TULAREMIA Bioterrorism Agent Profiles for Health Care Workers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tick-Borne Diseases in Maine a Physician’S Reference Manual Deer Tick Dog Tick Lonestar Tick (CDC Photo)

tick-borne diseases in Maine A Physician’s Reference Manual Deer Tick Dog Tick Lonestar Tick (CDC PHOTO) Nymph Nymph Nymph Adult Male Adult Male Adult Male Adult Female Adult Female Adult Female images not to scale know your ticks Ticks are generally found in brushy or wooded areas, near the DEER TICK DOG TICK LONESTAR TICK Ixodes scapularis Dermacentor variabilis Amblyomma americanum ground; they cannot jump or fly. Ticks are attracted to a variety (also called blacklegged tick) (also called wood tick) of host factors including body heat and carbon dioxide. They will Diseases Diseases Diseases transfer to a potential host when one brushes directly against Lyme disease, Rocky Mountain spotted Ehrlichiosis anaplasmosis, babesiosis fever and tularemia them and then seek a site for attachment. What bites What bites What bites Nymph and adult females Nymph and adult females Adult females When When When April through September in Anytime temperatures are April through August New England, year-round in above freezing, greatest Southern U.S. Coloring risk is spring through fall Adult females have a dark Coloring Coloring brown body with whitish Adult females have a brown Adult females have a markings on its hood body with a white spot on reddish-brown tear shaped the hood Size: body with dark brown hood Unfed Adults: Size: Size: Watermelon seed Nymphs: Poppy seed Nymphs: Poppy seed Unfed Adults: Sesame seed Unfed Adults: Sesame seed suMMer fever algorithM ALGORITHM FOR DIFFERENTIATING TICK-BORNE DISEASES IN MAINE Patient resides, works, or recreates in an area likely to have ticks and is exhibiting fever, This algorithm is intended for use as a general guide when pursuing a diagnosis. -

Antigen Detection Assay for the Diagnosis of Melioidosis

PI: Title: Antigen Detection assay for the Diagnosis of Melioidosis Received: 12/05/2013 FOA: PA10-124 Council: 05/2014 Competition ID: ADOBE-FORMS-B1 FOA Title: NIAID ADVANCED TECHNOLOGY STTR (NIAID-AT-STTR [R41/R42]) 2 R42 AI102482-03 Dual: Accession Number: 3650491 IPF: 3966401 Organization: INBIOS INTERNATIONAL, INC. Former Number: Department: IRG/SRG: ZRG1 IDM-V (12)B AIDS: N Expedited: N Subtotal Direct Costs Animals: N New Investigator: N (excludes consortium F&A) Humans: Y Early Stage Investigator: N Year 3: Clinical Trial: N Year 4: Current HS Code: E4 Year 5: HESC: N Senior/Key Personnel: Organization: Role Category: Always follow your funding opportunity's instructions for application format. Although this application demonstrates good grantsmanship, time has passed since the grantee applied. The sample may not reflect the latest format or rules. NIAID posts new samples periodically: https://www.niaid.nih.gov/grants-contracts/sample-applications The text of the application is copyrighted. You may use it only for nonprofit educational purposes provided the document remains unchanged and the PI, the grantee organization, and NIAID are credited. Note on Section 508 conformance and accessibility: We have reformatted these samples to improve accessibility for people with disabilities and users of assistive technology. If you have trouble accessing the content, please contact the NIAID Office of Knowledge and Educational Resources at [email protected]. Additions for Review Accepted Publication Accepted manuscript news Post-submission supplemental material. Information about manuscript accepted for publication. OMB Number: 4040-0001 Expiration Date: 06/30/2011 APPLICATION FOR FEDERAL ASSISTANCE 3. DATE RECEIVED BY STATE State Application Identifier SF 424 (R&R) 1. -

Tick-Borne Disease Working Group 2020 Report to Congress

2nd Report Supported by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services • Office of the Assistant Secretary for Health Tick-Borne Disease Working Group 2020 Report to Congress Information and opinions in this report do not necessarily reflect the opinions of each member of the Working Group, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, or any other component of the Federal government. Table of Contents Executive Summary . .1 Chapter 4: Clinical Manifestations, Appendices . 114 Diagnosis, and Diagnostics . 28 Chapter 1: Background . 4 Appendix A. Tick-Borne Disease Congressional Action ................. 8 Chapter 5: Causes, Pathogenesis, Working Group .....................114 and Pathophysiology . 44 The Tick-Borne Disease Working Group . 8 Appendix B. Tick-Borne Disease Working Chapter 6: Treatment . 51 Group Subcommittees ...............117 Second Report: Focus and Structure . 8 Chapter 7: Clinician and Public Appendix C. Acronyms and Abbreviations 126 Chapter 2: Methods of the Education, Patient Access Working Group . .10 to Care . 59 Appendix D. 21st Century Cures Act ...128 Topic Development Briefs ............ 10 Chapter 8: Epidemiology and Appendix E. Working Group Charter. .131 Surveillance . 84 Subcommittees ..................... 10 Chapter 9: Federal Inventory . 93 Appendix F. Federal Inventory Survey . 136 Federal Inventory ....................11 Chapter 10: Public Input . 98 Appendix G. References .............149 Minority Responses ................. 13 Chapter 11: Looking Forward . .103 Chapter 3: Tick Biology, Conclusion . 112 Ecology, and Control . .14 Contributions U.S. Department of Health and Human Services James J. Berger, MS, MT(ASCP), SBB B. Kaye Hayes, MPA Working Group Members David Hughes Walker, MD (Co-Chair) Adalbeto Pérez de León, DVM, MS, PhD Leigh Ann Soltysiak, MS (Co-Chair) Kevin R. -

Reportable Diseases in Illinois

You are the front line. Help protect against disease outbreaks in Chicago. Per the Control of Communicable Disease Code of Illinois, it is the REPORTABLE responsibility of physicians, physician assistants, nurses, nurse aides or any other person having knowledge of any of the following diseases, DISEASES confirmed or suspected, to report the case to the Chicago Department IN ILLINOIS of Public Health (CDPH) within the timeframe indicated. Information reportable by law and allowed by HIPAA CFR 164 512(b) TO REPORT CASES: CALL 312-743-9000 OR after business hours. ASK for the CALL 311 communicable disease physician. IMMEDIATE (within 3 hours by phone) • Any unusual case or • Botulism, foodborne • Q-fever (if suspected to cluster of cases that may • Brucellosis (if suspected to be a bioterrorist event or indicate a public health be a part of a bioterrorist part of an outbreak) hazard (e.g. MERS-CoV, event or part of an • Smallpox Ebola Virus Disease, Acute outbreak) • Sever Acute Respiratory Flaccid Myelitis) • Diphtheria Syndrome (SARS) • Any suspected bioterrorism • Influenza A, variant • Tularemia (if suspected to threat or event • Plague be a bioterrorist event or • Anthrax • Poliomyelitis part of an outbreak) 24 HOURS (by phone or e-reporting) • Botulism: intestinal, wound, and other • Hepatitis A • Staphylococcus aureus, Methicillin • Brucellosis • Influenza-associated intensive care unit resistant (MRSA) 2 or more cases in a • Chickenpox (varicella) hospitalization community setting • Cholera (Vibrio cholera O1 or O139) • Measles -

Development of Diagnostic Assays for Melioidosis, Tularemia, Plague And

University of Nevada, Reno Development of Diagnostic Assays for Melioidosis, Tularemia, Plague and COVID19 A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Cellular and Molecular Biology By Derrick Hau Dr. David P. AuCoin / Dissertation Advisor December 2020 THE GRADUATE• SCHOOL We recommend that the dissertation prepared under our supervision by entitled be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Advisor Committee Member Committee Member Committee Member Graduate School Representative David W. Zeh, Ph.D., Dean Graduate School December 2020 i Abstract Infectious diseases are caused by pathogenic organisms which can be spread throughout communities by direct and indirect contact. Burkholderia pseudomallei, Francisella tularenisis, and Yersinia pestis are the causative agents of melioidosis, tularemia and plague, respectively. These bacteria pertain to the United States of America Federal Select Agent Program as they are associated with high mortality rates, lack of medical interventions and are potential agents of bioterrorism. The novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) has resulted in a global pandemic due to the highly infectious nature and elevated virulence of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). Proper diagnosis of these infections is warranted to administer appropriate medical care and minimize further spreading. Current practices of diagnosing melioidosis, tularemia, plague and COVID-19 are inadequate due to limited resources and the untimely nature of the techniques. Commonly, diagnosing an infectious disease is by the direct detection of the causative agent. Isolation by bacterial culture is the gold standard for melioidosis, tularemia and plague infections; detection of SAR-CoV-2 nucleic acid by real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) is the gold standard for diagnosing COVID-19. -

Tularemia (CFSPH)

Tularemia Importance Tularemia is a zoonotic bacterial disease with a wide host range. Infections are most prevalent among wild mammals and marsupials, with periodic epizootics in Rabbit Fever, lagomorphs and rodents, but clinical cases also occur in sheep, cats and other Deerfly Fever, domesticated species. A variety of syndromes can be seen, but fatal septicemia is Meat-Cutter’s Disease common in some species. In humans, tularemia varies from a localized infection to Ohara Disease, fulminant, life-threatening pneumonia or septicemia. Francis Disease Tularemia is mainly seen in the Northern Hemisphere, where it has recently emerged or re-emerged in some areas, including parts of Europe and the Middle East. A few endemic clinical cases have also been recognized in regions where this disease Last Updated: June 2017 was not thought to exist, such as Australia, South Korea and southern Sudan. In some cases, emergence may be due to increased awareness, surveillance and/or reporting requirements; in others, it has been associated with population explosions of animal reservoir hosts, or with social upheavals such as wars, where sanitation is difficult and infected rodents may contaminate food and water supplies. Occasionally, this disease may even be imported into a country in animals. In 2002, tularemia entered the Czech Republic in a shipment of sick pet prairie dogs from the U.S. Etiology Tularemia is caused by Francisella tularensis (formerly known as Pasteurella tularensis), a Gram negative coccobacillus in the family Francisellaceae and class γ- Proteobacteria. Depending on the author, either three or four subspecies are currently recognized. F. tularensis subsp. tularensis (also known as type A) and F. -

Tularemia – Epidemiology

This first edition of theWHO guidelines on tularaemia is the WHO GUIDELINES ON TULARAEMIA result of an international collaboration, initiated at a WHO meeting WHO GUIDELINES ON in Bath, UK in 2003. The target audience includes clinicians, laboratory personnel, public health workers, veterinarians, and any other person with an interest in zoonoses. Tularaemia Tularaemia is a bacterial zoonotic disease of the northern hemisphere. The bacterium (Francisella tularensis) is highly virulent for humans and a range of animals such as rodents, hares and rabbits. Humans can infect themselves by direct contact with infected animals, by arthropod bites, by ingestion of contaminated water or food, or by inhalation of infective aerosols. There is no human-to-human transmission. In addition to its natural occurrence, F. tularensis evokes great concern as a potential bioterrorism agent. F. tularensis subspecies tularensis is one of the most infectious pathogens known in human medicine. In order to avoid laboratory-associated infection, safety measures are needed and consequently, clinical laboratories do not generally accept specimens for culture. However, since clinical management of cases depends on early recognition, there is an urgent need for diagnostic services. The book provides background information on the disease, describes the current best practices for its diagnosis and treatment in humans, suggests measures to be taken in case of epidemics and provides guidance on how to handle F. tularensis in the laboratory. ISBN 978 92 4 154737 6 WHO EPIDEMIC AND PANDEMIC ALERT AND RESPONSE WHO Guidelines on Tularaemia EPIDEMIC AND PANDEMIC ALERT AND RESPONSE WHO Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data WHO Guidelines on Tularaemia. -

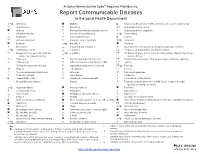

Report Communicable Diseases to the Local Health Department

Arizona Administrative Code Requires Providers to: Report Communicable Diseases to the Local Health Department *O Amebiasis Glanders O Respiratory disease in a health care institution or correctional facility Anaplasmosis Gonorrhea * Rubella (German measles) Anthrax Haemophilus influenzae, invasive disease Rubella syndrome, congenital Arboviral infection Hansen’s disease (Leprosy) *O Salmonellosis Babesiosis Hantavirus infection O Scabies Basidiobolomycosis Hemolytic uremic syndrome *O Shigellosis Botulism *O Hepatitis A Smallpox Brucellosis Hepatitis B and Hepatitis D Spotted fever rickettsiosis (e.g., Rocky Mountain spotted fever) *O Campylobacteriosis Hepatitis C Streptococcal group A infection, invasive disease Chagas infection and related disease *O Hepatitis E Streptococcal group B infection in an infant younger than 90 days of age, (American trypanosomiasis) invasive disease Chancroid HIV infection and related disease Streptococcus pneumoniae infection (pneumococcal invasive disease) Chikungunya Influenza-associated mortality in a child 1 Syphilis Chlamydia trachomatis infection Legionellosis (Legionnaires’ disease) *O Taeniasis * Cholera Leptospirosis Tetanus Coccidioidomycosis (Valley Fever) Listeriosis Toxic shock syndrome Colorado tick fever Lyme disease Trichinosis O Conjunctivitis, acute Lymphocytic choriomeningitis Tuberculosis, active disease Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease Malaria Tuberculosis latent infection in a child 5 years of age or younger (positive screening test result) *O Cryptosporidiosis -

1245 Zoonoses and Meliodosis

Zoonoses and Meliodosis Grant Waterer MBBS PhD MBA FRACP FCCP MRCP Professor of Medicine, University of Western Australia Professor of Medicine, Northwestern University, Chicago Conflicts of interest • I have no conflicts of interest related to this presentation • I am humbled and concerned to have to talk about meliodosis in Thailand! Pulmonary Zoonoses • Viruses – Hanta virus, MERS, Avian Influenza • Bacterial – Q Fever, Chlamydia spp (inc Psittacosis)., Mycoplasm spp., – Brucella, Leptospira, Tularemia, Yersinia, Streptococcus zooepidemicus • Protozoa – More of a problem in solid organs (Trypanasoma cruzi, Toxoplasma gondii etc) Question 1 • Spending 24 hours in an enclosed space with which of the following would not put you at risk of a zoonoses causing pneumonia? • A – a chicken • B – a pig • C – a chimpanzee • D – a camel • E – a bat • F – all of the above Question 1 • Spending 24 hours in an enclosed space with which of the following would not put you at risk of a zoonoses causing pneumonia? • A – a chicken • B – a pig • C – a chimpanzee • D – a camel • E – a bat • F – all of the above COMMONLY PERCEIVED BIOTERROSISM THREATS • CDC category A – Easily transmitted or high person to person – Likely high mortality – High social impact/potential for panic – Anthrax, plague, smallpox, tularemia – Botulism, Ebola, Marburg, Lassa, other South American haemorrhagic fevers COMMONLY PERCEIVED BIOTERRORISM THREATS • CDC category B – Brucellosis – Ricin – Glanders (Burkholderia mallei) – Melioidosis (Burkholderia pseudomallei) – Psittacosis -

Health Alert Network Advisory: Tick-Borne Diseases in Nebraska

TO: Primary care providers, infectious disease, laboratories, infection control, and public health FROM Thomas J. Safranek, M.D. Jeff Hamik, MS State Epidemiologist Vector-borne Disease Epidemiologist 402-471-2937 PHONE 402-471-1374 PHONE 402-471-3601 FAX 402-471-3601 FAX RE: TICK-BORNE DISEASES IN NEBRASKA DATE: May 6, 2020 The arrival of spring marks the beginning of another tick season. In the interest of public health and prevention, our office seeks to inform Nebraska health care providers about the known tick- borne diseases in our state. Spotted fever rickettsia (SFR) including Rocky Mountain spotted fever (RMSF) SFR is a group of related bacteria that can cause spotted fevers including RMSF. Several of these SFR have similar signs and symptoms, including fever, headache, and rash, but are often less severe than RMSF. SFR are the most commonly reported tick-borne disease in Nebraska. Our office has reported a median of 26 cases (range 16-48) with SFR over the last 5 years (2015- 2019), an increase from 10 median cases (range 5-18) reported during 2010-2014. SFR, especially RMSF NEEDS TO BE A DIAGNOSTIC CONSIDERATION IN ANY PERSON WITH A FEVER AND A HISTORY OF EXPOSURE TO ENVIRONMENTS WHERE TICKS MIGHT BE PRESENT. The skin rash is not always present when the patient first presents to a physician. RMSF is frequently overlooked or misdiagnosed, with numerous reports of serious and sometimes fatal consequences. Nebraska experienced a fatal case of confirmed RMSF in 2015 where the diagnosis was missed and treatment was delayed until the disease was well advanced. -

Tick-Borne Diseases Dutchess County, New York Geographic Distribution of Tick-Borne Disease in the United States

Tick-Borne Diseases Dutchess County, New York Geographic distribution of tick-borne disease in the United States Overview Tick-borne disease in Dutchess County, NY Recently recognized tick-borne diseases Infectious Tick-borne Diseases in the United States Endemic to Dutchess County, NY Endemic in other parts of the USA • Lyme disease (borreliosis) • Colorado tick fever • Anaplasmosis • Southern tick-associated rash • Babesiosis illness (STARI) • Ehrlichiosis • Tickborne relapsing fever • Powassan disease • Rickettsia parkeri rickettsiosis • Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever • 364D rickettsiosis • Tularemia • Heartland virus • Borrelia miyamotoi * • Borrelia mayonii Reference: http://www.cdc.gov/ticks/diseases/index.html Tick Paralysis Non-infectious Tick-Borne Syndrome Tick Paralysis The illness is caused by a neurotoxin produced in the tick's salivary gland. After prolonged attachment, the engorged tick transmits the toxin to its host Tick Paralysis Symptoms 2- 7 days after attachment Acute, ascending flaccid paralysis that is confused with other neurologic disorders The condition can worsen to respiratory failure and death in about (10%) of the cases Pathogenesis of Tick Paralysis Tick paralysis is chemically induced by the tick and therefore usually only continues in its presence. Once the tick is removed, symptoms usually diminish rapidly. However, in some cases, profound paralysis can develop and even become fatal before anyone becomes aware of a tick's presence Only 2 Human Cases Reported in Dutchess County Since 1995 Ticks that cause tick paralysis are found in almost every region of the world. In the United States, most reported cases have occurred in the Rocky Mountain states, the Pacific Northwest and parts of the South. -

The Biblical Plague of the Philistines Now Has a Name, Tularemia

Medical Hypotheses (2007) 69, 1144–1146 http://intl.elsevierhealth.com/journals/mehy The biblical plague of the Philistines now has a name, tularemia Siro Igino Trevisanato * 2449 Felhaber Crescent, Oakville, Ontario, Canada L6H 7N8 Received 16 February 2007; accepted 20 February 2007 Summary An epidemic thought to have been the first instance of bubonic plague in the Mediterranean reveals to have been an episode of tularemia. The deadly epidemic took place in the aftermath of the removal of a wooden box from an isolated Hebrew sanctuary. Death, tumors, and rodents thereafter plagued Philistine country. Unlike earlier explanations proposed, tularemia caused by Francisella tularensis exhaustively explains the outbreak. Tularemia fits all the requirements indicated in the biblical text: it is carried by animals, is transmitted to humans, results in the development of ulceroglandular formations, often misdiagnosed for bubonic plague, and is fatal. Moreover, there is the evidence from the box and rodents: mice, which are known carrier for F. tularensis and can communicate it to humans, were credited by the very Philistines to be linked to the outbreak, and are small enough to nest in the box. Mice also explain the otherwise odd statement in the biblical text of a small Philistine idol repeatedly falling on the floor at night in the building where the Philistines had stored the box as mice exiting the box would easily have tipped over the statuette. Tularemia scores yet another point: an episode of the disease is known to have originated in Canaan and spread to Egypt around 1715 BC, indicating recurrence for the disease, and suggesting Canaan was a reservoir for F.