BEV Taxi Pilot Program Resolution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vehicle Conversions, Retrofits, and Repowers ALTERNATIVE FUEL VEHICLE CONVERSIONS, RETROFITS, and REPOWERS

What Fleets Need to Know About Alternative Fuel Vehicle Conversions, Retrofits, and Repowers ALTERNATIVE FUEL VEHICLE CONVERSIONS, RETROFITS, AND REPOWERS Acknowledgments This work was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) under Contract No. DE-AC36-08GO28308 with Alliance for Sustainable Energy, LLC, the Manager and Operator of the National Renewable Energy Laboratory. This work was made possible through funding provided by National Clean Cities Program Director and DOE Vehicle Technologies Office Deployment Manager Dennis Smith. This publication is part of a series. For other lessons learned from the Clean Cities American Recovery and Reinvestment (ARRA) projects, please refer to the following publications: • American Recovery and Reinvestment Act – Clean Cities Project Awards (DOE/GO-102016-4855 - August 2016) • Designing a Successful Transportation Project – Lessons Learned from the Clean Cities American Recovery and Reinvestment Projects (DOE/GO-102017-4955 - September 2017) Authors Kay Kelly and John Gonzales, National Renewable Energy Laboratory Disclaimer This document is not intended for use as a “how to” guide for individuals or organizations performing a conversion, repower, or retrofit. Instead, it is intended to be used as a guide and resource document for informational purposes only. VEHICLE TECHNOLOGIES OFFICE | cleancities.energy.gov 2 ALTERNATIVE FUEL VEHICLE CONVERSIONS, RETROFITS, AND REPOWERS Table of Contents Introduction ...............................................................................................................................................................5 -

Electric Vehicle Fleet Toolkit

ELECTRICITY Electricity WHAT IS CHARGING? What is a PEV? A plug-in electric vehicle (PEV) is a How many stations are in the San vehicle in which there is an onboard Diego region? battery that is powered by energy Currently there are over 550 public delivered from the electricity grid. There are two types of electric charging stations in the San Diego region. Level 1 Charging vehicles: a battery electric vehicle Level 1 charging uses 120 volts AC. An PEV (BEV) and a plug-in hybrid electric How much does it cost to fuel my can be charged with just a standard wall vehicle (PHEV). BEVs run exclusively vehicle? outlet. on the power from their onboard battery. PHEVs have both an It generally costs less than half as onboard battery and an internal much to drive an electric vehicle as Level 2 Charging combustion engine that is used an internal combustion engine Level 2 charging uses 240 volts AC. This is when the car’s battery is depleted. the same type of voltage as an outlet used for a dryer or washing machine. There are upwards of 12,000 PEVs in 24-month average* the San Diego region (as of Summer Gasoline $3.35 2015). DC Fast Charging Electricity** $1.22 DC fast charging is a very quick level of charging. An PEV can be charged up to 80% Savings $2.13 within 30 minutes of charging. *June 2013-June 2015 **Gasoline gallon equivalent 1 ELECTRICITY What types of vehicles can use electricity? Electric vehicles come in all shapes and sizes. -

A Comprehensive Study of Key Electric Vehicle (EV) Components, Technologies, Challenges, Impacts, and Future Direction of Development

Review A Comprehensive Study of Key Electric Vehicle (EV) Components, Technologies, Challenges, Impacts, and Future Direction of Development Fuad Un-Noor 1, Sanjeevikumar Padmanaban 2,*, Lucian Mihet-Popa 3, Mohammad Nurunnabi Mollah 1 and Eklas Hossain 4,* 1 Department of Electrical and Electronic Engineering, Khulna University of Engineering and Technology, Khulna 9203, Bangladesh; [email protected] (F.U.-N.); [email protected] (M.N.M.) 2 Department of Electrical and Electronics Engineering, University of Johannesburg, Auckland Park 2006, South Africa 3 Faculty of Engineering, Østfold University College, Kobberslagerstredet 5, 1671 Kråkeroy-Fredrikstad, Norway; [email protected] 4 Department of Electrical Engineering & Renewable Energy, Oregon Tech, Klamath Falls, OR 97601, USA * Correspondence: [email protected] (S.P.); [email protected] (E.H.); Tel.: +27-79-219-9845 (S.P.); +1-541-885-1516 (E.H.) Academic Editor: Sergio Saponara Received: 8 May 2017; Accepted: 21 July 2017; Published: 17 August 2017 Abstract: Electric vehicles (EV), including Battery Electric Vehicle (BEV), Hybrid Electric Vehicle (HEV), Plug-in Hybrid Electric Vehicle (PHEV), Fuel Cell Electric Vehicle (FCEV), are becoming more commonplace in the transportation sector in recent times. As the present trend suggests, this mode of transport is likely to replace internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles in the near future. Each of the main EV components has a number of technologies that are currently in use or can become prominent in the future. EVs can cause significant impacts on the environment, power system, and other related sectors. The present power system could face huge instabilities with enough EV penetration, but with proper management and coordination, EVs can be turned into a major contributor to the successful implementation of the smart grid concept. -

Morgan Ellis Climate Policy Analyst and Clean Cities Coordinator DNREC [email protected] 302.739.9053

CLEAN TRANSPORTATION IN DELAWARE WILMAPCO’S OUR TOWN CONFERENCE THE PRESENTATION 1) What are alterative fuels? 2) The Fuels 3) What’s Delaware Doing? WHAT ARE ALTERNATIVE FUELED VEHICLES? • “Vehicles that run on a fuel other than traditional petroleum fuels (i.e. gas and diesel)” • Propane • Natural Gas • Electricity • Biodiesel • Ethanol • Hydrogen THERE’S A FUEL FOR EVERY FLEET! DELAWARE’S ALTERNATIVE FUELS • “Vehicles that run on a fuel other than traditional petroleum fuels (i.e. gas and diesel)” • Propane • Natural Gas • Electricity • Biodiesel • Ethanol • Hydrogen THE FUELS PROPANE • By-Product of Natural Gas • Compressed at high pressure to liquefy • Domestic Fuel Source • Great for: • School Busses • Step Vans • Larger Vans • Mid-Sized Vehicles COMPRESSED NATURAL GAS (CNG) • Predominately Methane • Uses existing pipeline distribution system to deliver gas • Good for: • Heavy-Duty Trucks • Passenger cars • School Buses • Waste Management Trucks • DNREC trucks PROPANE AND CNG INFRASTRUCTURE • 8 Propane Autogas Stations • 1 CNG Station • Fleet and Public Access with accounts ELECTRIC VEHICLES • Electricity is considered an alternative fuel • Uses electricity from a power source and stores it in batteries • Two types: • Battery Electric • Plug-in Hybrid • Great for: • Passenger Vehicles EV INFRASTRUCTURE • 61 charging stations in Delaware • At 26 locations • 37,000 Charging Stations in the United States • Three types: • Level 1 • Level 2 • D.C. Fast Charging TYPES OF CHARGING STATIONS Charger Current Type Voltage (V) Charging Primary Use Time Level 1 Alternating 120 V 2 to 5 miles Current (AC) per hour of Residential charge Level 2 AC 240 V 10 to 20 miles Residential per hour of and charge Commercial DC Fast Direct Current 480 V 60 to 80 miles (DC) per 20 min. -

Comparison of Hydrogen Powertrains with the Battery Powered Electric Vehicle and Investigation of Small-Scale Local Hydrogen Production Using Renewable Energy

Review Comparison of Hydrogen Powertrains with the Battery Powered Electric Vehicle and Investigation of Small-Scale Local Hydrogen Production Using Renewable Energy Michael Handwerker 1,2,*, Jörg Wellnitz 1,2 and Hormoz Marzbani 2 1 Faculty of Mechanical Engineering, University of Applied Sciences Ingolstadt, Esplanade 10, 85049 Ingolstadt, Germany; [email protected] 2 Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology, School of Engineering, Plenty Road, Bundoora, VIC 3083, Australia; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Climate change is one of the major problems that people face in this century, with fossil fuel combustion engines being huge contributors. Currently, the battery powered electric vehicle is considered the predecessor, while hydrogen vehicles only have an insignificant market share. To evaluate if this is justified, different hydrogen power train technologies are analyzed and compared to the battery powered electric vehicle. Even though most research focuses on the hydrogen fuel cells, it is shown that, despite the lower efficiency, the often-neglected hydrogen combustion engine could be the right solution for transitioning away from fossil fuels. This is mainly due to the lower costs and possibility of the use of existing manufacturing infrastructure. To achieve a similar level of refueling comfort as with the battery powered electric vehicle, the economic and technological aspects of the local small-scale hydrogen production are being investigated. Due to the low efficiency Citation: Handwerker, M.; Wellnitz, and high prices for the required components, this domestically produced hydrogen cannot compete J.; Marzbani, H. Comparison of with hydrogen produced from fossil fuels on a larger scale. -

Understanding Long-Term Evolving Patterns of Shared Electric

Experience: Understanding Long-Term Evolving Patterns of Shared Electric Vehicle Networks∗ Guang Wang Xiuyuan Chen Fan Zhang Rutgers University Rutgers University Shenzhen Institutes of Advanced [email protected] [email protected] Technology, CAS [email protected] Yang Wang Desheng Zhang University of Science and Rutgers University Technology of China [email protected] [email protected] ABSTRACT CCS CONCEPTS Due to the ever-growing concerns on the air pollution and • Networks → Network measurement; Mobile networks; energy security, many cities have started to update their Cyber-physical networks. taxi fleets with electric ones. Although environmentally friendly, the rapid promotion of electric taxis raises prob- KEYWORDS lems to both taxi drivers and governments, e.g., prolonged Electric vehicle; mobility pattern; charging pattern; evolving waiting/charging time, unbalanced utilization of charging experience; shared autonomous vehicle infrastructures and reduced taxi supply due to the long charg- ing time. In this paper, we make the first effort to understand ACM Reference Format: the long-term evolving patterns through a five-year study Guang Wang, Xiuyuan Chen, Fan Zhang, Yang Wang, and Desh- on one of the largest electric taxi networks in the world, i.e., eng Zhang. 2019. Experience: Understanding Long-Term Evolving the Shenzhen electric taxi network in China. In particular, Patterns of Shared Electric Vehicle Networks. In The 25th Annual we perform a comprehensive measurement investigation International Conference on Mobile Computing and Networking (Mo- called ePat to explore the evolving mobility and charging biCom ’19), October 21–25, 2019, Los Cabos, Mexico. ACM, New York, patterns of electric vehicles. -

How Practical Are Alternative Fuel Vehicles?

How Practical Are Alternative Fuel Vehicles? Many of us have likely considered an alternative fuel vehicle at some point in our lives. Balancing the positives and negatives is a tricky process and varies greatly based on our personal situations. However, many of the negatives that previously created hesitancy have changed in recent years. Below, we have outlined a few of the most commonly mentioned negatives regarding the two leading alternative fuel vehicle types: Flex Fuel vehicles and Electric/Hybrid vehicles. Then, you can decide for yourself whether one of these vehicle types are practical for you! Cost – How much does the vehicle cost to purchase and operate? Flex Fuel: Flex Fuel vehicles typically cost about the same as a gasoline vehicle.1 For fuel cost, E85 typically costs slightly less than gasoline, however, due to decreased efficiency has a slightly higher cost per mile than gasoline.2 Overall, a Flex Fuel vehicle is likely to be slightly more expensive than a gasoline counterpart. Electric/Hybrid: This situation varies quite a bit depending on where you live. Electric vehicles and hybrid vehicles often cost considerably more than a conventional gasoline vehicle. For example, a plug-in hybrid will cost around $4000-$8000 more than a conventional model.3 However, there are federal rebates and local rebates that can refund thousands of dollars from the purchase price. Electric/Hybrid vehicles also tend to save money on fuel, with the possibility of saving thousands of dollars over the lifetime of the vehicle.4 Whether these rebates and fuel cost savings will eventually account for the higher purchase price can be estimated with comparison tools. -

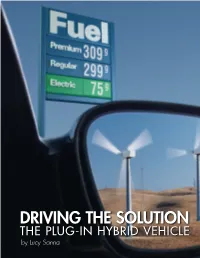

EPRI Journal--Driving the Solution: the Plug-In Hybrid Vehicle

DRIVING THE SOLUTION THE PLUG-IN HYBRID VEHICLE by Lucy Sanna The Story in Brief As automakers gear up to satisfy a growing market for fuel-efficient hybrid electric vehicles, the next- generation hybrid is already cruis- ing city streets, and it can literally run on empty. The plug-in hybrid charges directly from the electricity grid, but unlike its electric vehicle brethren, it sports a liquid fuel tank for unlimited driving range. The technology is here, the electricity infrastructure is in place, and the plug-in hybrid offers a key to replacing foreign oil with domestic resources for energy indepen- dence, reduced CO2 emissions, and lower fuel costs. DRIVING THE SOLUTION THE PLUG-IN HYBRID VEHICLE by Lucy Sanna n November 2005, the first few proto vide a variety of battery options tailored 2004, more than half of which came from Itype plugin hybrid electric vehicles to specific applications—vehicles that can imports. (PHEVs) will roll onto the streets of New run 20, 30, or even more electric miles.” With growing global demand, particu York City, Kansas City, and Los Angeles Until recently, however, even those larly from China and India, the price of a to demonstrate plugin hybrid technology automakers engaged in conventional barrel of oil is climbing at an unprece in varied environments. Like hybrid vehi hybrid technology have been reluctant to dented rate. The added cost and vulnera cles on the market today, the plugin embrace the PHEV, despite growing rec bility of relying on a strategic energy hybrid uses battery power to supplement ognition of the vehicle’s potential. -

A Review of Range Extenders in Battery Electric Vehicles: Current Progress and Future Perspectives

Review A Review of Range Extenders in Battery Electric Vehicles: Current Progress and Future Perspectives Manh-Kien Tran 1,* , Asad Bhatti 2, Reid Vrolyk 1, Derek Wong 1 , Satyam Panchal 2 , Michael Fowler 1 and Roydon Fraser 2 1 Department of Chemical Engineering, University of Waterloo, 200 University Avenue West, Waterloo, ON N2L3G1, Canada; [email protected] (R.V.); [email protected] (D.W.); [email protected] (M.F.) 2 Department of Mechanical and Mechatronics Engineering, University of Waterloo, 200 University Avenue West, Waterloo, ON N2L3G1, Canada; [email protected] (A.B.); [email protected] (S.P.); [email protected] (R.F.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-519-880-6108 Abstract: Emissions from the transportation sector are significant contributors to climate change and health problems because of the common use of gasoline vehicles. Countries in the world are attempting to transition away from gasoline vehicles and to electric vehicles (EVs), in order to reduce emissions. However, there are several practical limitations with EVs, one of which is the “range anxiety” issue, due to the lack of charging infrastructure, the high cost of long-ranged EVs, and the limited range of affordable EVs. One potential solution to the range anxiety problem is the use of range extenders, to extend the driving range of EVs while optimizing the costs and performance of the vehicles. This paper provides a comprehensive review of different types of EV range extending technologies, including internal combustion engines, free-piston linear generators, fuel cells, micro Citation: Tran, M.-K.; Bhatti, A.; gas turbines, and zinc-air batteries, outlining their definitions, working mechanisms, and some recent Vrolyk, R.; Wong, D.; Panchal, S.; Fowler, M.; Fraser, R. -

The Future of Transportation Alternative Fuel Vehicle Policies in China and United States

Clark University Clark Digital Commons International Development, Community and Master’s Papers Environment (IDCE) 12-2016 The uturF e of Transportation Alternative Fuel Vehicle Policies In China and United States JIyi Lai [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.clarku.edu/idce_masters_papers Part of the Environmental Studies Commons Recommended Citation Lai, JIyi, "The uturF e of Transportation Alternative Fuel Vehicle Policies In China and United States" (2016). International Development, Community and Environment (IDCE). 163. https://commons.clarku.edu/idce_masters_papers/163 This Research Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Master’s Papers at Clark Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in International Development, Community and Environment (IDCE) by an authorized administrator of Clark Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. The Future of Transportation Alternative Fuel Vehicle Policies In China and United States Jiyi Lai DECEMBER 2016 A Masters Paper Submitted to the faculty of Clark University, Worcester, Massachusetts, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the department of IDCE And accepted on the recommendation of ! Christopher Van Atten, Chief Instructor ABSTRACT The Future of Transportation Alternative Fuel Vehicle Policies In China and United States Jiyi Lai The number of passenger cars in use worldwide has been steadily increasing. This has led to an increase in greenhouse gas emissions and other air pollutants, and new efforts to develop alternative fuel vehicles to mitigate reliance on petroleum. Alternative fuel vehicles include a wide range of technologies powered by energy sources other than gasoline or diesel fuel. -

Powering the U.S. Army of the Future Overall Objective

Powering the U.S. Army of the Future Overall Objective A study to find out what are the emerging technology options in energy/ power to best suit the Army's operational requirements in 2035 and beyond. This entails bringing sufficient energy to the field and conserving its use while maintaining or enhancing the Army’s warfighting capabilities. Download the report at: http://nap.edu/26052 Duo-Fold Focus Approach Overall Study Objectives Source: Project Pele Overview, Mobile Nuclear Power for Future DoD Needs, March 2020, Office of the Secretary of the Defense; Strategic Capabilities Office Previous Studies Advocating Nuclear Power and Battery Electric Vehicles Employment of mobile nuclear power is consistent with the new geopolitical landscape and priorities outlined in the US National Security Strategy (NSS) and the 2018 National Defense Strategy focusing on China and Russia as the principal priorities for the U.S. Department of Defense (DOD)… This study finds that as a technical matter, nuclear power can reduce supply vulnerabilities and operating costs while providing a sustainable option for reducing petroleum demand and focusing fuel forward to support Combatant Commander (CCDR) priorities and maneuver in multi-domain operations (MDO). Study on the Use of Mobile Nuclear Plants Deputy Chief of Staff, G-4 October 26, 2018 “Powering the Army of 2035” In One Slide • There are many realistic opportunities to reduce fuel transported to the field by up to 1/3. Liquid hydrocarbon fuels will remain the main source of combined energy and power brought to the battlefield through 2035. • Electrification of ground combat vehicles is highly desirable, but it should take the form of hybrid electric vehicles (with internal combustion engines), not all battery electric vehicles. -

Clean Cities Overview

MASSACHUSETTS CLEAN CITIES COALITION Energy Boot Camp Presenter Stephen Russell September 4, 2014 [email protected] Clean Cities / 1 Creating A Greener Energy Future For the Commonwealth The alternative transportation/ Massachusetts Clean Cities Coalition are are part of the Department of Energy Resources Renewables Division Coordinators: Stephen Russell and Michelle Broussard EVs Biodiesel Natural gas Clean Cities / 2 Clean Cities Clean Cities’ Mission To advance the energy, economic, and environmental security of the U.S. by supporting local decisions to adopt practices that contribute to the reduction of petroleum consumption in the transportation sector. • Sponsored by the DOE’s Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy's Vehicle Technologies program • Provides a framework for businesses and governments to work together as a coalition to enhance markets • Coordinate activities, identify mutual interests, develop regional economic opportunities, and improve air quality Clean Cities / 3 Clean Cities Today • 90 active coalitions in 45 states • 775,000 AFVs using alternative fuels • 6,600 AFV stations • 8,400+ stakeholders Clean Cities / 4 MCCC Vision • Clean Cities are a resource to both public and private fleets. • They are a catalyst to match fleets with resources needed. • They are the the go-to folks for technical resources for alternative fuels and technologies. 5 Clean Cities / 5 Clean Cities portfolio of alternative fuels Alternative Fuels Biodiesel (B100) Electricity Ethanol (E85) Hydrogen Natural gas Propane Fuel Blends – commonly used Biodiesel/diesel blends (B2, B5, B20) Ethanol/gasoline blends (E10) Hydrogen/natural gas blends (HCNG) Diesel/CNG 6 Clean Cities / 6 How do I choose a fuel •CNG Cleaner Less $ alternative to Diesel fuel.