1 Social Choice Or Collective Decision-Making: What Is Politics All About?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introduction to Computational Social Choice

1 Introduction to Computational Social Choice Felix Brandta, Vincent Conitzerb, Ulle Endrissc, J´er^omeLangd, and Ariel D. Procacciae 1.1 Computational Social Choice at a Glance Social choice theory is the field of scientific inquiry that studies the aggregation of individual preferences towards a collective choice. For example, social choice theorists|who hail from a range of different disciplines, including mathematics, economics, and political science|are interested in the design and theoretical evalu- ation of voting rules. Questions of social choice have stimulated intellectual thought for centuries. Over time the topic has fascinated many a great mind, from the Mar- quis de Condorcet and Pierre-Simon de Laplace, through Charles Dodgson (better known as Lewis Carroll, the author of Alice in Wonderland), to Nobel Laureates such as Kenneth Arrow, Amartya Sen, and Lloyd Shapley. Computational social choice (COMSOC), by comparison, is a very young field that formed only in the early 2000s. There were, however, a few precursors. For instance, David Gale and Lloyd Shapley's algorithm for finding stable matchings between two groups of people with preferences over each other, dating back to 1962, truly had a computational flavor. And in the late 1980s, a series of papers by John Bartholdi, Craig Tovey, and Michael Trick showed that, on the one hand, computational complexity, as studied in theoretical computer science, can serve as a barrier against strategic manipulation in elections, but on the other hand, it can also prevent the efficient use of some voting rules altogether. Around the same time, a research group around Bernard Monjardet and Olivier Hudry also started to study the computational complexity of preference aggregation procedures. -

Social Choice Theory Christian List

1 Social Choice Theory Christian List Social choice theory is the study of collective decision procedures. It is not a single theory, but a cluster of models and results concerning the aggregation of individual inputs (e.g., votes, preferences, judgments, welfare) into collective outputs (e.g., collective decisions, preferences, judgments, welfare). Central questions are: How can a group of individuals choose a winning outcome (e.g., policy, electoral candidate) from a given set of options? What are the properties of different voting systems? When is a voting system democratic? How can a collective (e.g., electorate, legislature, collegial court, expert panel, or committee) arrive at coherent collective preferences or judgments on some issues, on the basis of its members’ individual preferences or judgments? How can we rank different social alternatives in an order of social welfare? Social choice theorists study these questions not just by looking at examples, but by developing general models and proving theorems. Pioneered in the 18th century by Nicolas de Condorcet and Jean-Charles de Borda and in the 19th century by Charles Dodgson (also known as Lewis Carroll), social choice theory took off in the 20th century with the works of Kenneth Arrow, Amartya Sen, and Duncan Black. Its influence extends across economics, political science, philosophy, mathematics, and recently computer science and biology. Apart from contributing to our understanding of collective decision procedures, social choice theory has applications in the areas of institutional design, welfare economics, and social epistemology. 1. History of social choice theory 1.1 Condorcet The two scholars most often associated with the development of social choice theory are the Frenchman Nicolas de Condorcet (1743-1794) and the American Kenneth Arrow (born 1921). -

Social Choice (6.154.11)

SOCIAL CHOICE (6.154.11) Norman Scho…eld Center in Political Economy Washington University in Saint Louis, MO 63130 USA Phone: 314 935 4774 Fax: 314 935 4156 E-mail: scho…[email protected] Key words: Impossibility Theorem, Cycles, Nakamura Theorem, Voting.. Contents 1 Introduction 1.1 Rational Choice 1.2 The Theory of Social Choice 1.3 Restrictions on the Set of Alternatives 1.4 Structural Stability of the Core 2 Social Choice 2.1 Preference Relations 2.2 Social Preference Functions 2.3 Arrowian Impossibility Theorems 2.4 Power and Rationality 2.5 Choice Functions 3 Voting Rules 3.1 Simple Binary Preferences Functions 3.2 Acyclic Voting Rules on Restricted Sets of Alternatives 4 Conclusion Acknowledgement Glossary Bibliography 1 Summary Arrows Impossibility implies that any social choice procedure that is rational and satis…es the Pareto condition will exhibit a dictator, an individual able to control social decisions. If instead all that we require is the procedure gives rise to an equilibrium, core outcome, then this can be guaranteed by requiring a collegium, a group of individuals who together exercise a veto. On the other hand, any voting rule without a collegium is classi…ed by a number,v; called the Nakumura number. If the number of alternatives does not exceed v; then an equilibrium can always be guaranteed. In the case that the alternatives comprise a subset of Euclden spce, of dimension w; then an equilibrium can be guaranteed as long as w v 2: In general, however, majority rule has Nakumura number of 3, so an equilibrium can only be guaranteed in one dimension. -

Neoliberal Reason and Its Forms: Depoliticization Through Economization∗

Neoliberal reason and its forms: Depoliticization through economization∗ Yahya M. Madra Department of Economics Boğaziçi University Bebek, 34342, Istanbul, Turkey [email protected] Yahya M. Madra studied economics in Istanbul and Amherst, Massachusetts. He has taught at the universities of Massachusetts and Boğaziçi, and at Skidmore and Gettysburg Colleges. He currently conducts research in history of modern economics at Boğaziçi University with the support of TÜBITAK-BIDEB Scholarship. His work appeared in Journal of Economic Issues, Rethinking Marxism, The European Journal of History of Economic Thought, Psychoanalysis, Society, Culture and Subjectivity as well as edited volumes. His current research is on the role of subjectivity in political economy of capitalism and post-capitalism. and Fikret Adaman Department of Economics, Boğaziçi University Bebek, 34342, Istanbul, Turkey [email protected] Fikret Adaman studied economics in Istanbul and Manchester. He has been lecturing at Boğaziçi University on political economy, ecological economics and history of economics. His work appeared in Journal of Economic Issues, New Left Review, Cambridge Journal of Economics, Economy and Society, Ecological Economics, The European Journal of History of Economic Thought, Energy Policy and Review of Political Economy as well as edited volumes. His current research is on the political ecology of Turkey. DRAFT: Istanbul, October 3, 2012 ∗ Earlier versions of this paper have been presented in departmental and faculty seminars at Gettysburg College, Uludağ University, Boğaziçi University, İstanbul University, University of Athens, and New School University. The authors would like to thank the participants of those seminars as well as to Jack Amariglio, Michel Callon, Pat Devine, Harald Hagemann, Stavros Ioannides, Ayşe Mumcu, Ceren Özselçuk, Maliha Safri, Euclid Tsakalatos, Yannis Varoufakis, Charles Weise, and Ünal Zenginobuz for their thoughtful comments and suggestions on the various versions of this paper. -

1 Democratic Deliberation and Social Choice: a Review Christian List1

1 Democratic Deliberation and Social Choice: A Review Christian List1 This version: June 2017 Forthcoming in the Oxford Handbook of Deliberative Democracy 1. Introduction In normative political theory, it is widely accepted that democratic decision making cannot be reduced to voting alone, but that it requires reasoned and well-informed discussion by those involved in and/or subject to the decisions in question, under conditions of equality and respect. In short, democracy requires deliberation (e.g., Cohen 1989; Gutmann and Thompson 1996; Dryzek 2000; Fishkin 2009; Mansbridge et al. 2010). In formal political theory, by contrast, the study of democracy has focused less on deliberation, and more on the aggregation of individual preferences or opinions into collective decisions – social choices – typically through voting (e.g., Arrow 1951/1963; Riker 1982; Austen-Smith and Banks 2000, 2005; Mueller 2003). While the literature on deliberation has an optimistic flavour, the literature on social choice is more mixed. It is centred around several paradoxes and impossibility results showing that collective decision making cannot generally satisfy certain plausible desiderata. Any democratic aggregation rule that we use in practice seems, at best, a compromise. Initially, the two literatures were largely disconnected from each other. Since the 1990s, however, there has been a growing dialogue between them (e.g., Miller 1992; Knight and Johnson 1994; van Mill 1996; Dryzek and List 2003; Landa and Meirowitz 2009). This chapter reviews the connections between the two. Deliberative democratic theory is relevant to social choice theory in that deliberation can complement aggregation and open up an escape route from some of its negative results. -

Kenneth Arrow's Contributions to Social

Kenneth Arrow’s Contributions to Social Choice Theory Eric Maskin Harvard University and Higher School of Economics Kenneth Arrow created the modern field of social choice theory, the study of how society should make collection decisions on the basis of individuals’ preferences. There had been scattered contributions to this field before Arrow, going back (at least) to Jean-Charles Borda (1781) and the Marquis de Condorcet (1785). But earlier writers all focused on elections and voting, more specifically on the properties of particular voting rules (I am ignoring here the large literature on utilitarianism – following Jeremy Bentham 1789 – which I touch on below). Arrow’s approach, by contrast, encompassed not only all possible voting rules (with some qualifications, discussed below) but also the issue of aggregating individuals’ preferences or welfares, more generally. Arrow’s first social choice paper was “A Difficulty in the Concept of Social Welfare” (Arrow 1950), which he then expanded into the celebrated monograph Social Choice and Individual Values (Arrow 1951). In his formulation, there is a society consisting of n individuals, indexed in1,..., , and a set of social alternatives A (the different possible options from which society must choose). The interpretation of this set-up depends on the context. For example, imagine a town that is considering whether or not to build a bridge across the local river. Here, “society” comprises the citizens of the town, and A consists of two options: “build the bridge” or “don’t build it.” In the case of pure distribution, where there is, say, a jug of milk and a plate of cookies to be divided among a group of children, the children are the society and A 1 includes the different ways the milk and cookies could be allocated to them. -

Computer-Aided Methods for Social Choice Theory

CHAPTER 13 Computer-aided Methods for Social Choice Theory Christian Geist and Dominik Peters 13.1 Introduction The Four Color Theorem is a famous early example of a mathematical result that was proven with the help of computers. Recent advances in artificial intelligence, particularly in constraint solving, promise the possibility of significantly extending the range of theorems that could be provable with the help of computers. Examples of results of this type are a special case of the Erdos˝ Discrepancy Conjecture (Konev and Lisitsa, 2014), and a solution to the Boolean Pythagorean Triples Problem (Heule et al., 2016). The proofs obtained in these two cases are only available in a computer-checkable format, and have sizes of 13 GB and 200 TB, respectively. Proofs like these do not have any hope of being human-checkable, and make the controversy about the proof of the Four Color Theorem pale in comparison. The computer-found proofs of results we discuss in this chapter, on the other hand, will have the striking property of being translatable to a human-readable version. Social choice theory studies group decision making, where the preferences of several agents need to be aggregated into one joint decision. This field of study has three characteristics that suggest applying computer-aided reasoning to it: it uses the axiomatic method, it is concerned with combinatorial structures, and its main concepts can be defined based on rather elementary mathematical notions. Thus, Nipkow (2009) notes that “social choice theory turns out to be perfectly suitable for mechanical theorem proving.” In this chapter, we will present a set of tools and methods first employed in papers by Tang and Lin (2009) and Geist and Endriss (2011) that, thanks to the aforementioned properties, will allow us to use computers to prove one of social choice theory’s most celebrated type of result: impossibility theorems. -

Publics and Markets. What's Wrong with Neoliberalism?

12 Publics and Markets. What’s Wrong with Neoliberalism? Clive Barnett THEORIZING NEOLIBERALISM AS A egoists, despite much evidence that they POLITICAL PROJECT don’t. Critics of neoliberalism tend to assume that increasingly people do act like this, but Neoliberalism has become a key object of they think that they ought not to. For critics, analysis in human geography in the last this is what’s wrong with neoliberalism. And decade. Although the words ‘neoliberal’ and it is precisely this evaluation that suggests ‘neoliberalism’ have been around for a long that there is something wrong with how while, it is only since the end of the 1990s neoliberalism is theorized in critical human that they have taken on the aura of grand geography. theoretical terms. Neoliberalism emerges as In critical human geography, neoliberal- an object of conceptual and empirical reflec- ism refers in the first instance to a family tion in the process of restoring to view a of ideas associated with the revival of sense of political agency to processes previ- economic liberalism in the mid-twentieth ously dubbed globalization (Hay, 2002). century. This is taken to include the school of This chapter examines the way in which Austrian economics associated with Ludwig neoliberalism is conceptualized in human von Mises, Friedrich von Hayek and Joseph geography. It argues that, in theorizing Schumpeter, characterized by a strong com- neoliberalism as ‘a political project’, critical mitment to methodological individualism, an human geographers have ended up repro- antipathy towards centralized state planning, ducing the same problem that they ascribe commitment to principles of private property, to the ideas they take to be driving forces and a distinctive anti-rationalist epistemo- behind contemporary transformations: they logy; and the so-called Chicago School of reduce the social to a residual effect of more economists, also associated with Hayek but fundamental political-economic rationalities. -

School Research Day Booklet 2012

School of Mathematics, Statistics and Applied Mathematics Research Day 26th April 2012 Contents Programme 9.30-10.00 Tea and Coffee 10.00-10.15 Ray Ryan Opening Remarks 10.15-10.45 Graham Ellis Measuring Shape 10.45-11.15 Ashley Piggins An Introduction to Social Choice Theory 11.15-11.45 Tea and Coffee 11.45-12.15 Johnny Burns The Topology of Homogeneous Spaces 12.15-12.45 Milovan Krnjajic Bayesian Modelling and Inverse Problems 12.45-2.00 Lunch and Poster Session in Arts Millennium Building 2.00-2.30 Niall Madden Postprocessing of Finite Element Solutions to One-Dimensional Convection-Diffusion Problems 2.30-3.45 Blitz Session 3.50-5.00 Poster Session in Arts Millennium Building 5.00 Reception and Presentation of Poster Prizes in Staff Club, Quadrangle Research Day 2012: Introduction 1 1 Introduction Welcome to the annual Research Day of the School of Mathematics, Statistics and Applied Mathematics. Research in the School covers a broad range of areas in pure and applied mathematics, statistics, biostatistics and bioinformatics. There are close to 30 PhD students in the School, spread across all these areas. Among the funded research activities in the School are the De Brun´ Centre for Computational Algebra and the Galway wing of the BIO-SI centre for bioinformatics and biostatistics, both supported by SFI under the Mathematics Initiative. The latter is a collaboration with the School of Mathematics and Statistics in the University of Limerick. There are several other collaborative activities with UL in mathematical modelling and in statistics. During the past year, a new interdisciplinary activity was formally initiated. -

Rationality and Choice

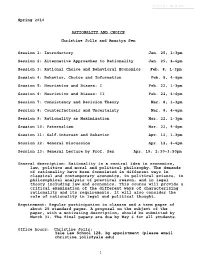

Spring 2010 RATIONALITY AND CHOICE Christine Jolls and Amartya Sen Session 1: Introductory Jan. 25, 1-3pm Session 2: Alternative Approaches to Rationality Jan. 25, 4-6pm Session 3: Rational Choice and Behavioral Economics Feb. 8, 1-3pm Session 4: Behavior, Choice and Information Feb. 8, 4-6pm Session 5: Heuristics and Biases: I Feb. 22, 1-3pm Session 6: Heuristics and Biases: II Feb. 22, 4-6pm Session 7: Consistency and Decision Theory Mar. 8, 1-3pm Session 8: Counterfactuals and Uncertainty Mar. 8, 4-6pm Session 9: Rationality as Maximization Mar. 22, 1-3pm Session 10: Paternalism Mar. 22, 4-6pm Session 11: Self-interest and Behavior Apr. 12, 1-3pm Session 12: General Discussion Apr. 12, 4-6pm Session 13: General Lecture by Prof. Sen Apr. 19, 2:30-3:50pm General description: Rationality is a central idea in economics, law, politics and moral and political philosophy. The demands of rationality have been formulated in different ways in classical and contemporary economics, in political science, in philosophical analysis of practical reason, and in legal theory including law and economics. This course will provide a critical examination of the different ways of characterizing rationality and its requirements. It will also consider the role of rationality in legal and political thought. Requirement: Regular participation in classes and a term paper of about 25 standard pages. A proposal on the subject of the paper, with a motivating description, should be submitted by March 31. The final papers are due by May 6 for all students. Office hours: Christine Jolls: Yale Law School 128, by appointment (please email [email protected]) 1 Amartya Sen: Mondays 11-12, Littauer Center 205, no appointment needed Tuesdays 11-12, Littauer Center 205, by appointment (please call 5-1871) General readings: The following books may be used as general reference: Richard Thaler, Quasi Rational Economics. -

Social Choice Theory and Adjudication Bruce Chapmant

The Rational and the Reasonable: Social Choice Theory and Adjudication Bruce Chapmant It is odd that the economic theory of rational choice has so little to say about the role of reasoning in rational decision mak- ing.' At a minimum, one would expect that the distinguishing fea- ture of rational choice would be that it involves reasoning. A choice without a reason seems arbitrary, the very opposite of what ra- tional choice would require. However, the rational choice theorist will likely reply that ra- tional choice involves reason in at least two respects. First, there is the idea of "dominance": a rational person should never (or does never) choose anything that she values less than other available alternatives. Second, there is "consistency": having already chosen in a particular way, a rational chooser should (or does)2 continue to t Associate Professor, Faculty of Law, University of Toronto. I wish to thank, without implicating, Ian Ayres, David Beatty, Alan Brudner, Jules Coleman, Dick Craswell, Ron Daniels, Dan Farber, Robert Howse, Lewis Kornhauser, Brian Langille, Richard Posner, Su- san Rose-Ackerman, David Schmidtz, Hamish Stewart, Cass Sunstein, Michael Trebilcock, George Triantis, Ernest Weinrib, and various participants at the second annual meeting of the American Law and Economics Association (Yale Law School, April 1992) for their com- ments on earlier versions of the arguments presented here. I am also very grateful to the Yale Law School for providing me with the opportunity to work on this Article by way of a 1991-92 Visiting Faculty Fellowship funded by the John M. Olin Foundation. -

Computational Social Choice: Theory and Applications

Report from Dagstuhl Seminar 15241 Computational Social Choice: Theory and Applications Edited by Britta Dorn1, Nicolas Maudet2, and Vincent Merlin3 1 Universität Tübingen, DE, [email protected] 2 UPMC – Paris, FR, [email protected] 3 Caen University, FR, [email protected] Abstract This report documents the program and the outcomes of Dagstuhl Seminar 15241 “Computational Social Choice: Theory and Applications”. The seminar featured a mixture of classic scientific talks (including three overview talks), open problem presentations, working group sessions, and five-minute contributions (“rump session”). While there were other seminars on related topics in the past, a special emphasis was put on practical applications in this edition. Seminar June 7–12, 2015 – http://www.dagstuhl.de/15241 1998 ACM Subject Classification I.2.11. Distributed Artificial Intelligence Keywords and phrases Computational Social Choice, Voting, Matching, Fair Division Digital Object Identifier 10.4230/DagRep.5.6.1 Edited in cooperation with Robert Bredereck 1 Executive Summary Britta Dorn Nicolas Maudet Vincent Merlin License Creative Commons BY 3.0 Unported license © Britta Dorn, Nicolas Maudet, and Vincent Merlin Computational social choice is an interdisciplinary research area dealing with the aggregation of preferences of groups of agents in order to reach a consensus decision that realizes some social objective. Economists typically view markets as an optimal mean for coordinating the activities and allocation of resources across a group of heterogeneous agents based on their utilities or preferences. By contrast, the methods of social choice, broadly defined, focus on coordination mechanisms that do not rely on prices, monetary/resource transfer or market structures, while still defining social objectives that account for individual preferences.