I'm Here Implementation—El Obour, Greater Cairo, Egypt

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Encouraging Peaceful Co-Existence Through a Multi-Faceted Approach

Encouraging Peaceful Co-Existence Through a Multi-Faceted Approach Implementing Agency: Plan International Egypt Partners: Syria Al Gad Relief Foundation in Greater Cairo and Islamic Charity Complex Association in Damietta Donor: European Commission- Humanitarian Aid and Civil Protection Location: Damietta and Qalubia (Greater Cairo) Target Population: Syrian and Egyptian students ages 0 – 18 years Implementation Period: June 1, 2016 - May 31, 2018 Number of Beneficiaries: 3600 children and 60 adults 1200 children, 0 – 5 years 1900 children, 6 – 12 years 500 children, 13 – 18 years 60 teachers and school management Background The violence in Syria has seen over 2.2 million child refugees fleeing to other countries, and 6 million children in need of assistance, including 2.8 million displaced, inside Syria. UNHCR reports that circa 51,000 Syrian child refugees registered, 1,600 of them are separated, all in need of assistance. The initial findings of an on-going UNHCR-led survey show that between 20 and 30 percent of Syrian refugee children in Egypt are out of school, compared to 12 percent in 2014. Damietta and Qalubia are two of the governorates with high numbers of Syrian refugees and limited humanitarian support. In response, Plan International (Plan) set up an office in Damietta to help Syrian children to fulfill their right to education and integrate in host communities. Plan’s Qalubia sub-office has been supporting public schools to accept and cater for the needs of refugee children. In this action, Plan is working with the Ministry of Education to integrate 7,590 Syrian refugee children aged 0-18 years in six communities of the Damietta and Qalubia governorates, promoting a safe and socially inclusive environment and supporting their smooth integration in host communities. -

Obour Land OBOUR LAND for Food Industries Mosque Ofsultanhassan -Cairo W BP802AR 350P

Food Sector Obour City - Cairo, Egypt Shrinkwrapper BP802AR 350P hen speaking about Egypt we immediately think of an ancient Wcivilization filled with art, culture, magic and majesty closely related to one of the most enigmatic and recognized cities in the world, the capital of the state and one of the principal centers of development in the old world. Being the most populous city in the entire African continent, Cairo is For Food Industries among the most important industrial and commercial points in the Middle East, and a big development center for the cotton, silk, glass and food products industries which, thanks to the commitment of its people, is constantly growing. The food industry is largely responsible for this development, having the objective of positioning quality products on the market that meet the needs of end customers, improving production processes and giving priority to investments in cutting-edge technologies that allow to achieve this end. A clear example of this commitment is represented by the Obour Land Company which, among its numerous investments, has recently acquired 7 Smipack machines model BP802AR 350P. Mosque of Sultan Hassan - Cairo OBOUR LAND 2 | Obour Land Obour Land | 3 Egyptian Museum - Cairo eing the capital of one of the most important countries in Africa, with a population growth of around 2% per year(1), Cairo has one of the fastest growing markets for food Band agricultural products in the world. The growth city in constant growth of the agri-food and manufacturing sector in Egypt is CAIRO associated -

ACLED) - Revised 2Nd Edition Compiled by ACCORD, 11 January 2018

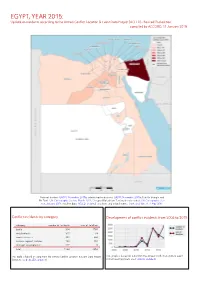

EGYPT, YEAR 2015: Update on incidents according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) - Revised 2nd edition compiled by ACCORD, 11 January 2018 National borders: GADM, November 2015b; administrative divisions: GADM, November 2015a; Hala’ib triangle and Bir Tawil: UN Cartographic Section, March 2012; Occupied Palestinian Territory border status: UN Cartographic Sec- tion, January 2004; incident data: ACLED, undated; coastlines and inland waters: Smith and Wessel, 1 May 2015 Conflict incidents by category Development of conflict incidents from 2006 to 2015 category number of incidents sum of fatalities battle 314 1765 riots/protests 311 33 remote violence 309 644 violence against civilians 193 404 strategic developments 117 8 total 1244 2854 This table is based on data from the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project This graph is based on data from the Armed Conflict Location & Event (datasets used: ACLED, undated). Data Project (datasets used: ACLED, undated). EGYPT, YEAR 2015: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) - REVISED 2ND EDITION COMPILED BY ACCORD, 11 JANUARY 2018 LOCALIZATION OF CONFLICT INCIDENTS Note: The following list is an overview of the incident data included in the ACLED dataset. More details are available in the actual dataset (date, location data, event type, involved actors, information sources, etc.). In the following list, the names of event locations are taken from ACLED, while the administrative region names are taken from GADM data which serves as the basis for the map above. In Ad Daqahliyah, 18 incidents killing 4 people were reported. The following locations were affected: Al Mansurah, Bani Ebeid, Gamasa, Kom el Nour, Mit Salsil, Sursuq, Talkha. -

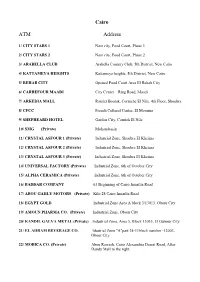

Cairo ATM Address

Cairo ATM Address 1/ CITY STARS 1 Nasr city, Food Court, Phase 1 2/ CITY STARS 2 Nasr city, Food Court, Phase 2 3/ ARABELLA CLUB Arabella Country Club, 5th District, New Cairo 4/ KATTAMEYA HEIGHTS Kattameya heights, 5th District, New Cairo 5/ REHAB CITY Opened Food Court Area El Rehab City 6/ CARREFOUR MAADI City Center – Ring Road, Maadi 7/ ARKEDIA MALL Ramlet Boulak, Corniche El Nile, 4th Floor, Shoubra 8/ CFCC French Cultural Center, El Mounira 9/ SHEPHEARD HOTEL Garden City, Cornish El Nile 10/ SMG (Private) Mohandessin 11/ CRYSTAL ASFOUR 1 (Private) Industrial Zone, Shoubra El Kheima 12/ CRYSTAL ASFOUR 2 (Private) Industrial Zone, Shoubra El Kheima 13/ CRYSTAL ASFOUR 3 (Private) Industrial Zone, Shoubra El Kheima 14/ UNIVERSAL FACTORY (Private) Industrial Zone, 6th of October City 15/ ALPHA CERAMICA (Private) Industrial Zone, 6th of October City 16/ BADDAR COMPANY 63 Beginning of Cairo Ismailia Road 17/ ABOU GAHLY MOTORS (Private) Kilo 28 Cairo Ismailia Road 18/ EGYPT GOLD Industrial Zone Area A block 3/13013, Obour City 19/ AMOUN PHARMA CO. (Private) Industrial Zone, Obour City 20/ KANDIL GALVA METAL (Private) Industrial Zone, Area 5, Block 13035, El Oubour City 21/ EL AHRAM BEVERAGE CO. Idustrial Zone "A"part 24-11block number -12003, Obour City 22/ MOBICA CO. (Private) Abou Rawash, Cairo Alexandria Desert Road, After Dandy Mall to the right. 23/ COCA COLA (Pivate) Abou El Ghyet, Al kanatr Al Khayreya Road, Kaliuob Alexandria ATM Address 1/ PHARCO PHARM 1 Alexandria Cairo Desert Road, Pharco Pharmaceutical Company 2/ CARREFOUR ALEXANDRIA City Center- Alexandria 3/ SAN STEFANO MALL El Amria, Alexandria 4/ ALEXANDRIA PORT Alexandria 5/ DEKHILA PORT El Dekhila, Alexandria 6/ ABOU QUIER FERTLIZER Eltabia, Rasheed Line, Alexandria 7/ PIRELLI CO. -

Analysis of the Retailer Value Chain Segment in Five Governorates Improving Employment and Income Through Development Of

Analysis of the retailer value chain segment in five governorates Item Type monograph Authors Hussein, S.; Mounir, E.; Sedky, S.; Nour, S.A. Publisher WorldFish Download date 30/09/2021 17:09:21 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/1834/27438 Analysis of the Retailer Value Chain Segment in Five Governorates Improving Employment and Income through Development of Egypt’s Aquaculture Sector IEIDEAS Project July 2012 Samy Hussein, Eshak Mounir, Samir Sedky, Susan A. Nour, CARE International in Egypt Executive Summary This study is the third output of the SDC‐funded “Improving Employment and Income through Development of Egyptian Aquaculture” (IEIDEAS), a three‐year project being jointly implemented by the WorldFish Center and CARE International in Egypt with support from the Ministry of Agriculture and Land Reclamation. The aim of the study is to gather data on the retailer segment of the aquaculture value chain in Egypt, namely on the employment and market conditions of the women fish retailers in the five target governorates. In addition, this study provides a case study in Minya and Fayoum of the current income levels and standards of living of this target group. Finally, the study aims to identify the major problems and obstacles facing these women retailers and suggest some relevant interventions. CARE staff conducted the research presented in this report from April to July 2012, with support from WorldFish staff and consultants. Methodology The study team collected data from a variety of sources, through a combination of primary and secondary data collection. Some of the sources include: 1. In‐depth interviews and focus group discussions with women retailres 2. -

Analysis of Urban Growth at Cairo, Egypt Using Remote Sensing and GIS

Vol.4, No.6, 355-361 (2012) Natural Science http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ns.2012.46049 Analysis of urban growth at Cairo, Egypt using remote sensing and GIS Mohamed E. Hereher Department of Environmental Sciences, Faculty of Science at Damietta, Mansoura University, Mansoura, Egypt; [email protected] Received 21 January 2012; revised 22 February 2012; accepted 11 March 2012 ABSTRACT by the Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (SRTM) on- board the Space Shuttle Endeavor in its journey during The main objective of the present study was to Dec. 2000. DEM images are available in 30, 90 and 1000 highlight and analyze the exchange between the m spatial resolutions. The 30 m resolution DEMs are land cover components at Cairo with focusing available only to the United States, whereas the 90 m and on urban area and agricultural land between 1000 m resolution are available to the entire world and 1973 and 2006 using Landsat satellite data with could be accessed from the United States Geological the aid of Digital Elevation Models (DEM). The Survey (USGS) online open resources. techniques utilized in this investigation involved In Egypt, remote sensing and its applications have a rigorous supervised classification of the Land- emerged as early as this technology was invented. Early sat and the DEM images. Results showed that 2 studies were based on visual interpretation of MSS data urban area of Cairo was 233.78 km in 1973 and to map sand accumulations in the Western Desert [2]. increased to 557.87 km2 in 2006. The cut-off from 2 During 1980s, soil salinization was a good target to mo- agricultural lands was 136.75 km , whereas ur- nitor in satellite images [3]. -

Obour Land for Food Industries S.A.E

OBOUR LAND FOR FOOD INDUSTRIES S.A.E. 9M2017 EARNINGS RELEASE Obour Land continues to deliver strong double-digit top-line growth at 39% in 9M17; bottom line likewise turns an exceptional 60% y-o-y growth despite the challenging economic environment Key Highlights y-o-y All figures are in EGP unless stated otherwise 9M17 9M16 Change Net Revenues 1,462mn 1,054mn 39% Volume Sold 70k tons 74k tons (6%) Average price/kg 21.0 14.3 47% Gross Profit 354mn 220mn 61% Gross Profit Margin 24% 21% +3pp EBITDA 251mn 153mn 64% EBITDA Margin 17% 15% +2pp Net Profit 176mn 110mn 60% Net Profit Margin 12% 10% +2pp Cairo, Egypt | November 9, 2017 - Obour Land for Food Industries S.A.E. (OLFI) announced its 9M2017 results for the 9-month period starting January 2017. The Company’s sales for the period recorded EGP 1.46bn, posting a growth of 39% y-o-y (compared to the same period last year). Total volume sold in 9M17 reached 70 thousand tons, a 6% y-o-y decline mainly driven by decreasing consumer purchasing power, while average price per kilogram increased by 47% y-o-y to reach EGP 21 during 9M17. The witnessed growth in the Company’s sales performance was mainly driven by the increase in prices, along with the successful sales strategy and marketing campaigns adopted during the period. The Company recorded gross profit of EGP 354mn during 9M17, posting a y-o-y growth of 61%, translating into a gross profit margin of 24%, compared to 21% in 9M16. -

Privatization in Egypt

PPrriivvaattiizzaattiioonn iinn EEggyypptt Quarterly Review April – June 2003 Privatization Implementation Project www.egyptpip.com Implemented by IBM Business Consulting Services Funded by USAID Quarterly Report January - March 2003 Privatization in Egypt Table of Contents A. PRIVATIZATION EFFORTS WITH LAW 203 COMPANIES............................8 B. DISSOLUTION OF THE HOLDING COMPANY FOR ENGINEERING INDUSTRIES..........................................................................................................9 C. PRIVATIZATION BY CAPITALIZATION – CURRENT STATUS..................11 1. Engineering Automotive Company (EAMC) ..................................................................12 2. EDFINA Company for Preserved Foods ........................................................................13 3. Kom Hamada Spinning Company.....................................................................................14 4. El Mahmodeya Spinning & Weaving Company ..............................................................15 5. El Nasr Company for Rubber Products (NARUBIN)...................................................16 6. El Nasr for Electric and Electronic Apparatus S.A.E. (NEEASAE)...........................17 7. The General Egyptian Company for Railway Wagons & Coaches (SEMAF) ............18 8. Dyestuffs and Chemicals Company...................................................................................19 D. LAW 203 TENDER ANNOUNCEMENTS......................................................... 20 E. SELECTED JOINT VENTURE -

Food Safety Inspection in Egypt Institutional, Operational, and Strategy Report

FOOD SAFETY INSPECTION IN EGYPT INSTITUTIONAL, OPERATIONAL, AND STRATEGY REPORT April 28, 2008 This publication was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared by Cameron Smoak and Rachid Benjelloun in collaboration with the Inspection Working Group. FOOD SAFETY INSPECTION IN EGYPT INSTITUTIONAL, OPERATIONAL, AND STRATEGY REPORT TECHNICAL ASSISTANCE FOR POLICY REFORM II CONTRACT NUMBER: 263-C-00-05-00063-00 BEARINGPOINT, INC. USAID/EGYPT POLICY AND PRIVATE SECTOR OFFICE APRIL 28, 2008 AUTHORS: CAMERON SMOAK RACHID BENJELLOUN INSPECTION WORKING GROUP ABDEL AZIM ABDEL-RAZEK IBRAHIM ROUSHDY RAGHEB HOZAIN HASSAN SHAFIK KAMEL DARWISH AFKAR HUSSAIN DISCLAIMER: The author’s views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY...................................................................................... 1 INSTITUTIONAL FRAMEWORK ......................................................................... 3 Vision 3 Mission ................................................................................................................... 3 Objectives .............................................................................................................. 3 Legal framework..................................................................................................... 3 Functions............................................................................................................... -

Governorate Area Type Provider Name Card Specialty Address Telephone 1 Telephone 2

Governorate Area Type Provider Name Card Specialty Address Telephone 1 Telephone 2 Metlife Clinic - Cairo Medical Center 4 Abo Obaida El bakry St., Roxy, Cairo Heliopolis Metlife Clinic 02 24509800 02 22580672 Hospital Heliopolis Emergency- 39 Cleopatra St. Salah El Din Sq., Cairo Heliopolis Hospital Cleopatra Hospital Gold Outpatient- 19668 Heliopolis Inpatient ( Except Emergency- 21 El Andalus St., Behind Cairo Heliopolis Hospital International Eye Hospital Gold 19650 Outpatient-Inpatient Mereland , Roxy, Heliopolis Emergency- Cairo Heliopolis Hospital San Peter Hospital Green 3 A. Rahman El Rafie St., Hegaz St. 02 21804039 02 21804483-84 Outpatient-Inpatient Emergency- 16 El Nasr st., 4th., floor, El Nozha Cairo Heliopolis Hospital Ein El Hayat Hospital Green 02 26214024 02 26214025 Outpatient-Inpatient El Gedida Cairo Medical Center - Cairo Heart Emergency- 4 Abo Obaida El bakry St., Roxy, Cairo Heliopolis Hospital Silver 02 24509800 02 22580672 Center Outpatient-Inpatient Heliopolis Inpatient Only for 15 Khaled Ibn El Walid St. Off 02 22670702 (10 Cairo Heliopolis Hospital American Hospital Silver Gynecology and Abdel Hamid Badawy St., Lines) Obstetrics Sheraton Bldgs., Heliopolis 9 El-Safa St., Behind EL Seddik Emergency - Cairo Heliopolis Hospital Nozha International Hospital Silver Mosque, Behind Sheraton 02 22660555 02 22664248 Inpatient Only Heliopolis, Heliopolis 91 Mohamed Farid St. El Hegaz Cairo Heliopolis Hospital Al Dorrah Heart Care Hospital Orange Outpatient-Inpatient 02 22411110 Sq., Heliopolis 19 Tag El Din El Sobky st., from El 02 2275557-02 Cairo Heliopolis Hospital Egyheart Center Orange Outpatient 01200023220 Nozha st., Ard El Golf, Heliopolis 22738232 2 Samir Mokhtar st., from Nabil El 02 22681360- Cairo Heliopolis Hospital Egyheart Center Orange Outpatient 01200023220 Wakad st., Ard El Golf, Heliopolis 01225320736 Dr. -

ATM Branch Branch Address Area Gameat El Dowal El

ATM Branch Branch address Area Gameat El Dowal Gameat El Dowal 9 Gameat El-Dewal El-Arabia Mohandessein, Giza El Arabeya Thawra El-Thawra 18 El-Thawra St. Heliopolis, Heliopolis, Cairo Cairo 6th of October 6th of October Banks area - industrial zone 4 6th of October City, Giza Zizenia Zizenia 601 El-Horaya St Zizenya , Alexandria Champollion Champollion 5 Champollion St., Down Town, Cairo New Hurghada Sheraton Hurghada Sheraton Road 36 North Mountain Road, Hurghada, Red Sea Hurghada, Red Sea Mahatta Square El - Mahatta Square 1 El-Mahatta Square Sarayat El Maadi, Cairo New Maadi New Maadi 48 Al Nasr Avenu New Maadi, Cairo Shoubra Shoubra 53 Shobra St., Shoubra Shoubra, Cairo Abassia Abassia 111 Abbassia St., Abassia Cairo Manial Manial Palace 78 Manial St., Cairo Egypt Manial , Cairo Hadayek El Kobba Hadayek El Kobba 16 Waly El-Aahd St, Saray El- Hdayek El Kobba, Cairo Hadayek Mall Makram Ebeid Makram Ebeid 86, Makram Ebeid St Nasr City, Cairo Abbass El Akkad Abbass El Akkad 20 Abo El Ataheya str. , Abas Nasr City, Cairo El akad Ext Tayaran Tayaran 32 Tayaran St. Nasr City, Cairo House of Financial Affairs House of Financial Affairs El Masa, Abdel Azziz Shenawy Nasr City, Cairo St., Parade Area Mansoura 2 El Mohafza Square 242 El- Guish St. El Mohafza Square, Mansoura Aghakhan Aghakhan 12th tower nile towers Aghakhan, Cairo Aghakhan Dokki Dokki 64 Mossadak Street, Dokki Dokki, Giza El- Kamel Mohamed El_Kamel Mohamed 2, El-Kamel Mohamed St. Zamalek, Cairo El Haram El Haram 360 Al- Haram St. Haram, Giza NOZHA ( Triumph) Nozha Triumph.102 Osman Ebn Cairo Affan Street, Heliopolis Safir Nozha 60, Abo Bakr El-Seddik St. -

Decree-Law of the President of the Arab Republic of Egypt No

The Official Gazette Issue no. 51 (bis.) on December 21st 2014 Page (2) Decree-Law of the President of the Arab Republic of Egypt no. 202/2014 Concerning Electoral Districting for the Elections of the House of Representatives The President of the Republic Having perused: the Constitution; Decree-Law no. 45/2014 on the regulation of the Exercise of Political Rights; Decree-Law no. 46/2014 on the House of Representatives; Upon consulting the High Elections Committee; Upon the approval of the Council of Ministers; and On the basis of the opinion of the Council of State; Decided on the following Law: Article 1 The provisions of the attached law shall apply with regard to the first elections for the House of Representatives that is held after its entry into force and any related by-elections. Any provision contradicting the provisions of the attached law is hereby abolished. Article 2 The Arab Republic of Egypt shall be divided into 237 electoral districts (constituencies) under the Individual-Seat system, and 4 constituencies under the lists system. Article 3 The scope and units of each constituency and the number of seats allocated thereto, and to each Governorate, shall be pursuant to the attached tables, in a manner which observes the fair representation of the population and Governorates and the equitable representation of voters. Article 4 This decree-law and the tables attached thereto shall be published in the Official Gazette and shall enter into force as of the day following its date of publication. Issued at the Presidency of the Republic on the 29th of Safar, 1436 A.H.