1 the Sheep Value Chain and 'Wool Out' Sheepskin As a Sustainable

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sheep Breeding Technology

NATIONAL RESEARCH INSTITUTE OF ANIMAL PRODUCTION Sheep breeding technology Training materials of project IMPROFARM - Improvement of Production and Management Processes in Agriculture Through Transfer of Innovations, Leonardo da Vinci Transfer of Innovations programme, number 2011-1-PL1-LEO05-19878 www.improfarm.pl This project has been funded with support from the European Commission. This publication reflects the views only of the author and the Commission cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein. Content 1. Animal physiology ........................................................................................................................................................... 7 1.1 Naming of particular groups of sheep ..................................................................................................................................................................... 11 1.1 General bio-breeding characteristics of the sheep .................................................................................................................................................. 11 2. Types of utility ............................................................................................................................................................... 14 2.1 Woolly sheep ......................................................................................................................................................................................................... -

Scientific Support for the Innovative Development of Sheep Breeding in the Russian Federation

E3S Web of Conferences 254, 08013 (2021) https://doi.org/10.1051/e3sconf/202125408013 FARBA 2021 Scientific support for the innovative development of sheep breeding in the Russian Federation Тatiana Marinchenko* Federal State Budgetary Scientific Institution (Rosinformagrotekh FSBSI), Lesnaya Str., 60,Pravdinsky Township, 141261 Moscow Region, the Russian Federation Abstract. Increasing the output of agricultural products and improving their quality is one of the most important tasks of ensuring the food security of the Russian Federation. The main solution to this problem is the introduction of innovative technologies, which are the result of research and development. In this country, sheep breeding is developing in accordance with the tasks set by the government to increase output, improve quality and develop export potential. Currently, the main livestock of sheep is concentrated among farmers and households, which cannot provide breeding work and the introduction of innovations at the required level. The main consumers of innovations are agricultural organizations, which occupy a small share in terms of livestock and products. The aim of the study is to analyze the scientific potential of the industry from the standpoint of its sufficiency to solve the tasks set by the government. 1 Introduction Sheep breeding is out standing in the diversity and uniqueness of the products obtained (wool, lamb meat, milk, furs, sheepskin coats, etc.), in the ability to efficiently produce it through the use of natural and fodder resources in conditions of their limited availability and inaccessibility for other types of farm animals. As a result of the measures taken in the Russian Federation since 2000, the number of sheep increased 1.6 times and it amounted to 20.65 million heads in all categories of farms by the beginning of 2020. -

Skin Care &Protection

Skin Care & Protection by an Introduction TM to Shear Comfort BES Healthcare is a provider of specialised skin protection products for the requirements of modern healthcare. We have over two decades of experience in the all Shear Comfort™ Natural products retain the healthcare arena. Because of this experience • Lanolin, which proven efficacy of natural sheepskin (pressure we understand three key things about modern redistribution, shear reduction, water vapour healthcare: it can take time, it can cost money, causes some dissipation, and heat control), but can also go and it can be complicated. But this need not be people to be safely through standard thermal disinfection the case. We aim to address this with our range allergic to wool, procedures. Thus Shear Comfort™ Natural of products that not only improve the quality products can withstand multiple washes up to is removed from of life and assist in day-to-day living activities 80ºC, effectively killing any bacteria. A further TM of the end user. We also offer the clinician, Shear Comfort benefit of the tanning process is that it makes technician, or specialist an effective, affordable, in the tanning the skins urea-resistant, meaning that the and straightforward tool to achieve positive process leather will not harden as a result of interaction results time and time again. We do this through with skin secretions. the Shear Comfort™ range, of which our sister company, Healthcare Innovations Australia Pty • Wool can wick Shear Comfort XD1900™ Ltd (HIA), are the sole producer. away moisture, Along with the Shear Comfort™ range, we also manufacture an XD1900™ range of footwear re-distribute The Shear Comfort™ Natural range of skin and skin care products. -

First Supplement to General Order No. 179, Dated September 10, 1931

' e U.S. DEPARTMENT OF LABOR BUREAU OF IMMIGRATION WASHINGTON ADDRESS WLY TO COMMISSIONER GENERAL OF IMMIGRATION AND REFEllTO No. 55638 / 947-C November 7. 1932. A&P FIRST SUPPLEMENT TO GENERAL ORDER NO. 179 D.A.TED SEPTEMBER 10, 1931. SUBJECT: UNIFORMS - BORDER PATROL. In addition to, or as an alternative to. the overCO§t prescribed in General Order No. 179, a sheepskin lined overcoat con forming to the following specifications is hereby authorized as part of the uniform of immigration patrol of ficers: STYLE OF COAT Style: Double breasted; four leaf collar; three buttons on each side, top buttons to be under collar; length of coat to extend to nine (9) inches above knee. Color: Forestry green. Material: Cravenetted moleskin or similar material. Back Belt: To be one piece. two (2) inches wide, same material as coat; to be let inside seams without buttons. Pockets: Two outside pockets to be cut through at a 45 degree angle, top point to be even with hip bone and to be bound with leather; to be fitted with slit through lining to permit reaching side arms worn beneath overcoat; slit to be fitted with tabs on inside of coat to permit fastenining with buttons inside opening; one inside pocket on right side cut through lining and bound with leather; pocket linings to be of duck. Coat Lining: To be of properly prepared sheepskin, wool side exposed. Sleeve Lining: To be of sta.nd.ard lesterine. • 55638/947-C - 2 - Collar: To be of Kersey, 26 oz. in weight and forrestry green in color; four (4) inches at ends and five (5) inches at center; a flap three (3) inches wide made same as collar will be fitted to join ends of collar by buttons when turned up to protect neck and throat. -

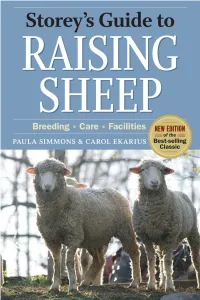

Storey's Guide to Raising Sheep

4TH EDITION Storey’s Guide to RAISING SHEEP Breeding · Care · Facilities PAULA SIMMONS & CAROL EKARIUS ß Storey Publishing The mission of Storey Publishing is to serve our customers by publishing practical information that encourages personal independence in harmony with the environment. Edited by Sarah Guare and Deborah Burns Art direction and book design by Cynthia McFarland Cover design by Kent Lew Text production by Jennifer Jepson Smith Front cover photograph by © Jason Houston Author photographs by Sunrise Printing, Inc. (Paula Simmons) and © Ken Woodard Photography (Carol Ekarius) Interior photography credits appear on page 438 Illustrations by © Elayne Sears, except for Brigita Fuhrmann 25, 279, 320; Chuck Galey 110, 113, 114, 122; Carol Jessop 2, Carl Kirkpatrick 117, 119; and © Storey Publishing, LLC 121, 159, 216, 220, 221 Indexed by Christine R. Lindemer, Boston Road Communications © 2009, 2001 by Storey Publishing, LLC All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages or reproduce illustrations in a review with appropriate credits; nor may any part of this book be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means — electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or other — without written permission from the publisher. The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. All recommendations are made without guarantee on the part of the author or Storey Publishing. The author and publisher disclaim any liability in connection with the use of this information. Storey books are available for special premium and promotional uses and for customized editions. -

THE CATHOLIC UNIVERSITY of AMERICA the Development And

THE CATHOLIC UNIVERSITY OF AMERICA The Development and Significance of the Religious Habit of Men A DISSERTATION Submitted to the Faculty of the School of Theology and Religious Studies Of The Catholic University of America In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree Doctor of Philosophy © Copyright All Rights Reserved By Peter F. Killeen Washington, D.C. 2015 The Development and Significance of the Religious Habit of Men Peter F. Killeen, Ph.D. Director: Raymond Studzinski, Ph.D. In light of the diminished status of the religious habit since Vatican II, this dissertation explores the development and significance of the religious habit of male institutes of the Western Church. Currently (2015), many older religious believe that consecrated life may be lived more faithfully without a religious habit, while a high percentage of younger religious desire to wear a habit as a visual expression of their consecration. This difference of opinion is a cause of tension within many religious institutes. Despite tremendous change in the use of the religious habit since Vatican II, the habit has received minimal scholarly attention, and practically none written in English. This dissertation engages the initial legislative texts of numerous religious institutes in an effort to present the historical development of the habit of male religious of the Western Church. It also gives magisterial directives on the habit that have been issued throughout the history of the Church. The dissertation summarizes theological themes that have traditionally been connected to the religious habit, and it engages theological interpretations that have emerged since Vatican II which have contributed to the diminishment of the religious habit. -

Chapter 1 Domesticated Sheep in Human History

> BACK TO CONTENTS PAGE CHAPTER 1 DOMESTICATED SHEEP IN HUMAN HISTORY The needs of our woolly companions are more complex than we realise. They have intelligence which is repeatedly underestimated. Don’t misjudge their ability to comprehend us. The apparent senseless behaviour of sheep comes from their natural position as a prey animal and their innate flighty behaviour is fear-based, it is not necessarily mindless. Sheep should be valued the same as any other animal however humans have significant practical reasons to raise sheep. For most of us, their uses outweigh the benefits of keeping these gentle animals simply as pets. Caption to go here Types of Sheep distinct breeds developed within this species that are diverse in size and Sheep are bovine animals (as are cattle, many other characteristics. There are antelope and goats) which belong to also various old species names given the genera ‘Ovis’. There are five living to sheep which are now redundant, species in this order as follows: including: Ovis musimon (from 1762) Ovis orientalis from 1774 and Ovis Ovis aries ophion from 1841. Some experts consider the domestic sheep’s wild This species name was given by ancestor to be a separate breed known Linnaeus in 1758 and is the preferred as Ovis orientalis, and identify two species name for what are commonly subspecies: Ovis orientalis orientalis known as Domestic Sheep, Red Sheep (the Moufloun Group) and Ovis or Mouflon. There are over 10,000 orientalis vignei (the Ural Group). page 7 > BACK TO CONTENTS PAGE Ovis canadensis Big Horn Sheep Colorado Ovis canedensis Ovis ammon Commonly known as Bighorn Sheep, Commonly known as Argali sheep, from the Rocky Mountains in North from central Asia, these are the largest America, rams of Ovis canedensis can species at up to 125 cm at the shoulder reach 125 kg. -

Module-4: Sheep

Learning about life on the farm and in the countryside Module 4 Curriculum links: Sheep • Science Living things Environmental awareness and care • Geography Human environments • SPHE Myself and the wider world Lesson objectives: To revise material covered in previous modules. To make students aware that there is more than one breed of sheep and to explain their digestive system. To create an awareness of the many different products that sheep provide us with. Teacher guidelines It is suggested that teachers ensure that students are familiar with the vocabulary and concepts introduced in the previous modules before starting this lesson. Keywords and concepts introduced in previous modules: ewe ram lamb bleat flock wool meat fleece shear shorn sheepdog hooves lambing spring grazing fodder Sheep provide us with wool, meat and milk for making cheese. A sheep’s fleece is shorn once per year in the spring. Farmers must trim the sheep’s hooves and dip them to prevent disease. Lambs are born in spring and they feed from their mothers’ milk for about 14 weeks. When there is not enough grass for the sheep to graze, the farmer gives them extra food called fodder. Keywords for this lesson: breed products mutton ruminants chewing the cud Fun fact Fun fact There are more than 800 Sheep are one of the oldest different breeds of sheep farming animals in the world and in the world have provided us with meat, milk, wool and leather for 11,000 years Sheep breeds There are many different breeds of sheep in Ireland and they fall into two categories, hill/mountain breeds and lowland breeds. -

Sheep Industry Report

The Great Sheep industry and its Juicy Fifth Quarter A MARKET SURVEY COMMISSIONED BY MEAT SOUTH WEST FOR THE SOUTH WEST of ENGLAND REGIONAL DEVELOPMENT AUTHORITY (SWRDA) 16/4/07M 16/4/07M The Great Sheep industry and its Juicy Fifth Quarter CONTENTS Section Page 1.1.1 Aims of the Study 1 1.1.2 Preface 1 1.1.3 Background 2 1.2 Market Overview 3 1.2.1F Fig.1 UK Sheep Industry Structure 3 1.2.2 The Sheep Industry, Key Facts and Figures 4 1.2.2F Fig.2 UK Sheepskin Industry Flowchart 5 1.2.3 The UK Fellmonger 6 1.2.3F Fig.3 Fellmongers in the UK, 1988 7 1.2.4 The UK Hide Market 8 1.2.4F Fig.4 Hide Markets in the UK 1988 10 1.2.4F Fig.5 UK Ovine Leather Flowchart 1988 11 1.2.5 The Meat Market - Abattoir and Butcher 11 1.2.6 Butchers 12 1.2.7 Supermarkets 13 1.2.8 FARMA 13 1.2.9 The UK Wool Industry 14 1.2.10 Sheep and Sheep Farmers 16 1.2.11F Fig.6 Sheep Farming Stratification Flowchart 17 1.2.11 The Sheep Industry Supply Chain - Conclusions 18 CONTENTS - Continued Section Page 1.3 The Sheepskin Industry 19 1.3.1 Origins in the South West of England, 1200 - 1900 19 1.3.2F Fig.7 UK Sheepskin Industry Structure Chart 20 1.3.2 20th Century Traditions 21 1.3.3 Sheepskin Product Offer 22 1.3.4 Sheepskin Exports 22 1.3.5 The UK Sheepskin Industry 1970 - 1989 23 1.3.6 The Merger and Monopoly Years 24 1.3.7 Sheepskin in the Vivienne Westwood Years 1980 - 2000 25 1.3.8 Global Sheepskin Overview 1990 - 2000 27 1.3.9 The Crash 28 1.3.10 The Sheepskin Industry, Planning for the 21st Century 29 1.3.11 The Sheep Industry, Planning for the 21st Century 31 -

PRE FW19 LOOKBOOK HERMIONE Coat

PRE FW19 LOOKBOOK HERMIONE Coat A tigrado shearling coat lines with textile. It is cut in an slightly oversized silhouette with two side pockets. A front button fastening. Available sizes: 34, 36, 38, 40 Sample size: 36 Available coulours: Chestnut Pearl Black The Pink 100% sheepskin textile lining Wholesale price 547€ CHINO Coat A toscana shearling coat lines with textile. It is cut in an slightly oversized silhouette with two side pockets. A front button fastening. Available sizes: 34, 36, 38, 40 Sample size: 36 Available coulours : Chestnut Pearl Black The Pink Glacier Grey 100% sheepskin textile lining Wholesale price 499€ LAURYN Coat A Toscana shearling coat with asymmetric ivory and black details. It is cut i slightly oversized silhouette with two side pockets. A front button fastening Available sizes: 34, 36, 38, 40 Sample size: 34 Available colours: Ivory/Black Almond/Ivory 100% sheepskin Wholesale price 611€ VERSAILLES Coat A long-lined toscana shearling coat with buckle- fastening cuffs. It has asymmetric patch details and has a slightly oversized silhouette with two side pockets. A front button fastening. Available sizes: 34, 36, 38, 40 Sample size: 36 Available colours : Almond/Ivory Black/Ivory Sheepskin Textile lining Wholesale price 662€ PUSHKI Coat A long-lined toscana shearling coat with buckle- fastening cuffs. It has a slightly oversized silhouette with two side pockets. A front button fastening. Available sizes: 34, 36, 38, 40 Sample size: 36 Available colours: Chestnut Pearl Black The Pink Glacier Grey Sheepskin Textile lining Wholesale price 635€ ALIYAH Coat A long-lined tigrado shearling coat. Detailed with a nappa leather belt and two sides pockets. -

Asi's Priority Policy Issues

ASI’S PRIORITY POLICY ISSUES ASI is the national organization representing the interests of the 100,000 sheep producers located throughout the United States. From East to West, farm flocks to range operations, ASI works to represent the interests of all producers. NATIONAL ANIMAL DISEASE PREPAREDNESS AND RESPONSE PROGRAM • Continued access to key technologies through the animal drugs for minor uses and minor species provision in the NADPRP is critical for the sheep industry. • ASI STRONGLY supports an annual allocation to USDA’s National Institute of Food and Agriculture for critical minor uses and minor species R&D through the former National Research Support Project No. 7 (NRSP-7). ELECTRONIC LOGGING MANDATE AND HOURS OF SERVICE • The Sheep Industry relies on the safe and efficient transportation of livestock every day of the year. • ASI supports reasonable statutory and regulatory exemptions to ensure both the safety of our nation’s highways and the welfare of the livestock being hauled. H2-A TEMPORARY AGRICULTURAL WORKERS • Sheep farmers and ranchers depend on a workable temporary foreign labor program to help care for more one-third of ewes and lambs in the U.S. and, for over 50 years, have used and helped craft the current provisions of the H2A program. • Any guest worker program MUST maintain special procedures for sheep producers and give our members a fighting chance to compete in an increasingly difficult financial environment, while protecting both domestic and foreign ag workers. • ASI secured sheep specific language in the Farm Workforce Modernization Act (H.R. 5038), but the “Limited Allocation for Certain Special Procedures Industries” must not be less than 2,500 and codify special procedures in final legislation. -

TRADITIONAL SHEEP KEEPING on Estonian and Finnish Coast and Islands TRADITIONAL SHEEP KEEPING KEEPING SHEEP TRADITIONAL

TRADITIONAL SHEEP KEEPING On Estonian and Finnish coast and islands TRADITIONAL SHEEP KEEPING A publication of the Knowsheep-project Tallinn 2013 TRADITIONAL SHEEP KEEPING On Estonian and Finnish coast and islands Studies carried out by Interreg IVA KNOWSHEEP Tallinn 2013 S K Ä R GÅRDSSTADE N SAARISTOKAUPUNK I The Knowsheep-project is financed by European Union, European Regional Development Fund, Central Baltic Interreg IV A Programme 2007-2013, Archipelago and Islands Sub-programme. This publication reflects the authors’ views and the Managing Authority can- - not be held liable for the information published by the project partners. Authors carry all the responsibility for the use of illustrative materials in their articles. Editor: Veiko Kastanje Technical editor: Svea Aavik Translator: Luisa Translation Bureau Printed in Estonia by Rebellis Front cover photo: Annika Michelson Back cover photo: Veiko Kastanje © Estonian Crop Research Institute ISBN 978-9949-9504-5-4 Contents Introduction 4 1. T. Järvis Sheep parasites and their control 7 2. T. Järvis, E. Mägi Parasitological situation of sheep farms on the Baltic Sea islands 30 3. K. Kabun Wool: structure and properties 52 4. A. Michelson Experiences of free-ranging Estonian native sheep. Case: Kiltsi Meadow 60 5. T. Otstavel Large carnivore and eagle damage prevention measures in Estonian and Finnish Baltic islands and coastal areas 95 6. R. Räikkönen, S. Kurppa Knowsheep-project on the resources and development needs of the sheep industry in Finnish and Estonian coastal and island regions 139 7. U. Tamm, L. Kütt Sheep feeds and feeding characteristics in the Baltic Sea region 188 3 Introduction This collection contains articles on the results of research and devel- opment activities carried out from 2011–2013 within the scope of the KNOWSHEEP project.