How to Reach the Upper Tigris: the Route Through the Tur Abdin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mesopotamia-Ancient-Civilizations

Published in 2012 by Britannica Educational Publishing (a trademark of Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.) in association with Rosen Educational Services, LLC 29 East 21st Street, New York, NY 10010. Copyright © 2012 Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, and the Thistle logo are registered trademarks of Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. All rights reserved. Rosen Educational Services materials copyright © 2012 Rosen Educational Services, LLC. All rights reserved. Distributed exclusively by Rosen Educational Services. For a listing of additional Britannica Educational Publishing titles, call toll free (800) 237-9932. First Edition Britannica Educational Publishing Michael I. Levy: Executive Editor, Encyclopædia Britannica J.E. Luebering: Director, Core Reference Group, Encyclopædia Britannica Adam Augustyn: Assistant Manager, Encyclopædia Britannica Anthony L. Green: Editor, Compton’s by Britannica Michael Anderson: Senior Editor, Compton’s by Britannica Sherman Hollar: Associate Editor, Compton’s by Britannica Marilyn L. Barton: Senior Coordinator, Production Control Steven Bosco: Director, Editorial Technologies Lisa S. Braucher: Senior Producer and Data Editor Yvette Charboneau: Senior Copy Editor Kathy Nakamura: Manager, Media Acquisition Rosen Educational Services Alexandra Hanson-Harding: Editor Nelson Sá: Art Director Cindy Reiman: Photography Manager Matthew Cauli: Designer, Cover Design Introduction by Alexandra Hanson-Harding Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Mesopotamia / edited by Sherman Hollar.—1st ed. p. cm.—(Ancient civilizations) “In association with Britannica Educational Publishing, Rosen Educational Services.” Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-61530-575-9 (eBook) 1. Iraq—Civilization—To 634—Juvenile literature. I. Hollar, Sherman. DS71.M545 2011 935—dc22 2011007580 On the cover, page 3: An copy of a vintage photo of a winged human-headed bull from the Palace of King Sargon II, in what is now Khorsabad, Iraq. -

Downloadable Reproducible Ebooks Sample Pages

Downloadable Reproducible eBooks Sample Pages These sample pages from this eBook are provided for evaluation purposes. The entire eBook is available for purchase at www.socialstudies.com or www.writingco.com. To browse more eBook titles, visit http://www.socialstudies.com/ebooks.html To learn more about eBooks, visit our help page at http://www.socialstudies.com/ebookshelp.html For questions, please e-mail [email protected] To learn about new eBook and print titles, professional development resources, and catalogs in the mail, sign up for our monthly e-mail newsletter at http://socialstudies.com/newsletter/ Copyright notice: Copying of the book or its parts for resale is prohibited. Additional restrictions may be set by the publisher. Ancient Mesopotamia & Ancient India Mr. Donn and Maxie’s Always Something You Can Use Series Lin & Don Donn, Writers Bill Williams, Editor Dr. Aaron Willis, Project Coordinator Jonathan English, Editorial Assistant Social Studies School Service 10200 Jefferson Blvd., P.O. Box 802 Culver City, CA 90232 http://socialstudies.com [email protected] (800) 421-4246 © 2004 Social Studies School Service 10200 Jefferson Blvd., P.O. Box 802 Culver City, CA 90232 United States of America (310) 839-2436 (800) 421-4246 Fax: (800) 944-5432 Fax: (310) 839-2249 http://socialstudies.com [email protected] Permission is granted to reproduce individual worksheets for classroom use only. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 1-56004-166-8 Product Code: ZP575 iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Ancient Mesopotamia Introduction .................................................................................................... 1 Sections: 1. Geography of Ancient Mesopotamia ...................................................................................... 3 Unlabeled Map of Ancient Mesopotamia.................................................................................... 5 Labeled Map of Ancient Mesopotamia ...................................................................................... -

Grade 6 Social Studies 2019-2020

Social Studies Review Directions: Grade 6 1. Watch CNN 10 every day and complete the CNN 10 Template located on page 58.You complete a paper copy or do one digitally and turn it in via Google Classroom. 2. Read through the notes then complete the Student Review Activity for each Unit. You can also use information from the Techbook or look through the classroom handouts to help you complete this activity. You complete a paper copy or do one digitally and turn it in via Google 6 Classroom. 3. If you finish numbers 1 and 2, watch the Unit Review Videos on the Techbook and write a summary on each one. Social Studies Useful Links 2019-2020 Email: [email protected] Google Classroom Code: sc7ccth Techbook: (Email me if you forget the password) https://elmsscobbie6.weebly.com/ CNN 10: https://www.cnn.com/cnn10 Public Schools of Review Videos: (Email me if you forget North Carolina the password) https://elmsscobbie6.weebly.com/uni State Board of t-reviews.html Education Department of Public Instruction Raleigh, North Carolina 27699- 6314 Table of Content Essential Questions Unit 1: Geography (Pages 3-6) Unit 6: The Roman Republic and Empire (Pages 30-36) 1.1 What is geography and how can it help us to understand the world? 6.1 How did geography and trade routes impact the growth of Rome? 1.2 How can the five themes of geography be used to show the relationship 6.2 Was the Roman Republic democratic? between people and places? Why do geographers use a variety of maps to 6.3 How did Rome's transition from Republic to Empire impact its -

Chapter 1: the First Civilizations

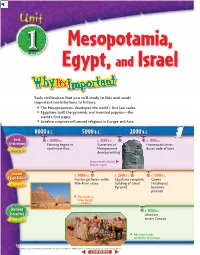

Mesopotamia, Egypt, and Israel Each civilization that you will study in this unit made important contributions to history. • The Mesopotamians developed the world’s first law codes. • Egyptians built the pyramids and invented papyrus—the world’s first paper. • Israelite scripture influenced religions in Europe and Asia. 80008000 B..C.. 5000 B..C.2.2000 B..C.. FirstFirst c. 8000 B.C. c. 3200 B.C. c. 1790 B.C. CivilizationsCivilizations Farming begins in Sumerians in Hammurabi intro- southwest Asia Mesopotamia duces code of laws C 1 hapter develop writing Hammurabi stands before a god Ancient c. 5000 B.C. c. 2540 B.C. c. 1500 B.C. Egypt & Kush Hunter-gatherers settle Egyptians complete Queen Nile River valley building of Great Hatshepsut C hapter 2 Pyramid becomes pharaoh Pyramids at Giza, Egypt c. 2540 B.C. AncientAncient c. 1800 B.C. IsraelitesIsraelites Abraham enters Canaan Chapter 3 Abraham leads Israelites to Canaan 114 (t)Reunion des Musees Nationaux/Art Resource, NY, (c)John Heaton/CORBIS, (b)Tom Lovell/National Geographic Society Image Collection ers)SuperStock ° ° ° ° 0 0 1,000 mi. 30 E Caspian Sea 60 E 90 E 0 1,000 km ASIA Mercator projection Black Sea Chapter 1 T i g r i Chapter 3 s Chapter 3 E u R s ph du R r . In . at es R . 30°N N Persian W E . Gulf Chapter 2 R e l S i N Red Sea Chapter 1 Chapter 2 Chapter 3 AFRICA EQUATOR INDIAN (tl)Brooklyn Museum of Art, New York/Charles Edwin Wilbour Fund/Bridgeman Art Library, (bl)Erich Lessing/Art Resource, NY, (oth NY, (bl)Erich Lessing/Art Resource, Edwin Wilbour Fund/Bridgeman Art Library, Museum of Art, New York/Charles (tl)Brooklyn OCEAN 10001000 B..C.7.750 B..C. -

The Geography of Mesopotamia E.Q. Why Did People Settle In

The Geographyof Mesopotamia E.Q. Why did peoplesettle in Mesopotamiaand what weie advantagesand disadvantages did its geography provide to the peoplethat settled there? The Tigris andEuphrates rivers startin southwestAsia. They begin in the mountainsof what are now Turkey andKurdistan. From therethey flow throughwhat is now Iraq to the PersianGulf. It is in this areathat one of the first civilizationswas formed. The region aroundwhere the rivers flow is calledMesopotamia. In fact,the name means "land betweenthe rivers". This landis borderedby the PersianGulf to the southeast.The Syrianand Arabian Desertsstretch west to the Red Sea. The ZagrosMountains border this areato the eastand stretchnorthward. The MediterraneanSea is the largebody of waterto the west. The Tigris andEuphrates rivers providedwater and ameansof transportationfor the peoplewho settledin the area.In ancienttimes, it was easierto travel by boatthan over land. Few roads existedduring this time.Also, becauseof the rivers,this areahad arich supplyof fish and waterfowlthat couldbe usedfor food. The land in this areawas flat andfertile, rich in nutrients. This is causedby the flooding of the rivers. Almost yearly, rain andmelting snowin the mountainscaused the rivers to swell. As the water flowed down the mountains,it pickedup soil. When the rivers reachedthe plains,water overflowedonto the floodplain,the flat land borderingthe banks. As the water spreadover the floodplain,the soil it carriedsettled on the land. The fine soil depositedby riversis calledsilt. Silt is fertile andgood for growingcrops. Because of this,Mesopotamia is alsoknown as"The Fertile Crescenttt. Usually,less than 10 inchesof rain fell in Mesopotamiaeach year. Summerswere hot. This type of climateis calledsemiarid. Althoughit washot anddry, ancientpeople could still grow crops becauseof the riversand fertile soil. -

Grade 6 Social Studies

Grade 6 Social Studies: Year-Long Overview To be productive members of society, students must be critical consumers of information they read, hear, and observe and communicate effectively about their ideas. They need to gain knowledge from a wide array of sources and examine and evaluate that information to develop and express an informed opinion, using information gained from the sources and their background knowledge. Students must also make connections between what they learn about the past and the present to understand how and why events happen and people act in certain ways. To accomplish this, students must: 1. Use sources regularly to learn content. 2. Make connections among people, events, and ideas across time and place. 3. Express informed opinions using evidence from sources and outside knowledge. Teachers must create instructional opportunities that delve deeply into content and guide students in developing and supporting claims about social studies concepts. In grade 6, students explore the factors that influence how civilizations develop as well as what contributes to their decline as they learn about early humans and the first permanent settlements, the ancient river valley civilizations, Greek and Roman civilizations, Asian and African civilizations, Medieval Europe, and the Renaissance (aligned to grade 6 GLEs). A S O N D J F M A M Grade 6 Content u e c o e a e a p a g p t v c n b r r y t How do environmental Early Humans: Survival and changes impact human life and X X Settlement settlement? How do geography and The Ancient -

Chapter 3, Lesson 1 Geography of Mesopotamia TERMS and NAMES Terms Definition Importance

Name:___________________________________________ Date:_________________ Chapter 3, Lesson 1 Geography of Mesopotamia TERMS AND NAMES Terms Definition Importance Mesopotamia The region between the Tigris and Geography Theme—civilizations Euphrates Rivers arise in geographic locations that help the development of agriculture and /or trade floodplain That flat land bordering a river Rich soil was spread farther as silt from the river traveled in water silt Fine soil deposited by rivers This soil made is possible to grow so many different crops well semiarid Region having little rainfall and Type of geography or region warm temperatures affects the ability of humans to survive in a particular place drought Period without enough rain or Lack of rain can affect the growth snow fall of crops and how much people can eat in a year surplus An amount of a good (such as Surpluses allow for less intensity in food) that is in excess (extra) from farming, more people can eat and what is needed remain healthy, more diverse skills MAIN IDEAS 1. How did the land between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers support agriculture? The rivers flood each year and deposit rich fertile soil on the surrounding land. The rivers also provided water for crops. 2. How did the climate of Mesopotamia likely affect early farmers’ decisions about where to settle and build farming villages? If farmers were close to the rivers, they had the risk of the crops being destroyed by floods, but if they lived too far from the river, they did have enough water and their crops would die/wilt. Name:___________________________________________ Date:_________________ 3. -

02 CH02 P020-047.Qxp 6/10/09 13:56 Page 20 02 CH02 P020-047.Qxp 6/10/09 13:56 Page 21 CHAPTER 2 Ancient Near Eastern Art

02_CH02_P020-047.qxp 6/10/09 13:56 Page 20 02_CH02_P020-047.qxp 6/10/09 13:56 Page 21 CHAPTER 2 Ancient Near Eastern Art ROWING AND STORING CROPS AND RAISING ANIMALS FOR FOOD, the signature accomplishments of Neolithic peoples, would gradually change the course of civilization. Not long before they ceased to follow Gwild animal herds and gather food to survive, people began to form permanent settlements. By the end of the Neolithic era, these settlements grew beyond the bounds of the village into urban centers. In the fourth earliest writing system, beginning around 3400–3200 bce, con- millennium bce, large-scale urban communities of as many as sisting of pictograms pressed into clay with a stylus to create 40,000 people began to emerge in Mesopotamia, the land between inventories. By around 2900 bce, the Mesopotamians had refined the Tigris and Euphrates rivers. The development of cities had the pictograms into a series of wedge-shaped signs known as tremendous ramifications for the development of human life and cuneiform (from cuneus, Latin for “wedge”). They used this sys- for works of art. tem for administrative accounts and the Sumerian Epic of Although today the region of Mesopotamia is largely an arid Gilgamesh in the late third millennium bce. Cuneiform writing plain, written, archaeological, and artistic evidence indicates that continued through much of the ancient era in the Near East and at the dawn of civilization lush vegetation covered it. By master- formed a cultural link between diverse groups who established ing irrigation techniques, populations there exploited the rivers power in the region. -

Grade 6: Unit 2

Social Studies Curriculum Grade 6: Unit 2 1 Course Description The goal for 6th grade World History I students is to refresh their knowledge and understanding of fundamental geography concepts. Students will also need to acquire the core analytical skills necessary to apply the methods of historical inquiry using primary and secondary sources. With these fundamentals in place students will study the political, economic, cultural, religious, and technological changes that occurred in the ancient world. Units will include: prehistory and early man through the Neolithic Era, Ancient Mesopotamia and Egypt, who are considered to be amongst the world’s earliest river civilizations, and lastly Ancient Greece and the Roman Empire, who are thought to have greatly influenced Western civilization. 2 Pacing Guide Unit Topic Suggested Timing Unit 1 World Geography and Human Origins 7 Unit 2 Mesopotamia and the Fertile Crescent 7 Unit 3 Ancient Egypt, Kush and Phoenicia 7 Unit 4 Ancient Greece 7 Unit 5 Ancient Roman Republic and Empire 8 3 Educational Technology Standards 8.1.8.A.2, 8.1.8.A.3, 8.1.8.B.1, 8.1.8.D.2 Technology Operations and Concepts Create a document using one or more digital applications to be critiqued by professionals for usability. Example of Use: Using digital tools create a map of the Fertile Crescent. Use and/or develop a simulation that provides an environment to solve a real world problem or theory. Example of Use: Political and Historical Maps: Use digital maps to label important modern and historical areas in Middle East region. Creativity and Innovation Synthesize and publish information about a local or global issue or event. -

Early River Valley Civilizations: Mesopotamia

Early River Valley Civilizations: Mesopotamia Mesopotamia Map Partner Discussion Question • Why did humans travel around? What was the one thing they HAD to have? Because of this need, where do we find most of our early villages and cities located? The Start of Mesopotamia • Middle East (5000 BCE) – Fertile Crescent • Fertile due to: – 2 major rivers that emptied into the Persian Gulf • Tigris River • Euphrates River – What country is this area today??? • Mesopotamia (c. 3100-529 BCE) – Greek term meaning “between the rivers” • Small cities close to Persian Gulf – Later spread further WHY??? Geography of Mesopotamia Geography Practice: Fertile Crescent Impact of Geography • Rivers –Positives • Fertile land allowed crops to grow • Deposited silt –Rich soil from bottom of riverbeds Impact of Geography – Negatives • Rivers flooded unpredictably • Area of Sumer was small • Lacked other vital natural resources –How would they get these??? Partner Discussion Question • What technology did the Sumerians utilize that would help lessen the negative consequences of their location? Impact of Geography • Problem Solving – New technologies • Irrigation canals – Control water – Spread the amount of farmable land Impact of Geography • Built walls to protect the cities from invaders Impact of Geography • Traded for resources – Who did they trade with??? What do you think they traded??? – Traded grain and cloth for wood, metal, and tools Mesopotamia – First Civilization • Sumer (2900 BCE) – City-states – Considered FIRST civilization Partner Discussion -

Hamish Cameron, Making Mesopotamia: Geography and Empire in a Romano-Iranian Borderland (Impact of Empire – 32), Brill, Leiden–Boston 2019, 375 Pp

ELECTRUM * Vol. 27 (2020): 263–265 doi:10.4467/20800909EL.20.024.12814 www.ejournals.eu/electrum Hamish Cameron, Making Mesopotamia: Geography and Empire in a Romano-Iranian Borderland (Impact of Empire – 32), Brill, Leiden–Boston 2019, 375 pp. + 27 maps; ISSN 1572-0500; ISBN 978-90-04-38862-8 One might expect that the Romans would have had extensive knowledge of the physical, political and cultural geography of Mesopotamia. After all, for many centuries Rome neighboured with the Parthian state governed by the Arsacid dynasty, and during numer- ous conflicts between the two states the Roman armies frequently invaded Mesopotamia, sometimes incurring as far as the waters of the Persian Gulf. The information obtained through diplomatic contacts, and in particular during military actions, should therefore have been present in Roman historical and geographical literature, since reports of some campaigns against the Parthians were widely publicised for propaganda purposes by contemporary authors, who were either participants in the events themselves, or wrote about their protagonists. In his book Making Mesopotamia: Geography and Empire in a Romano-Iranian Borderland, Hamish Cameron attempts to prove that this issue is much more complex, presenting his own ideas on the extent of the Romans’ knowledge about the region at various times. Cameron sets himself the task of finding the answer to a series of questions: “how did the Romans imagine the Mesopotamian Borderland? How did they represent the physical reality of this geopolitical space in words? What did they choose to describe, to emphasise, to suggest, to omit? How did they construct their narratives to best explain, justify, rationalise or ignore this edge of Roman power? How did they make ‘Mesopo- tamia’?” (p. -

Of God(S), Trees, Kings, and Scholars

STUDIA ORIENTALIA PUBLISHED BY THE FINNISH ORIENTAL SOCIETY 106 OF GOD(S), TREES, KINGS, AND SCHOLARS Neo-Assyrian and Related Studies in Honour of Simo Parpola Edited by Mikko Luukko, Saana Svärd and Raija Mattila HELSINKI 2009 OF GOD(S), TREES, KINGS AND SCHOLARS clay or on a writing board and the other probably in Aramaic onleather in andtheotherprobably clay oronawritingboard ME FRONTISPIECE 118882. Assyrian officialandtwoscribes;oneiswritingincuneiformo . n COURTESY TRUSTEES OF T H E BRITIS H MUSEUM STUDIA ORIENTALIA PUBLISHED BY THE FINNISH ORIENTAL SOCIETY Vol. 106 OF GOD(S), TREES, KINGS, AND SCHOLARS Neo-Assyrian and Related Studies in Honour of Simo Parpola Edited by Mikko Luukko, Saana Svärd and Raija Mattila Helsinki 2009 Of God(s), Trees, Kings, and Scholars: Neo-Assyrian and Related Studies in Honour of Simo Parpola Studia Orientalia, Vol. 106. 2009. Copyright © 2009 by the Finnish Oriental Society, Societas Orientalis Fennica, c/o Institute for Asian and African Studies P.O.Box 59 (Unioninkatu 38 B) FIN-00014 University of Helsinki F i n l a n d Editorial Board Lotta Aunio (African Studies) Jaakko Hämeen-Anttila (Arabic and Islamic Studies) Tapani Harviainen (Semitic Studies) Arvi Hurskainen (African Studies) Juha Janhunen (Altaic and East Asian Studies) Hannu Juusola (Semitic Studies) Klaus Karttunen (South Asian Studies) Kaj Öhrnberg (Librarian of the Society) Heikki Palva (Arabic Linguistics) Asko Parpola (South Asian Studies) Simo Parpola (Assyriology) Rein Raud (Japanese Studies) Saana Svärd (Secretary of the Society)