cathedral and Gelati Monastery, C710, Georgia, 2015 Annexes orovided on CD: Annex 1: Metodology report about conservation of building stones of the Early 12th-Century Church of the Virgin at Gelati Monastery in Kutaisi - Stefano Volta Annex 2: Engineering Technical Report Annex 3: Technical Report of the Restoration Works 2. -

A Short History of Georgian Architecture

A SHORT HISTORY OF GEORGIAN ARCHITECTURE Georgia is situated on the isthmus between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea. In the north it is bounded by the Main Caucasian Range, forming the frontier with Russia, Azerbaijan to the east and in the south by Armenia and Turkey. Geographically Georgia is the meeting place of the European and Asian continents and is located at the crossroads of western and eastern cultures. In classical sources eastern Georgia is called Iberia or Caucasian Iberia, while western Georgia was known to Greeks and Romans as Colchis. Georgia has an elongated form from east to west. Approximately in the centre in the Great Caucasian range extends downwards to the south Surami range, bisecting the country into western and eastern parts. Although this range is not high, it produces different climates on its western and eastern sides. In the western part the climate is milder and on the sea coast sub-tropical with frequent rains, while the eastern part is typically dry. Figure 1 Map of Georgia Georgian vernacular architecture The different climates in western and eastern Georgia, together with distinct local building materials and various cultural differences creates a diverse range of vernacular architectural styles. In western Georgia, because the climate is mild and the region has abundance of timber, vernacular architecture is characterised by timber buildings. Surrounding the timber houses are lawns and decorative trees, which rarely found in the rest of the country. The population and hamlets scattered in the landscape. In eastern Georgia, vernacular architecture is typified by Darbazi, a type of masonry building partially cut into ground and roofed by timber or stone (rarely) constructions known as Darbazi, from which the type derives its name. -

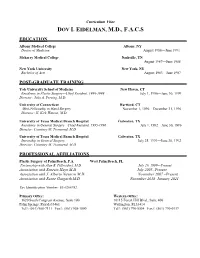

Dov I. Eidelman, Md, Facs

Curriculum Vitae DOV I. EIDELMAN, M.D., F.A.C.S EDUCATION Albany Medical College Albany, NY Doctor of Medicine August 1988—June 1991 Meharry Medical College Nashville, TN August 1987—June 1988 New York University New York, NY Bachelor of Arts August 1983—June 1987 POST-GRADUATE TRAINING Yale University School of Medicine New Haven, CT Residency in Plastic Surgery—Chief Resident, 1998-1999 July 1, 1996—June 30, 1999 Director: John A. Persing, M.D. University of Connecticut Hartford, CT Mini-Fellowship in Hand Surgery November 1, 1996—December 31, 1996 Director: H. Kirk Watson, M.D. University of Texas Medical Branch Hospital Galveston, TX Residency in General Surgery—Chief Resident, 1995-1996 July 1, 1992—June 30, 1996 Director: Courtney M. Townsend, M.D University of Texas Medical Branch Hospital Galveston, TX Internship in General Surgery July 25, 1991—June 30, 1992 Director: Courtney M. Townsend, M.D PROFESSIONAL AFFILIATIONS Plastic Surgery of Palm Beach, P.A. West Palm Beach, FL Partnership with Alan B. Pillersdorf, M.D. July 20, 1999—Present Association with Ernesto Hayn M.D. July 2005- Present Association with J. Alberto Navarro M.D. November 2007 –Present Association with Renee Gasgarth M.D. November 2018–January 2021 Tax Identification Number: 65-0208782 Primary Office: Western Office: 1620 South Congress Avenue, Suite 100 10115 Forest Hill Blvd., Suite 400 Palm Springs, Florida33461 Wellington, FL33414 Tel#: (561) 968-7111 Fax#: (561) 968-1800 Tel#: (561) 790-5554 Fax#: (561) 790-0139 BOARD CERTIFICATION The American Board of Plastic Surgery Board Certified in Plastic Surgery –September 9, 2000 Re-Certified: December 1, 2010 Certification Number: 5962 MEDICAL LICENSURE DEA# BE6316132 (Exp. -

Wine & Brandy Tour 5 Days

WINE & BRANDY TOUR 5 DAYS Private special escorted tour for individuals and families BEST TIME JAN FEB MAR APR MAY JUN JUL AUG SEP OCT NOV DEC History and culture of Georgia have always been closely intertwined with winemaking tradition. Wine in local culture is often considered as a symbol of hospitality and friendship. Oldest evidence of winemaking has been recently discovered at the archaeological site near Tbilisi, at the 8000-year old village. Nowadays there are over 500 species of grape in Georgia, while up to 40 of those varieties are used in commercial wine production. 5-day “Wine and Brandy” introduces you to the Georgian wine. Tour takes off in the capital Tbilisi and travels to the major traditional winemaking region of Georgia – Kakheti. On this tour, travelers will be able to sightsee Tbilisi, visit the best wineries of Kakheti region, taste various local types of wine, and take a look at both modern and traditional ways of wine and brandy production of the country. Group will be accompanied by local, professional and experienced guide and driver MAIN HIGHLIGHTS & SITES: TBILISI CITY KAKHETI REGION • Holy Trinity Cathedral • Signagi town • Narikala Fortress 4Th C • Sighnaghi Pheasant’s Tears wine cellar • Legvtakhevi Waterfall • Winery & museum Numisi in Velistsikhe 16th c • Sulfur bathhouse square • Kvareli Wine Tunnels • Shardeni str & Bridge of Peace • Telavi Town • Meidan square • Telavi Farmer’s Bazaar • Georgian National Museum • Tsinandali Residence of Al. Chavchavadze 19th c • Sarajishvili Brandy Factory • Gremi Royal Residence & Castle 16th c • Funicular Train & Mtatsminda Park • Twin’s Wine Cellar and Museum DAY TO DAY ITINERARY 1 DAY Arrival in Tbilisi Airport-Tbilisi City Tour back to the 4th century. -

Charters: What Survives?

Banner 4-final.qxp_Layout 1 01/11/2016 09:29 Page 1 Charters: what survives? Charters are our main source for twelh- and thirteenth-century Scotland. Most surviving charters were written for monasteries, which had many properties and privileges and gained considerable expertise in preserving their charters. However, many collections were lost when monasteries declined aer the Reformation (1560) and their lands passed to lay lords. Only 27% of Scottish charters from 1100–1250 survive as original single sheets of parchment; even fewer still have their seal attached. e remaining 73% exist only as later copies. Survival of charter collectionS (relating to 1100–1250) GEOGRAPHICAL SPREAD from inStitutionS founded by 1250 Our picture of documents in this period is geographically distorted. Some regions have no institutions with surviving charter collections, even as copies (like Galloway). Others had few if any monasteries, and so lacked large charter collections in the first place (like Caithness). Others are relatively well represented (like Fife). Survives Lost or unknown number of Surviving charterS CHRONOLOGICAL SPREAD (by earliest possible decade of creation) 400 Despite losses, the surviving documents point to a gradual increase Copies Originals in their use in the twelh century. 300 200 100 0 109 0s 110 0s 111 0s 112 0s 113 0s 114 0s 115 0s 116 0s 1170s 118 0s 119 0s 120 0s 121 0s 122 0s 123 0s 124 0s TYPES OF DONOR typeS of donor – Example of Melrose Abbey’s Charters It was common for monasteries to seek charters from those in Lay Lords Kings positions of authority in the kingdom: lay lords, kings and bishops. -

A File in the Online Version of the Kouroo Contexture (Approximately

SETTING THE SCENE FOR THOREAU’S POEM: YET AGAIN WE ATTEMPT TO LIVE AS ADAM 11th Century 1010s 1020s 1030s 1040s 1050s 1060s 1070s 1080s 1090s 12th Century 1110s 1120s 1130s 1140s 1150s 1160s 1170s 1180s 1190s 13th Century 1210s 1220s 1230s 1240s 1250s 1260s 1270s 1280s 1290s 14th Century 1310s 1320s 1330s 1340s 1350s 1360s 1370s 1380s 1390s 15th Century 1410s 1420s 1430s 1440s 1450s 1460s 1470s 1480s 1490s 16th Century 1510s 1520s 1530s 1540s 1550s 1560s 1570s 1580s 1590s 17th Century 1610s 1620s 1630s 1640s 1650s 1660s 1670s 1680s 1690s 18th Century 1710s 1720s 1730s 1740s 1750s 1760s 1770s 1780s 1790s 19th Century 1810s Alas! how little does the memory of these human inhabitants enhance the beauty of the landscape! Again, perhaps, Nature will try, with me for a first settler, and my house raised last spring to be the oldest in the hamlet. To be a Christian is to be Christ- like. VAUDÈS OF LYON 1600 William Gilbert, court physician to Queen Elizabeth, described the earth’s magnetism in DE MAGNETE. Robert Cawdrey’s A TREASURIE OR STORE-HOUSE OF SIMILES. Lord Mountjoy assumed control of Crown forces, garrisoned Ireland, and destroyed food stocks. O’Neill asked for help from Spain. HDT WHAT? INDEX 1600 1600 In about this year Robert Dudley, being interested in stories he had heard about the bottomlessness of Eldon Hole in Derbyshire, thought to test the matter. George Bradley, a serf, was lowered on the end of a lengthy rope. Dudley’s little experiment with another man’s existence did not result in the establishment of the fact that holes in the ground indeed did have bottoms; instead it became itself a source of legend as spinners would elaborate a just-so story according to which serf George was raving mad when hauled back to the surface, with hair turned white, and a few days later would succumb to the shock of it all. -

One Week Tour in Georgia – Imereti and Racha

One week tour in Georgia – Imereti and Racha – Offered by: Foundations from Poland: “Partnerstwo” and “Together for Rural Development” with ”International Center for Caucasus Tourism” (ICCT) from Georgia Autumn offer WHERE: Imereti – Racha (Georgia) WHEN: September-October HOW: Direct flights to Kutaisi from many European cities PRICE: € 500,0 + flight cost ON-SITE: insurance, accommodation, meals, guided tours and guaranteed unforgettable impressions GROUP: maximum 15 person I NVITE : P OLISH FUNDS "TOGETHER FOR RURAL DEVELOPMENT ”&" P ARTNERSTVO "&"I NTERNATIONAL C ENTER FOR C AUCASUS T OURISM “ I C C T How to reach Kutaisi? • DIRECT flights to KUTAISI “Kopitnari” FROM: Barcelona, Berlin, Birmingham, Budapest, Dortmund, Katowice, Larnaca, Memmingen, Milan, Moscow, Paris, Prague, Riga, Thessaloniki, Vilnius, Warsaw, Wroclaw. Flights schedule with present time http://kutaisi.aero/Flights • Georgian Currency GEL (Lari) (USD: 2.57; EUR: 2.92). Withdrawing of GEL from ATM from your card or exchange USD /EUR into GEL at the relevant points. • Language – Georgian, possibility to communicate in English, Polish and Kutaisi Russian (mostly with aged people) ქუთაისი • Convenient dress - sports ware Kopitnari • Perceptible temperature – about +18 კოპიტნარი • Telephone code +995 NOTE: - Air ticket price changes daily. The above mentioned cost reflects the situation on 18th August 2018 - One can buy a group ticket (more than 9 people) Map of KUTAISI Google Map image highlights the most important tourist destinations in the city. The system "Street -

Tentative Lists Submitted by States Parties As of 15 April 2014, in Conformity with the Operational Guidelines

World Heritage 38 COM WHC-14/38.COM/8A Paris, 6 June 2014 Original: English / French UNITED NATIONS EDUCATIONAL, SCIENTIFIC AND CULTURAL ORGANIZATION CONVENTION CONCERNING THE PROTECTION OF THE WORLD CULTURAL AND NATURAL HERITAGE WORLD HERITAGE COMMITTEE Thirty-eighth session Doha, Qatar 15 – 25 June 2014 Item 8 of the Provisional Agenda: Establishment of the World Heritage List and of the List of World Heritage in Danger 8A. Tentative Lists submitted by States Parties as of 15 April 2014, in conformity with the Operational Guidelines SUMMARY This document presents the Tentative Lists of all States Parties submitted in conformity with the Operational Guidelines as of 15 April 2014. The World Heritage Committee is requested to note that all nominations of properties to be examined by the 38th session of the Committee are included on the Tentative Lists of the respective States Parties. • Annex 1 presents a full list of States Parties indicating the date of the most recent Tentative List submission; • Annex 2 presents new Tentative Lists (or additions to Tentative Lists) submitted by States Parties since the last session of the World Heritage Committee; • Annex 3 presents a list of all properties submitted on Tentative Lists received from the States Parties, in alphabetical order. Draft Decision: 38 COM 8A, see Point II I. EXAMINATION OF TENTATIVE LISTS 1. The World Heritage Committee requests each State Party to submit an inventory of the cultural and natural properties situated within its territory, which it considers suitable for inscription on the World Heritage List, and which it intends to nominate during the following five to ten years. -

Acceptance and Rejection of Foreign Influence in the Church Architecture of Eastern Georgia

The Churches of Mtskheta: Acceptance and Rejection of Foreign Influence in the Church Architecture of Eastern Georgia Samantha Johnson Senior Art History Thesis December 14, 2017 The small town of Mtskheta, located near Tbilisi, the capital of the Republic of Georgia, is the seat of the Georgian Orthodox Church and is the heart of Christianity in the country. This town, one of the oldest in the nation, was once the capital and has been a key player throughout Georgia’s tumultuous history, witnessing not only the nation’s conversion to Christianity, but also the devastation of foreign invasions. It also contains three churches that are national symbols and represent the two major waves of church building in the seventh and eleventh centuries. Georgia is, above all, a Christian nation and religion is central to its national identity. This paper examines the interaction between incoming foreign cultures and deeply-rooted local traditions that have shaped art and architecture in Transcaucasia.1 Nestled among the Caucasus Mountains, between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea, present-day Georgia contains fewer than four million people and has its own unique alphabet and language as well as a long, complex history. In fact, historians cannot agree on how Georgia got its English exonym, because in the native tongue, kartulad, the country is called Sakartvelo, or “land of the karvelians.”2 They know that the name “Sakartvelo” first appeared in texts around 800 AD as another name for the eastern kingdom of Kartli in Transcaucasia. It then evolved to signify the unified eastern and western kingdoms in 1008.3 Most scholars agree that the name “Georgia” did not stem from the nation’s patron saint, George, as is commonly thought, but actually comes 1 This research addresses the multitude of influences that have contributed to the development of Georgia’s ecclesiastical architecture. -

Georgian Country and Culture Guide

Georgian Country and Culture Guide მშვიდობის კორპუსი საქართველოში Peace Corps Georgia 2017 Forward What you have in your hands right now is the collaborate effort of numerous Peace Corps Volunteers and staff, who researched, wrote and edited the entire book. The process began in the fall of 2011, when the Language and Cross-Culture component of Peace Corps Georgia launched a Georgian Country and Culture Guide project and PCVs from different regions volunteered to do research and gather information on their specific areas. After the initial information was gathered, the arduous process of merging the researched information began. Extensive editing followed and this is the end result. The book is accompanied by a CD with Georgian music and dance audio and video files. We hope that this book is both informative and useful for you during your service. Sincerely, The Culture Book Team Initial Researchers/Writers Culture Sara Bushman (Director Programming and Training, PC Staff, 2010-11) History Jack Brands (G11), Samantha Oliver (G10) Adjara Jen Geerlings (G10), Emily New (G10) Guria Michelle Anderl (G11), Goodloe Harman (G11), Conor Hartnett (G11), Kaitlin Schaefer (G10) Imereti Caitlin Lowery (G11) Kakheti Jack Brands (G11), Jana Price (G11), Danielle Roe (G10) Kvemo Kartli Anastasia Skoybedo (G11), Chase Johnson (G11) Samstkhe-Javakheti Sam Harris (G10) Tbilisi Keti Chikovani (Language and Cross-Culture Coordinator, PC Staff) Workplace Culture Kimberly Tramel (G11), Shannon Knudsen (G11), Tami Timmer (G11), Connie Ross (G11) Compilers/Final Editors Jack Brands (G11) Caitlin Lowery (G11) Conor Hartnett (G11) Emily New (G10) Keti Chikovani (Language and Cross-Culture Coordinator, PC Staff) Compilers of Audio and Video Files Keti Chikovani (Language and Cross-Culture Coordinator, PC Staff) Irakli Elizbarashvili (IT Specialist, PC Staff) Revised and updated by Tea Sakvarelidze (Language and Cross-Culture Coordinator) and Kakha Gordadze (Training Manager). -

GEORGIAN HOLIDAYS 15 DAYS Private Special Tour, Escorted Long Joutney for Individuals and Families

GEORGIAN HOLIDAYS 15 DAYS Private special tour, escorted long joutney for individuals and families BEST TIME JAN FEB MAR APR MAY JUN JUL AUG SEP OCT NOV DEC The aim of 15-day itinerary “Georgian Holidays” is to introduce travelers to all parts of Georgia and let them experience the diversity of nature and society of the country. Tour takes off in the capital Tbilisi, and travels through every corner of Georgia. Visitors are going to sightsee major cities and towns, provinces in the highlands of the Greater and Lesser Caucasus mountains, the shores of the Black Sea, natural wonders of the West Georgia, traditional wine-making areas in the east, and all major historico-cultural monuments of the country. Tour will be accompanied by professional and experienced guide and driver that will make your journey smooth, informational and unforgettable. MAIN HIGHLIGHTS & SITES: TBILISI CITY MTSKHETA CITY SAMEGRELO REGION • the Holy Trinity Cathedral of Tbilisi • Jvari Monastery • Zugdidi Town • Metekhi church • Svetitskhoveli Cathedral • Dadiani Palace • Narikala Fortress • Legvtakhevi KHEVI REGION SVANETI REGION • Sulfur bathhouses • Gudauri ski resort • Ushguli community • Shardeni street • Ananuri Architectural Complex • Villages Ipari and Kala • Maidan square • Kazbegi • Mestia • Margiani Museum • Caravanserai – Tbilisi History Museum • Gergeti Trinity Church • Dariali gorge • Svaneti Museum • Bridge of Peace • Gveleti waterfalls • National Museum of Georgia ADJARA PROVINCE • Rustaveli Avenue KARTLI REGION • Batumi city • Gori town • Batumi Boulevard & Piazza square KAKHETI REGION • Stalin’s house-museum • Gonio Fortress • David Gareja Monastery • Uplistsikhe Cave Complex • Batumi Botanical Garden • Signagi • Bodbe monastery IMERETI REGION SAMTSKHE-JAVAKHETI REGION • Velistskhe family winery “Numisi” • Kutaisi city • Borjomi spa-resort • House Museum of Al. -

Bresnan Communications ) CSR No

Federal Communications Commission DA 00-1635 Before the Federal Communications Commission Washington, D.C. 20554 In the Matter of ) ) CUID No. GA0378 (Richmond Hill) Bresnan Communications ) CSR No. 4746-R ) Complaint Regarding Cable Programming ) Services Tier Rate and Cost of Service ) Showing to Support Basic Service Tier Rate ) ORDER Adopted: July 20, 2000 Released: July 24, 2000 By the Acting Chief, Financial Analysis and Compliance Division, Cable Services Bureau: 1. In this Order we consider a complaint against the October 1, 1995 rate increase of the above-referenced operator ("Operator") for its cable programming services tier ("CPST") in the community referenced above. In this Order we also review the FCC Form 1235 (Abbreviated Cost of Service Filing for Cable Network Upgrades) filed to support the rate Operator was charging for its basic service tier ("BST") in the community referenced above. On February 12, 1996, the City of Richmond Hill petitioned the Federal Communications Commission ("Commission") requesting assistance in reviewing Operator's BST cost of service showing.1 The Commission granted the City's request on July 8, 1996, and agreed to review Operator's FCC Form 1235 abbreviated cost of service showing regarding its BST rate.2 This Order addresses the reasonableness of Operator's October 1, 1995 CPST rate increase and the reasonableness of Operator’s calculated FCC Form 1235 maximum permitted rate ("MPR") for the BST. 2. Under the Communications Act,3 the Commission is authorized to review the CPST rates of cable systems not subject to effective competition to ensure that rates charged are not unreasonable. The Cable Television Consumer Protection and Competition Act of 19924 ("1992 Cable Act") required the Commission to review CPST rates upon the filing of a valid complaint by a subscriber or local franchising authority ("LFA").