From Letea Forest (The Danube Delta Biosphere Reservation, Romania)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bird Numbers 2019

Bird Numbers 2019 Counting birds counts Book of Abstracts © Joaquim Antunes st 21 Conference of the European Bird Census Council ISBN: 978-989-8550-85-9 This page was intentionally left in blank Imprint Editors João E. Rabaça, Carlos Godinho, Inês Roque LabOr-Laboratory of Ornithology, ICAAM, University of Évora Scientific Committee Aleksi Lehikoinen (chair), Ruud Foppen, Lluís Brotons, Mark Eaton, Henning Heldbjerg, João E. Rabaça, Carlos Godinho, Rui Lourenço, Oskars Keišs, Verena Keller Organising Committee João E. Rabaça, Carlos Godinho, Inês Roque, Rui Lourenço, Pedro Pereira, Ruud Foppen, Aleksi Lehikoinen Volunteer team André Oliveira, Cláudia Lopes, Inês Guise, Patrícia Santos, Pedro Freitas, Pedro Ribeiro, Rui Silva, Sara Ornelas, Shirley van der Horst Recommended citation Rabaça, J.E., Roque, I., Lourenço, R. & Godinho, C. (Eds.) 2019: Bird Numbers 2019: counting birds counts. Book of Abstracts of the 21st Conference of the European Bird Census Council. University of Évora, Évora. ISBN: 978-989-8550-85-9 Bird Numbers 2019: counting birds counts The logo of the Conference pictures two species with different stories: the Woodchat Shrike Lanius senator and the Dartford Warbler Sylvia undata, both occurring in Alentejo. The first is a LC species currently suffering a moderate decline in Spain and Portugal; the second is a resident bird classified as NT which is declining in Europe at a moderate rate and seemingly increasing in Portugal, a country that holds 25% of its European population. Bird Numbers 2019 Counting birds counts -

Arachnida: Araneae) from Dobruja (Romania and Bulgaria) Liviu Aurel Moscaliuc

Travaux du Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle © 31 août «Grigore Antipa» Vol. LV (1) pp. 9–15 2012 DOI: 10.2478/v10191-012-0001-2 NEW FAUNISTIC RECORDS OF SPIDERS (ARACHNIDA: ARANEAE) FROM DOBRUJA (ROMANIA AND BULGARIA) LIVIU AUREL MOSCALIUC Abstract. A number of spider species were collected in 2011 and 2012 in various microhabitats in and around the village Letea (the Danube Delta, Romania) and on the Bulgarian Dobruja Black Sea coast. The results are the start of a proposed longer survey of the spider fauna in the area. The genus Spermophora Hentz, 1841 (with the species senoculata), Xysticus laetus Thorell, 1875 and Trochosa hispanica Simon, 1870 are mentioned in the Romanian fauna for the first time. Floronia bucculenta (Clerck, 1757) is at the first record for the Bulgarian fauna. Diagnostic drawings and photographs are presented. Résumé. En 2011 et 2012, on recueille des espèces d’araignées dans des microhabitats différents autour du village de Letea (le delta du Danube) et le long de la côte de la Mer Noire dans la Dobroudja bulgare. Les résultats sont le début d’une enquête proposée de la faune d’araignée dans la région. Le genre Spermophora Hentz, 1841 (avec l’espèce senoculata), Xysticus laetus Thorell, 1875 et Trochosa hispanica Simon, 1870 sont mentionnés pour la première fois dans la faune de Roumanie. Floronia bucculenta (Clerck, 1757) est au premier enregistrement pour la faune bulgare. Aussi on présente les dessins de diagnose et des photographies. Key words: Spermophora senoculata, Xysticus laetus, Trochosa hispanica, Floronia bucculenta, first record, spiders, fauna, Romania, Bulgaria. INTRODUCTION The results of this paper come from the author’s regular field work. -

The Importance of Protected Natural Areas

http://proceedings.lumenpublishing.com/ojs/index.php/lumenproceedings International Conference « Global interferences of knowledge society », November 16-17th, 2018, Targoviste, Romania Global Interferences of Knowledge Society The Importance of Protected Natural Areas Constantin POPESCU, Maria-Luiza HRESTIC https://doi.org/10.18662/lumproc.137 How to cite: Popescu, C., & Hrestic, M.-L. (2019). The Importance of Protected Natural Areas. In M. Negreponti Delivanis (ed.), International Conference «Global interferences of knowledge society», November 16-17th, 2018, Targoviste, Romania (pp. 201-212). Iasi, Romania: LUMEN Proceedings. https://doi.org/10.18662/lumproc.137 © The Authors, LUMEN Conference Center & LUMEN Proceedings. Selection and peer-review under responsibility of the Organizing Committee of the conference International Conference « Global interferences of knowledge society », November 16-17th, 2018, Targoviste, Romania The Importance of Protected Natural Areas Constantin POPESCU1, Maria-Luiza HRESTIC2* Abstract Economic relationships lead to the determination of behavior towards resources, including those related to biodiversity. Economic relationships lead to the determination of behavior towards resources, including those related to biodiversity. Human interventions are not negative only by making maximum use of biological resources, but also through activities that do not directly target these categories. The main ways humans contribute to the degradation of biodiversity are: modification and destruction of habitats, voluntary and involuntary transfer of species, overexploitation in all areas, starting with resources. The purpose of this research is to highlight the importance of protected areas in the world, as well as in Romania, highlighting economic activities that help to preserve and protect nature and the natural environment, activities that are included in management plans for sustainable development. -

Romania: Danube Delta Integrated Sustainable Development Strategy

Romania: Danube Delta Integrated Sustainable Development Strategy About the Danube Delta Region The Danube Delta is one of the continent’s most valuable habitats for specific delta wildlife and biodiversity. Established as a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve and a Ramsar site in 1990, it is the Europe’s second largest delta, and the best preserved of European deltas. The most significant physical and ecological feature of the Danube Delta is its vast expanse of wetlands, including freshwater marsh, lakes and ponds, streams and channels. With an area of 3,446 km2, is the world’s largest wetland. Only 9% of the area is permanently above water. The Delta hosts extraordinary biodiversity and provides important environmental services. It is the home of over 1,200 varieties of plants, 300 species of birds, as well as 45 freshwater fish species in its numerous lakes and marshes. There are 16 strictly protected areas in the delta where no economic activities are allowed, and areas for ecological rehabilitation and buffer zones between economical areas where tourist activities are permitted as long as the environment is protected. Dual Challenge in Developing the Danube Delta A dual challenge for the sustainable development of the Danube Delta is the conservation of its ecological assets and improvement of the quality of life for its residents. The Danube Delta is the largest remaining natural delta in Europe and one of the largest in the world. It is also the only river that is entirely contained within a Biosphere Reserve. It is important to conserve all of its ecological assets. 1 Danube Delta is perhaps one of the least inhabited regions of temperate Europe, with only about 10,000 people in one town (Sulina) and about 20 scattered villages. -

Populus Alba White Poplar1 Edward F

Fact Sheet ST-499 October 1994 Populus alba White Poplar1 Edward F. Gilman and Dennis G. Watson2 INTRODUCTION White Poplar is a fast-growing, deciduous tree which reaches 60 to 100 feet in height with a 40 to 50-foot-spread and makes a nice shade tree, although it is considered short-lived (Fig. 1). The dark green, lobed leaves have a fuzzy, white underside which gives the tree a sparkling effect when breezes stir the leaves. These leaves are totally covered with this white fuzz when they are young and first open. The fall color is pale yellow. The flowers appear before the leaves in spring but are not showy, and are followed by tiny, fuzzy seedpods which contain numerous seeds. It is the white trunk and bark of white poplar which is particularly striking, along with the beautiful two-toned leaves. The bark stays smooth and white until very old when it can become ridged and furrowed. The wood of White Poplar is fairly brittle and subject to breakage in storms and the soft bark is subject to injury from vandals. Leaves often drop from the tree beginning in summer and continue dropping through the fall. Figure 1. Middle-aged White Poplar. GENERAL INFORMATION Scientific name: Populus alba DESCRIPTION Pronunciation: POP-yoo-lus AL-buh Common name(s): White Poplar Height: 60 to 100 feet Family: Salicaceae Spread: 40 to 60 feet USDA hardiness zones: 4 through 9 (Fig. 2) Crown uniformity: irregular outline or silhouette Origin: not native to North America Crown shape: oval Uses: reclamation plant; shade tree; no proven urban toleranceCrown density: open Availability: somewhat available, may have to go out Growth rate: fast of the region to find the tree Texture: coarse 1. -

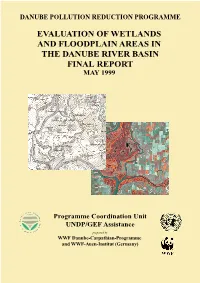

Evaluation of Wetlands and Floodplain Areas in the Danube River Basin Final Report May 1999

DANUBE POLLUTION REDUCTION PROGRAMME EVALUATION OF WETLANDS AND FLOODPLAIN AREAS IN THE DANUBE RIVER BASIN FINAL REPORT MAY 1999 Programme Coordination Unit UNDP/GEF Assistance prepared by WWF Danube-Carpathian-Programme and WWF-Auen-Institut (Germany) DANUBE POLLUTION REDUCTION PROGRAMME EVALUATION OF WETLANDS AND FLOODPLAIN AREAS IN THE DANUBE RIVER BASIN FINAL REPORT MAY 1999 Programme Coordination Unit UNDP/GEF Assistance prepared by WWF Danube-Carpathian-Programme and WWF-Auen-Institut (Germany) Preface The "Evaluation of Wetlands and Flkoodplain Areas in the Danube River Basin" study was prepared in the frame of the Danube Pollution Reduction Programme (PRP). The Study has been undertaken to define priority wetland and floodplain rehabilitation sites as a component of the Pollution reduction Programme. The present report addresses the identification of former floodplains and wetlands in the Danube River Basin, as well as the description of the current status and evaluation of the ecological importance of the potential for rehabilitation. Based on this evaluation, 17 wetland/floodplain sites have been identified for rehabilitation considering their ecological importance, their nutrient removal capacity and their role in flood protection. Most of the identified wetlands will require transboundary cooperation and represent an important first step in retoring the ecological balance in the Danube River Basin. The results are presented in the form of thematic maps that can be found in Annex I of the study. The study was prepared by the WWF-Danube-Carpathian-Programme and the WWF-Auen-Institut (Institute for Floodplains Ecology, WWF-Germany), under the guidance of the UNDP/GEF team of experts of the Danube Programme Coordination Unit (DPCU) in Vienna, Austria. -

Book of Abstracts

Annual Zoological Congress of “Grigore Antipa” Museum 23-25 November 2011 Bucharest - Romania Book of Abstracts Edited by: Dumitru Murariu, Costică Adam, Gabriel Chişamera, Elena Iorgu, Luis Ovidiu Popa, Oana Paula Popa Annual Zoological Congress of “Grigore Antipa” Museum 23-25 NOVEMBER 2011 BUCHAREST, ROMANIA Book of Abstracts Edited by: Dumitru Murariu, Costică Adam, Gabriel Chişamera, Elena Iorgu, Luis Ovidiu Popa, Oana Paula Popa DEDICATION CZGA 2011 is dedicated to the memory of Academician Nicolae BOTNARIUC, Senior researcher Teodor T. NALBANT, Professor Dr. Constantin PISICĂ, Dr. Alexandrina NEGREA CZGA 2011 Organizing Committee Chair: Dumitru MURARIU (“Grigore Antipa” National Museum of Natural History) Members: Costică ADAM (“Grigore Antipa” National Museum of Natural History) Gabriel CHIŞAMERA (“Grigore Antipa” National Museum of Natural History) Marieta COSTACHE (Faculty of Biology, University of Bucharest, Romania) Elena Iulia IORGU (“Grigore Antipa” National Museum of Natural History) Ionuţ Ştefan IORGU (“Grigore Antipa” National Museum of Natural History) Luis Ovidiu POPA (“Grigore Antipa” National Museum of Natural History) Oana Paula POPA (“Grigore Antipa” National Museum of Natural History) Melanya STAN (“Grigore Antipa” National Museum of Natural History) CZGA 2011 Scientific Committee Chair: Acad. Dr. Maya SIMIONESCU President of the Section of Biological Sciences - Romanian Academy; Director of the Institute for Cellular Biology and Pathology “Nicolae Simionescu”, The Romanian Academy, Bucharest, Romania Members: Conf. univ. Dr. Luminiţa BEJENARU Faculty of Biology, “Alexandru Ioan Cuza” University of Iaşi, Romania Dr. Imad CHERKAOUI Biology Department, Faculty of Sciences, “Mohammed V” University - Agdal, Rabat, Morocco; Head of the BirdLife Morocco Country Programme; SEO/BirdLife International representative and WetCap project Regional Coordinator Prof. -

Poplar Chap 1.Indd

Populus: A Premier Pioneer System for Plant Genomics 1 1 Populus: A Premier Pioneer System for Plant Genomics Stephen P. DiFazio,1,a,* Gancho T. Slavov 1,b and Chandrashekhar P. Joshi 2 ABSTRACT The genus Populus has emerged as one of the premier systems for studying multiple aspects of tree biology, combining diverse ecological characteristics, a suite of hybridization complexes in natural systems, an extensive toolbox of genetic and genomic tools, and biological characteristics that facilitate experimental manipulation. Here we review some of the salient biological characteristics that have made this genus such a popular object of study. We begin with the taxonomic status of Populus, which is now a subject of ongoing debate, though it is becoming increasingly clear that molecular phylogenies are accumulating. We also cover some of the life history traits that characterize the genus, including the pioneer habit, long-distance pollen and seed dispersal, and extensive vegetative propagation. In keeping with the focus of this book, we highlight the genetic diversity of the genus, including patterns of differentiation among populations, inbreeding, nucleotide diversity, and linkage disequilibrium for species from the major commercially- important sections of the genus. We conclude with an overview of the extent and rapid spread of global Populus culture, which is a testimony to the growing economic importance of this fascinating genus. Keywords: Populus, SNP, population structure, linkage disequilibrium, taxonomy, hybridization 1Department of Biology, West Virginia University, Morgantown, West Virginia 26506-6057, USA; ae-mail: [email protected] be-mail: [email protected] 2 School of Forest Resources and Environmental Science, Michigan Technological University, 1400 Townsend Drive, Houghton, MI 49931, USA; e-mail: [email protected] *Corresponding author 2 Genetics, Genomics and Breeding of Poplar 1.1 Introduction The genus Populus is full of contrasts and surprises, which combine to make it one of the most interesting and widely-studied model organisms. -

The Zooplankton of the Danube-Black Sea Canal in the First Two Decades of the Ecosystem Existence Victor Zinevici, Laura Parpală, Larisa Florescu, Mirela Moldoveanu

Travaux du Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle © 30 décembre «Grigore Antipa» Vol. LVI (2) pp. 227–251 2013 DOI: 10.2478/travmu-2013-0017 THE ZOOPLANKTON OF THE DANUBE-BLACK SEA CANAL IN THE FIRST TWO DECADES OF THE ECOSYSTEM EXISTENCE VICTOR ZINEVICI, LAURA PARPALĂ, LARISA FLORESCU, MIRELA MOLDOVEANU Abstract. This paper reports the invasive subspecies Podonevadne trigona ovum (Zernov, 1901), as dominant in the Danube-Black Sea Canal. In the first two years of the existence of the anthropogenic ecosystem (1985-1986) the zooplankton summarizes only 72 species. Over two decades it recorded the presence of 127 species. As a result of nutrient accumulation, in 2005, the zooplankton abundance has significantly increased, reaching 330 ind L-1, followed by an evident growth of biomass (2285 μg wet weight L-1). In 2005, the productivity registered 731.8 μg wet weight L-1/24h. Résumé. Le présent papier rapport l’existence de la sous-espèce envahissante Podonevadne trigona ovum (Zernov, 1901), dominante dans le canal Danube – Mer Noire. La sous-espèce appartient à l’ordre Onychopoda, et elle a une origine Caspienne. Dans les premières deux années qui suit l’apparition de cet écosystème anthropogénique (1985-1986), le zooplancton a été reprèsenté par 72 espèces; après deux décennies, le nombre d’espèces a augmenté à 127. A la suite d’accumulation de nutriments, en 2005 l’abondance du zooplancton a augmentée de manière significative, atteignant 330 ind L-1, suivie d’une augmentation marquée de la biomasse (2285 mg s.um. L-1). En 2005, la productivité du zooplancton a enregistré 731,8 mg mat.hum. -

MEMORIAE INGENII Octombrie 2013

MEMORIAE INGENII Octombrie 2013 www.mnt-leonida.ro EVENIMENT EXPOZIȚIONAL OMAGIAL FONDATORI DE MUZEE 3-27 130ANI octombrie 2013 Mi-Du (Luni si Marti inchis) 10-18h Str. Candiano Popescu 2 Sector 4, Bucuresti PARCUL CAROL ISSN 1841-1568 MEMORIAE INGENII ISSN 1841-1568 www.mnt-leonida.ro Octombrie 2013 SUMAR Exerciţiu de memorie / Cristina UNTEA 1 Muzee şi fondatori / Laura Maria ALBANI, Director Muzeul Național Tehnic 2 “Prof. Ing. Dimitrie Leonida” Viaţa şi opera baronului Samuel von Brukenthal / Prof. univ. dr. Sabin Adrian LUCA, 5 Director General Muzeul Național Brukenthal - Sibiu Grigore Antipa - Fondatorul instituţiei care îi poartă numele şi inventatorul expoziţiilor 13 muzeale, dioramatice / Dumitru MURARIU, Director General al Muzeului Național de Istorie Naturală “Grigore Antipa“ Alexandru Tzigara-Samurcaş: un părinte fondator / Dr. Virgil Ștefan NIȚULESCU, 18 Director General Muzeul Național al Țăranului Român Dimitrie Gusti (1880-1955) / Conf. Univ. dr. Paula POPOIU, Director General 20 Muzeul Național al Satului “Dimitrie Gusti” Momente şi personalităţi ce au marcat înfiinţarea şi evoluţia Muzeului Ştiinţei şi Tehnicii 24 „Ştefan Procopiu” din Iaşi / Ing. Teodora-Camelia CRISTOFOR, muzeograf Muzeul Științei și Tehnicii „ŞTEFAN PROCOPIU” din IAŞI George Enescu – date biografice / dr. Adina SIBIANU, muzeograf 36 Muzeul Național “George Enescu” Observatorul Astronomic „Amiral Vasile Urseanu” și ctitorul său / Ref. Mihai Dascălu, 41 Muz. Șonka Adrian Muzeul Municipal Râmnicu Sărat – consideraţii asupra istoricului constituirii colecţiilor / 43 Marius NECULAE, Roxana VIŞAN Dimitrie Leonida - promotor al construirii unei reţele de canale navigabile interioare în 48 România / Aurel TUDORACHE, muzeograf Muzeul Național Tehnic “Prof. Ing. Dimitrie Leonida” Dimitrie Leonida – una din luminile Fălticenilor / Ovidiu MUSTAȚĂ 52 Povestea fotografiei (scurtă cronologie a tehnicii fotografice) / Ing. -

Taxons Dedicated to Grigore Antipa

Travaux du Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle “Grigore Antipa” 62 (1): 137–159 (2019) doi: 10.3897/travaux.62.e38595 RESEARCH ARTICLE Taxons dedicated to Grigore Antipa Ana-Maria Petrescu1, Melania Stan1, Iorgu Petrescu1 1 “Grigore Antipa” National Museum of Natural History, 1 Şos. Kiseleff, 011341 Bucharest 1, Romania Corresponding author: Ana-Maria Petrescu ([email protected]) Received 18 December 2018 | Accepted 4 March 2019 | Published 31 July 2019 Citation: Petrescu A-M, Stan M, Petrescu I (2019) Taxons dedicated to Grigore Antipa. Travaux du Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle “Grigore Antipa” 62(1): 137–159. https://doi.org/10.3897/travaux.62.e38595 Abstract A comprehensive list of the taxons dedicated to Grigore Antipa by collaborators, science personalities who appreciated his work was constituted from surveying the natural history or science museums or university collections from several countries (Romania, Germany, Australia, Israel and United States). The list consists of 33 taxons, with current nomenclature and position in a collection. Historical as- pects have been discussed, in order to provide a depth to the process of collection dissapearance dur- ing more than one century of Romanian zoological research. Natural calamities, wars and the evictions of the museum’s buildings that followed, and sometimes the neglection of the collections following the decease of their founder, are the major problems that contributed gradually to the transformation of the taxon/specimen into a historical landmark and not as an accessible object of further taxonomical inquiry. Keywords Grigore Antipa, museum, type collection, type specimens, new taxa, natural history, zoological col- lections. Introduction This paper is dedicated to 150 year anniversary of Grigore Antipa’s birth, the great Romanian scientist and the founding father of the modern Romanian zoology. -

Master Project ���������������������

Master project Table of Contents" " I.! Introduction!...............................................................................................................................!3! II.! History of Colonization and Ethnic Composition Today in the Region!...........................!4! Early settlements in the ancient world and the Middle Ages"...................................................."4! Rumanianization after WWI"..........................................................................................................."6! Communist Era"................................................................................................................................"6! Ethnic Diversity Today"..................................................................................................................."6! Traditions – Handicrafts – Religion".............................................................................................."7! Conclusion"......................................................................................................................................."8! Sources"............................................................................................................................................"8! Images".............................................................................................................................................."8! III.! Traditional Architecture and Urban Framework!..................................................................!9! Traditional Architecture".................................................................................................................."9!